Harbingers of Change.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

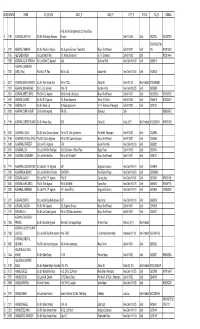

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 20001 MUDKONDWAR SHRUTIKA HOSPITAL, TAHSIL Male 9420020369 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PRASHANT NAMDEORAO OFFICE ROAD, AT/P/TAL- GEORAI, 431127 BEED Maharashtra 20002 RADHIKA BABURAJ FLAT NO.10-E, ABAD MAINE Female 9886745848 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PLAZA OPP.CMFRI, MARINE 8281300696 DRIVE, KOCHI, KERALA 682018 Kerela 20003 KULKARNI VAISHALI HARISH CHANDRA RESEARCH Female 0532 2274022 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 MADHUKAR INSTITUTE, CHHATNAG ROAD, 8874709114 JHUSI, ALLAHABAD 211019 ALLAHABAD Uttar Pradesh 20004 BICHU VAISHALI 6, KOLABA HOUSE, BPT OFFICENT Female 022 22182011 / NOT RENEW SHRIRANG QUARTERS, DUMYANE RD., 9819791683 COLABA 400005 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20005 DOSHI DOLLY MAHENDRA 7-A, PUTLIBAI BHAVAN, ZAVER Female 9892399719 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 ROAD, MULUND (W) 400080 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20006 PRABHU SAYALI GAJANAN F1,CHINTAMANI PLAZA, KUDAL Female 02362 223223 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 OPP POLICE STATION,MAIN ROAD 9422434365 KUDAL 416520 SINDHUDURG Maharashtra 20007 RUKADIKAR WAHEEDA 385/B, ALISHAN BUILDING, Female 9890346988 DR.NAUSHAD.INAMDAR@GMA RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 BABASAHEB MHAISAL VES, PANCHIL NAGAR, IL.COM MEHDHE PLOT- 13, MIRAJ 416410 SANGLI Maharashtra 20008 GHORPADE TEJAL A-7 / A-8, SHIVSHAKTI APT., Male 02312650525 / NOT RENEW CHANDRAHAS GIANT HOUSE, SARLAKSHAN 9226377667 PARK KOLHAPUR Maharashtra 20009 JAIN MAMTA -

The Examiner · Apr 18

THE EXAMINER · APR 18 - MAY 08, 2020 · 1 www.the-examiner.org 171 Years A CATHOLIC NEWSWEEKLY - Est 1850 • 171 years of publication • MUMBAI • Vol. 64 No. 15 • APR 18 - MAY 08, 2020 • Rs. 15/- Editor-in-Chief Fr Anthony Charanghat EDITORIAL BOARD: 3 HOPE IN HIS MERCY Managing Editor: Editorial Fr Joshan Rodrigues Members: 4 THE “JOYFUL” MYSTERY OF EASTER! Adrian Rosario Carol Andrade 5 TAKING YOUR PARISH INTO Dr Astrid Lobo Gajiwala CYBERSPACE ASST EDITOR: 7 WHAT TO DO ON DIVINE Fr Nigel Barrett MERCY SUNDAY? ART DIRECTOR: Rosetta Martins 8 LIVING JUSTICE, PEACE AND CONTENTS INTEGRITY OF CREATION ELECTRONIC MEDIA: Neil D'Souza 9 PARISHES STAY STRONG IN THE FAITH ADVERTISING: John Braganza UNDER LOCKDOWN PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY : Fr Anthony Charanghat 11 PANDEMIC RESPONSE: CHURCH IN for the Owners, MUMBAI’S HEART BEATS The Examiner Trust, FOR THE POOR Regn. No. E 10398 Bom. under the Bombay 12 A CLERGY-CENTRED CHURCH OR Public Trust Act, 1950. CHRIST-CENTRED COMMUNITY? AT: ACE PRINTERS 13 BRINGING THE EUCHARIST ALIVE IN 212, Pragati Industrial Estate, TIMES OF CRISIS Delisle Road, Lower Parel, Mumbai 400013 14 TEN WAYS THAT THE POST-COVID Tel.: 2263 0397 CHURCH WILL BE DIFFERENT OFFICE ADDRESS: Eucharistic Congress Bldg. III, 16 SOMEWHERE OVER THE RAINBOW 1st Floor, 5 Convent Street (Near Regal Cinema), Mumbai 400001 17 WHAT’S IN YOUR HAND? Tel: 2202 0221 / 2283 2807 19 "FEED MY LAMBS, TEND MY SHEEP" 2288 6585 20 THE TIME IS RIPE FOR A Email: TRANSVALUATION OF VALUES [email protected] [email protected] 21 A PERSONAL REFLECTION VIS-À-VIS [email protected] THE PANDEMIC (Courier surcharge for individual 23 "JESUS WEPT"(JN 11:35) copies outside Mumbai, Navi Mumbai and Thane @ Rs. -

