Participants' Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 43: Summer 2010/11

Journal of the Melbourne CriCket Club library issue 43, suMMer 2010/2011 Cro∫se: f. A Cro∫ier, or Bi∫hops ∫taffe; also, a croo~ed ∫taffe wherewith boyes play at cricket. This Issue: Celebrating the 400th anniversary of our oldest item, Ashes to Ashes, Some notes on the Long Room, and Mollydookers in Australian Test Cricket Library News “How do you celebrate a Quadricentennial?” With an exhibition celebrating four centuries of cricket in print The new MCC Library visits MCC Library A range of articles in this edition of The Yorker complement • The famous Ashes obituaries published in Cricket, a weekly cataloguing From December 6, 2010 to February 4, 2010, staff in the MCC the new exhibition commemorating the 400th anniversary of record of the game , and Sporting Times in 1882 and the team has swung Library will be hosting a colleague from our reciprocal club the publication of the oldest book in the MCC Library, Randle verse pasted on to the Darnley Ashes Urn printed in into action. in London, Neil Robinson, research officer at the Marylebone Cotgrave’s Dictionarie of the French and English tongues, published Melbourne Punch in 1883. in London in 1611, the same year as the King James Bible and the This year Cricket Club’s Arts and Library Department. This visit will • The large paper edition of W.G. Grace’s book that he premiere of Shakespeare’s last solo play, The Tempest. has seen a be an important opportunity for both Neil’s professional presented to the Melbourne Cricket Club during his tour in commitment development, as he observes the weekday and event day The Dictionarie is a scarce book, but not especially rare. -

The Great War, 1914-18 Biographies of the Fallen

IRISH CRICKET AND THE GREAT WAR, 1914-18 BIOGRAPHIES OF THE FALLEN BY PAT BRACKEN IN ASSOCIATION WITH 7 NOVEMBER 2018 Irish Cricket and the Great War 1914-1918 Biographies of The Fallen The Great War had a great impact on the cricket community of Ireland. From the early days of the war until almost a year to the day after Armistice Day, there were fatalities, all of whom had some cricket heritage, either in their youth or just prior to the outbreak of the war. Based on a review of the contemporary press, Great War histories, war memorials, cricket books, journals and websites there were 289 men who died during or shortly after the war or as a result of injuries received, and one, Frank Browning who died during the 1916 Easter Rising, though he was heavily involved in organising the Sporting Pals in Dublin. These men came from all walks of life, from communities all over Ireland, England, Scotland, Wales, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, South Africa, India and Sri Lanka. For all but four of the fifty-two months which the war lasted, from August 1914 to November 1918, one or more men died who had a cricket connection in Ireland or abroad. The worst day in terms of losses from a cricketing perspective was the first day of the Battle of the Somme, 1 July 1916, when eighteen men lost their lives. It is no coincidence to find that the next day which suffered the most losses, 9 September 1916, at the start of the Battle of Ginchy when six men died. -

Charities Will Open Nursery Home Next Week

Member of Audit Bureau of CireulaHons CHARITIES WILL OPEN NURSERY HOME NEXT WEEK Contents Copyrighted by the Catholic Press Society, Ine- 1948— Permission to reproduce. Except on Pupils to Be Excused Articles Otherwise Marked, given After 12 M. Friday Following Issue St. Clara’s Original DENVER CATHOLIC Orphanage Building For Annual Retreat To House Institntion Winner in Art CoBMSsioR lo CaUnlie Stadealt io Public Denver Deaneiy Is Sponsoring Unit; Unproeo- High Sehoolc Is Gourtssy Greatly Appre R Ea S T ER deolod Nninber of Infaits Under Calholie ciated by Arcbdiecesaa Educators The National Catholic Welfare Conference News Service Supplies The Denver Catholic Register. We Have Also the International News Service (Wire and Mail), a Large Special Service, Seven Smaller Gore Greales Soriois GondHion For the first time since the beginning of the annual re Services, Photo Features, and Wide World Photos. (3 cents per copy) treats for Catholic pupi|s of Denver public high schools, the A nursery home that will accommodate approximately students will this year be excused from classes to attend the VOI* XU. No. 27. DENVER, COLO., THURSDAY, FEB. 28, 1946. $1 PER YEAR 40 infants will be opened the first week of March in the exercises. In former years the retreat was always held at original St. Clara’s orphanage building in Denver, the Rt. the time of the spring vacation in the public schools, but this Rev. Monsignor John R. Mulroy, director of Catholic Char year Charles E. Greene, superintendent of Denver public ities, announced Wednesday. The institution, to be known schools, was petitioned to release the Catholic pupils during as the Denver Deanery Nursery home, will be established as two regular class days. -

