Anti-Inflammatory Therapy in Tendinopathy: the Role Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Pathomorpholog.Pdf

Ukrаiniаn Medicаl Stomаtologicаl Аcаdemy THE DEPАRTАMENT OF PАTHOLOGICАL АNАTOMY WITH SECTIONSL COURSE MАNUАL for the foreign students GENERАL PАTHOMORPHOLOGY Poltаvа-2020 УДК:616-091(075.8) ББК:52.5я73 COMPILERS: PROFESSOR I. STАRCHENKO ASSOCIATIVE PROFESSOR O. PRYLUTSKYI АSSISTАNT A. ZADVORNOVA ASSISTANT D. NIKOLENKO Рекомендовано Вченою радою Української медичної стоматологічної академії як навчальний посібник для іноземних студентів – здобувачів вищої освіти ступеня магістра, які навчаються за спеціальністю 221 «Стоматологія» у закладах вищої освіти МОЗ України (протокол №8 від 11.03.2020р) Reviewers Romanuk A. - MD, Professor, Head of the Department of Pathological Anatomy, Sumy State University. Sitnikova V. - MD, Professor of Department of Normal and Pathological Clinical Anatomy Odessa National Medical University. Yeroshenko G. - MD, Professor, Department of Histology, Cytology and Embryology Ukrainian Medical Dental Academy. A teaching manual in English, developed at the Department of Pathological Anatomy with a section course UMSA by Professor Starchenko II, Associative Professor Prylutsky OK, Assistant Zadvornova AP, Assistant Nikolenko DE. The manual presents the content and basic questions of the topic, practical skills in sufficient volume for each class to be mastered by students, algorithms for describing macro- and micropreparations, situational tasks. The formulation of tests, their number and variable level of difficulty, sufficient volume for each topic allows to recommend them as preparation for students to take the licensed integrated exam "STEP-1". 2 Contents p. 1 Introduction to pathomorphology. Subject matter and tasks of 5 pathomorphology. Main stages of development of pathomorphology. Methods of pathanatomical diagnostics. Methods of pathomorphological research. 2 Morphological changes of cells as response to stressor and toxic damage 8 (parenchimatouse / intracellular dystrophies). -

Role of Brain Stimulation and the Blood–Brain Interface

biomolecules Review Monitoring and Modulating Inflammation-Associated Alterations in Synaptic Plasticity: Role of Brain Stimulation and the Blood–Brain Interface Maximilian Lenz 1,*, Amelie Eichler 1 and Andreas Vlachos 1,2,3,* 1 Department of Neuroanatomy, Institute of Anatomy and Cell Biology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Freiburg, 79104 Freiburg, Germany 2 Center Brain Links Brain Tools, University of Freiburg, 79110 Freiburg, Germany 3 Center for Basics in NeuroModulation (NeuroModulBasics), Faculty of Medicine, University of Freiburg, 79106 Freiburg, Germany * Correspondence: [email protected] (M.L.); [email protected] (A.V.) Abstract: Inflammation of the central nervous system can be triggered by endogenous and exogenous stimuli such as local or systemic infection, trauma, and stroke. In addition to neurodegeneration and cell death, alterations in physiological brain functions are often associated with neuroinflammation. Robust experimental evidence has demonstrated that inflammatory cytokines affect the ability of neurons to express plasticity. It has been well-established that inflammation-associated alterations in synaptic plasticity contribute to the development of neuropsychiatric symptoms. Nevertheless, diagnostic approaches and interventional strategies to restore inflammatory deficits in synaptic plasticity are limited. Here, we review recent findings on inflammation-associated alterations in synaptic plasticity and the potential role of the blood–brain interface, i.e., the blood–brain barrier, Citation: Lenz, M.; Eichler, A.; in modulating synaptic plasticity. Based on recent findings indicating that brain stimulation promotes Vlachos, A. Monitoring and plasticity and modulates vascular function, we argue that clinically employed non-invasive brain Modulating Inflammation-Associated stimulation techniques, such as transcranial magnetic stimulation, could be used for monitoring and Alterations in Synaptic Plasticity: modulating inflammation-induced alterations in synaptic plasticity. -

