Essay/ Willem De Kooning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BLACK Baselitz, De Kooning, Mariscotti, Motherwell, Serra

Upsilon Gallery 404 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10018 [email protected] www.upsilongallery.com For immediate release BLACK Baselitz, de Kooning, Mariscotti, Motherwell, Serra April 13 – June 3, 2017 Curated by Marcelo Zimmler Spanish Elegy I, Lithograph, on brown HMP handmade paper, 13 3/4 x 30 7/8 in. (35 x 78.5 cm), 1975. Photo by Caius Filimon Upsilon Gallery is pleased to present Black, an exhibition of original and edition work by Georg BaselitZ, Willem de Kooning, Osvaldo Mariscotti, Robert Motherwell and Richard Serra, on view at 146 West 57 Street in New York. Curated by Marcelo Zimmler, the exhibition explores the role played by the color black in Post-war and Contemporary work. In the 1960s, Georg BaselitZ emerged as a pioneer of German Neo–Expressionist painting. His work evokes disquieting subjects rendered feverishly as a means of confronting the realities of the modern age, and explores what it is to be German and a German artist in a postwar world. In the late 1970s his iconic “upside-down” paintings, in which bodies, landscapes, and buildings are inverted within the picture plane ignoring the realities of the physical world, make obvious the artifice of painting. Drawing upon a dynamic and myriad pool of influences, including art of the Mannerist period, African sculptures, and Soviet era illustration art, BaselitZ developed a distinct painting language. Upsilon Gallery 404 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10018 [email protected] www.upsilongallery.com Willem de Kooning was born on April 24, 1904, into a working class family in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. -

C100 Trip to Houston

Presented in partnership with: Trip Participants Doris and Alan Burgess Tad Freese and Brook Hartzell Bruce and Cheryl Kiddoo Wanda Kownacki Ann Marie Mix Evelyn Neely Yvonne and Mike Nevens Alyce and Mike Parsons Your Hosts San Jose Museum of Art: S. Sayre Batton, deputy director for curatorial affairs Susan Krane, Oshman Executive Director Kristin Bertrand, major gifts officer Art Horizons International: Leo Costello, art historian Lisa Hahn, president Hotel St. Regis Houston Hotel 1919 Briar Oaks Lane Houston, Texas, 77027 Phone: 713.840.7600 Houston Weather Forecast (as of 10.31.16) Wednesday, 11/2 Isolated Thunderstorms 85˚ high/72˚ low, 30% chance of rain, 71% humidity Thursday, 11/3 Partly Cloudy 86˚ high/69˚ low, 20% chance of rain, 70% humidity Friday, 11/4 Mostly Sunny 84˚ high/63 ˚ low, 10% chance of rain, 60% humidity Saturday, 11/5 Mostly Sunny 81˚ high/61˚ low, 0% chance of rain, 42% humidity Sunday, 11/6 Partly Cloudy 80˚ high/65˚ low, 10% chance of rain, 52% humidity Day One: Wednesday, November 2, 2016 Dress: Casual Independent arrival into George Bush Intercontinental/Houston Airport. Here in “Bayou City,” as the city is known, Houstonians take their art very seriously. The city boasts a large and exciting collection of public art that includes works by Alexander Calder, Jean Dubuffet, Michael Heizer, Joan Miró, Henry Moore, Louise Nevelson, Barnett Newman, Claes Oldenburg, Albert Paley, and Tony Rosenthal. Airport to hotel transportation: The St. Regis Houston Hotel offers a contracted town car service for airport pickup for $120 that would be billed directly to your hotel room. -