DECIDES on ITEMS/ Improvements

FATHERREYNOLDSHERO OPEN GATES OFTHESEA, FLASHLIGHT Oif the wreckat we!STPORT/CONN. [ CFF LEGATION BESIEGED < DECIDES ON ITEMS/ IULGARIAHOLDS (Continued from First Pane ) Asks 4or OF FATAL RAILCRASH HAVEIPSOFWORLD - BYGREEKCITIZENS. Charity Board lanla and Montenegro combined, and ought the Turkish soldiers would nave on ss difflculty with tlie troops of the ImprovementsBuildings. He of Balkan kingdoms. Whatever the lite Reservists and Mgr. Shahan Denies It Was Keynote Pageant Play of the fighting, however, the greatisic Others Presented iwers declared that the b»ve status <juo Who Aided Rescue at at His Majesty's tall he maintained in the peninsula, and of Prospect of WarInquire PROVISIONS IN ESTIMATES le Turkish government has absolute » tith, he said, that the powers will keep Westport. Theater, London. ieir promises. in the Balkans. i Sums for Work on Proposed City SMASH CONSUL S WINDOWS. Reports that Mgr. Thomas Shahan. Spuria! Oabletrrnm to The Star. At the Greek legation in this city It and for , Hospital Tugboat of the Catholic University, was rectorthe LONDON, October 5.."We have opened emonstration by Turkish Citizens was stated today that nearly 100 Are Included. ' priest mentioned in news dispatches the prates of the sea. We have given you and telegrams have been Inquiries i as haying ministered to the needsyesterdaythe keys of the world. Against Oreece in Constantinople. fi-om Greeks In Washington an«lreceived (pf the dying at the scene of the wreck "The little spot you stand on has CONSTANTINOPLE, October 5..A throughout -

Lite Wooster Voice - VOL

The College of Wooster Open Works The oV ice: 2001-2011 "The oV ice" Student Newspaper Collection 2-4-2011 The oW oster Voice (Wooster, OH), 2011-02-04 Wooster Voice Editors Follow this and additional works at: https://openworks.wooster.edu/voice2001-2011 Recommended Citation Editors, Wooster Voice, "The oosW ter Voice (Wooster, OH), 2011-02-04" (2011). The Voice: 2001-2011. 532. https://openworks.wooster.edu/voice2001-2011/532 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the "The oV ice" Student Newspaper Collection at Open Works, a service of The oC llege of Wooster Libraries. It has been accepted for inclusion in The oV ice: 2001-2011 by an authorized administrator of Open Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. lite Wooster Voice - VOL. CXXX, ISSUE XIII- A STUDENT PUBLICATION SINCE 1 883 FRIDAY, February 4, 201 1 'You can jail a Revolutionary, but you can't jail the Revolution." Huey Newton Senior receives top cricket award Dite-Giz- ed Mews Grainne Carlin CAMPUS GSE proaram receives major honor Staff Writer The College of Wooster's Global Social Entrepreneurship (Glob- It started on Homecoming week- al SE) program has been cited for excellence by the Institute of In- end, when over 900 fans helped The ternational Excellence (HE). The Global SE program will receive College of Wooster break a record the Andrew Heiskell Award for innovation in international educa- for the largest crowd to ever attend tion at the Sixth Annual Best Practices in Internationalization Con- a United States collegiate cricket ference on March 18. -

View a PDF Version

see things in a new light The splendor of Westinghouse Lighting fixtures, ceiling fans and light bulbs reveals the eye-catching style and beauty of your home. To learn more, call 800-999-2226 or visit www.westinghouselighting.com. , WESTINGHOUSE, and INNOVATION YOU CAN BE SURE OF are trademarks of Westinghouse Electric Corporation. Used under license by Westinghouse Lighting. All Rights Reserved. 2019 WESTINGHOUSE LIGHTING 984_ALADirectoryAD_2019.inddALA AD Pages_2020.indd 1 1 10/16/194/7/20 1:04 1:14 PM PM “I set the lights to come on at dusk so my family always comes back to a welcoming home... especially when I am out of town.” — Philadelphia, PA Upgrade your life. Start with peace of mind. Discover how to personalize your home with Caséta lighting controls: dimmers, remotes, mobile app, or your own voice activated device. Simple to use and easy to set up. Visit CasetaWireless.com. Seamlessly integrates with: by ©2019 Lutron Electronics Co., Inc. Lutron is a trademark of Lutron Electronics Co., Inc., registered in the U.S. and other countries. For a complete list of all Lutron registered and common law trademarks, please visit lutron.com/trademarks. HomeKit is a trademark of Apple Inc. ALA AD Pages_2020.indd 2 4/7/20 1:04 PM Table of Contents 2020 ACTION AGENDA INDEX Advertising Marketing & Communications .............d-e Education ...................................................................f 2020 Annual Conference ...........................................g Training & Certification ..............................................h-i -