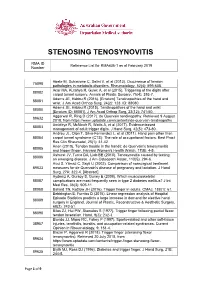

Reference List Concerning De Quervain Tenosynovitis

STENOSING TENOSYNOVITIS RMA ID Reference List for RMA436-1 as at February 2019 Number Abate M, Schiavone C, Salini V, et al (2013). Occurrence of tendon 75098 pathologies in metabolic disorders. Rheumatology, 52(4): 599-608. Acar MA, Kutahya H, Gulec A, et al (2015). Triggering of the digits after 88082 carpal tunnel surgery. Annals of Plastic Surgery, 75(4): 393-7. Adams JE, Habbu R (2016). [Erratum] Tendinopathies of the hand and 88081 wrist. J Am Acad Orthop Surg, 24(2): 123. ID: 88080. Adams JE, Habbu R (2015). Tendinopathies of the hand and wrist 88080 [Erratum ID: 88081]. J Am Acad Orthop Surg, 23(12): 741-50. Aggarwal R, Ring D (2017). de Quervain tendinopathy. Retrieved 9 August 89632 2018, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/de-quervain-tendinopathy Amirfeyz R, McNinch R, Watts A, et al (2017). Evidence-based 88083 management of adult trigger digits. J Hand Surg, 42(5): 473-80. Andreu JL, Oton T, Silva-Fernandez L, et al (2011). Hand pain other than 88084 carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS): The role of occupational factors. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol, 25(1): 31-42. Anon (2010). Tendon trouble in the hands: de Quervain's tenosynovitis 88085 and trigger finger. Harvard Women's Health Watch, 17(8): 4-5. Ashurst JV, Turco DA, Lieb BE (2010). Tenosynovitis caused by texting: 88086 an emerging disease. J Am Osteopath Assoc, 110(5): 294-6. Avci S, Yilmaz C, Sayli U (2002). Comparison of nonsurgical treatment 89633 measures for de Quervain's disease of pregnancy and lactation. J Hand Surg, 27A: 322-4. -

De Quervain's Syndrome

De Quervain's syndrome What is it? Treatment options are: Through a transverse or longitudinal De Quervain's syndrome is a painful condition 1. Avoiding activities that cause pain, if incision, and protecting the nerve that affects tendons where they run through a possible branches just under the skin, the surgeon tunnel on the thumb side of the wrist. widens the tendon tunnel by slitting its roof. The tunnel roof forms again as the 2. Using a wrist/thumb splint, which can split heals, but it is wider and the What is the cause? often be obtained from a sports shop or a physiotherapist. It needs to immobilize tendons have sufficient room to move the thumb as well as the wrist. without pain. It appears without obvious cause in many cases. Pain relief is usually rapid. The scar may Mothers of small babies seem particularly prone 3. Steroid injection relieves the pain in be sore and unsightly for several weeks. to it, but whether this is due to hormonal Because the nerve branches were gently changes after pregnancy or due to lifting the about 70% of cases. The risks of injection are small, but it very occasionally causes moved to see the tunnel, transient baby repeatedly is not known. There is little temporary numbness can occur on the evidence that it is caused by work activities, but some thinning or colour change in the skin at the site of injection. back of the hand or thumb. Other risks the pain can certainly be aggravated by hand are the risks of any surgery such as use at work, at home, in the garden or at sport. -

Histologische Versagensanalyse Von 114 Metall/Metall-Großkopfhüftendoprothesen

Aus der Orthopädischen Universitätsklinik der medizinischen Fakultät der Otto-von-Guericke-Universität Magdeburg Direktor: Prof. Dr. med. C. H. Lohmann Histologische Versagensanalyse von 114 Metall/Metall-Großkopfhüftendoprothesen D i s s e r t a t i o n zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades Dr. med. (doctor medicinae) an der Medizinischen Fakultät der Otto-von-Guericke-Universität Magdeburg vorgelegt von Tina Müller aus Magdeburg Magdeburg Oktober 2016 Dokumentationsblatt Müller, Tina: Histologische Versagensanalyse von 114 Metall/Metall-Großkopfhüftendoprothesen – 2016. – 76 Bl.: 24 Abb., 6 Tab. Die Studie analysierte klinisch, radiologisch, histologisch und anhand intraoperativer Befunde 114 Versagensfälle einer modularen Metall/Metall-Großkopfhüftendoprothese. Alle unter- suchten Patienten zeigten bereits frühzeitig nach Implantation der Primärprothese klinische Symptome, welche auf eine Prothesenlockerung hindeuteten. Schon während der Revisi- onsoperation waren charakteristische Veränderungen im periprothetischen Gewebe makro- skopisch sichtbar. Die gewonnenen Gewebeproben wurden in 5%igem Formalin fixiert. Die histologischen Proben wurden mit Hämatoxylin-Eosin gefärbt, mit monoklonalen anti-CD3- sowie anti-CD68-Antikörpern markiert und auf spezifische Gewebsveränderungen untersucht. Die histomorphologischen Untersuchungen wiesen in der Mehrheit der Fälle eine Fremdkör- perreaktion auf. Mikroskopisch wurden in der Monozyten-/Makrophagenzytologie schwarze Metallpartikel gefunden. Es lässt sich vermuten, dass es bei Verwendung verschiedener -