Harish Hande Dr

Case: Solar Electric Light Co. India –Harish Hande Dr. Jack M. Wilson, Distinguished Professor of Higher Education, Emerging Technologies, and Innovation Entrepreneurship © 2012 ff -Jack M. Wilson, Distinguished Professor Case: SELCO -Harish Hande 1 The Problem • An estimated 1.2 billion people – 17% of the global population – did not have access to electricity in 2013, 84 million fewer than in the previous year. – Many more suffer from supply that is of poor quality. – More than 95% of those living without electricity are in countries in sub-Saharan Africa and developing Asia, and they are predominantly in rural areas (around 80% of the world total). – While still far from complete, progress in providing electrification in urban areas has outpaced that in rural areas two to one since 2000. • International Energy Agency • http://www.worldenergyoutlook.org/resources/energydevelopment/energyaccessdatabase/ • Of those about 400 million are in India alone. Entrepreneurship © 2012 ff -Jack M. Wilson, Distinguished Professor Case: SELCO -Harish Hande 2 Harish Hande ‘98 ‘00 • UML MS ‘98 renewable energy engineering • UML PhD ‘00 in mechanical engineering (energy) • co-founded Solar Electric Light Co. India in 1995. – As SELCO’s managing director, he has pioneered access to solar electricity for more than half a million people in India, where more than half the population does not have electricity, through customized home-lighting systems and innovative financing. • Hande received the 2011 Magsaysay Award, widely considered Asia’s equivalent of the Nobel Prize, • One of 21 Young Leaders for India’s 21st Century by Business Today • Social Entrepreneur of the Year for 2007 by the Schwab Foundation for Social Entrepreneurship and the Nand and Jeep Khemkha Foundation. -

Section 124- Unpaid and Unclaimed Dividend

Sr No First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 ASHOK KUMAR GOLCHHA 305 ASHOKA CHAMBERS ADARSHNAGAR HYDERABAD 500063 0000000000B9A0011390 36.00 2 ADAMALI ABDULLABHOY 20, SUKEAS LANE, 3RD FLOOR, KOLKATA 700001 0000000000B9A0050954 150.00 3 AMAR MANOHAR MOTIWALA DR MOTIWALA'S CLINIC, SUNDARAM BUILDING VIKRAM SARABHAI MARG, OPP POLYTECHNIC AHMEDABAD 380015 0000000000B9A0102113 12.00 4 AMRATLAL BHAGWANDAS GANDHI 14 GULABPARK NEAR BASANT CINEMA CHEMBUR 400074 0000000000B9A0102806 30.00 5 ARVIND KUMAR DESAI H NO 2-1-563/2 NALLAKUNTA HYDERABAD 500044 0000000000B9A0106500 30.00 6 BIBISHAB S PATHAN 1005 DENA TOWER OPP ADUJAN PATIYA SURAT 395009 0000000000B9B0007570 144.00 7 BEENA DAVE 703 KRISHNA APT NEXT TO POISAR DEPOT OPP OUR LADY REMEDY SCHOOL S V ROAD, KANDIVILI (W) MUMBAI 400067 0000000000B9B0009430 30.00 8 BABULAL S LADHANI 9 ABDUL REHMAN STREET 3RD FLOOR ROOM NO 62 YUSUF BUILDING MUMBAI 400003 0000000000B9B0100587 30.00 9 BHAGWANDAS Z BAPHNA MAIN ROAD DAHANU DIST THANA W RLY MAHARASHTRA 401601 0000000000B9B0102431 48.00 10 BHARAT MOHANLAL VADALIA MAHADEVIA ROAD MANAVADAR GUJARAT 362630 0000000000B9B0103101 60.00 11 BHARATBHAI R PATEL 45 KRISHNA PARK SOC JASODA NAGAR RD NR GAUR NO KUVO PO GIDC VATVA AHMEDABAD 382445 0000000000B9B0103233 48.00 12 BHARATI PRAKASH HINDUJA 505 A NEEL KANTH 98 MARINE DRIVE P O BOX NO 2397 MUMBAI 400002 0000000000B9B0103411 60.00 13 BHASKAR SUBRAMANY FLAT NO 7 3RD FLOOR 41 SEA LAND CO OP HSG SOCIETY OPP HOTEL PRESIDENT CUFFE PARADE MUMBAI 400005 0000000000B9B0103985 96.00 14 BHASKER CHAMPAKLAL -

