About Ewing Tumors What Is the Ewing Family of Tumors?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Combination of Cabazitaxel and Plicamycin Induces Cell Death in Drug Resistant B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

Clinical and Translational Science Institute Centers 9-1-2018 Combination of cabazitaxel and plicamycin induces cell death in drug resistant B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia Rajesh R. Nair West Virginia University Debbie Piktel West Virginia University Werner J. Geldenhuys West Virginia University Laura F. Gibson West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/ctsi Part of the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons Digital Commons Citation Nair, Rajesh R.; Piktel, Debbie; Geldenhuys, Werner J.; and Gibson, Laura F., "Combination of cabazitaxel and plicamycin induces cell death in drug resistant B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia" (2018). Clinical and Translational Science Institute. 34. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/ctsi/34 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Centers at The Research Repository @ WVU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Clinical and Translational Science Institute by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author ManuscriptAuthor Manuscript Author Leuk Res Manuscript Author . Author manuscript; Manuscript Author available in PMC 2019 September 01. Published in final edited form as: Leuk Res. 2018 September ; 72: 59–66. doi:10.1016/j.leukres.2018.08.002. Combination of cabazitaxel and plicamycin induces cell death in drug resistant B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia Rajesh R. Naira, Debbie Piktelb, Werner J. Geldenhuysc, -

Pediatric Soft Tissue Tumors of Head and Neck – an Update and Review

IP Archives of Cytology and Histopathology Research 2020;5(4):266–273 Content available at: https://www.ipinnovative.com/open-access-journals IP Archives of Cytology and Histopathology Research Journal homepage: https://www.ipinnovative.com/journals/ACHR Review Article Pediatric soft tissue tumors of head and neck – An update and review Shruti Nayak1, Amith Adyanthaya2, Soniya Adyanthaya1,*, Amarnath Shenoy3, M Venkatesan1 1Dept. of Oral Pathology and Microbiology, Yenepoya Dental College, Yenepoya University, Mangalore, Karnataka, India 2Dept. of Pedodontics, KMCT Dental College, Kozhikode, Kerala, India 3Dept. of Conservative and Endodontics, Century Dental College Poinachi, Kasargod, Kerala, India ARTICLEINFO ABSTRACT Article history: Pediatric malignancies especially sarcomas are the most common and predominant cause of mortality in Received 01-12-2020 children. Such ongoing efforts are crucial to better understand the etiology of childhood cancers, get better Accepted 17-12-2020 the survival rate for malignancies with a poor prognosis, and maximize the quality of life for survivors. Available online 30-12-2020 In this review article we authors aim to discuss relatively common benign and malignant connective tissue tumors (soft tissue tumor), focusing on current management strategies and new developments, as they relate to the role of the otolaryngologist– head and neck surgeon. Other rarer paediatric head and neck tumors Keywords: beyond the scope of this review Pediatric Sarcoma © This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Soft tissue License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and Tumor reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. -

Infiltrating Myeloid Cells Drive Osteosarcoma Progression Via GRM4 Regulation of IL23

Published OnlineFirst September 16, 2019; DOI: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-0154 RESEARCH BRIEF Infi ltrating Myeloid Cells Drive Osteosarcoma Progression via GRM4 Regulation of IL23 Maya Kansara 1 , 2 , Kristian Thomson 1 , Puiyi Pang 1 , Aurelie Dutour 3 , Lisa Mirabello 4 , Francine Acher5 , Jean-Philippe Pin 6 , Elizabeth G. Demicco 7 , Juming Yan 8 , Michele W.L. Teng 8 , Mark J. Smyth 9 , and David M. Thomas 1 , 2 ABSTRACT The glutamate metabotropic receptor 4 (GRM4 ) locus is linked to susceptibility to human osteosarcoma, through unknown mechanisms. We show that Grm4 − / − gene– targeted mice demonstrate accelerated radiation-induced tumor development to an extent comparable with Rb1 +/ − mice. GRM4 is expressed in myeloid cells, selectively regulating expression of IL23 and the related cytokine IL12. Osteosarcoma-conditioned media induce myeloid cell Il23 expression in a GRM4-dependent fashion, while suppressing the related cytokine Il12 . Both human and mouse osteosarcomas express an increased IL23:IL12 ratio, whereas higher IL23 expression is associated with worse survival in humans. Con- sistent with an oncogenic role, Il23−/− mice are strikingly resistant to osteosarcoma development. Agonists of GRM4 or a neutralizing antibody to IL23 suppressed osteosarcoma growth in mice. These fi ndings identify a novel, druggable myeloid suppressor pathway linking GRM4 to the proinfl ammatory IL23/IL12 axis. SIGNIFICANCE: Few novel systemic therapies targeting osteosarcoma have emerged in the last four decades. Using insights gained from a genome-wide association study and mouse modeling, we show that GRM4 plays a role in driving osteosarcoma via a non–cell-autonomous mechanism regulating IL23, opening new avenues for therapeutic intervention. -