(UED). a Health Care Provider Shall Determine the Nature of an Upper Extremity Disorder Before Initiating Treatment

1 REVISOR 5221.6300 5221.6300 UPPER EXTREMITY DISORDERS. Subpart 1. Diagnostic procedures for treatment of upper extremity disorders (UED). A health care provider shall determine the nature of an upper extremity disorder before initiating treatment. A. An appropriate history and physical examination must be performed and documented. Based on the history and physical examination the health care provider must at each visit assign the patient to the appropriate clinical category according to subitems (1) to (6). The diagnosis must be documented in the medical record. Patients may have multiple disorders requiring assignment to more than one clinical category. This part does not apply to upper extremity conditions due to a visceral, vascular, infectious, immunological, metabolic, endocrine, systemic neurologic, or neoplastic disease process, fractures, lacerations, amputations, or sprains or strains with complete tissue disruption. (1) Epicondylitis. This clinical category includes medial epicondylitis and lateral epicondylitis, ICD-9-CM codes 726.31 and 726.32. (2) Tendonitis of the forearm, wrist, and hand. This clinical category encompasses any inflammation, pain, tenderness, or dysfunction or irritation of a tendon, tendon sheath, tendon insertion, or musculotendinous junction in the upper extremity at or distal to the elbow due to mechanical injury or irritation, including, but not limited to, the diagnoses of tendonitis, tenosynovitis, tendovaginitis, peritendinitis, extensor tendinitis, de Quervain's syndrome, intersection syndrome, flexor tendinitis, and trigger digit, including, but not limited to, ICD-9-CM codes 726.4, 726.8, 726.9, 726.90, 727, 727.0, 727.00, 727.03, 727.04, 727.05, 727.09, 727.2, 727.3, 727.4 to 727.49, 727.8 to 727.82, 727.89, and 727.9. -

Inflammation

Inflammation II. 1 Definitions Inflammation is defined as local reaction of vascularized living tissue to local injury, characterized by movement of fluid and leukocytes from the blood into the extravascular space. According the time frame is divided into two categories: acute and chronic. Function: • destroys, dilutes or walls off injurious agents • one of body’s non-specific defense mechanisms • begins the process of healing and repair 1.1 Acute Inflammation Rapid onset, usually short duration Microscopy • neutrophils dominate • other cellular elements are also involved (monocytes/macrophages, platelets, mast cells) • protein rich exudate, especially fibrin Associations • necrosis • pyogenic bacteria 1.2 Chronic Inflammation Usually long duration, but in some cases may be short. May follow acute inflammation or may have an insiduous onset (without an apparent prelude of acute inflammation). Microscopy • mononuclear cells dominate – lymphocytes – plasma cells (plasmocytes) – monocytes/macrophages • other cellular elements are also involved (eosinophils, neutrophils in active“ inflammation)1 ” • In granulomas are typical Langhans cells, large, multinuclear elements on the periphery of tuberculous granulomas. Nuclei are sometimes arranged in a horseshoe shape formation. Foreign body cells are similar, usually smaller, the horseshape formation of nuclei is not present. Both these elements are modified macrophages. • evidence of healing — fibroblasts, capillaries, fibrosis Associations • long term stimulation of immune system, autoimmunity • viral infections -

![De Quervain's Tenosynovitis: [11] Lee KH, Kang CN, Lee BG, a Case-Control Study with Prospe Tively Jung WS, Kim DY, Lee CH](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6782/de-quervains-tenosynovitis-11-lee-kh-kang-cn-lee-bg-a-case-control-study-with-prospe-tively-jung-ws-kim-dy-lee-ch-886782.webp)

De Quervain's Tenosynovitis: [11] Lee KH, Kang CN, Lee BG, a Case-Control Study with Prospe Tively Jung WS, Kim DY, Lee CH

