Engst CU.Pdf (292.8Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tompkins County HM Final Draft 01-16-14.Pdf

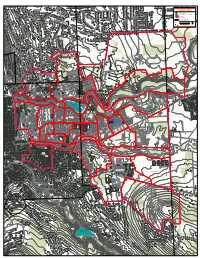

This Multi-Jurisdictional All-Hazard Mitigation Plan Update has been completed by Barton & Loguidice, P.C., under the direction and support of the Tompkins County Planning Department. All jurisdictions within the County participated in this update process. A special thanks to the representatives and various project team members, whose countless time and effort on this project was instrumental in putting together a concise and meaningful document. Tompkins County Planning Department 121 East Court Street Ithaca, New York 14850 Tompkins County Department of Emergency Response Emergency Response Center 92 Brown Road Ithaca, New York 14850 Tompkins County Multi-Jurisdictional All-Hazard Mitigation Plan Table of Contents Section Page Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................1 1.0 Introduction ........................................................................................................................3 1.1 Background ..............................................................................................................3 1.2 Plan Purpose.............................................................................................................4 1.3 Planning Participants ...............................................................................................6 1.4 Hazard Mitigation Planning Process ........................................................................8 2.0 Tompkins County Profile ..................................................................................................9 -

32026062-MIT.Pdf

K.'-.- A, N E W Q UA D R A N G L E F O R C O R N E L L U N I V E R S I T Y A Thesis.submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement s for the degree of Master of Architec ture at the Massachusetts Inst itute of Technology August 15, 1957 Dean Pie tro Bel lus ch Dean of the School of Archi tecture and P lanning Professor000..eO0 Lawrence*e. *90; * 9B. Anderson Head oythe Departmen ty6 Arc,hi tecture Earl Robert"'F a's burgh Bachelor of Architecture, Cornell University,9 June 1954 323 Westgate West Cambridge 39, Mass. August 14, 1957 Dean Pietro Belluschi School of Architecture and Planning Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge 39, Massachusetts Dear De-an Belluschi, In partial fulfillment- of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture, I should like to submitimy thesis entitled, "A New Quad- rangle for Cornell University". Sincer y yours, -"!> / /Z /-7xIe~ Earl Robert Fla'nsburgh gr11 D E D I C A T I O N To my wife, Polly A C K N O W L E D G E M E N T S The development of this thesis has been aided by many members of the s taff at both M.I.T. &nd Cornell University. W ithou t their able guidance and generous assistance this t hesis would not have been possible. I would li ke to take this opportunity to acknowledge the help of the following: At M. I. T. -

UC Santa Barbara Other Recent Work

UC Santa Barbara Other Recent Work Title Geopolitics, History, and International Relations Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/29z457nf Author Robinson, William I. Publication Date 2009 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE CONTEMPORARY SCIENCE ASSOCIATION • NEW YORK Geopolitics, History, and International Relations VOLUME 1(2) • 2009 ADDLETON ACADEMIC PUBLISHERS • NEW YORK Geopolitics, History, and International Relations 1(2) 2009 An international peer-reviewed academic journal Copyright © 2009 by the Contemporary Science Association, New York Geopolitics, History, and International Relations seeks to explore the theoretical implications of contemporary geopolitics with particular reference to territorial problems and issues of state sovereignty, and publishes papers on contemporary world politics and the global political economy from a variety of methodologies and approaches. Interdisciplinary and wide-ranging in scope, Geopolitics, History, and International Relations also provides a forum for discussion on the latest developments in the theory of international relations and aims to promote an understanding of the breadth, depth and policy relevance of international history. Its purpose is to stimulate and disseminate theory-aware research and scholarship in international relations throughout the international academic community. Geopolitics, History, and International Relations offers important original contributions by outstanding scholars and has the potential to become one of the leading journals in the field, embracing all aspects of the history of relations between states and societies. Journal ranking: A on a seven-point scale (A+, A, B+, B, C+, C, D). Geopolitics, History, and International Relations is published twice a year by Addleton Academic Publishers, 30-18 50th Street, Woodside, New York, 11377. -

