Theatre: the Rediscovery of Style and Other Writings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

Text Pages Layout MCBEAN.Indd

Introduction The great photographer Angus McBean has stage performers of this era an enduring power been celebrated over the past fifty years chiefly that carried far beyond the confines of their for his romantic portraiture and playful use of playhouses. surrealism. There is some reason. He iconised Certainly, in a single session with a Yankee Vivien Leigh fully three years before she became Cleopatra in 1945, he transformed the image of Scarlett O’Hara and his most breathtaking image Stratford overnight, conjuring from the Prospero’s was adapted for her first appearance in Gone cell of his small Covent Garden studio the dazzle with the Wind. He lit the touchpaper for Audrey of the West End into the West Midlands. (It is Hepburn’s career when he picked her out of a significant that the then Shakespeare Memorial chorus line and half-buried her in a fake desert Theatre began transferring its productions to advertise sun-lotion. Moreover he so pleased to London shortly afterwards.) In succeeding The Beatles when they came to his studio that seasons, acknowledged since as the Stratford he went on to immortalise them on their first stage’s ‘renaissance’, his black-and-white magic LP cover as four mop-top gods smiling down continued to endow this rebirth with a glamour from a glass Olympus that was actually just a that was crucial in its further rise to not just stairwell in Soho. national but international pre-eminence. However, McBean (the name is pronounced Even as his photographs were created, to rhyme with thane) also revolutionised British McBean’s Shakespeare became ubiquitous. -

The Secret Scripture

Presents THE SECRET SCRIPTURE Directed by JIM SHERIDAN/ In cinemas 7 December 2017 Starring ROONEY MARA, VANESSA REDGRAVE, JACK REYNOR, THEO JAMES and ERIC BANA PUBLICITY REQUESTS: Transmission Films / Amy Burgess / +61 2 8333 9000 / [email protected] IMAGES High res images and poster available to download via the DOWNLOAD MEDIA tab at: http://www.transmissionfilms.com.au/films/the-secret-scripture Distributed in Australia by Transmission Films Ingenious Senior Film Fund Voltage Pictures and Ferndale Films present with the participation of Bord Scannán na hÉireann/ the Irish Film Board A Noel Pearson production A Jim Sheridan film Rooney Mara Vanessa Redgrave Jack Reynor Theo James and Eric Bana THE SECRET SCRIPTURE Six-time Academy Award© nominee and acclaimed writer-director Jim Sheridan returns to Irish themes and settings with The Secret Scripture, a feature film based on Sebastian Barry’s Man Booker Prize-winning novel and featuring a stellar international cast featuring Rooney Mara, Vanessa Redgrave, Jack Reynor, Theo James and Eric Bana. Centering on the reminiscences of Rose McNulty, a woman who has spent over fifty years in state institutions, The Secret Scripture is a deeply moving story of love lost and redeemed, against the backdrop of an emerging Irish state in which female sexuality and independence unsettles the colluding patriarchies of church and nationalist politics. Demonstrating Sheridan’s trademark skill with actors, his profound sense of story, and depth of feeling for Irish social history, The Secret Scripture marks a return to personal themes for the writer-director as well as a reunion with producer Noel Pearson, almost a quarter of a century after their breakout success with My Left Foot. -