Chapter De Quervain’s Tenosynovitis: Effective Diagnosis and Evidence-Based Treatment Jenson Mak Abstract De Quervain’s tenosynovitis (DQT) is a repetitive stress condition located at the first dorsal compartment of the wrist at the radial styloid. The extensor pollicis brevis (EPB) and abductor pollicis longus (APL) tendons and each tendon sheath are inflamed and this may result in thickening of the first dorsal extensor sheath. Workers who perform repetitive activities of the wrist and hand and those who rou- tinely use their thumbs in grasping and pinching motions in a repetitive manner are most susceptible to DQT. Conservative treatments include activity modification, modalities, orthotics, and manual therapy. This chapter identifies, in an evidence base manner through the literature, the most effective diagnostic measures for DQT. It also examines the evidence base on (or lack thereof) the treatment or treat- ment combinations to reduce pain and improve functional outcomes for patients with DQT. Keywords: De Quervain’s tenosynovitis, diagnosis, treatment, workplace, evidence-based 1. Introduction In 1893, Paul Jules Tillaux described a painful crepitus sign (Aïe crépitant de Tillaux)—tenosynovitis of the adductor and the short extensor of the thumb. In 1894, Fritz de Quervain, a Swiss surgeon, first described tenosynovitis on December 18, 1894, in Mrs. D., a 35-year-old woman who had severe pain in the extensor muscle region of the thumb, excluding tuberculosis. “It is a condition affecting the tendon sheaths of the abductor pollicis longus, and the extensor pollicis brevis. It has definite symptoms and signs. The condition may affect other extensor tendons at the wrist” [1]. -

Protective Effects of Zinc-L-Carnosine /Vitamin E on Aspirin- Induced Gastroduodenal Injury in Dogs

PROTECTIVE EFFECTS OF ZINC-L-CARNOSINE /VITAMIN E ON ASPIRIN- INDUCED GASTRODUODENAL INJURY IN DOGS MASTER’S THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Science Degree in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Mieke Baan, DVM, MVR ***** The Ohio State University 2009 Master’s Examination Committee: Professor Robert G. Sherding, Adviser Professor Stephen P. DiBartola Associate Professore Susan E. Johnson Approved by Adviser Veterinary Clinical Sciences Graduate Program ! Copyright by Mieke Baan 2009 ABSTRACT Zinc plays a role in many biochemical functions, including DNA, RNA, and protein synthesis. The dipeptide carnosine forms a stable complex with zinc, which has a protective effect against gastric epithelial injury in-vitro and in-vivo. This randomized double-blinded placebo-controlled study investigated the protective effects of zinc-L-carnosine in combination with alpha-tocopheryl acetate (vitamin E) on the development of aspirin-induced gastrointestinal (GI) lesions in dogs. Eighteen mixed-breed dogs (mean 20.6 kg) were negative for parasites, and had normal blood work evaluations, and gastroduodenoscopic exams. On days 0 – 35, dogs were treated with 1 tablet (n=6) or 2 tablets (n=6) of 30 mg zinc-L-carnosine/ 30 IU vitamin E q12h PO, or a placebo (n=6). On days 7 – 35, all dogs were given 25 mg/kg buffered aspirin q8h PO. Endoscopy was performed on Days -1, 14, 21, and 35, and GI lesions (hemorrhages, erosions, or ulcers) were scored using a 12-point grading scale. Repeated measures ANOVA was used for statistical evaluation. The significance level was set at p ! 0.05. -

Mcqs and Emqs in Surgery

1 The metabolic response to injury Multiple choice questions ➜ Homeostasis B Every endocrine gland plays an equal 1. Which of the following statements part. about homeostasis are false? C They produce a model of several phases. A It is defined as a stable state of the D The phases occur over several days. normal body. E They help in the process of repair. B The central nervous system, heart, lungs, ➜ kidneys and spleen are the essential The recovery process organs that maintain homeostasis at a 4. With regard to the recovery process, normal level. identify the statements that are true. C Elective surgery should cause little A All tissues are catabolic, resulting in repair disturbance to homeostasis. at an equal pace. D Emergency surgery should cause little B Catabolism results in muscle wasting. disturbance to homeostasis. C There is alteration in muscle protein E Return to normal homeostasis after breakdown. an operation would depend upon the D Hyperalimentation helps in recovery. presence of co-morbid conditions. E There is insulin resistance. ➜ Stress response ➜ Optimal perioperative care 2. In stress response, which of the 5. Which of the following statements are following statements are false? true for optimal perioperative care? A It is graded. A Volume loss should be promptly treated B Metabolism and nitrogen excretion are by large intravenous (IV) infusions of related to the degree of stress. fluid. C In such a situation there are B Hypothermia and pain are to be avoided. physiological, metabolic and C Starvation needs to be combated. immunological changes. D Avoid immobility. D The changes cannot be modified. -