Cornell Alumni News

Cornell Alumni News Volume 46, Number 22 May I 5, I 944 Price 20 Cents Ezra Cornell at Age of Twenty-one (See First Page Inside) Class Reunions Will 25e Different This Year! While the War lasts, Bonded Reunions will take the place of the usual class pilgrimages to Ithaca in June. But when the War is won, all Classes will come back to register again in Barton Hall for a mammoth Victory Homecoming and to celebrate Cornell's Seventy-fifth Anniversary. Help Your Class Celebrate Its Bonded Reunion The Plan is Simple—Instead of coming to your Class Reunion in Ithaca this June, use the money your trip would cost to purchase Series F War Savings Bonds in the name of "Cornell University, A Corporation, Ithaca, N. Y." Series F Bonds of $25 denomination cost $18.50 at any bank or post office. The Bonds you send will be credited to your Class in the 1943-44 Alumni Fund, which closes June 30. They will release cash to help Cornell through the difficult war year ahead. By your participation in Bonded Reunions: America's War Effort Is Speeded Cornell's War Effort Is Aided Transportation Loads Are Eased Campus Facilities ^re Saved Your Class Fund Is Increased Cornell's War-to-peace Conversion Your Money Does Double Duty Is Assured Send your Bonded Reunion War Bonds to Cornell Alumni Fund Council, 3 East Avenue, Ithaca, N. Y. Cornell Association of Class Secretaries Please mention the CORNELL ALUMNI NEWS Volume 46, Number 22 May 15, 1944 Price, 20 Cents CORNELL ALUMNI NEWS Subscription price $4 a year. -

This Document Is from the Cornell University Library's Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections Located in the Carl A

This document is from the Cornell University Library's Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections located in the Carl A. Kroch Library. If you have questions regarding this document or the information it contains, contact us at the phone number or e-mail listed below. Our website also contains research information and answers to frequently asked questions. http://rmc.library.cornell.edu Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections 2B Carl A. Kroch Library Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853 Phone: (607) 255-3530 Fax: (607) 255-9524 E-mail: [email protected] I,:RESTRICTED 4 / 2 / 186 6 ,___ - ti C.U. Vice President for Academic Programs. Larry I. Palmer Records, 1967-1987. Guide +·:--· ]_,:::,n FI l··-1 F''l·-1 1::·,::-.1 .i".-iE::I? ,, l...(·,l?l'(f i:::: ,:::, ,--- n ,:-:-:· l l !___! n :i. '-/ (-:-~ ,--- ,,_ :i. -!:. / .. \,' :i. c: (-:-:, i::· ,-- c• .-;,. :i. d c• n t ·f o ,-- - t, c: .:,\ cl ,:-:-:· 1T1 :i. c: F' ,--· ,:::, (_:_1 ,--- <':\ rn ~::- • I... E•. i--· ,--· ::---- l .. i::· .:,, 1 rn (-:-:· ,--· ,... ,:-:· c: c:, ,.-- d ·;;,. ,, :I. ·:_,, (. )' ·--- :I. '? b ·7 .. -'18 c:ub:i. c: --rt .. C) ,--· c_1 "' n :i. z .,,-._ t :i. ,:::, n :: ,::-, J p h .,,,_ b ,:,.:, t :i. c: .,,,. l b >-' ·:::- u b .:i c· c: t VJ :i. t h :i. n -r :i. !::- c: ,,'< 1 >,.- <-:-:· ,,,. ,,. .. !?(-:-:· ,:::,:::,,--·cl ·:::- ·f 1-··orn :I.·:_;;(, 7 to :I. •/:::J,·:J, ,,'< 1-·-,:-:;· ·f 1---01n -!:. h,:-:-:· (J·f ·f :i. c:,:-:,, c:,·f '.,,' :i. c:<-:, F' 1-··o·-./c:,·,;;. t 1--· ,:-:-:· c:,:::, i--·cJ ;,=. ·f i-- om J.985 to :J.986 are from the off:i.c:e of the V:i.c:e President for Ac:aclem:i.c: Programs Tho:-:-:• n.,-,-._m,:-:-:· c: h-:':-..n <:_:_! ,:-:-:· d :i.d n ,:::, t i--·,:-:-;·f l <-:-:•c: t .,,._n / c: h.,,,nc.1<-:-; :i.n p,:-:-:•1"sonn ,:-:,l DI" !''(-".··,=,.pan-,,,. -

Tompkins County Public Library Assigned Branch: Ithaca - Tompkins County Public Library (TCPL) Collection: Local History (LH)