Washington University Record, July 2, 1987

Washington University School of Medicine Digital Commons@Becker Washington University Record Washington University Publications 7-2-1987 Washington University Record, July 2, 1987 Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/record Recommended Citation "Washington University Record, July 2, 1987" (1987). Washington University Record. Book 414. http://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/record/414 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington University Publications at Digital Commons@Becker. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Record by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Becker. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I '/^OH/MGr / O/N/ /V//i/5/7V ,~*:-- § Washington WASHINGTON ■ UNIVERSITY- IN • ST- LOUIS ARCHIVES u*«ry JUL i '87 RECORD Vol. 11 No. 36/July 2, 1987 Science academy's medical institute elects two faculty Two faculty members at the School of Medicine have been elected mem- bers of the prestigious Institute of Medicine of the National Academy of Sciences. New members of the institute are Michel M. Ter-Pogossian, Ph.D., and Samuel A. Wells Jr., M.D. Ter- Pogossian is professor of radiology at the School of Medicine and director of radiation sciences for Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology. Wells is Bixby Professor and chairman of the De- partment of Surgery at the medical school. He is also chief of surgery at Barnes and Children's Hospitals in the Washington University Medical Center. The two are among 40 new members elected to the institute in recognition of their contributions to health and medicine or related fields. As members of the institute, which was established in 1970, Wells and Ter-Pogossian will help examine health policy issues and advise the federal government. -

Art in 1960S

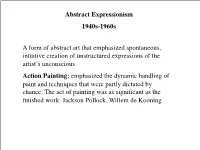

Abstract Expressionism 1940s-1960s A form of abstract art that emphasized spontaneous, intuitive creation of unstructured expressions of the artist’s unconscious Action Painting: emphasized the dynamic handling of paint and techniques that were partly dictated by chance. The act of painting was as significant as the finished work: Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning Jackson Pollock, Blue Poles, 1952 William de Kooning, Untitled, 1975 Color-Field Painting: used large, soft-edged fields of flat color: Mark Rothko, Ab Reinhardt Mark Rothko, Lot 24, “No. 15,” 1952 “A square (neutral, shapeless) canvas, five feet wide, five feet high…a pure, abstract, non- objective, timeless, spaceless, changeless, relationless, disinterested painting -- an object that is self conscious (no unconsciousness), ideal, transcendent, aware of no thing but art (absolutely no anti-art). Ad Reinhardt, Abstract Painting,1963 –Ad Reinhardt Minimalism 1960s rejected emotion of action painters sought escape from subjective experience downplayed spiritual or psychological aspects of art focused on materiality of art object used reductive forms and hard edges to limit interpretation tried to create neutral art-as-art Frank Stella rejected any meaning apart from the surface of the painting, what he called the “reality effect.” Frank Stella, Sunset Beach, Sketch, 1967 Frank Stella, Marrakech, 1964 “What you see is what you see” -- Frank Stella Postminimalism Some artists who extended or reacted against minimalism: used “poor” materials such felt or latex emphasized process and concept rather than product relied on chance created art that seemed formless used gravity to shape art created works that invaded surroundings Robert Morris, Felt, 1967 Richard Serra, Cutting Device: Base Plat Measure, 1969 Hang Up (1966) “It was the first time my idea of absurdity or extreme feeling came through. -

Retrospective Is Curated by Toby Kamps with Dr

Wols: Retrospective is curated by Toby Kamps with Dr. Ewald Rathke. This exhibition is generously supported by the National Endowment for the Arts; Anne and Bill Stewart; Louisa Stude Sarofim; Michael Born Alfred Otto Wolfgang Schulze to a prominent Berlin family Zilkha; Skadden, Arps; and the City of Houston. on May 27, 1913, the artist spent his childhood in Dresden. Despite obvious intelligence, Wols failed to complete school, and in 1932, not long after the death of his father, with whom he had a contentious relationship, he moved to Paris in an attempt to break away from his bourgeois roots. Except for a brief stint in Spain, he remained in France until his untimely death in 1951. The story of Wols’s dramatic trans- PUBLIC PROGRAMS formation from sensitive, musically gifted German youth to eccentric, Panel Discussion near-homeless Parisian artist is legendary. So too are accounts of his Thursday, September 12, 2013, 6:00 p.m. many adventures and misadventures during the tumult of wartime Following introductory remarks by Frankfurt-based scholar Dr. Ewald Europe: his marriage to the fiercely protective Romanian hat maker Rathke, Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art Toby Kamps is joined Gréty Dabija; his grueling incarceration as an expatriate at the outset by art historians Patrycja de Bieberstein Ilgner, Archivist at the Karin and of the war and subsequent moves across rural France; his late-night Uwe Hollweg Foundation, Bremen, Germany; and Katy Siegel, Professor perambulations in liberated Paris; and his ever-worsening alcoholism, of Art History at Hunter College, New York, and Chief Curator of the Wols, Selbstporträt (Self-Portrait), 1937 or 1938, modern print. -