December, 2015

Regional Coopertion Newsletter – South Asia Regional Cooperation Newsletter- South Asia October- December, 2015 Editor Prof. P. K. Shajahan Ph.D. Guest Editor Prabhakar Jayaprakash 1 Regional Coopertion Newsletter – South Asia Regional Cooperation Newsletter – South Asia is an online quarterly newsletter published by the Inter- national Council on Social Welfare – South Asia Region. Currently, it is functioning from the base of the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai, India. The content of this newsletter may be freely reproduced or cited provided the source is acknowledged. The views expressed in this publication are those of the respective author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or position of ICSW. CONTENTS Editor’s note 01 Special article Sri Lanka: The Road to Truth, Justice, and Reconciliation 03 -Prabhakar Jayaprakash Articles The Ambitiousness of Jan Dhan Yojana 10 - Srishti Kochhar, Anmol Somanchi, and Vipul Vivek Myanmar: On Road to the Future 15 -Kaveri Commentaries Contextualizing Sri Lanka 19 - G.V.D Tilakasiri Masculinity of Nation States: The Case of Nepal 22 -Abhishek Tiwari News and Events 26 2 Regional Coopertion Newsletter – South Asia EDITOR’S NOTE Since the last few years, South Asian countries are said to be in a political transition. The end of civil war amidst criticism of widespread human rights violations followed by presidential elections in Sri Lanka two years ahead of its schedule brought surprise to the incumbent President Mahinda Rajapaksa with his erstwhile Minister of Health, Maithripala Sirisena fielded by United National Party (UNP)-led opposition coalition being elected to the top post. Pakistan has seen Nawaz Sharif, once on Political exile, returning to power for his third term in the 2013 presidential elections. -

Mumbai-Marooned.Pdf

Glossary AAI Airports Authority of India IFEJ International Federation of ACS Additional Chief Secretary Environmental Journalists AGNI Action for good Governance and IITM Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology Networking in India ILS Instrument Landing System AIR All India Radio IMD Indian Meteorological Department ALM Advanced Locality Management ISRO Indian Space Research Organisation ANM Auxiliary Nurse/Midwife KEM King Edward Memorial Hospital BCS Bombay Catholic Sabha MCGM/B Municipal Council of Greater Mumbai/ BEST Brihan Mumbai Electric Supply & Bombay Transport Undertaking. MCMT Mohalla Committee Movement Trust. BEAG Bombay Environmental Action Group MDMC Mumbai Disaster Management Committee BJP Bharatiya Janata Party MDMP Mumbai Disaster Management Plan BKC Bandra Kurla Complex. MoEF Ministry of Environment and Forests BMC Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation MHADA Maharashtra Housing and Area BNHS Bombay Natural History Society Development Authority BRIMSTOSWAD BrihanMumbai Storm MLA Member of Legislative Assembly Water Drain Project MMR Mumbai Metropolitan Region BWSL Bandra Worli Sea Link MMRDA Mumbai Metropolitan Region CAT Conservation Action Trust Development Authority CBD Central Business District. MbPT Mumbai Port Trust CBO Community Based Organizations MTNL Mahanagar Telephone Nigam Ltd. CCC Concerned Citizens’ Commission MSDP Mumbai Sewerage Disposal Project CEHAT Centre for Enquiry into Health and MSEB Maharashtra State Electricity Board Allied Themes MSRDC Maharashtra State Road Development CG Coast Guard Corporation -