The SABR UK Number 10

1 The SABR UK Number 10 Examiner July 1998 THE JOURNAL OF THE BOBBY THOMSON CHAPTER OF THE SOCIETY FOR AMERICAN BASEBALL RESEARCH (UK) 1998 SABR UK AGM by Martin Hoerchner from Honourary President Norman Minnesota Twins. Clark is an Macht, and then a message from attorney and the Major League The Seventh Annual So- the big enchilada, SABR Presi- representative for the owners in ciety for American Baseball dent Larry Gerlach, who expressed labour negotiations, and was a his regret at being unable attend negotiator in the strikes of 1980 Research UK Annual Gen- and his appreciation for SABR and ‘81. eral Meeting took place at its UK’s accomplishments. Mike then That was the subject of his spiritual home, the Kings main presentation, the history of Clerkenwell Public of labour negotiations in base- House, on Saturday April ball, which he presented with insight and humour. Clark noted 25. That’s a mouthful, so that the constant conflict of play- I’ll just say that the ‘98 ers vs. owners is as old as the SABR UK AGM was held at game itself, or at least the pro- the “Kings”. fessional game, which game into I think it was our best meet- play in 1869. He noted the im- ing yet, not only in the numbers plementation of the reserve rule attending, but in the quality of in 1879 as a major point of con- the presentations given. flict with the players, but one Hugh Robinson opened the that the owners felt was neces- meeting, explaining that we were sary to avoid plunging the game going to do things backwards. -

This Entire Document

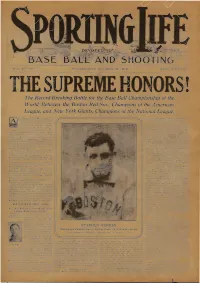

VOL. 6O—NO. 7 PHILADELPHIA, OCTOBER T9, 1912 PRICE 5 CENTS THE SUPREME HONORS! The Record-Breaking Battle for the Base Ball Championship of the World, Between the Boston Red Sox, Champions of the American League, and New York Giants, Champions of the National League. S "Sporting Life" goes to press the stages when defeat seemed certain with the 1912 World©s Series is drawing to good pitching Tesreau was serving up to a conclusion and will be a matter HIS SUDDSN COLLAPSE of history ere this greets the read in the seventh inning. Doyle was the star of er. At this writing, Tuesday, the day for New York in fielding and batting. October 15, the seventh game of Myers also rose to an emergency in the last the series is being played in Bos inning, and Murray, the failure of 1911, made ton and in the event of Boston©s success the his first hit in a World©s Series, and with it series will be ended with the Boston Ameri scored both New York runs in.the third in can League team as the winner of the great ning. Fletcher had a bad day, striking out series by four games to two games for the three times, when a hit on two occasions would New York Nationals, the second game of the have obviated his team©s defeat. The bulk series being an 11-inning draw. Should New of Boston©s field work was done by catcher York win on this day the rival teams will be Cady, who made a splendid World©s Series tied with three victories and defeats each, debut, and by Wagner with brilliant short field and the deciding game will be played on Wed work and timely batting; but the real hero of nesday, Octob-er 16. -

The Cambridge Companion to Cricket Edited by Anthony Bateman , Jeffrey Hill Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-16787-1 — The Cambridge Companion to Cricket Edited by Anthony Bateman , Jeffrey Hill Frontmatter More Information the cambridge companion to cricket Few other team sports can equal the global reach of cricket. Rich in history and tradition, it is both quintessentially English and expansively international, a game that has evolved and changed dramatically in recent times. Cricket has a unique adaptability and a continuing ability to excite national passions. Demonstrating how the history of cricket and its international popularity is entwined with British imperial expansion, this book examines the social and political impact of the game in a variety of cultural sites: the West Indies, India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand. An international team of contributors explores the enduring infl uence of cricket on English identity, examines why cricket has seized the imagination of so many literary fi gures and provides profi les of iconic players including Don Bradman, Brian Lara and Sachin Tendulkar. Presenting a global panoramic view of cricket’s complicated development and its political and sporting controversies, the book provides a rich insight into a unique sporting and cultural heritage. anthony bateman is a freelance writer and editor and an Honorary Visiting Research Fellow at the International Centre for Sports History and Culture at De Montfort University, Leicester, UK. jeffrey hill is Emeritus Professor of Historical and Cultural Studies at De Montfort University, -