TOMPKINS COUNTY Navigating A Sea Of Resources PUBLIC LIBRARY Title: The first hundred years : a history of the Cornell Public Library, Ithaca, New York, and the Cornell Library Association, 1864-1964. Author: Call number: LH-CASE 027.409 Peer Publisher: [Ithaca, N.Y.?] : [s.n.] 1969. Owner: Ithaca - Tompkins County Public Library Assigned Branch: Ithaca - Tompkins County Public Library (TCPL) Collection: Local History (LH) Material type: Book Number of pages: 1 30 pages THE FIRST HUNDRED YEARS A HISTORY OF THE CORNELL PUBLIC LIBRARY Ithaca, New York and the CORNELL LIBRARY ASSOCIATION 1864 - 1964 by Sherman Peer THE AUTHOR It's good to think of the new library so well organized and increasing in service. I am happy to have lived to see it functioning fully and so well received by the people of Tompkins County. Letter from Sherman Peer, dated February 2?, 19^9, to Mrs. John Vandervort, chairman of the trustees of the Tompkins County Public Library. Sherman Peer searched the records of the Cornell Library Association, many other written sources, and his own rich memories to write this history. A prominent Ithaca attorney who enjoyed writing and story-telling, Mr. Peer completed his work on it in 1964, when he was 81 years old. The epilogue was written by Mary Tibbets Freeman, and the manuscript was prepared for presentation at the formal dedication of the Tompkins County Library Building on April 20, 19&9. The historian also shaped the library's history by assisting in its successful rebirth as a public institution in its second century. He was convinced that the Cornell Public Library, operated since 1866 by the private Cornell Library Associa tion founded by Ezra Cornell, needed public funds for a new building and continuing support. -

Campus Landscape Notebook

CAMPUS LANDSCAPE NOTEBOOK Campus Planning Office May 2005 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Campus Landscape Notebook, 2005, was produced in the Cornell Campus Planning Office under the direction of the University Planner, Minakshi Amundsen. John Ullberg, Landscape Architect, composed text, provided photographs and many graphics. Illiana Ivanova, graphic designer, composed and formatted content and created graphics as well. Andrew Eastlick produced campus base maps. Craig Eagleson provided both technical support and graphic advice. Many others have contributed to the project by editing, researching and advising. Among them are Laurene Gilbert, Ian Colgan, Jim Constantin, Dennis Osika, Frank Popowitch, Peter Karp, Don Rakow, Helen Baker, Craig Eagleson, Phil Cox, Jim Gibbs and Kent Hubbell. Photo Credits p2- Libe Slope White Oak- Robert Barker, Cornell University Photography p5- Aerial view of campus- Kucera International, Inc. All other aerial views except otherwise noted- Jon Reis (www.jonreis.com) CAMPUS LANDSCAPE NOTEBOOK INTRODUCTION S E C T I O N 1 THE CAMPUS LANDSCAPE, PAST TO PRESENT ORIGINS. 9 HISTORY AND EVOLUTION. 11 CHRONOLOGY . 21 FUTURE . 23 THE CAMPUS EXPERIENCE . 25 S E C T I O N 2 LANDSCAPE SYSTEMS AT CORNELL PHYSIOGRAPHY . 31 THE OPEN SPACE SYSTEM . .33 THE WORKING LANDSCAPE. .35 LINKS. .37 GEOMETRY. 39 ARCHITECTURE. .41 WAYFINDING. .45 VIEWS. 47 LANDSCAPE VOCABULARY. 49 LANDMARKS. .55 SUMMARY. .59 INTRODUCTION Landscape has meaning. The quality and meaning of the living and learning experience at Cornell are fundamentally related to the quality of the campus environment. For six years a political prisoner of the communist By any measure Cornell’s is a remarkable landscape - deep wild gorges, government in Laos, the former Laotian official said lakes, cascades, noble buildings set among noble trees, expansive views he was sustained by memories of Cornell Univer- all contribute to a special presence that sets Cornell apart from its peers. -

Campus Map a K L Ar E Th P L R D T No C E En E Riv N X R D a I Od Hl a L O Cornell Buildings