Hartford, Connecticut R EPORT

W ADSWORTH A THENEUM M USEUM OF A RT 2009 A NNUAL R EPORT Hartford, Connecticut R EPORT from the President In 1932, in the midst of the Great Depression, A Everett Austin, Jr. opined that All tenses of time conjoin at the Wadsworth Atheneum, an institution “…the appreciation of works of art serves…to allay for some moments the which continuously honors its historic past, while living in the present and worry and anxiety in which we all share.” It is uplifting to know that over the planning for the future. As we continue to devise both short and long term strate - past twelve months, when the world experienced a challenging financial collapse, gies to preserve our financial stability and enhance the museum’s position as a the gravity of which has not been witnessed since the 1930s, the Wadsworth cultural leader both locally and internationally, we remain fully committed to Atheneum continued as a thriving and stable institution, ensuring that the the constituents who help make our visions a reality through their unwavering lega cy we leave to future generations will be a strong one. support. At the outset of the crisis, the museum implemented swift budgetary To all of the members, friends, patrons, and devotees of this museum— measures in a determined effort to reduce costs. Despite these difficult meas - you have my sincere gratitude. I encourage you to maintain your vital support ures, we remained committed to our artistic mission and to upholding the trust —particularly now, as institutions like ours play a critical role as a place of per - placed in us by our community. -

Minimalism & Beyond

MINIMALISM & BEYOND MINIMALISM & BEYOND MNUCHIN GALLERY ACKNOWLEDGMENTS CONTENTS Mnuchin Gallery is proud to present Minimalism & Beyond. The gallery has a long history of A MINIMAL LEGACY exhibiting some of the finest examples of Minimalist art, including the world’s first-ever exhibition of Donald Judd stacks in 2013, and the group exhibition Carl Andre in His Time PAC POBRIC in 2015. For over 25 years, we have been privileged to live alongside works by many of the artists in this show, including Agnes Martin, Robert Ryman, and Frank Stella, in addition 7 to Judd and Andre. Over this time, we have noted the powerful impact these works have had on the generations of artists who followed, and the profound resonances between these landmark works from the 1960s and some of the best examples of the art of today. Now, in this exhibition, we are delighted to bring together these historic works alongside painting and sculpture spanning the following five decades, many by artists being shown WORKS at the gallery for the first time. This exhibition would not have been possible without the collaborative efforts of the 21 Mnuchin team, especially Michael McGinnis. We are grateful to the generous private collections that have entrusted us with their works and allowed us to share them with the public. We thank our catalogue author, Pac Pobric, for his engaging and insightful essay. We commend McCall Associates for their catalogue design. And we thank our Exhibitions EXHIBITION CHECKLIST Director, Liana Gorman, for her thoughtful and thorough contributions. 79 ROBERT MNUCHIN SUKANYA RAJARATNAM MICHAEL MCGINNIS 7 A MINIMAL LEGACY PAC POBRIC In the photograph, Donald Judd looks appreciative, but vaguely apprehensive. -

The Ceramic Presence in Modern Art: Selections from the Linda Leonard Schlenger Collection and the Yale University Art Gallery September 4, 2015–January 3, 2016

