Understanding the Process and Complex Dynamics of Mutual Aid

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

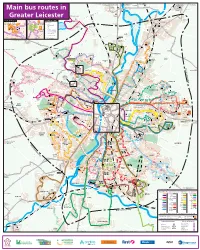

Main Bus Services Around Leicester

126 to Coalville via Loughborough 27 to Skylink to Loughborough, 2 to Loughborough 5.5A.X5 to X5 to 5 (occasional) 127 to Shepshed Loughborough East Midlands Airport Cossington Melton Mowbray Melton Mowbray and Derby 5A 5 SYSTON ROAD 27 X5 STON ROAD 5 Rothley 27 SY East 2 2 27 Goscote X5 (occasional) E 5 Main bus routes in TE N S GA LA AS OD 126 -P WO DS BY 5A HALLFIEL 2 127 N STO X5 SY WESTFIELD LANE 2 Y Rothley A W 126.127 5 154 to Loughborough E S AD Skylink S 27 O O R F N Greater Leicester some TIO journeys STA 5 154 Queniborough Beaumont Centre D Glenfield Hospital ATE RO OA BRA BRADG AD R DGATE ROAD N Stop Services SYSTON TO Routes 14A, 40 and UHL EL 5 Leicester Leys D M A AY H O 2.126.127 W IG 27 5A D H stop outside the Hospital A 14A R 154 E L A B 100 Leisure Centre E LE S X5 I O N C Skylink G TR E R E O S E A 40 to Glenfield I T T Cropston T E A R S ST Y-PAS H B G UHL Y Reservoir G N B Cropston R ER A Syston O Thurcaston U T S W R A E D O W D A F R Y U R O O E E 100 R Glenfield A T C B 25 S S B E T IC WA S H N W LE LI P O H R Y G OA F D B U 100 K Hospital AD D E Beaumont 154 O R C 74, 154 to Leicester O A H R R D L 100 B F E T OR I N RD. -

Trades. Boo ~')31

. RUTLAND.) A~D TRADES. BOO ~')31- Garner J. &; Sons Limited, 89 &; gr 'Runt Thomas George, •Premier 1 Ney Bros. Hill st. Barwell, Hinckley Crafton street, Leicester works, Melton road, Leicester & Nichols, Son & Clo-, 5o & 52 Garner &; Partridge, II3 to II7 Wil- Roth!ey, Leicester Norl:hgate atreet, Leicester low street, Leicester Burst, Cotton & Ropcroft, 25 Station Nixon Henry & Co.Victoria rd. north, Garner, White & Breward, Stapleton road, Earl Sbilton, Rinckley Belgrave, Leicester lane. Barwell, Hinckley Ideal Boot Co-operative Society Ltd. Nixon Geo. 39 Vauxhall st. Leicester Garner &; Co. Queen street, Barwell, (Alfred Pegg, sec.), 3 Southgate North Evington Boot Co.Stone Bridge Hinckley street, Leicester street; 2 Southdown road & Vie- Garner A. Mountsorrel, Loughboro' Jarvis F. & Co. Trinity la. Rinckley toria road east, West Rurnberstone, Garner Daniel, 40 Lothair road, J ennings E. & Co. Ltd. 74 Church Leicester Aylestone park, Leicester gate, Leicester Olin Bros. Spittlehouse st. Leicester Geary Bros. Stapleton lane, Barwell, J enninge W. A. So Moores road, Bel- Orton H. & Sons, 2 Oxford st. Earl Hinckley grave, Leicester Shilton, Hinckley Geary & Hall, High st.Barwe!l,Hnckly J ewsbury Seth, I04! .Wheat st.Lcstr Padmore & Barnes Ltd. rr De Mont Glentield Progress Co-operative Soc. Johnson J. & Co. Ash street, West fort chmbrs. Rorsefair st. LeicestH Lim. (J. H. Brewin, manager),Glen- Hnmberstone, Leicester Page & Potter, :a, & 4 King's Newton field, Leicester Johnson W. & Co. (Hmckley) Ltd. street, Leicester Glover J. & E. ID Lichfie!d street & Upper Bond street, Rinckley Palfreyman F. J. & Oo. Dorotby rd. Cra.ne Street, Leicester Jones & Gamble, 34! H1ghcross st. -

