Physics and Chemistry of Gas in Planetary Nebulae

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2.5 Dimensional Radiative Transfer Modeling of Proto-Planetary Nebula Dust Shells with 2-DUST

PLANETARY NEBULAE: THEIR EVOLUTION AND ROLE IN THE UNIVERSE fA U Symposium, Vol. 209, 2003 S. Kwok, M. Dopita, and R. Sutherland, eds. 2.5 Dimensional Radiative Transfer Modeling of Proto-Planetary Nebula Dust Shells with 2-DUST Toshiya Ueta & Margaret Meixner Department of Astronomy, MC-221 , University of fllinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL 61801, USA ueta@astro. uiuc.edu, [email protected]. edu Abstract. Our observing campaign of proto-planetary nebula (PPN) dust shells has shown that the structure formation in planetary nebu- lae (PNs) begins as early as the late asymptotic. giant branch (AGB) phase due to intrinsically axisymmetric superwind. We describe our latest numerical efforts with a multi-dimensional dust radiative transfer code, 2-DUST, in order to explain the apparent dichotomy of the PPN mor- phology at the mid-IR and optical, which originates most likely from the optical depth of the shell combined with the effect of inclination angle. 1. Axisymmetric PPN Shells and Single Density Distribution Model Since the PPN phase predates the period of final PN shaping due to interactions of the stellar winds, we can investigate the origin of the PN structure formation by observationally establishing the material distribution in the PPN shells, in which pristine fossil records of AGB mass loss histories are preserved in their benign circumstellar environment. Our mid-IR and optical imaging surveys of PPN candidates in the past several years (Meixner at al. 1999; Ueta et al. 2000) have revealed that (1) PPN shells are intrinsically axisymmetric most likely due to equatorially-enhanced superwind mass loss at the end of the AGB phase and (2) varying degrees of equatorial enhancement in superwind would result in different optical depths of the PPN shell, thereby heavily influencing the mid-IR and optical morphologies. -

Filter Performance Comparisons for Some Common Nebulae

Filter Performance Comparisons For Some Common Nebulae By Dave Knisely Light Pollution and various “nebula” filters have been around since the late 1970’s, and amateurs have been using them ever since to bring out detail (and even some objects) which were difficult to impossible to see before in modest apertures. When I started using them in the early 1980’s, specific information about which filter might work on a given object (or even whether certain filters were useful at all) was often hard to come by. Even those accounts that were available often had incomplete or inaccurate information. Getting some observational experience with the Lumicon line of filters helped, but there were still some unanswered questions. I wondered how the various filters would rank on- average against each other for a large number of objects, and whether there was a “best overall” filter. In particular, I also wondered if the much-maligned H-Beta filter was useful on more objects than the two or three targets most often mentioned in publications. In the summer of 1999, I decided to begin some more comprehensive observations to try and answer these questions and determine how to best use these filters overall. I formulated a basic survey covering a moderate number of emission and planetary nebulae to obtain some statistics on filter performance to try to address the following questions: 1. How do the various filter types compare as to what (on average) they show on a given nebula? 2. Is there one overall “best” nebula filter which will work on the largest number of objects? 3. -

Planetary Nebulae Jacob Arnold AY230, Fall 2008

Jacob Arnold Planetary Nebulae Jacob Arnold AY230, Fall 2008 1 PNe Formation Low mass stars (less than 8 M) will travel through the asymptotic giant branch (AGB) of the familiar HR-diagram. During this stage of evolution, energy generation is primarily relegated to a shell of helium just outside of the carbon-oxygen core. This thin shell of fusing He cannot expand against the outer layer of the star, and rapidly heats up while also quickly exhausting its reserves and transferring its head outwards. When the He is depleted, Hydrogen burning begins in a shell just a little farther out. Over time, helium builds up again, and very abruptly begins burning, leading to a shell-helium-flash (thermal pulse). During the thermal-pulse AGB phase, this process repeats itself, leading to mass loss at the extended outer envelope of the star. The pulsations extend the outer layers of the star, causing the temperature to drop below the condensation temperature for grain formation (Zijlstra 2006). Grains are driven off the star by radiation pressure, bringing gas with them through collisions. The mass loss from pulsating AGB stars is oftentimes referred to as a wind. For AGB stars, the surface gravity of the star is quite low, and wind speeds of ~10 km/s are more than sufficient to drive off mass. At some point, a super wind develops that removes the envelope entirely, a phenomenon not yet fully understood (Bernard-Salas 2003). The central, primarily carbon-oxygen core is thus exposed. These cores can have temperatures in the hundreds of thousands of Kelvin, leading to a very strong ionizing source. -

