Kantian Themes in the Work of Michael Wyschogrod

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teaching Jewish-Christian Relations in the University Classroom

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 307 180 SO 019 860 AUTHOR Shermis, Michael, EC. TITLE Teaching Jewish-Christian Relations in the University Classroom. PUB DATE 88 NOTE 127p. 7UB TYPE Collected Works - Serials (022) JOURNAL CIT Shofar; v6 n4 Sum 1988 EDRS PRICE MF01/PC06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Anti Semitism; Biblical Literature; Biographies; *Christianity; *Cultural Exchange; *Cultural Interrelationships; Educational Resources; Higher Education; *Judaism IDENTIFIERS Israel; Jewish Culture; *Jewish Studies; WiesP1 (Eli) ABSTRACT This special issue on "Teaching Jewish-Christian Relations in the University Classroom" is meaAt to be a resource for those involved in Jewish studies and who teach about Jewish-Christian relations. It offers an introduction to the topics of the Jewish-Christian encounter, Israel, anti-Semitism, Christian Scriptures, the works of Elie Wiesel, and available educational resources, all in light of the Jewish-Christian dialogue in institutions of higher learning. Carl Evans presents a syllabus for a course in which students are required to converse with local clergy in order to explain the Jewish-Christian dialogue at the grass-roots level. This technique helps students develop mature ways of thinking on a personal, social, and religious level. Robert Everett and Bruce Bramlett discuss Israel's problematic existence, raising numerous points that can lead to effective classroom discussions. Alan Davies describes his, course on anti-Semitism and presents several practical suggestions and instrumental techniques. John Roth offers a short biography of Elie Wiesel's J.ife, his writings, and his paradoxes. Norman Beck provides a model of how a Christian teaches the Christian Scriptures, offering guidelines that are highly supportive of and sympathetic to the Jewish-Christian dialogue. -

Prof. David Johnson Prof. Meir Soloveichik Syllabus: PHI 4931H Seminar: Metaphysics of Judaism Spring 2021

1 Prof. David Johnson Prof. Meir Soloveichik Syllabus: PHI 4931H Seminar: Metaphysics of Judaism Spring 2021 Goals of Seminar: Using medieval and modern philosophical sources, we will rigorously and extensively examine traditional Judaism’s philosophical and theological views on the nature and attributes of God. For centuries, Jewish philosophers, theologians and mystics have pondered biblical passages that speak of complex subjects such as: God’s love for Abraham and his children Israel; God dwelling within the tabernacle, and the Temple in Jerusalem; God’s foreknowledge of all human events, but also His anger at Israel’s sin, His regret following sin and His forgiveness following this anger. Maimonides, famously, read these verses through the lens of his own philosophical approach, seeking as much as possible to reduce any true analogy between God’s attributes (such as knowledge and love) and similarly named attributes of human beings. Describing biblical language about God as referring to either “negative attributes” or “attributes of action,” he insisted that any other approach would embody an assault on the doctrines of God’s perfection and noncorporeality. Maimonides’s philosophy does not embody the totality of Jewish thought. From Judah Halevi before Maimonides, to Nahmanides after, this approach was criticized as irreconcilable with biblical language and with Talmudic theology. Meanwhile, in the Christian world, Thomas Aquinas seriously engaged Maimonides’s writings and responded to them in a way that can be deeply instructive to Jewish students of philosophy. Centuries later, Michael Wyschogrod, influenced by the writings of Protestant theologian Karl Barth, offered his own critique of Maimonides. -