List of Polling Stations for Leicester City

List of Polling Stations for Leicester City Turnout Turnout City & Proposed 2 Polling Parliamentary Mayoral Election Ward & Electorate development Stations Election 2017 2019 Acting Returning Officer's Polling Polling Place Address as at 1st with potential at this Number comments District July 2019 Number of % % additional location of Voters turnout turnout electorate Voters Abbey - 3 member Ward Propose existing Polling District & ABA The Tudor Centre, Holderness Road, LE4 2JU 1,842 750 49.67 328 19.43 Polling Place remains unchanged Propose existing Polling District & ABB The Corner Club, Border Drive, LE4 2JD 1,052 422 49.88 168 17.43 Polling Place remains unchanged Propose existing Polling District & ABC Stocking Farm Community Centre, Entrances From Packwood Road And Marwood Road, LE4 2ED 2,342 880 50.55 419 20.37 Polling Place remains unchanged Propose existing Polling District & ABD Community of Christ, 330 Abbey Lane, LE4 2AB 1,817 762 52.01 350 21.41 Polling Place remains unchanged Propose existing Polling District & ABE St. Patrick`s Parish Centre, Beaumont Leys Lane, LE4 2BD 2 stations 3,647 1,751 65.68 869 28.98 Polling Place remains unchanged Whilst the Polling Station is adequate, ABF All Saints Church, Highcross Street, LE1 4PH 846 302 55.41 122 15.76 we would welcome suggestions for alternative suitable premises. Propose existing Polling District & ABG Little Grasshoppers Nursery, Avebury Avenue, LE4 0FQ 2,411 1,139 66.61 555 27.01 Polling Place remains unchanged Totals 13,957 6,006 57.29 2,811 23.09 Aylestone - 2 member Ward AYA The Cricketers Public House, 1 Grace Road, LE2 8AD 2,221 987 54.86 438 22.07 The use of the Cricketers Public House is not ideal. -

Leicester (Haymarket Bus Station)

Leicester Station i Onward Travel Information Buses and Taxis Local area map Leicester is a PlusBus area Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2018 & also map data © OpenStreetMap contributors, CC BY-SA PlusBus is a discount price ‘bus pass’ that you buy with Rail replacement buses and coaches depart from the front of the station. your train ticket. It gives you unlimited bus travel around your chosen town, on participating buses. Visit www.plusbus.info Main destinations by bus (Data correct at July 2019) DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP { Aylestone / Aylestone Park 48, 48A ED UHL(Mon-Fri) ED U2/U3 { Beaumont Centre 54, 54A EG { Leicester General Hospital 54A (Eves) EF Oadby Student Village (John (University { ED 22, 22A, 22B, 16 EC Foster Hall) term time { Belgrave EG 54 15 minutes walk from this only) { Birstall 22A, 22B EG station (see local area map) { Oadby (Town Centre/The Parade) 31, 31A EE see Leicester City Centre Leicester (Haymarket Bus 22, 22A, 31, { Rushey Mead 22 EG { City Centre { below Station) 31A, 44, 44A, { South Evington (Highway Road) 81 EF EG and EH 48, 48A, 80 47, 47A, 54, { Stoneygate (London Road) 31, 31A EE (University 54A, X7 31, 31A (alight { Clarendon Park ED term time 10 minutes walk from this bus at Glebe EE only) Leicester HM Prison station (see local area map) Road) University of Leicester Botanic 48, 48A, U2/ UHL(Mon-Fri) A { U2/U3 Gardens U3 (University X3, U2/U3 (University { De Montfort Hall ED ED term time -

Leicester Primitive Methodism by Rev Arthur Jubb on Sunday March 1St 1818 Primitive Methodism Made Its First Appeal to Leidester

From the Handbook of the 108th Annual Primitive Methodist Conference held in Leicester in 1927 Leicester Primitive Methodism by Rev Arthur Jubb On Sunday March 1st 1818 Primitive Methodism made its first appeal to Leidester. On that day a big crowd assembled at the Cross, Belgrave Gate. John Benton, a powerful open-air speaker, preached from the words: “Let me die the death of the righteous and let my last end be like his.” Amongst those then waon to Christ was one William Goodrich who afterwards rendered distinguished service. From that March day, progress was rapid and sure. William CLowes, the chief apostle of Primitive Methodism, after a tiring day in the villages, arrived in Leicester on a Sunday evening. The next morning John Wedgewood and he preached to a crowd of two thousand people in Belgrave Gate.. Their texts were Job 22:21 and Revelation 3:20. The service was orderly the people as reverent as if in church. There followed that afternoon a four and a half hours’ prayer meeting in a house in Orchard Street. Like another house in Galilee long ago whe Jesus was the Magnet, this house was crowded to the door; many stood outside listening to the prayers and exhortations and songs of those within. Twenty people then surrendered themselves to Christ. The results of those first meetings were notable. Men and women of marked individuality were consecrated to its extension. A small chapel in Millstone Lane was rented and used for some months as a meeting place, but by Christmas Day 1819 a chapel had been built in George Street. -