PEMD-91-12BR Off-Label Drugs: Initial Results of a National Survey

11 1; -- __...._-----. ^.-- ______ -..._._ _.__ - _........ - t Ji Jo United States General Accounting Office Washington, D.C. 20648 Program Evaluation and Methodology Division B-242851 February 25,199l The Honorable Edward M. Kennedy Chairman, Committee on Labor and Human Resources United States Senate Dear Mr. Chairman: In September 1989, you asked us to conduct a study on reimbursement denials by health insurers for off-label drug use. As you know, the Food and Drug Administration designates the specific clinical indications for which a drug has been proven effective on a label insert for each approved drug, “Off-label” drug use occurs when physicians prescribe a drug for clinical indications other than those listed on the label. In response to your request, we surveyed a nationally representative sample of oncologists to determine: . the prevalence of off-label use of anticancer drugs by oncologists and how use varies by clinical, demographic, and geographic factors; l the extent to which third-party payers (for example, Medicare intermediaries, private health insurers) are denying payment for such use; and l whether the policies of third-party payers are influencing the treatment of cancer patients. We randomly selected 1,470 members of the American Society of Clinical Oncologists and sent them our survey in March 1990. The sam- pling was structured to ensure that our results would be generalizable both to the nation and to the 11 states with the largest number of oncologists. Our response rate was 56 percent, and a comparison of respondents to nonrespondents shows no noteworthy differences between the two groups. -

Consumer Medicine Information

DBL™ Docetaxel Concentrated Injection docetaxel Consumer Medicine Information What is in this leaflet It works by stopping cells from • wheezing or difficulty breathing growing and multiplying. or a tight feeling in your chest This leaflet answers some common Ask your doctor if you have any • swelling of the face, lips, tongue questions about DBL Docetaxel, questions about why this medicine or other parts of the body Concentrated Injection. has been prescribed for you. • rash, itching, hives or flushed, red It does not contain all the available Your doctor may have prescribed it skin information. It does not take the for another reason. • dizziness or light-headedness place of talking to your doctor or This medicine is not addictive. • back pain pharmacist. This medicine is available only with Do not use DBL Docetaxel, All medicines have risks and a doctor’s prescription. benefits. Your doctor has weighed Concentrated Injection if you have, You may have taken another the risks of you taking DBL or have had, any of the following Docetaxel, Concentrated Injection medicine to treat your breast, non medical conditions: small cell lung cancer, ovarian, against the benefits they expect it • severe liver problems prostate or head and neck cancer. will have for you. • blood disorder with a reduced However, your doctor has now number of white blood cells If you have any concerns about decided to treat you with docetaxel. taking this medicine, ask your There is not enough information to Do not use this medicine if you are doctor or pharmacist. recommend the use of this medicine pregnant or intend to become Keep this leaflet with the medicine. -

Primary Ewing Sarcoma/Primitive Neuroectodermal Tumor of the Kidney: the MD Anderson Cancer Center Experience

cancers Article Primary Ewing Sarcoma/Primitive Neuroectodermal Tumor of the Kidney: The MD Anderson Cancer Center Experience Nidale Tarek 1,2,*, Rabih Said 3, Clark R. Andersen 4, Tina S. Suki 1, Jessica Foglesong 1,5 , Cynthia E. Herzog 1, Nizar M. Tannir 6, Shreyaskumar Patel 7, Ravin Ratan 7, Joseph A. Ludwig 7 and Najat C. Daw 1,* 1 Department of Pediatrics, the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX 77030, USA; [email protected] (T.S.S.); [email protected] (J.F.); [email protected] (C.E.H.) 2 Department of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, American University of Beirut Medical Center, Beirut 1107, Lebanon 3 Department of Investigational Cancer Therapeutics, the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX 77030, USA; [email protected] 4 Department of Biostatistics, the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX 77030, USA; [email protected] 5 Division of Hematology, Oncology, Neuro-Oncology & Stem Cell Transplant, Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, Chicago, IL 60611, USA 6 Department of Genitourinary Medical Oncology, the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX 77030, USA; [email protected] 7 Department of Sarcoma Medical Oncology, the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX 77030, USA; [email protected] (S.P.); [email protected] (R.R.); [email protected] (J.A.L.) * Correspondence: [email protected] (N.T.); [email protected] (N.C.D.); Tel.: +1-713-792-6620 (N.C.D.) Received: 27 August 2020; Accepted: 5 October 2020; Published: 11 October 2020 Simple Summary: The Ewing sarcoma family of tumors (ESFT)s rarely originate in the kidneys and their treatment is significantly different from the other common kidney tumors. -