Article{Goldman-Kosher.By.Design, Author = {David P

@article{goldman-kosher.by.design, author = {David P. Goldman}, title = {Kosher by Design}, journal = {Tablet Magazine}, month = {Sept 14,}, year = {2010}, note = {goldman_2010.09.14_kosher.by.design_a.txt} } # [A few de!nitions] Ashkenazic Hazzanim = traditional (European Orthodox) Musicians. Some Examples: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yHGJSCOwJD8&feature=related http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ivB_0cSJguY&feature=related Chabad = orthodox Jewish sect, devoted to reconversion of Jews Dasein = Lit. 'being-there', authentic existence for a human being HaKodesh BaruchHu = '"e Holy One (Blessed be He)' Hatzlacha = Good luck! Torah im Derech Eretz = Being both Jewish and part of the world ahavos Hashem = the love of God ahavos Israel = the love of Israel (one's fellow Jews) ahavos Torah = the love of the Torah brit milah = circumcision ceremony daven = to pray davening = praying derekh eretz = 'ways of the world' g'mar chatima tova = 'May you be sealed in the Book of Life', i.e., greeting for the Day of Atonement goy = Gentile, non-Jew goyishe naches = Gentile pride and satisfaction kashrut = Jewish dietary law kol hakavod = 'way to go' mitzvah = commandment in the Torah mitzvot = plural of mitzvah oy vey zmir = 'oh gosh' shaila = what a disciple asks a sage shekhinah = glory of God (such as described at the end of Exodus) sine qua non = 'without which there is non' tallit = Jewish prayer shawl te!lah = ritual prayers teshuva = repentance tzadakah = giving charity # [On the author] David P. Goldman is a senior editor at First "ings magazine and the ``Spengler'' columnist for Asia Times Online. # [Text begin] ``Dad,'' insisted my younger daughter, ``we really must do something about this.'' I was about to get the sort of talking-to we dreaded from our parents and dread even more from our children. -

Hermann Cohen and Michael Wyschogrod

REASON, REVELATION, AND ELECTION: HERMANN COHEN AND MICHAEL WYSCHOGROD Samuel Hayim Brody Abstract The concept of election has posed challenges to Jewish thought when it has taken its most explicitly rationalist forms. Election doubly offends philosophy: first by claiming that God acted in history, and second by claiming that this action singled out a particular people, rather than the whole human race, for a special relationship. Here I examine two modern thinkers, Hermann Cohen and Michael Wyschogrod, in order to demonstrate the radical difference their philosophical starting points (Kant and Heidegger, respectively) make for their understandings of election. However, there are also significant commonalities between them, and I claim that exploring these reveals their most interesting difference to be located in an unexpected place: over the nature of worthy objects of love. Keywords: Hermann Cohen, Michael Wyschogrod, Election, Philosophy, Kant, Heidegger, neo-Kantianism, ethical monotheism, David Novak, love. It is well known how even in our days cosmopolitanism is felt to be in lively opposition to the consciousness of one’s own nationality. How incomprehensible the origin of Messianism in the midst of a national consciousness must appear to us, inasmuch as it had to think and to feel the “election” of Israel as a singling out for the worship of God. - Hermann Cohen …No generalized philosophy of religious ‘man’ can adequately serve as propaedeutic to the faith of Israel. With the election of Abraham, a series of events is set in motion which, in a sense, shatters the unity of the human race…The election of Israel cannot be digested by any philosophy nor, for that matter, can any philosophy lay the ground for such an event. -

God's Beloved: a Defense of Chosenness

God’s Beloved: A Defense of Chosenness eir oloveichik ne of Judaism’s central premises is that God has a unique love for O the Jewish people, in the merit of its ancestor Abraham, whom God loved millennia ago. is notion may make many readers uncomfortable, as they may feel that a righteous God would love all human beings, and therefore all peoples, equally and in the same way. Nevertheless, the notion of God’s special love for Israel must be stated and understood, for without it one cannot comprehend much that is unique about Judaism’s moral vision. ere is no question that to speak of the Jews as a “chosen nation” is to speak of their being charged with a universal mission: Communicating the monotheistic idea and a set of moral ideals to humanity. In designating Israel as a “nation of kingly priests” and a “light unto nations,”1 God, ac- cording to the medieval exegete Obadiah Seforno, commanded the Jews to “teach to the entire human race, so that they may call in the name of God, to serve him together.”2 It is, however, often overlooked that the doctrine of Israel’s chosenness also contains a strongly particularistic idea: at God chose the Jewish / • people for this mission out of his love for their forefather Abraham. e book of Deuteronomy is unambiguous on this point: To you it was shown, so that you might know that the Eternal, he is God; there is none else beside him.… And because he loved your fathers, therefore he chose their seed after them, and brought you out in his sight with his mighty power out of Egypt ; to drive out nations from before you, greater and mightier than you are, to bring you in, to give you their land for an inheritance, as it is this day.3 e Tora later states that God’s love for Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob was then bestowed upon their children: e Eternal did not set his love upon you, nor choose you, because you were more in number than any people; for you were the fewest of all peo- ples. -