Spinney Hill Factory Trail

A Factory Trail from Spinney Hill Park Start location: Outside the café in Spinney Hill Park, off East Park Road, Leicester. Time taken: 50 minutes (approximately)* Distance: 1.7 miles 2.8 km Circular route Description: This walk passes some former factory buildings from the late 19th century to mid-20th century in the area around Spinney Hill Park. Learn a little about the companies that were based here and what they produced during Leicester's manufacturing past. Data CC-By-SA by OpenStreetMap www.openstreetmap.org/copyright Created in QGIS-CC-0 Main route Stage / waypoint A Point of interest *Time is calculated at a steady pace of 2mph This route was developed by staff and volunteers for Leicester City Council: www.choosehowyoumove.co.uk/walks Walk starts at: Outside the café in Spinney Hill Park, off East Park Road, Leicester. Route directions: 1. From the noticeboard by the cafe, head towards the path junction at the centre of the park. Turn right on the main path. At the path junction before the sports courts bear left, then turn right before the park lodge to exit on St Saviour's Road. Turn right along St Saviour’s Road. Soon, cross over to the opposite side by the small traffic island. 2. Turn left into Asfordby Street and continue ahead, passing the attractive mosque to your right. Pause at Atkinson Street. On the corner of Asfordby Street / Atkinson Street in the former Anchor Boot Works (A). Continue on Asfordby Street and turn left on Wood Hill. The building on your left before the steps is the former Vauxhall Works (B). -

Main Bus Routes in Central Leicestershire

126 to Coalville via Loughborough 27.X27 to Skylink to Loughborough, 2 to Loughborough 128 to Melton Mowbray 5 5.5A to 127 to Shepshed Loughborough East Midlands Airport Cossington Melton Mowbray and Derby ROAD OAD SYSTON East SYSTON R 128 Rothley 27 Goscote 2 27 27 E 5 Main bus routes in TE N S 5A GA LA S OD -PA WO S BY HALLFIELD 5 N STO SY WESTFIELD LANE 126 127 Y A Rothley W 27 5 E S 128 AD S Queniborough O O R F N Central Leicestershire TIO STA 5 54.123 to Loughborough ATE ROA BRADG D 2 D Glenfield Hospital Beaumont OA BRAD R GATE ROAD 126.127 N SYSTON TO Centre EL 5 Leicester Leys D Skylink M A O 54 WAY 6 5A R D Y BE L X27 A LE 27 Leisure Centre E G A Stop Services N IC 123 O O E R H 128 1 TI ST IG W H A E T R S Y-PASS S H T 7 Cropston Reservoir B R 1 not in use E G E 2 Cropston R ERN 6 T O Thurcaston U T H S R A E D O W D T A 6 R Y I U R A O 2 14A, 40, 302 O E R Glenfield T W R 3 S B E 6 T C W I AN F H E LI Leicester Road L P E S R Y H G O AD S N UHL D B O U 2 A 100 K Hospital F 4 E Beaumont 54 O R E 123 O R A B R 55 L L D FOR RD. -

Community Watch

WATCH WORD For Leicester & Leicestershire Newsletter of CITY & COUNTY NEIGHBOURHOOD WATCH – (LEICESTER & LEICESTERSHIRE) Working in SUPPORT of LEICESTERSHIRE POLICE. Charity No. 1072275 Issue 34/2016 The City & County Neighbourhood Watch is here to represent the concerns of members and their families. We operate entirely outside the police chain of command, so we can always promise an independent and confidential service Working in SUPPORT of LEICESTERSHIRE POLICE SAVE THE DATE! - THURSDAY 15TH SEPTEMBER 2016 - 7.30pm CITY & COUNTY NEIGHBOURHOOD WATCH MEMBERS YEARLY MEETING ST THOMAS MORE CHURCH HALL, Knighton Road, Leicester, LE2 3TT Guest Presenter will Be: Debbie Gardner – Relationship Coordinator – Severn Trent Water – supported by Leicestershire Police TOPIC: BOGUS CALLERS / DISTRACTION BURGLARS LEICESTERSHIRE POLICE Kayleigh’s Love Story shortlisted for national award Download high resolution image Issued on 26/8/16 at 2:17 p.m. A five minute film produced by Leicestershire Police highlighting the dangers of online grooming has been shortlisted for a prestigious national award. Kayleigh’s Love Story is one of the finalists in the Social Screen category of the Clarion Awards run by EVCOM – the so-called Oscars of the specialist video produced by the corporate and charity sectors. The film tells the story of aspects of the last two weeks in the life of Measham Schoolgirl Kayleigh Haywood who was groomed online over 13 days by Ibstock resident Luke Harlow. She eventually agreed to spend the evening at his house, and two days later she was raped and murdered by his next door neighbour, Stephen Beadman. The film has been made to raise greater awareness amongst children and parents of grooming and child sexual abuse and exploitation. -