SR NO First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio

SR NO First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 A SPRAKASH REDDY 25 A D REGIMENT C/O 56 APO AMBALA CANTT 133001 0000IN30047642435822 22.50 2 A THYAGRAJ 19 JAYA CHEDANAGAR CHEMBUR MUMBAI 400089 0000000000VQA0017773 135.00 3 A SRINIVAS FLAT NO 305 BUILDING NO 30 VSNL STAFF QTRS OSHIWARA JOGESHWARI MUMBAI 400102 0000IN30047641828243 1,800.00 4 A PURUSHOTHAM C/O SREE KRISHNA MURTY & SON MEDICAL STORES 9 10 32 D S TEMPLE STREET WARANGAL AP 506002 0000IN30102220028476 90.00 5 A VASUNDHARA 29-19-70 II FLR DORNAKAL ROAD VIJAYAWADA 520002 0000000000VQA0034395 405.00 6 A H SRINIVAS H NO 2-220, NEAR S B H, MADHURANAGAR, KAKINADA, 533004 0000IN30226910944446 112.50 7 A R BASHEER D. NO. 10-24-1038 JUMMA MASJID ROAD, BUNDER MANGALORE 575001 0000000000VQA0032687 135.00 8 A NATARAJAN ANUGRAHA 9 SUBADRAL STREET TRIPLICANE CHENNAI 600005 0000000000VQA0042317 135.00 9 A GAYATHRI BHASKARAAN 48/B16 GIRIAPPA ROAD T NAGAR CHENNAI 600017 0000000000VQA0041978 135.00 10 A VATSALA BHASKARAN 48/B16 GIRIAPPA ROAD T NAGAR CHENNAI 600017 0000000000VQA0041977 135.00 11 A DHEENADAYALAN 14 AND 15 BALASUBRAMANI STREET GAJAVINAYAGA CITY, VENKATAPURAM CHENNAI, TAMILNADU 600053 0000IN30154914678295 1,350.00 12 A AYINAN NO 34 JEEVANANDAM STREET VINAYAKAPURAM AMBATTUR CHENNAI 600053 0000000000VQA0042517 135.00 13 A RAJASHANMUGA SUNDARAM NO 5 THELUNGU STREET ORATHANADU POST AND TK THANJAVUR 614625 0000IN30177414782892 180.00 14 A PALANICHAMY 1 / 28B ANNA COLONY KONAR CHATRAM MALLIYAMPATTU POST TRICHY 620102 0000IN30108022454737 112.50 15 A Vasanthi W/o G -

(Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 1954 1 Dr. Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan BR TN Public Affairs Expired 2 Shri Chakravarti Rajagopalachari BR TN Public Affairs Expired 3 Dr. Chandrasekhara Raman BR TN Science & Eng. Expired Venkata 4 Shri Nand Lal Bose PV WB Art Expired 5 Dr. Satyendra Nath Bose PV WB Litt. & Edu. 6 Dr. Zakir Hussain PV AP Public Affairs Expired 7 Shri B.G. Kher PV MAH Public Affairs Expired 8 Shri V.K. Krishna Menon PV KER Public Affairs Expired 9 Shri Jigme Dorji Wangchuk PV BHU Public Affairs 10 Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha PB MAH Science & Eng. Expired 11 Dr. Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar PB UP Science & Eng. Expired 12 Shri Mahadeva Iyer Ganapati PB OR Civil Service 13 Dr. J.C. Ghosh PB WB Science & Eng. Expired 14 Shri Maithilisharan Gupta PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 15 Shri Radha Krishan Gupta PB DEL Civil Service Expired 16 Shri R.R. Handa PB PUN Civil Service Expired 17 Shri Amar Nath Jha PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 18 Shri Malihabadi Josh PB DEL Litt. & Edu. 19 Dr. Ajudhia Nath Khosla PB DEL Science & Eng. Expired 20 Shri K.S. Krishnan PB TN Science & Eng. Expired 21 Shri Moulana Hussain Madni PB PUN Litt. & Edu. Ahmed 22 Shri V.L. Mehta PB GUJ Public Affairs Expired 23 Shri Vallathol Narayana Menon PB KER Litt. & Edu. Expired Wednesday, July 22, 2009 Page 1 of 133 Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 24 Dr. -