Delite Eyepiece Between 100X and 200X for a Given Tele- Line for Tele Vue Optics

EQUIPMENT REVIEW to help prevent an errant eyepiece from blue, and twin-lobed, somewhat reminis- falling to the ground. cent of the Little Dumbbell Nebula (M76), When I test eyepieces, it’s important to although the emphasis was on the lobes Select these eyepieces to enhance your observing me to use them in a variety of telescopes so rather than the center. without ruining your credit. by Tom Trusock I can understand what aberrations the tele- Finally, I took the time to check the scope adds to the design. Through the contrast with the Fetus Nebula (NGC We test years, I’ve seen amateurs blame specific 7008). With a bright star just off the edge of aberrations on eyepiece design that were this planetary nebula, its large size and low the fault of the telescope. Always remem- surface brightness can make it difficult to ber, we deal with an optical system. pick out the distinctive shape, but it was in Because of this, I’m careful to review eye- clear view through the DeLites. pieces in various telescopes I am already familiar with. For this review, I used an Comparing sizes Tele Vue’s DeLite 18-inch f/4.5 Newtonian reflector These are excellent eyepieces. But which (equipped with the Tele Vue Paracorr), a one did I prefer? I found that my favorite 3.6-inch f/7 apochromatic refractor, and a eyepiece depended greatly on the telescope 6-inch f/15 Maksutov reflector. I used it in. Overall, each DeLite performed My testing showed all three scopes per- similarly, so I matched magnification to formed similarly, so the comments in gen- sky conditions. -

Planetary Nebulae

Planetary Nebulae A planetary nebula is a kind of emission nebula consisting of an expanding, glowing shell of ionized gas ejected from old red giant stars late in their lives. The term "planetary nebula" is a misnomer that originated in the 1780s with astronomer William Herschel because when viewed through his telescope, these objects appeared to him to resemble the rounded shapes of planets. Herschel's name for these objects was popularly adopted and has not been changed. They are a relatively short-lived phenomenon, lasting a few tens of thousands of years, compared to a typical stellar lifetime of several billion years. The mechanism for formation of most planetary nebulae is thought to be the following: at the end of the star's life, during the red giant phase, the outer layers of the star are expelled by strong stellar winds. Eventually, after most of the red giant's atmosphere is dissipated, the exposed hot, luminous core emits ultraviolet radiation to ionize the ejected outer layers of the star. Absorbed ultraviolet light energizes the shell of nebulous gas around the central star, appearing as a bright colored planetary nebula at several discrete visible wavelengths. Planetary nebulae may play a crucial role in the chemical evolution of the Milky Way, returning material to the interstellar medium from stars where elements, the products of nucleosynthesis (such as carbon, nitrogen, oxygen and neon), have been created. Planetary nebulae are also observed in more distant galaxies, yielding useful information about their chemical abundances. In recent years, Hubble Space Telescope images have revealed many planetary nebulae to have extremely complex and varied morphologies. -

Spring Semester 2010 Exam 3 – Answers a Planetary Nebula Is A

ASTR 1120H – Spring Semester 2010 Exam 3 – Answers PART I (70 points total) – 14 short answer questions (5 points each): 1. What is a planetary nebula? How long can a planetary nebula be observed? A planetary nebula is a luminous shell of gas ejected from an old, low- mass star. It can be observed for approximately 50,000 years; after that it its gases will have ceased to glow and it will simply fade from view. 2. What is a white dwarf star? How does a white dwarf change over time? A white dwarf star is a low-mass star that has exhausted all its nuclear fuel and contracted to a size roughly equal to the size of the Earth. It is supported against further contraction by electron degeneracy pressure. As a white dwarf ages, though, it will radiate, thereby cooling and getting less luminous. 3. Name at least three differences between Type Ia supernovae and Type II supernovae. Type Ia SN are intrinsically brighter than Type II SN. Type II SN show hydrogen emission lines; Type Ia SN don't. Type II SN are thought to arise from core collapse of a single, massive star. Type Ia SN are thought to arise from accretion from a binary companion onto a white dwarf star, pushing the white dwarf beyond the Chandrasekhar limit and causing a nuclear detonation that destroys the white dwarf. 4. Why was SN 1987A so important? SN 1987A was the first naked-eye SN in almost 400 years. It was the first SN for which a precursor star could be identified. -