FILMS and THEIR STARS 1. CK: OW Citizen Kane: Orson Welles 2

FILMS AND THEIR STARS 1. CK: OW Citizen Kane: Orson Welles 2. TGTBATU: CE The Good, the Bad and the Ugly: Clint Eastwood 3. RFTS: KM Reach for the Sky: Kenneth More 4. FG; TH Forest Gump: Tom Hanks 5. TGE: SM/CB The Great Escape: Steve McQueen and Charles Bronson ( OK. I got it wrong!) 6. TS: PN/RR The Sting: Paul Newman and Robert Redford 7. GWTW: VL Gone with the Wind: Vivien Leigh 8. MOTOE: PU Murder on the Orient Express; Peter Ustinov (but it wasn’t it was Albert Finney! DOTN would be correct) 9. D: TH/HS/KB Dunkirk: Tom Hardy, Harry Styles, Kenneth Branagh 10. HN: GC High Noon: Gary Cooper 11. TS: JN The Shining: Jack Nicholson 12. G: BK Gandhi: Ben Kingsley 13. A: NK/HJ Australia: Nicole Kidman, Hugh Jackman 14. OGP: HF On Golden Pond: Henry Fonda 15. TDD: LM/CB/TS The Dirty Dozen: Lee Marvin, Charles Bronson, Telly Savalas 16. A: MC Alfie: Michael Caine 17. TDH: RDN The Deer Hunter: Robert De Niro 18. GWCTD: ST/SP Guess who’s coming to Dinner: Spencer Tracy, Sidney Poitier 19. TKS: CF The King’s Speech: Colin Firth 20. LOA: POT/OS Lawrence of Arabia: Peter O’Toole, Omar Shariff 21. C: ET/RB Cleopatra: Elizabeth Taylor, Richard Burton 22. MC: JV/DH Midnight Cowboy: Jon Voight, Dustin Hoffman 23. P: AP/JL Psycho: Anthony Perkins, Janet Leigh 24. TG: JW True Grit: John Wayne 25. TEHL: DS The Eagle has landed: Donald Sutherland. 26. SLIH: MM Some like it Hot: Marilyn Monroe 27. -

Thursday Friday

aw — a iic r inice ueorgc ^ in/eii,i v i uvjc.3 — depiemoer X4in, iyy«* The Prince George ★ ★ ★ ★ ...... ......E x c e lle n t M k e > ^ 3 < s ★ ★ ............. ..................Fair ★ ★ ★ ......... ★ ............... Norris. A master of the martial arts AFTERNOON the clutches of a cruel boarding school Harrison, Kay Kendall. The wife of a embarks on a revenge-motivated mistress to search for her soldier titled Englishman must introduce her search for the killers of his adopted 12:00 father. American-raised stepdaughter to son. (22) * *'■> “Spooner” (1989, Comedy- 1:3 0 London society. 8 :3 0 Drama) Robert Urich, Jane QD [12] (:35) “Betrayed by Love" 9 :0 0 (221 (:35) * * x “Eyes in the Night" Kaczmarek. An escaped counterfeiter (1994, Drama) Mare Winningham, © QD [12] **i4 “White Sands" (1942, Mystery) Edward Arnold, Ann finds life quite difficult when he tries to Steven Weber. The sibling of an FBI (1992, Suspense) Willem Dafoe, Harding. When an actor is found mur pass himself off as a high-school informant believes that her sister was Mickey Rourke. A New Mexico sherif dered. a sightless sleuth uncovers an teacher. A (CC) murdered by the married agent with f's unorthodox murder investigation espionage plot in the course of his 5:0 0 whom she had an affair. leads to the center of an international investigation. S3 (:05) * * * s “No Time for arms conspiracy. A (CC) 9 :0 0 Sergeants" (1958, Comedy) Andy 53 (:05) * * “Little Darlings" (1980, [24) (:05) * * s “The Taking of Griffith, Nick Adams. A Georgia farm FRIDAY Comedy) Tatum O’Neal, Kristy Pelham One, Two, Three" (1974, boy inducted into the service sets the McNichol. -