Social Entrepreneurship Dr

Social Entrepreneurship Dr. Jack M. Wilson, Distinguished Professor of Higher Education, Emerging Technologies, and Innovation Entrepreneurship: © 2012 ff -Jack M. Wilson Distinguished Professor Social Entrepreneurship 1 Social Entrepreneurs -”No margin? No mission!” • Social Entrepreneurs use many of the same techniques as the other forms. • The key difference is that their primary goal is to meet social needs rather than financial profit. • However, they do need to make the enterprise financially sustainable and thus they have to attend to revenues, expenses and profits like anyone else. – If there is no margin (profit or surplus), then there is no mission. • They can organize as a non-profit and support the enterprise, at least in part, through charitable donations to the mission. Mother Teresa organized her enterprise in this way. • They can also organize as a for-profit as did Harish Hande, Muhammad Yunas, and d-Light. Entrepreneurship: © 2012 ff -Jack M. Wilson Distinguished Professor Social Entrepreneurship 2 Large Corporations • Large Corporations will often become involved in some kinds of Social Enterprise. • They often do this through a sense of corporate responsibility toward the communities in which they operate. • Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) has become an important part of their operation and is often required by communities as part of their license to operate. • The triple bottom line encourages companies to focus on more than the bottom line of profits. It includes – 1. Social, – 2. Environmental, and – 3) Financial results. • Engaging with the community can sometimes be challenging. In many cases the company may be engaging with individuals who are leading bitter protests towards the company. -

SOCIAL ENTREPRENEUR of the YEAR INDIA 2011 Social Entrepreneurship for Inclusive Growth

SOCIAL ENTREPRENEUR OF THE YEAR INDIA 2011 Social Entrepreneurship for Inclusive Growth Introduction Professor Klaus Schwab founder of World Economic Forum along with his wife Hilde founded the Schwab Foundation for Social Entrepreneurship in 1998, with the purpose to promote entrepreneurial solutions and social commitment with a clear impact at the grassroots level. The World Economic Forum and the Schwab Foundation work in close partnership to provide social entrepreneurs Prof. Klaus Schwab and Hilde Schwab with unique platforms at the regional and global levels to showcase their important role and work in today’s society. Jubilant Bhartia Foundation, the social wing of the Jubilant Bhartia Group, was established in 2007. As a part of the Jubilant Bhartia Group, we focus on conceptualizing and implementing the Corporate Social Responsibility initiatives for the group. The foundation’s objectives include various community development work, health care, culture and sports, environment preservation initiative, vocational S S Bhartia and H S Bhartia training, women empowerment and educational activities. 1 The Importance of Social Entrepreneurship Social entrepreneurship is about applying practical, innovative and sustainable approaches to benefi t society, with an emphasis on the marginalized and the socioeconomically disadvantaged. Social entrepreneurs drive social innovation and transformation across all diff erent fi elds and sectors, including but not limited to health, education, environment and enterprise development. They pursue their social mission with entrepreneurial zeal, business methods and the courage to overcome traditional practices. 2 Foreword The Schwab Foundation for Social Entrepreneurship and the Jubilant Bhartia Foundation are dedicated to promoting social innovation in India. In recognizing social entrepreneurs who address the needs of under-served communities in both scalable and sustainable ways, we aim to make inclusive growth in the country a reality. -