YA L E U N I V E R S I T Y A R T PRESS For Immediate Release GALLERY RELEASE August 12, 2015 EXHIBITION RE-EXAMINES THE ROLE THAT CLAY HAS PLAYED IN ART MAKING DURING THE SECOND HALF OF THE 20TH CENTURY The Ceramic Presence in Modern Art: Selections from the Linda Leonard Schlenger Collection and the Yale University Art Gallery September 4, 2015–January 3, 2016 August 12, 2015, New Haven, Conn.—Over the last 25 years, Linda Leonard Schlenger has amassed one of the most important collec- tions of contemporary ceramics in the country. The Ceramic Presence in Modern Art features more than 80 carefully selected objects from the Schlenger collection by leading 20th-century artists who have engaged clay as an expressive medium—including Robert Arneson, Hans Coper, Ruth Duckworth, John Mason, Kenneth Price, Lucie Rie, and Peter Voulkos—alongside a broad array of artworks created in clay and other media from the Yale University Art Gallery’s perma- nent collection. Although critically lauded within the studio-craft movement, many ceramic pieces by artists who have continuously or periodically worked in clay are only now coming to be recognized as important John Mason, X-Pot, 1958. Glazed stoneware. Linda Leonard Schlenger Collection. © John Mason and integral contributions to the broader history of modern and contemporary art. By juxtaposing exceptional examples of ceramics with great paintings, sculptures, and works on paper and highlighting the formal, historical, and theoreti- cal affinities among the works on view, this exhibition aims to re-examine the contributions of ceramic artists to 20th- and 21st-century art. -

A Study of the Painting Styles of Willem De Kooning and Larry Rivers and Their Influence on My Own Orkw

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Plan B Papers Student Theses & Publications 1-1-1967 A Study of the Painting Styles of Willem De Kooning and Larry Rivers and their Influence on my Own orkW Paula J. Reinhard Follow this and additional works at: https://thekeep.eiu.edu/plan_b Recommended Citation Reinhard, Paula J., "A Study of the Painting Styles of Willem De Kooning and Larry Rivers and their Influence on my Own ork"W (1967). Plan B Papers. 539. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/plan_b/539 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Plan B Papers by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. - A STUDY o~ THE PAINTING STYLES OF WILLEM DE KOONING AND LARRY RIVERS AND THEIR INFLUENCE ON MY OWN WORK (TITLE) BY PAULA J. REINHARD PLAN B PAPER SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF SCIENCE IN EDUCATION AND PREPARED IN COURSE ART 570 IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL, EASTERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY, CHARLESTON, ILLINOIS 1967 YEAR I HEREBY RECOMMEND THIS PLAN B PAPER BE ACCEPTED AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE DEGREE, M.S. IN ED. ~ ADVISER DEPARTMENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements • • • • • • • • • • • ii Table of Contents • • • • . .. List of Illustrations • • • • • • • • • j v Introduction •••••••••••••• 1 Chapter I William De Koon~ng ••••••••••• 1 II Larry Rivers •••• . .. • ,g ITI Comparison of the Stvle of Poth Artists, and the Changes in My own Paint1n~ • • • • • • • • • • • . 1~ IV Conclusion •• . 1g Bibliograrhv • • • • • • • • . 2? iii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Plate I. -