Inflammation Hedwig S

91731_ch02 12/8/06 7:31 PM Page 37 2 Inflammation Hedwig S. Murphy Overview Of Inflammation Leukocytes Traverse the Endothelial Cell Barrier to Gain Acute Inflammation Access to the Tissue Vascular Events Leukocyte Functions in Acute Inflammation Regulation of Vascular and Tissue Fluids Phagocytosis Plasma-Derived Mediators of Inflammation Neutrophil Enzymes Hageman Factor Oxidative and Nonoxidative Bactericidal Activity Kinins Regulation of Inflammation Complement system and the membrane attack complex Common Intracellular Pathways Complement system and proinflammatory molecules Outcomes of Acute Inflammation Cell-Derived Mediators of Inflammation Chronic Inflammation Arachidonic Acid and Platelet-Activating Factor Cells Involved in Chronic Inflammation Prostanoids, Leukotrienes, and Lipoxins Injury and Repair in Chronic Inflammation Cytokines Extended Inflammatory Response Reactive Oxygen Species Altered Repair Mechanisms Stress Proteins Granulomatous Inflammation Neurokinins Chronic Inflammation and Malignancy Extracellular Matrix Mediators Systemic Manifestations of Inflammation Cells of Inflammation Leukocyte Recruitment in Acute Inflammation Leukocyte Adhesion Chemotactic Molecules nflammation is the reaction of a tissue and its microcircu- blood. Rudolf Virchow first described inflammation as a reaction lation to a pathogenic insult. It is characterized by elabora- to prior tissue injury. To the four cardinal signs he added a fifth: Ition of inflammatory mediators and movement of fluid and functio laesa (loss of function). Virchow’s pupil Julius Cohn- leukocytes from the blood into extravascular tissues. This re- heim was the first to associate inflammation with emigration of sponse localizes and eliminates altered cells, foreign particles, leukocytes through the walls of the microvasculature. At the end microorganisms, and antigens and paves the way for the return of the 19th century, the role of phagocytosis in inflammation to normal structure and function. -

Research Article Prevalence and Awareness Evaluation of De

Available online www.ijpras.com International Journal of Pharmaceutical Research & Allied Sciences, 2020, 9(4):151-157 ISSN : 2277-3657 Research Article CODEN(USA) : IJPRPM Prevalence and Awareness Evaluation of De Quervain’s Tenosynovitis among Students in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Bashar Reada1, Nawaf Alshaebi2*, Khalid Almaghrabi2, Abdullah Alshuaibi2, Arwa Abulnaja3, Khames Alzahrani4 1 Department of Medicine, MBBS, FSCSC, College of Medicine, King Abdulaziz University Hospital, Jeddah, KSA. 2 Department of Medicine, Undergraduate, College of Medicine, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, KSA. 3 Department of Medicine, Medical Intern, College of Medicine, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, KSA. 4 Department of Medicine, BDS, Ministry of Health, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. *Email: nawafalshaebi @ hotmail.com ABSTRACT Introduction: De Quervain's tenosynovitis is characterized by inflammation and thickening of the tendons of the extensor pollicis brevis and abductor pollicis longus muscles and the synovial sheath, leading to a common cause of wrist pain that typically occurs in adults. This condition has been given several other names such as texting tenosynovitis, BlackBerry thumb, washerwoman's sprain, gamer’s thumb, teen texting tendonitis, WhatsAppitis, and radial styloid tenosynovitis, all of which involve repeated thumb pinching and wrist movement. Objectives: The purpose of this study was to determine the prevalence of de Quervain’s tenosynovitis among students using smartphones in Saudi Arabia. Many studies have been conducted on this disease in other countries, but not many have been performed in Saudi Arabia. Our aim was to obtain more information about the disease prevalence among students in Saudi Arabia. Our secondary objective was to determine the correlation of the condition with different demographics and risk factors in our study population, such as age, sex, and time spent texting.