Barth, Israel and Jesus: Karl Barth’S Theology of Israel

BARTH, ISRAEL AND JESUS: KARL BARTH’S THEOLOGY OF ISRAEL ‘Your name will be Israel, because you have struggled with God and with men and have overcome.’ ———Gen 32:28 Barth, Israel and Jesus: Karl Barth’s Theology of Israel MARK R. LINDSAY Centre for the Study of Jewish-Christian Relations, Cambridge Fellow, Department of History, University of Melbourne Contents Preface ........................................................................................ vii Acknowledgments ........................................................................ xi List of Abbreviations ................................................................... xii Introduction ......................................... 1 1. Jewish-Christian Relations Since 1945 ................................. 7 Obstacles Along the Way ....................................... 10 Confessional mea culpas: Church statements addressing the Holocaust ....................................... 13 Nostre Aetate ....................................... 14 The 1980 Rhineland Synod ....................................... 18 Conclusion ....................................... 21 2. Barth and the Jewish People: the historical debate ........... 25 The Context of Controversy ....................................... 26 Reading Barth’s Ambiguity ....................................... 30 Barth and the Jewish People: how scholars have understood him32 Barth and the Jews: his personal relationships ........................... 38 Conclusion ....................................... 50 3. Karl Barth -

A Jewish Repair for a Free Church Vision: Reforming Restitutionist Hermeneutics with Peter Ochs

A Jewish Repair for a Free Church Vision: Reforming Restitutionist Hermeneutics With Peter Ochs by Zacharie Klassen A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo and Conrad Grebel University College in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Theological Studies Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2015 © Zacharie Klassen 2015 I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract Over the course of his research on the New Testament and early Christianity, the late Mennonite theologian John Howard Yoder developed a provocative thesis that the historic Jewish-Christian schism was not historically inevitable. Yoder argued that it might have been possible for Jews and Christians to remain together as one people despite a difference of faith regarding the significance of Jesus Christ. While many found Yoder’s thesis refreshing, not all were convinced that it was without its significant theological problems. Peter Ochs, a Jewish pragmatic philosopher, was invited to respond to Yoder’s claims through commentary included in a posthumous publication of essays which contained Yoder’s provocative claims. Ochs argued that Yoder’s thesis perpetuated a form of Christian supersessionism, a Christian teaching that states that the Church has replaced Israel as the people of God. This thesis seeks to expose the roots of Yoder’s supersessionism for the purposes of repairing/reforming Yoder’s vision for the Church and the Church’s relation to the Jews. -

Between the Ritual and the Ethical: Mastery Over the Body in Modern Theories of Ta‘Amei Ha-Mitsvot