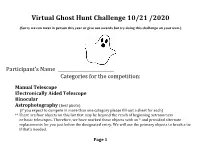

Ghost Hunt Challenge 2020

Virtual Ghost Hunt Challenge 10/21 /2020 (Sorry we can meet in person this year or give out awards but try doing this challenge on your own.) Participant’s Name _________________________ Categories for the competition: Manual Telescope Electronically Aided Telescope Binocular Astrophotography (best photo) (if you expect to compete in more than one category please fill-out a sheet for each) ** There are four objects on this list that may be beyond the reach of beginning astronomers or basic telescopes. Therefore, we have marked these objects with an * and provided alternate replacements for you just below the designated entry. We will use the primary objects to break a tie if that’s needed. Page 1 TAS Ghost Hunt Challenge - Page 2 Time # Designation Type Con. RA Dec. Mag. Size Common Name Observed Facing West – 7:30 8:30 p.m. 1 M17 EN Sgr 18h21’ -16˚11’ 6.0 40’x30’ Omega Nebula 2 M16 EN Ser 18h19’ -13˚47 6.0 17’ by 14’ Ghost Puppet Nebula 3 M10 GC Oph 16h58’ -04˚08’ 6.6 20’ 4 M12 GC Oph 16h48’ -01˚59’ 6.7 16’ 5 M51 Gal CVn 13h30’ 47h05’’ 8.0 13.8’x11.8’ Whirlpool Facing West - 8:30 – 9:00 p.m. 6 M101 GAL UMa 14h03’ 54˚15’ 7.9 24x22.9’ 7 NGC 6572 PN Oph 18h12’ 06˚51’ 7.3 16”x13” Emerald Eye 8 NGC 6426 GC Oph 17h46’ 03˚10’ 11.0 4.2’ 9 NGC 6633 OC Oph 18h28’ 06˚31’ 4.6 20’ Tweedledum 10 IC 4756 OC Ser 18h40’ 05˚28” 4.6 39’ Tweedledee 11 M26 OC Sct 18h46’ -09˚22’ 8.0 7.0’ 12 NGC 6712 GC Sct 18h54’ -08˚41’ 8.1 9.8’ 13 M13 GC Her 16h42’ 36˚25’ 5.8 20’ Great Hercules Cluster 14 NGC 6709 OC Aql 18h52’ 10˚21’ 6.7 14’ Flying Unicorn 15 M71 GC Sge 19h55’ 18˚50’ 8.2 7’ 16 M27 PN Vul 20h00’ 22˚43’ 7.3 8’x6’ Dumbbell Nebula 17 M56 GC Lyr 19h17’ 30˚13 8.3 9’ 18 M57 PN Lyr 18h54’ 33˚03’ 8.8 1.4’x1.1’ Ring Nebula 19 M92 GC Her 17h18’ 43˚07’ 6.44 14’ 20 M72 GC Aqr 20h54’ -12˚32’ 9.2 6’ Facing West - 9 – 10 p.m. -

SHAPING the WIND of DYING STARS Noam Soker

Pleasantness Review* Department of Physics, Technion, Israel The role of jets in the common envelope evolution (CEE) and in the grazing envelope evolution (GEE) Cambridge 2016 Noam Soker •Dictionary translation of my name from Hebrew to English (real!): Noam = Pleasantness Soker = Review A short summary JETS See review accepted for publication by astro-ph in May 2016: Soker, N., 2016, arXiv: 160502672 A very short summary JFM See review accepted for publication by astro-ph in May 2016: Soker, N., 2016, arXiv: 160502672 A full summary • Jets are unavoidable when the companion enters the common envelope. They are most likely to continue as the secondary star enters the envelop, and operate under a negative feedback mechanism (the Jet Feedback Mechanism - JFM). • Jets: Can be launched outside and Secondary inside the envelope star RGB, AGB, Red Giant Massive giant primary star Jets Jets Jets: And on its surface Secondary star RGB, AGB, Red Giant Massive giant primary star Jets A full summary • Jets are unavoidable when the companion enters the common envelope. They are most likely to continue as the secondary star enters the envelop, and operate under a negative feedback mechanism (the Jet Feedback Mechanism - JFM). • When the jets mange to eject the envelope outside the orbit of the secondary star, the system avoids a common envelope evolution (CEE). This is the Grazing Envelope Evolution (GEE). Points to consider (P1) The JFM (jet feedback mechanism) is a negative feedback cycle. But there is a positive ingredient ! In the common envelope evolution (CEE) more mass is removed from zones outside the orbit. -