Foxcatcher Directed by Bennett Miller

Sony Pictures Classics Presents An Annapurna Pictures Production Foxcatcher Directed by Bennett Miller Cannes Film Festival 2014 Telluride Film Festival 2014 Toronto International Film Festival 2014 New York Film Festival 2014 Winner - Best Director, Cannes Film Festival 2014 134 mins | Rated R | Opens 11/14/14 (NY/LA) East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor 42West Block Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Scott Feinstein Max Buschman Carmelo Pirrone 220 West 42nd Street Blair Bender Maya Anand 12th floor 6100 Wilshire Blvd., 550 Madison Ave New York, NY 10036 Ste. 170 New York, NY 10022 212-277-7555 Los Angeles, CA 90048 212-833-8833 tel 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8844 fax 323-634-7030 fax FOXCATCHER The Cast John du Pont STEVE CARELL Mark Schultz CHANNING TATUM Dave Schultz MARK RUFFALO Jean du Pont VANESSA REDGRAVE Nancy Schultz SIENNA MILLER Jack ANTHONY MICHAEL HALL Henry Beck GUY BOYD Documentary Filmmaker DAVE “DOC” BENNETT The Filmmakers Director BENNETT MILLER Written by E. MAX FRYE DAN FUTTERMAN Producers MEGAN ELLISON BENNETT MILLER JON KILIK ANTHONY BREGMAN Executive Producers CHELSEA BARNARD RON SCHMIDT MARK BAKSHI MICHAEL COLEMAN TOM HELLER JOHN P. GUIRA Co-Producer SCOTT ROBERTSON Director of Photography GREIG FRASER Production Designer JESS GONCHOR Editor STUART LEVY CONOR O’NEILL JAY CASSIDY Costume Designer KASIA MAIMONE WALICKA Music ROB SIMONSEN Additional Music WEST DYLAN THORDSON Valley Forge Theme MYCHAEL DANNA Casting Director JEANNE McCARTHY Makeup Designer BILL CORSO Hair Department Head KATHRINE GORDON Wrestling Coordinator JOHN GUIRA Wrestling Choreographer JESSE JANTZEN 2 FOXCATCHER Synopsis Based on true events, FOXCATCHER tells the dark and fascinating story of the unlikely and ultimately tragic relationship between an eccentric multi-millionaire and two champion wrestlers. -

Shakespeare, William Shakespeare

Shakespeare, William Shakespeare. Julius Caesar The Shakespeare Ralph Richardson, Anthony SRS Caedmon 3 VG/ Text Recording Society; Quayle, John Mills, Alan Bates, 230 Discs VG+ Howard Sackler, dir. Michael Gwynn Anthony And The Shakespeare Anthony Quayle, Pamela Brown, SRS Caedmon 3 VG+ Text Cleopatra Recording Society; Paul Daneman, Jack Gwillim 235 Discs Howard Sackler, dir. Great Scenes The Shakespeare Anthony Quayle, Pamela Brown, TC- Caedmon 1 VG/ Text from Recording Society; Paul Daneman, Jack Gwillim 1183 Disc VG+ Anthony And Howard Sackler, dir. Cleopatra Titus The Shakespeare Anthony Quayle, Maxine SRS Caedmon 3 VG+ Text Andronicus Recording Society; Audley, Michael Horden, Colin 227 Discs Howard Sackler, dir. Blakely, Charles Gray Pericles The Shakespeare Paul Scofield, Felix Aylmer, Judi SRS Caedmon 3 VG+ Text Recording Society; Dench, Miriam Karlin, Charles 237 Discs Howard Sackler, dir. Gray Cymbeline The Shakespeare Claire Bloom, Boris Karloff, SRS- Caedmon 3 VG+ Text Recording Society; Pamela Brown, John Fraser, M- Discs Howard Sackler, dir. Alan Dobie 236 The Comedy The Shakespeare Alec McCowen, Anna Massey, SRS Caedmon 2 VG+ Text Of Errors Recording Society; Harry H. Corbett, Finlay Currie 205- Discs Howard Sackler, dir. S Venus And The Shakespeare Claire Bloom, Max Adrian SRS Caedmon 2 VG+ Text Adonis and A Recording Society; 240 Discs Lover's Howard Sackler, dir. Complaint Troylus And The Shakespeare Diane Cilento, Jeremy Brett, SRS Caedmon 3 VG+ Text Cressida Recording Society; Cyril Cusack, Max Adrian 234 Discs Howard Sackler, dir. King Richard The Shakespeare John Gielgud, Keith Michell and SRS Caedmon 3 VG+ Text II Recording Society; Leo McKern 216 Discs Peter Wood, dir. -