Between the Ritual and the Ethical: Mastery Over the Body in Modern Theories of Ta‘amei ha-Mitsvot David Shatz* As Socrates awaits his death,1 his friends urge him to commit suicide. Socrates refuses, because God owns his body; but he then expresses his own general, positive attitude to his impending death. His body is a prison, he declares, incarcerating his soul. The body’s desires and appetites pester him, diverting him from intellectual pursuits; and the body, being a body, cannot attain the highest and only true form of knowledge, knowledge of the abstract world of Forms. Death is therefore liberating and welcome. And not only does the body carry negative value, it is not a person’s true self. Rather, the soul is. If people at the funeral state, “Socrates is being buried,” they are mistaken. It’s not Socrates; it’s a body that Socrates once wore or inhabited.2 Plato’s dualistic view of the human being—that human beings are composites of body and soul—was maintained by most people in the Middle Ages, philosophers and non-philosophers alike. More importantly, the Platonic devaluation of the body (and of matter generally) impacted dramatically on certain medieval Jewish philosophers via Neoplatonism, and these philosophers,3 in contrast to the talmudic sages, were in significant measure champions of asceticism.4 “Duties of the limbs” were means of * Yeshiva University, Department of Philosophy. 1 The reference, of course, is to Plato’s Phaedo. 2 Phaedo 115d–116a. 3 Maimonides’s view is best described as Neoplatonized Aristotelianism. -

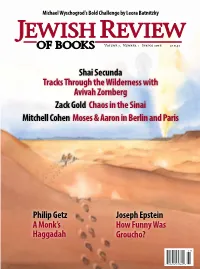

Michael Wyschogrod's Bold Challenge by Leora Batnitzky JEWISH REVIEW of BOOKS Volume 7, Number 1 Spring 2016 $10.45

Michael Wyschogrod's Bold Challenge by Leora Batnitzky JEWISH REVIEW OF BOOKS Volume 7, Number 1 Spring 2016 $10.45 Shai Secunda Tracks Through the Wilderness with Avivah Zornberg Zack Gold Chaos in the Sinai Mitchell Cohen Moses & Aaron in Berlin and Paris Philip Getz Joseph Epstein A Monk’s How Funny Was Haggadah Groucho? Editor Abraham Socher “MIRIAM’S SONG will NEW Senior Contributing Editor RELEASE inspire those who read it, Allan Arkush as it has inspired me.” Art Director W IRIAM S ONG Betsy Klarfeld NE “M ’ S will inspire those who read it, BENJAMIN NETANYAHU Managing Editor SE Amy Newman Smith RELEA as it has inspired me.” BENJAMIN NETANYAHU Editorial Assistant Kate Elinsky Editorial Board 1st Lieutenant Uriel Peretz, Robert Alter Shlomo Avineri Golani Brigade Special Leora Batnitzky Ruth Gavison Forces unit commander, Moshe Halbertal Jon D. Levenson dreamed of becoming the Anita Shapira Michael Walzer first Moroccan chief of staff J. H.H. Weiler Leon Wieseltier of the IDF. Ruth R. Wisse Steven J. Zipperstein On the day he was drafted, Miriam became a woman Publisher waiting for news of disaster. Eric Cohen In November 1998, Uriel Associate Publisher & was fatally wounded by an Director of Marketing explosive device planted Lori Dorr by Hezbollah terrorists. He was 22 years old. JRB Publication Committee Tragically, in March 2010 Miriam was forced to face another test. Her second son, Anonymous Martin J. Gross Major Eliraz Peretz, was killed in an exchange of fire in the 1st Lieutenant Uriel Peretz, Golani Brigade Special Gaza Strip. Forces unit commander, dreamed of becoming the Susan and Roger Hertog first Moroccan chief of staff of the IDF. -

Was the Six Day War a Miracle? What, If Anything, Can Make History Meaningful?