Foia 8547 Attachment 1.Pdf

Name of Organisation/Project 2015/16 2014/15 2013/14 2012/13 Ward 5 Communities Project (SDSA Leicester) 14,070 City wide A4e Management Ltd 370,700 Castle Ace Project (Voluntary Action Leicester) 15,998 City wide Action Deafness Ltd 8,655 Belgrave Adhar 63,546 63,546 63,546 Stoneygate Adhar (Recommission Service) 4,150 Stoneygate Adhar (Serving 3 Communities) Asian (N&E) & African Com 90,789 Stoneygate Adventure Play Buildings 496 2,422 4,224 2,318 Various (Adventure Playgrounds) Advance Housing 53,154 54,054 City Wide African Caribbean Centre Development Group 3,477 11,837 Wycliffe African Caribbean Citzn Forum 32,325 43,100 43,100 43,100 City Wide Age UK Leicester Shire & Contract Care Ltd 613,408 997,824 1,011,492 Castle Age UK Leicester Shire & Rutland 145,274 103,449 Castle Ajani Women & Girls Centre Ltd 68,637 Stoneygate Akwaaba 99,558 90,041 Stoneygate Allexton Youth & Comm. Centre 10,556 14,778 Braunstone Pk & Rowley Fields Alzheimers Society 40,899 51,136 51,136 51,136 Citywide Angels & Monsters (Summer Playschemes) 3,400 4,760 Braunstone Pk & Rowley Fields Ansaar 13,300 53,746 49,453 49,453 Spinney Hills Asian Tower Club 947 2,256 2,444 2,253 Belgrave Baby Gear 30,096 72,930 72,930 Castle Bal Nagri 3,600 Belgrave/Rushey Mead Bangladesh Youth & Cultural Shomiti (Carers Respite) 14,382 14,382 Stoneygate Bangladesh Youth & Cultural Shomiti (Supplementary Learning Project) 7,834 31,610 Stoneygate Bangladeshi Language School 14,000 Wycliffe Barnardo´s 44,260 80,723 66,421 130,494 City wide Beaumont Lodge Neighbourhood Association 3,167 9,500 9,500 9,500 Beaumont Leys Belgrave Neighbourhood Lunch Club 9,601 9,601 9,601 9,601 Belgrave Belgrave Playgroup 15,663 15,663 Belgrave/Rushey Mead Belgrave Playhouse 45,533 75,324 143,025 152,503 Belgrave/Rushey Mead Belgrave Playhouse Playgroup 9,777 10,206 Belgrave/Rushey Mead Braunstone Adventure Playground 58,489 101,517 116,978 119,414 Braunstone Pk & Rowley Fields Braunstone Carnival 500 500 500 1,000 Braunstone Braunstone Frith Tenants Association 1,434 2,068 1,064 710 New Parks British Red Cross M.A.D. -