Robert Motherwell and Harvard with the Intention of Becoming a Philosopher

Motherwell was born in Aberdeen, Washington and studied at Stanford Robert Motherwell and Harvard with the intention of becoming a philosopher. He was in- Artist ( 1915 – 1991 ) fluenced by Alfred North Whitehead, who first challenged him with the notion of abstraction, and when Motherwell moved to New York in 1940 he took that sensibility with him. Motherwell lived in Greenwich Village where he joined a group of art- ists—including Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko and Franz Kline—who set out to change the face of American painting. These artists renounced the prevalent American style, believing its real- ism depicted only the surface of American life. Influenced by the Sur- realists, many of whom had emigrated from Europe to New York, the Abstract Expressionists sought to create essential images that revealed emotional truth and authenticity of feeling. These early years were an incredibly productive period for Motherwell and he experimented in a range of media, from painting to printmak- ing to collage. His work often expressed the actions of the artist through dramatic and bright brush strokes. Valued for their energetic imagery, they attempted a pure emotional response made real in paint. Beyond his individual efforts as an artist, Motherwell played a major role in the intellectual and artistic development of the underground New York art world. A serious art historian, Motherwell founded the Documents of Art series. Reflecting on those early years, he spoke of their belief that “if the ab- straction, the violence, the humanity was valid in Abstract Expression- ism, then it cut out the ground from every other kind of painting.” With the advent of Pop Art and its concentration on popular culture themes, the art public began to long for the idealism of the Abstract Expression- ists. -

Minimalism 1 Minimalism

Minimalism 1 Minimalism Minimalism describes movements in various forms of art and design, especially visual art and music, where the work is stripped down to its most fundamental features. As a specific movement in the arts it is identified with developments in post–World War II Western Art, most strongly with American visual arts in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Prominent artists associated with this movement include Donald Judd, John McLaughlin, Agnes Martin, Dan Flavin, Robert Morris, Anne Truitt, and Frank Stella. It is rooted in the reductive aspects of Modernism, and is often interpreted as a reaction against Abstract expressionism and a bridge to Postmodern art practices. The terms have expanded to encompass a movement in music which features repetition and iteration, as in the compositions of La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, Philip Glass, and John Adams. Minimalist compositions are sometimes known as systems music. (See also Postminimalism). The term "minimalist" is often applied colloquially to designate anything which is spare or stripped to its essentials. It has also been used to describe the plays and novels of Samuel Beckett, the films of Robert Bresson, the stories of Raymond Carver, and even the automobile designs of Colin Chapman. The word was first used in English in the early 20th century to describe the Mensheviks.[1] Minimalist design The term minimalism is also used to describe a trend in design and architecture where in the subject is reduced to its necessary elements. Minimalist design has been highly influenced by Japanese traditional design and architecture. In addition, the work of De Stijl artists is a major source of reference for this kind of work. -

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum Teacher Resource Unit

MAY 24, 2019–JANUARY 12, 2020 Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum Teacher Resource Unit Artistic License: Six Takes on the Guggenheim Collection, the first artist-curated exhibition mounted at the Guggenheim, occupies the entire rotunda and celebrates the museum’s extensive holdings of twentieth-century modern and contemporary art. Curated by six contemporary artists who each have helped to shape the Guggenheim’s history with their own pivotal solo shows—Cai Guo-Qiang, Paul Chan, Jenny Holzer, Julie Mehretu, Richard Prince, and Carrie Mae Weems—the presentation brings together collection highlights and rarely seen works from the turn of the century to 1980. Artistic License features nearly three hundred paintings, sculptures, works on paper, and installations, some never before exhibited, that engage with the cultural discourses of their time—from the utopian aspirations of early modernism to the formal explorations of mid-century abstraction to the sociopolitical debates of the 1960s and ’70s. On view during the sixtieth anniversary of the Guggenheim’s iconic Frank Lloyd Wright–designed building, the exhibition honors the museum’s artist-centric ethos, furthers its commitment to art as a force for upending expectations and expanding perspectives, and offers a critical examination of its collection. Artistic License: Six Takes on the Guggenheim Collection is made possible by Major support is provided by Support is also provided by The Kate Cassidy Foundation. The Leadership Committee for Artistic License: Six Takes on the Guggenheim Collection is gratefully acknowledged for its support, with special thanks to Stefan Edlis and Gael Neeson; Larry Gagosian; Fundación Almine y Bernard Ruiz-Picasso para el Arte; Marian Goodman Gallery; Nahmad Contemporary; Peter Bentley Brandt; Hauser & Wirth; Allison and Neil Rubler; and those who wish to remain anonymous.