Was the Six Day War a Miracle? What, if anything, can make history meaningful? Rabbi Aryeh Klapper June 26, 2017 YCT Tanakh Yom Iyyun 1 http://www.israelnationalnews.com/News/News.aspx/122435 Miracles in the Six-Day War: Eyewitness Accounts https://unitedwithisrael.org/6-day-war-day-by-day/ Six Day War Miracle: Day by Day http://www.chabad.org/multimedia/timeline_cdo/aid/525341/jewish/Introduction.htm The Miracles of the Six-Day War: A Timeline https://www.ou.org/jewish_action/03/2017/jerusalem-reunited-50-years/ Rabbi Moshe Feinstein Since the generation of King David was a righteous one which believed in God, David could request from God that they be victorious in war through natural means, because even if they were to fight with weapons and all the methods of war and overcome and defeat their enemies, all would recognize that it was God who was responsible for their victory. But in the generation of King Asa, in which the people were not of such great faith, Asa feared that if they would pursue the enemy and overcome it and were then victorious, the people would say that it was due to their own strength, and therefore he requested that God should cause the enemy’s downfall before they even reached them. And Yehoshafat, who was concerned about the diminishment of faith in his generation, feared that even if they were just to pursue the enemy, they would say that they were victorious on their own, and therefore he prayed that God should smite them and he would only recite a song. -

2003-2004Program in Judaic Studies

WINTER 2003-2004Program in Judaic Studies PERELMAN INSTITUTE PRINCETON UNIVERSITY In this Issue 2 Courses NEWSDIRECTOR’S MESSAGE the fantastic. Our motto continues the theme: “Az K’Namér,” which we translate 3 Students Greetings to all of you as we open the “strong as a tiger.” (We justify this reading 3 Class of 2003 new academic year, 2003-2004. since, oddly enough, Hebrew has only 3 Alumni 2003 this one word to refer to all feral cats, 4 Senior Theses 2003 whether panthers, leopards, or tigers!!). NEW PROGRAM NAME: Last 6 Graduate Fellowships spring we noted that our long-awaited And why this quotation? The phrase, “az k’namér,” heads the famous injunction 7 Graduate Students change of name from the Program in from Pirkei Avot (the Sayings of the Jewish Studies (JWS) to the Program in 9 Summer Funding Fathers) bidding the faithful: “Be strong 13 Committee Judaic Studies (JDS) would take effect in (or “bold”) as a tiger, light as an eagle, the summer of 2003. In today’s comput- swift as a deer, and mighty as a lion.” This 13 Support erized world, it took a is the very same sentence that is carved 14 Haverim good deal of sleuthing over the top of the Torah ark doors, just 15 Faculty to ferret out the above the crown. Below you may observe 16 Research and News University’s innumer- the four animals named, including our 22 Events able web sites and docu- “tiger” (who admittedly is depicted here ments in order to make sans stripes). Taken all together—the logo, the motto, and the image—the the shift in nomencla- message is loud and clear: Judaic Studies NEW BUILDING: Update on last ture a reality, but we’ve is strong and thriving at Princeton. -

Shalem College the THING THAT SCARES ME MOST: HEIDEGGER's ANTI-SEMITISM and the RETURN to ZION Od Writes Straight in Crooked L

MICHAEL FAGENBLAT Shalem College THE THING THAT SCARES ME MOST: HEIDEGGER’S ANTI-SEMITISM AND THE RETURN TO ZION But the thing that scared me most was when my enemy came close And I saw that his face looked just like mine. —Bob Dylan, John Brown1 od writes straight in crooked lines, according to an old proverb. Does that mean that without God we are destined for crooked lives? W.H. G Auden thought that wasn’t such a bad thing, for the modern age requires a New Great Commandment: “You shall love your crooked neighbor / With your crooked heart.” But Martin Heidegger, the most important European philosopher of the twentieth century, doubted that one could make good of crookedness. He argued that without God we are abandoned entirely to being and beholden only to being. Our crooked lives aren’t there to be made straight. To try to do so is to betray being, to project anthropological “values” onto being, and in this way to maintain an essentially theological worldview in which humanity plays the role of God. To approach the new epoch we must understand that it is not just God who is dead but also every conception of humanity in the image of God. To subordinate being to moral or political principles, no less than to religious faith, is to betray being and thus deceive ourselves about what we essentially are. For being does not give itself in accordance with reasons, rules or calculations; it does not lay claim in the form of principles, values or categorical imperatives.