Experiencing Hubble

PRESCOTT ASTRONOMY CLUB PRESENTS EXPERIENCING HUBBLE John Carter August 7, 2019 GET OUT LOOK UP • When Galaxies Collide https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HP3x7TgvgR8 • How Hubble Images Get Color https://www.youtube.com/watch? time_continue=3&v=WSG0MnmUsEY Experiencing Hubble Sagittarius Star Cloud 1. 12,000 stars 2. ½ percent of full Moon area. 3. Not one star in the image can be seen by the naked eye. 4. Color of star reflects its surface temperature. Eagle Nebula. M 16 1. Messier 16 is a conspicuous region of active star formation, appearing in the constellation Serpens Cauda. This giant cloud of interstellar gas and dust is commonly known as the Eagle Nebula, and has already created a cluster of young stars. The nebula is also referred to the Star Queen Nebula and as IC 4703; the cluster is NGC 6611. With an overall visual magnitude of 6.4, and an apparent diameter of 7', the Eagle Nebula's star cluster is best seen with low power telescopes. The brightest star in the cluster has an apparent magnitude of +8.24, easily visible with good binoculars. A 4" scope reveals about 20 stars in an uneven background of fainter stars and nebulosity; three nebulous concentrations can be glimpsed under good conditions. Under very good conditions, suggestions of dark obscuring matter can be seen to the north of the cluster. In an 8" telescope at low power, M 16 is an impressive object. The nebula extends much farther out, to a diameter of over 30'. It is filled with dark regions and globules, including a peculiar dark column and a luminous rim around the cluster. -

February 14, 2015 7:00Pm at the Herrett Center for Arts & Science Colleagues, College of Southern Idaho

Snake River Skies The Newsletter of the Magic Valley Astronomical Society www.mvastro.org Membership Meeting President’s Message Saturday, February 14, 2015 7:00pm at the Herrett Center for Arts & Science Colleagues, College of Southern Idaho. Public Star Party Follows at the It’s that time of year when obstacles appear in the sky. In particular, this year is Centennial Obs. loaded with fog. It got in the way of letting us see the dance of the Jovian moons late last month, and it’s hindered our views of other unique shows. Still, members Club Officers reported finding enough of a clear sky to let us see Comet Lovejoy, and some great photos by members are popping up on the Facebook page. Robert Mayer, President This month, however, is a great opportunity to see the benefit of something [email protected] getting in the way. Our own Chris Anderson of the Herrett Center has been using 208-312-1203 the Centennial Observatory’s scope to do work on occultation’s, particularly with asteroids. This month’s MVAS meeting on Feb. 14th will give him the stage to Terry Wofford, Vice President show us just how this all works. [email protected] The following weekend may also be the time the weather allows us to resume 208-308-1821 MVAS-only star parties. Feb. 21 is a great window for a possible star party; we’ll announce the location if the weather permits. However, if we don’t get that Gary Leavitt, Secretary window, we’ll fall back on what has become a MVAS tradition: Planetarium night [email protected] at the Herrett Center. -

A Basic Requirement for Studying the Heavens Is Determining Where In

Abasic requirement for studying the heavens is determining where in the sky things are. To specify sky positions, astronomers have developed several coordinate systems. Each uses a coordinate grid projected on to the celestial sphere, in analogy to the geographic coordinate system used on the surface of the Earth. The coordinate systems differ only in their choice of the fundamental plane, which divides the sky into two equal hemispheres along a great circle (the fundamental plane of the geographic system is the Earth's equator) . Each coordinate system is named for its choice of fundamental plane. The equatorial coordinate system is probably the most widely used celestial coordinate system. It is also the one most closely related to the geographic coordinate system, because they use the same fun damental plane and the same poles. The projection of the Earth's equator onto the celestial sphere is called the celestial equator. Similarly, projecting the geographic poles on to the celest ial sphere defines the north and south celestial poles. However, there is an important difference between the equatorial and geographic coordinate systems: the geographic system is fixed to the Earth; it rotates as the Earth does . The equatorial system is fixed to the stars, so it appears to rotate across the sky with the stars, but of course it's really the Earth rotating under the fixed sky. The latitudinal (latitude-like) angle of the equatorial system is called declination (Dec for short) . It measures the angle of an object above or below the celestial equator. The longitud inal angle is called the right ascension (RA for short). -

President's Message

Journal of the Northern Sydney Astronomical Society Inc. February 2019 In this issue President’s Message Page 1: President’s message Editorial i everyone. Object of the Month as it had been an idea Page 2: Results of the Photo HWhat a magnificent summer! waiting for someone to bring it to life for Competition It seems ages since the lovely summer days some time. Page 5: Results of the Article have landed on our holiday period in such This past two months’ contributions have Competition a comprehensive way. It has been a great been interesting and seen some wonderful Page 7: The Jupiter/Venus Conjunction holiday period for me and I hope you have images come to life. all had such a great time as I have had. It showcases the skills that some of our The last month’s images and videos I am equally pleased to see the Reflections members have and a big congratulation to of Wirtanen 46P comet, along with magazine has had a resurgence and I Kym Haines, the winner for this month, this month’s incredible photo of M42 encourage everyone to take an interest in Phil Angilley and Daniel Patos, the runner- exemplify the talents that can be found it. ups, for their excellent work. amongst our club members. We are expanding the source of A quick shout out to some upcoming contributions for the magazine with the Kym’s M42 photo as seen on page 2 is events. inclusion of the Object of the Month and magnificent and the colours and framing In April we will be running our New other items of interest to our community.