Anna Held Mtterwatloaal Aad •Ratted for Tn Tmjm Ikwmf Raa Matehe* He Howled Oo an ? Ran for in Eighth

DETROIT TIMES MONDAY, MAY 22, 1914. IjWning Question of the Day—Can Dauss Come Back as Red Sox the Tiger camp. It Is known that Jinx? Manager Jennings Is contemplating SHEtC -V\ *-*¦- -»•*§) of some shifts, one of which fill take Ml |[l Stars Ann Arbor Meet BOSTON NEXT J^l GIANTS ARE THE Heilman out of the ou'.tield Harry bciongi* at first base and probably STANDINGS at go - Should Twinkle Classic ON TjOE SKED w ill there. Harper may play l NOW batting prowess SENSATION 1 1-tht field until be- league. and although Meredith, Overton and comes more important than fielding American Murray Bed Sox Not As Formidable ssill, probably will, McGraw’s Speeding (Man Only Smith and Are several others can better Ids lime when Crawford Are Beating replace him. •TANDHU Games Behind Expected to in of* 1:55 1-.'*. he should be good for a As In 1915; Three Shine Dalton, the former Fed star, will W I.Pet. W UPet fourth place at least. The Michigan Few Teams Cleland ?l 11 4r,fi Detroit 1* IT .4M in »•*• League KIgUNaM «>*? Httlhty Jennings figuring on some more shifts Leaders Intercollegiate on to not be retained. Jack has not shown Wsh’ton 30 II 444 ChlruKo 1.1 111 .41* is fans are counting him make N IS 1 s 17.414 do It. If Hughey If* not »»twW any defensive ability, and this bat- York 14 .5 At lclUs 13 PP^SBSfJRNow ftatfca time to in rTju.s even better time, and he will doubt- flostou. -

Find Book # Bart King

DV8KXEL0M5MS \ Doc // Bart King Bart King Filesize: 5.72 MB Reviews The best publication i actually study. I actually have study and so i am confident that i am going to likely to study once more yet again later on. You will not sense monotony at at any moment of your respective time (that's what catalogs are for relating to if you ask me). (Ernest Bergnaum) DISCLAIMER | DMCA JPOPPHS3QMKF \ Book # Bart King BART KING Alphascript Publishing. Taschenbuch. Condition: Neu. Neuware - John Barton 'Bart' King (October 19, 1873 October 17, 1965) was an American cricketer, active in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. King was one of the Philadelphian cricketers that played from the end of the 19th century until the outbreak of World War I. This period of cricket in the United States was dominated by gentleman players men of independent wealth who did not need to work. King was an amateur from a middle-class family, who was able to devote time to cricket thanks to a job set up by his teammates. King was a skilled batsman, but proved his worth as a bowler. During his career, he set numerous records in North America and led the first-class bowling averages in England in 1908. He successfully competed against the best cricketers from England and Australia. King was the dominant bowler on his team when it toured England in 1897, 1903, and 1908. He dismissed batsmen with his unique delivery, which he called the 'angler,' and helped develop the art of swing bowling in the sport. -

SBAC Math CAT - 5Th Grade

Student Name: ______________________________ 5th Grade English Language Arts A Cure for Carlotta By Bart King A boy stood on deck and sniffed the salty sea air as the ship pitched back and forth. The smell of the sea was familiar and comforting. The boy’s earliest memories were of being at sea with his father. They would fish for hours, just the two of them, surrounded by the blue waters of the Mediterranean Sea. Now Enzio and his family were on a giant ship crossing the Atlantic. Also on board were hundreds of other people, mostly Italians like Enzio’s family. There were more people on board than lived in his entire village back home in Trevilla. Enzio clattered down the iron steps to the steerage deck and dove into his bunk. He rested his head against his pillow. Trevilla wasn’t his home anymore. Gone was the fishing boat. Gone was the Mediterranean blue that he’d always taken for granted. Who knew what kind of home America would be? One of the passengers was a girl named Carlotta. Her family was from Rome. Carlotta had been quick to tell him this on the first day of the voyage. “New York will not be so different from Rome,” Carlotta had said. “They are both great cities, but of course Rome is better. My father has already been to America twice. He is going to open a big department store downtown. My father had a successful business in Rome; all the wealthy ladies would buy from him.” Carlotta loved to talk about herself, her family, and the rich and powerful people they knew.