'Just One More

‘JUST ONE MORE GENERATION’ JOELY RICHARDSON ‘JUST ONE MORE GENERATION’ Joely Richardson is following both her mother and her sister by appearing in an Ibsen play about love and death. She talks movingly about the loss of Natasha, the sister she adored, and the future of her family dynasty. By Caroline Scott. Photograph: Harry Borden JOELY RICHARDSON oely Richardson didn’t really want to She is palpably, disconcertingly nervous. was my touchstone until she wasn’t there. All talk to me. “Can’t you send a man?” she Her hands flutter up to her face like birds the dreams you have, the common language, had asked through her agent, hoping a coming down to rest in her lap before flying the shared history…Everything was levelled male interviewer might focus more on up again. “I was saying to Mum this morning, when she left us. Then, just as we were getting the work and less on the sadness of the it’s probably completely insane of me to over the shock, Corin died, then Lynnie. We past two-and-a-half years. First, Joely’s have taken this on, but it’s too late now. She were just reeling.” older sister, Natasha, died after a skiing reminded me I felt like this before I began At the same time, Daisy, her daughter with accident in 2009. Then, last year, Corin rehearsing Side Effects [she played a bipolar her ex-husband, the producer Tim Bevan, Jand Lynn Redgrave, brother and sister politician’s wife in Michael Weller’s portrait left home to study in New York. -

Atonement (2007) Compiled by Jay Seller

Literature to Film, lecture on Atonement (2007) Compiled by Jay Seller Atonement (2007) Universal Pictures Director: Joe Wright Screenwriter: Christopher Hampton Novel: Ian McEwan 123 minutes Cast Cecilia Tallis Keira Knightley Robbie Turner James McAvoy Briony Tallis,Briony Romola Garai Older Briony Vanessa Redgrave Briony Taliis,Briony Saoirse Ronan Grace Turner Brenda Blethyn Singing Housemaid Allie MacKay Betty Julia Ann West Lola Quincey Juno Temple Jackson Quincey Charlie Von Simpson Leon Tallis Patrick Kennedy Paul Marshall Benedict Cumberbatch Emily Tallis Harriet Walter Fiona MacGuire Michelle Duncan Sister Drummond Gina McKee Police Constable Leander Deeny Luc Cornet Jeremie Renier Police Sergeant Peter McNeil O’Connor Tommy Nettle Daniel Mays Danny Hardman Alfie Allen Pierrot,Pierrot Jack Harcourt Frenchmen Michel Vuillemoz Jackson,Jackson Ben Harcourt Frenchmen Lionel Abelanski Frank Mace Nonso Anozie Naval Officer Tobias Menzies Crying Soldier Paul Stocker Police Inspector Peter Wright Solitary Sunbather Alex Noodle Vicar John Normington Mrs. Jarvis Wendy Nottingham Beach Soldier Roger Evans, Bronson Webb, Ian Bonar, Oliver Gilbert Interviewer Anthony Minghella Soldier in Bray Bar Jamie Beamish, Johnny Harris, Nick Bagnall, Billy Seymour, Neil Maskell Soldier With Ukulele Paul Harper Probationary Nurse Charlie Banks, Madeleine Crowe, Olivia Grant, Scarlett Dalton, Katy Lawrence, Jade Moulla, Georgia Oakley, Alice Orr-Ewing, Catherine Philps, Bryony Reiss, DSarah Shaul, Anna Singleton, Emily Thomson Hospital Admin Assistant Kelly Scott Soldier at Hospital Entrance Mark Holgate Registrar Ryan Kiggell Staff Nurse Vivienne Gibbs Second Soldier at Hospital Entrance Matthew Forest Injured Sergeant Richard Stacey Soldier Who Looks Like Robbie Jay Quinn Mother of Evacuees Tilly Vosburgh Evacuee Child Angel Witney, Bonnie Witney, Webb Bem 1 Primary source director’s commentary by Joe Wright. -