Leicester City

Funded by needs analysis summary report for early years leicester city DECEMBER 2019 © BETTER COMMUNICATION CIC, 2020 BC011 Needs_Analysis_Leicester_v3_JG.indd 1 07/09/2020 21:41 Introduction This report provides a high-level summary of the needs analysis in relation to speech, language and communication in the Early Years in Leicester as part of the Early Outcomes Fund Early Years project across Leicester, Nottingham and Derby Cities. Detailed data capture can be found in the Balanced System® Early Outcomes Fund account which can be accessed by Strategic and City Leads. BC011 Needs_Analysis_Leicester_v3_JG.indd 2 07/09/2020 21:41 THE BALANCED SYSTEM® BC011 Needs_Analysis_Leicester_v3_JG.indd 3 07/09/2020 21:41 The Balanced System® The methodology for the audit uses the Balanced System® Core Model (see diagram) and associated online tools to audit quantitative and qualitative data. Quantitative data includes an analysis at ward level of the population, demographic, predicted speech, language and communication needs along with demand in the form of referrals and caseload of children and young people known to the speech and language therapy service and the workforce to meet the identified need. Workforce and known caseload data, where this has been shared, are available at a City-wide level but is not readily available to triangulate at ward level. Educational attainment data and Ofsted data are also considered. This quantitative analysis is triangulated with qualitative information about the range of provisions and identified gaps in provision across the Five Strands of the Balanced System®: Family Support, Environment, Workforce, Identification and Intervention and across the three levels of universal, targeted and specialist support. -

54 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

54 bus time schedule & line map 54 Beaumont Centre - Goodwood View In Website Mode The 54 bus line (Beaumont Centre - Goodwood) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Beaumont Leys: 6:00 AM - 10:42 PM (2) Goodwood: 5:55 AM - 10:45 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 54 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 54 bus arriving. Direction: Beaumont Leys 54 bus Time Schedule 48 stops Beaumont Leys Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 8:55 AM - 9:40 PM Monday 6:00 AM - 10:42 PM Walshe Road, Goodwood Tuesday 6:00 AM - 10:42 PM Greenacre Drive, Crown Hills Thomasson Road, Leicester Wednesday 6:00 AM - 10:42 PM Rockingham Close, Crown Hills Thursday 6:00 AM - 10:42 PM Friday 6:00 AM - 10:42 PM Ambassador Road, Crown Hills Wicklow Drive, Leicester Saturday 6:00 AM - 10:42 PM Rowlatts Hill Road, Crown Hills Tithe Street, North Evington The Littleway, Leicester 54 bus Info Direction: Beaumont Leys Kitchener Road, North Evington Stops: 48 Trip Duration: 63 min Rosebery Street, North Evington Line Summary: Walshe Road, Goodwood, Greenacre Drive, Crown Hills, Rockingham Close, Crown Hills, Leicester Street, North Evington Ambassador Road, Crown Hills, Rowlatts Hill Road, Leicester Street, Leicester Crown Hills, Tithe Street, North Evington, Kitchener Road, North Evington, Rosebery Street, North St Saviour's Road, North Evington Evington, Leicester Street, North Evington, St Saviour's Road, North Evington, Blanklyn Avenue, Blanklyn Avenue, North Evington North Evington, Cork Street, North Evington, Ashover -

Annual Report

THE LOST VILLAGE OF ANDRESCHURCH 181 1 2 The Leicestershire Archaeological and 3 4 5 Historical Society 6 7 8 148th Annual Report 2002-2003 9 10 2002 1 Thursday Held in the Victorian Gallery, New Walk Museum The 2 10th October Leicester Mummies: scientific studies of life, disease and death 3 in ancient Egypt 4 Rosalie David, B.A., PhD., FRSA 5 Professor and Keeper of Egyptology, The Manchester Museum, 6 University of Manchester 7 8 Thursday Shopping in the Middle Ages 9 24th October Christopher C. Dyer, B.A., Ph.D., F.B.A., F.S.A., F.R.Hist.S. 10 Professor and Director, Centre for English Local History, 1 University of Leicester 2 3 Thursday Brian Allison Memorial Lecture 4 7th November Victorian Villas in Leicester 5 Grant Pitches M.A. A.R.I.B.A 6 Lecturer in architectural history, Institute of Continuing 7 Education, University of Cambridge 8 9 Thursday Annual General Meeting 10 21st November Held at the Guildhall, Leicester 1 Followed by a presentation by Dr Andrew Lacy on the Special 2 Collections in the University of Leicester Library 3 4 Thursday Exploring Leicestershire’s Churchyards 5 5th December Alan McWhirr, B.Sc., M.A., Ph.D., F.S.A., M.I.F.A. 6 Honorary Secretary of the Society, University Fellow, 7 University of Leicester 8 9 2003 10 Thursday Iron Age Britain and the Celtic myth 1 9th January Simon James, B.Sc., Ph.D., F.S.A. 2 School of Archaeology and and Ancient History, University of 3 Leicester 4 5 Thursday Treatment of the sick poor in Leicester: the North Evington 6 23rd January Poor Law Infirmary, 1905–30 7 Gerald T.