E V I R D N O T E E E V R I T W REMINGTON ROAD R S D N I E T W T N TUARY DRIVE I OUR E NC A SA E E R SIMSBURY DRIV W R E Y T Y D S T N O L A E N R I B R D U R I M SPRUCE LANE V E MEADOWLANERK ROAD T HE ETOPHER LANE P CHRISTRE AR KW A NE Y CAMPUS MAP A K L AR E TH P L R D T NO C E EN E RIV N X R D A I OD HL A L O CORNELL BUILDINGS C W S I H G I S RC H N BI L R E A WOOD DRIV A BIRCH E N L D E A H A N P E O O S T R I N E BUILDINGS OF OTHER DESIGNATION E X T N O E R N N R B E I A P T L L H S D A I A N R R H M E A I H M V P M C ADINAL DRIVE C CARO T E O K N COMSTREETOCK ROAD E CMP ZONES RO R S A T D R R O E E A C E D A T MORE DRIVE L O SYCA P CMP PRECINCTS N D E O E A V A PLACE O S I LI V E W E R N E IV D 2566 R U D N MUNICIPAL BOUNDARIES I D Rhodes House T E ROCKY LANE E P E O R SA T I O ES N T W OR C F AT MA R 20' TOPOGRAPHIC CONTOURS H NO A R I H E STR I R E R G IN ET H E B L C A IR C N LE RIVE E MAPLACEEWOOD D N D 0 250 500 750 R O A D Feet N O R T H E V I R © Campus Planning Office D January 2014 M E OAD L R A ODS BIRCHWOOD DRIVE O S W T KLINE E E Robin Hill Carriage House R T S Y KAY STREET SPUR A K M C I D E A C Y A W N Y U A A U L G Y G A R H R AN Robin Hill A E S H O H HANSHAW ROAD AW P R E A M D O 2514 A AD I D M A G R A O H K H R T R P S I D O R R N A O T A D L A P D U T S A E F O R R E E C S H E CIR B A RK L R R PA A O C D A A K D S G A S U T T Y R O A C C E N E D E T A A O A R AY V H HW E RT N Dyce Lab NO T U Storage I W E E AT STREET S RO 2810E T U P L Dyce Lab A F N Garage D O Dyce Lab R O 2810A A Garden Shed D 2810N Dyce Lab -

Affective Communities in Late-Medieval Iberian Literature

AFFECTIVE COMMUNITIES IN LATE-MEDIEVAL IBERIAN LITERATURE A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Henry Samuel Berlin August 2011 © 2011 Henry Samuel Berlin AFFECTIVE COMMUNITIES IN LATE-MEDIEVAL IBERIAN LITERATURE Henry Samuel Berlin, Ph.D. Cornell University 2011 My dissertation offers a new account of the explosion of sentimental literature in fifteenth-century Iberia and, at the same time, suggests a new way of reading that literature. Through the concept of the affective community, which suggests that political, religious, and literary communities (genres) are held together and shaped not so much by shared emotion as by a shared ethical attitude toward emotion, I analyze exemplary works of the principal genres involved in this explosion: cancionero poetry and sentimental fiction. Other important genres such as the chronicle and chivalric fiction also play key roles in my analysis, and my approach throughout is comparative, dealing substantially with works not only from Castile, but also from the kingdoms of Portugal and Aragon. The most important texts in the dissertation are Pedro de Corral‘s Crónica sarracina (ca. 1430); Pedro, Constable of Portugal‘s Sátira de felice e infelice vida (ca. 1450); and the poetry of Ausiàs March (ca. 1397-1459). However, I also discuss moral, theological, and political treatises by crucial figures such as Alonso de Cartagena (1384-1456); Alfonso de Madrigal, el Tostado (1410-1455); Rodrigo Sánchez de Arévalo (ca. 1404-1470); Diego de Valera (1412-1488); Duarte I of Portugal (1391-1438); and the Infante Pedro, Duke of Coimbra (1392-1449). -