Theatre Archive Project Archive

University of Sheffield Library. Special Collections and Archives Ref: MS 349 Title: Theatre Archive Project: Archive Scope: A collection of interviews on CD-ROM with those visiting or working in the theatre between 1945 and 1968, created by the Theatre Archive Project (British Library and De Montfort University); also copies of some correspondence Dates: 1958-2008 Level: Fonds Extent: 3 boxes Name of creator: Theatre Archive Project Administrative / biographical history: Beginning in 2003, the Theatre Archive Project is a major reinvestigation of British theatre history between 1945 and 1968, from the perspectives of both the members of the audience and those working in the theatre at the time. It encompasses both the post-war theatre archives held by the British Library, and also their post-1968 scripts collection. In addition, many oral history interviews have been carried out with visitors and theatre practitioners. The Project began at the University of Sheffield and later transferred to De Montfort University. The archive at Sheffield contains 170 CD-ROMs of interviews with theatre workers and audience members, including Glenda Jackson, Brian Rix, Susan Engel and Michael Frayn. There is also a collection of copies of correspondence between Gyorgy Lengyel and Michel and Suria Saint Denis, and between Gyorgy Lengyel and Sir John Gielgud, dating from 1958 to 1999. Related collections: De Montfort University Library Source: Deposited by Theatre Archive Project staff, 2005-2009 System of arrangement: As received Subjects: Theatre Conditions of access: Available to all researchers, by appointment Restrictions: None Copyright: According to document Finding aids: Listed MS 349 THEATRE ARCHIVE PROJECT: ARCHIVE 349/1 Interviews on CD-ROM (Alphabetical listing) Interviewee Abstract Interviewer Date of Interview Disc no. -

The Routledge Companion to Directors' Shakespeare Glen Byam

This article was downloaded by: 10.3.98.104 On: 26 Sep 2021 Access details: subscription number Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London SW1P 1WG, UK The Routledge Companion to Directors’ Shakespeare John Russell Brown Glen Byam Shaw Publication details https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203932520.ch3 Nick Walton Published online on: 26 Apr 2010 How to cite :- Nick Walton. 26 Apr 2010, Glen Byam Shaw from: The Routledge Companion to Directors’ Shakespeare Routledge Accessed on: 26 Sep 2021 https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203932520.ch3 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR DOCUMENT Full terms and conditions of use: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/legal-notices/terms This Document PDF may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproductions, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The publisher shall not be liable for an loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. 3 GLEN BYAM SHAW Nick Walton Glen Byam Shaw’s direction was commonly perceived as being ‘assured and unobtrusive’, ‘blessedly straightforward’, ‘a model of sensitive presentation’, and above all ‘sympathetic to the players and the play’. His direction was also said to possess a ‘Mozartian quality’, ‘a radiance’ and an ‘unobtrusive charm’. -

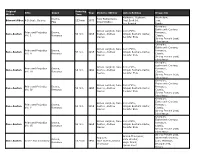

Original Writer Title Genre Running Time Year Director/Writer Actor

Original Running Title Genre Year Director/Writer Actor/Actress Keywords Writer Time Katharine Hepburn, Alcoholism, Drama, Tony Richardson; Edward Albee A Delicate Balance 133 min 1973 Paul Scofield, Loss, Play Edward Albee Lee Remick Family Georgian, Eighteenth Century, Simon Langton; Jane Colin Firth, Pride and Prejudice Drama, Romance, Jane Austen 53 min 1995 Austen, Andrew Crispin Bonham-Carter, Vol. I Romance Classic, Davies Jennifer Ehle Strong Female Lead, Inheritance Georgian, Eighteenth Century, Simon Langton; Jane Colin Firth, Pride and Prejudice Drama, Romance, Jane Austen 54 min 1995 Austen, Andrew Crispin Bonham-Carter, Vol. II Romance Classic, Davies Jennifer Ehle Strong Female Lead, Inheritance Georgian, Eighteenth Century, Simon Langton; Jane Colin Firth, Pride and Prejudice Drama, Romance, Jane Austen 53 min 1995 Austen, Andrew Crispin Bonham-Carter, Vol. III Romance Classic, Davies Jennifer Ehle Strong Female Lead, Inheritance Georgian, Eighteenth Century, Simon Langton; Jane Colin Firth, Pride and Prejudice Drama, Romance, Jane Austen 53 min 1995 Austen, Andrew Crispin Bonham-Carter, Vol. IV Romance Classic, Davies Jennifer Ehle Strong Female Lead, Inheritance Georgian, Eighteenth Century, Simon Langton; Jane Colin Firth, Pride and Prejudice Drama, Romance, Jane Austen 50 min 1995 Austen, Andrew Crispin Bonham-Carter, Vol. V Romance Classic, Davies Jennifer Ehle Strong Female Lead, Inheritance Georgian, Eighteenth Century, Simon Langton; Jane Colin Firth, Pride and Prejudice Drama, Romance, Jane Austen 52 min 1995 Austen,