Main Voter List 08.01.2018.Pdf

Sl.NO ADM.NO NAME SO_DO_WO ADD1_R ADD2_R CITY_R STATE TEL_R MOBILE 61-B, Abul Fazal Apartments 22, Vasundhara 1 1150 ACHARJEE,AMITAVA S/o Shri Sudhamay Acharjee Enclave Delhi-110 096 Delhi 22620723 9312282751 22752142,22794 2 0181 ADHYARU,YASHANK S/o Shri Pravin K. Adhyaru 295, Supreme Enclave, Tower No.3, Mayur Vihar Phase-I Delhi-110 091 Delhi 745 9810813583 3 0155 AELTEMESH REIN S/o Late Shri M. Rein 107, Natraj Apartments 67, I.P. Extension Delhi-110 092 Delhi 9810214464 4 1298 AGARWAL,ALOK KRISHNA S/o Late Shri K.C. Agarwal A-56, Gulmohar Park New Delhi-110 049 Delhi 26851313 AGARWAL,DARSHANA 5 1337 (MRS.) (Faizi) W/o Shri O.P. Faizi Flat No. 258, Kailash Hills New Delhi-110 065 Delhi 51621300 6 0317 AGARWAL,MAM CHANDRA S/o Shri Ram Sharan Das Flat No.1133, Sector-29, Noida-201 301 Uttar Pradesh 0120-2453952 7 1427 AGARWAL,MOHAN BABU S/o Dr. C.B. Agarwal H.No. 78, Sukhdev Vihar New Delhi-110 025 Delhi 26919586 8 1021 AGARWAL,NEETA (MRS.) W/o Shri K.C. Agarwal B-608, Anand Lok Society Mayur Vihar Phase-I Delhi-110 091 Delhi 9312059240 9810139122 9 0687 AGARWAL,RAJEEV S/o Shri R.C. Agarwal 244, Bharat Apartment Sector-13, Rohini Delhi-110 085 Delhi 27554674 9810028877 11 1400 AGARWAL,S.K. S/o Shri Kishan Lal 78, Kirpal Apartments 44, I.P. Extension, Patparganj Delhi-110 092 Delhi 22721132 12 0933 AGARWAL,SUNIL KUMAR S/o Murlidhar Agarwal WB-106, Shakarpur, Delhi 9868036752 13 1199 AGARWAL,SURESH KUMAR S/o Shri Narain Dass B-28, Sector-53 Noida, (UP) Uttar Pradesh0120-2583477 9818791243 15 0242 AGGARWAL,ARUN S/o Shri Uma Shankar Agarwal Flat No.26, Trilok Apartments Plot No.85, Patparganj Delhi-110 092 Delhi 22433988 16 0194 AGGARWAL,MRIDUL (MRS.) W/o Shri Rajesh Aggarwal Flat No.214, Supreme Enclave Mayur Vihar Phase-I, Delhi-110 091 Delhi 22795565 17 0484 AGGARWAL,PRADEEP S/o Late R.P. -

Date of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) 09-AUG-2018

Note: This sheet is applicable for uploading the particulars related to the unclaimed and unpaid amount pending with company. Make sure that the details are in accordance with the information already provided in e-form IEPF-2 CIN/BCIN L24110MH1956PLC010806 Prefill Company/Bank Name CLARIANT CHEMICALS (INDIA) LIMITED Date Of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) 09-AUG-2018 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 3803100.00 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0.00 Sum of matured deposit 0.00 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0.00 Sum of matured debentures 0.00 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0.00 Sum of application money due for refund 0.00 Redemption amount of preference shares 0.00 Sales proceed for fractional shares 0.00 Validate Clear Proposed Date of Investor First Investor Middle Investor Last Father/Husband Father/Husband Father/Husband Last DP Id-Client Id- Amount Address Country State District Pin Code Folio Number Investment Type transfer to IEPF Name Name Name First Name Middle Name Name Account Number transferred (DD-MON-YYYY) THOLUR P O PARAPPUR DIST CLAR000000000A00 Amount for unclaimed and A J DANIEL AJJOHN INDIA Kerala 680552 5932.50 02-Oct-2019 TRICHUR KERALA TRICHUR 3572 unpaid dividend INDAS SECURITIES LIMITED 101 CLAR000000000A00 Amount for unclaimed and A J SEBASTIAN AVJOSEPH PIONEER TOWERS MARINE DRIVE INDIA Kerala 682031 192.50 02-Oct-2019 3813 unpaid dividend COCHIN ERNAKULAM RAMACHANDRA 23/10 GANGADHARA CHETTY CLAR000000000A00 Amount for unclaimed and A K ACCHANNA INDIA Karnataka 560042 3500.00 02-Oct-2019 PRABHU