"True and Firm." Biography of Ezra Cornell, Founder of the Cornell

ifflmortam t J. REV. R. J. COTTER, D. 0. BIOGRAPHY EZRA CORNELL, FOUNDER OF THE CORNELL UNIVERSITY. 'gilml NEW YORK : A. S. BARNES & COMPANY. 1884. COPYRIGHT BY A. S. BARNES & CO. 1884 I J CO MY DEAR MOTHER, WHOSE AFFECTIONATE DEVOTION, FRUGAL ECONOMY, WISE COUNSEL, PATIENT FIDELITY AND CHEERFUL BEARING CONTRIBUTED SO MUCH TO THE ACHIEVEMENTS RECORDED HEREIN, THIS VOLUME IS DEDICATED AS A TRIBUTE OF FILIAL GRATITUDE AND REVERENCE. PREFACE. FOR several years it has been the author's de- sire that a suitable biography of the FOUNDER OF THE CORNELL UNIVERSITY should be prepared by another, whose cultured pen would invest the work with that degree of interest to which the subject is so worthily entitled. Exacting duties have, however, delayed such an undertaking, and still prevent any reasonable promise of its early consummation. Mainly for the purpose of placing the material in form for safe preservation for future use, this simple record of the leading incidents of his earnest life and untiring labors has been pre- pared, which, it is hoped, may hereafter serve as a text-book of facts requisite for the more inter- esting treatment of the subject by other and abler hands. Prepared originally for private use, it is realized that the work is deficient of any literary and that merit which would justify its publication, vi PREFACE. course has finally been taken only at the urgent solicitation of interested friends. Time has already largely depleted the ranks of those familiar with the early history of the tele- graph enterprise in America, and but few now re- main with us who participated in the pioneer work with which the subject of this sketch was so in- timately associated. -

Narrative Section of a Successful Application

Narrative Section of a Successful Application The attached document contains the grant narrative and selected portions of a previously funded grant application. It is not intended to serve as a model, but to give you a sense of how a successful application may be crafted. Every successful application is different, and each applicant is urged to prepare a proposal that reflects its unique project and aspirations. Prospective applicants should consult the Office of Digital Humanities program application guidelines at http://www.neh.gov/grants/odh/humanities-open-book-program for instructions. Applicants are also strongly encouraged to consult with the NEH Office of Digital Humanities staff well before a grant deadline. Note: The attachment only contains the grant narrative and selected portions, not the entire funded application. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. Project Title: Humanities Open Book Program – Cornell University Institution: Cornell University Project Director: Dean J. Smith Grant Program: Humanities Open Book Program 1. Table of Contents 2. List of Participants ...................................................................................................... 2-1 3. Abstract ........................................................................................................................... 3-1 4. Narrative a. Intellectual Significance of -

Alumni Magazine C2-C4camjf07 12/21/06 2:50 PM Page C2 001-001Camjf07toc 12/21/06 1:39 PM Page 1

c1-c1CAMJF07 12/22/06 1:58 PM Page c1 January/February 2007 $6.00 alumni magazine c2-c4CAMJF07 12/21/06 2:50 PM Page c2 001-001CAMJF07toc 12/21/06 1:39 PM Page 1 Contents JANUARY / FEBRUARY 2007 VOLUME 109 NUMBER 4 alumni magazine Features 52 2 From David Skorton Residence life 4 Correspondence Under the hood 8 From the Hill Remembering “Superman.” Plus: Peres lectures, seven figures for Lehman, a time capsule discovered, and a piece of Poe’s coffin. 12 Sports Small players, big win 16 Authors 40 Pynchon goes Against the Day 40 Going the Distance 35 Camps DAVID DUDLEY For three years, Cornell astronomers have been overseeing Spirit 38 Wines of the Finger Lakes and Opportunity,the plucky pair of Mars rovers that have far out- 2005 Atwater Estate Vineyards lived their expected lifespans.As the mission goes on (and on), Vidal Blanc Associate Professor Jim Bell has published Postcards from Mars,a striking collection of snapshots from the Red Planet. 58 Classifieds & Cornellians in Business 112 46 Happy Birthday, Ezra 61 Alma Matters BETH SAULNIER As the University celebrates the 200th birthday of its founder on 64 Class Notes January 11, we ask: who was Ezra Cornell? A look at the humble Quaker farm boy who suffered countless financial reversals before 104 Alumni Deaths he made his fortune in the telegraph industry—and promptly gave it away. 112 Cornelliana What’s your Ezra I.Q.? 52 Ultra Man BRAD HERZOG ’90 18 Currents Every morning at 3:30, Mike Trevino ’95 ANATOMY OF A CAMPAIGN | Aiming for $4 billion cycles a fifty-mile loop—just for practice.