Pathogenesis and Current Treatment of Osteosarcoma: Perspectives for Future Therapies

Journal of Clinical Medicine Review Pathogenesis and Current Treatment of Osteosarcoma: Perspectives for Future Therapies Richa Rathore 1 and Brian A. Van Tine 1,2,3,* 1 Division of Medical Oncology, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO 63110, USA; [email protected] 2 Division of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology, St. Louis Children’s Hospital, St. Louis, MO 63110, USA 3 Siteman Cancer Center, St. Louis, MO 63110, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Osteosarcoma is the most common primary malignant bone tumor in children and young adults. The standard-of-care curative treatment for osteosarcoma utilizes doxorubicin, cisplatin, and high-dose methotrexate, a standard that has not changed in more than 40 years. The development of patient-specific therapies requires an in-depth understanding of the unique genetics and biology of the tumor. Here, we discuss the role of normal bone biology in osteosarcomagenesis, highlighting the factors that drive normal osteoblast production, as well as abnormal osteosarcoma development. We then describe the pathology and current standard of care of osteosarcoma. Given the complex hetero- geneity of osteosarcoma tumors, we explore the development of novel therapeutics for osteosarcoma that encompass a series of molecular targets. This analysis of pathogenic mechanisms will shed light on promising avenues for future therapeutic research in osteosarcoma. Keywords: osteosarcoma; mesenchymal stem cell; osteoblast; sarcoma; methotrexate Citation: Rathore, R.; Van Tine, B.A. Pathogenesis and Current Treatment of Osteosarcoma: Perspectives for Future Therapies. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 1. Introduction 10, 1182. https://doi.org/10.3390/ Osteosarcomas are the most common pediatric and adult bone tumor, with more than jcm10061182 1000 new cases every year in the United States alone. -

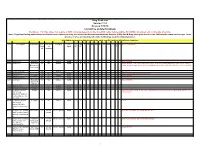

Drug Code List Version 11.4 Revised 5/18/18 List Will Be Updated Routinely

Drug Code List Version 11.4 Revised 5/18/18 List will be updated routinely Disclaimer: For drug codes that require an NDC, coverage depends on the drug NDC status (rebate eligible, Non-DESI, non-termed, etc) on the date of service. Note: Physician/Facility-administered medications are reimbursed using the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Part B Drug pricing file found on the CMS website--www.cms.hhs.gov. In the absence of a fee, pricing may reflect the methodolgy used for retail pharmacies. Highlights represent updated material for each specific revision of the Drug Code List. Code Description Brand Name NDC NDC unit Category Service AC CAH P NP MW MH HS PO OPH HI IDT DC Special Instructions Requir of Limits OP OP F ed measure 90281 human ig, im Gamastan Yes ML Antisera NONE X X X X Closed 3/31/13. 90283 human ig, iv Gamimune, Yes ML Antisera NONE X X X X Closed 3/31/13. Cost invoice required with claim. Restricted to ICD-9 diagnoses codes 204.10 - 204.12, Flebogamma, 279.02, 279.04, 279.06, 279.12, 287.31, and 446.1, and must be included on claim form, effective 10/1/09. Gammagard 90287 botulinum antitoxin N/A Antisera Not Covered 90288 botulism ig, iv No ML NONE X X X X Requires documentation and medical review 90291 cmv ig, iv Cytogam Yes ML Antisera NONE X X X X Closed 3/31/13. 90296 diphtheria antitoxin No ML NONE X X X X 90371 hep b ig, im Bayhep B, Yes ML Antisera NONE X X X X Closed 3/31/13. -

The Role of Cytogenetics and Molecular Diagnostics in the Diagnosis of Soft-Tissue Tumors Julia a Bridge

Modern Pathology (2014) 27, S80–S97 S80 & 2014 USCAP, Inc All rights reserved 0893-3952/14 $32.00 The role of cytogenetics and molecular diagnostics in the diagnosis of soft-tissue tumors Julia A Bridge Department of Pathology and Microbiology, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE, USA Soft-tissue sarcomas are rare, comprising o1% of all cancer diagnoses. Yet the diversity of histological subtypes is impressive with 4100 benign and malignant soft-tissue tumor entities defined. Not infrequently, these neoplasms exhibit overlapping clinicopathologic features posing significant challenges in rendering a definitive diagnosis and optimal therapy. Advances in cytogenetic and molecular science have led to the discovery of genetic events in soft- tissue tumors that have not only enriched our understanding of the underlying biology of these neoplasms but have also proven to be powerful diagnostic adjuncts and/or indicators of molecular targeted therapy. In particular, many soft-tissue tumors are characterized by recurrent chromosomal rearrangements that produce specific gene fusions. For pathologists, identification of these fusions as well as other characteristic mutational alterations aids in precise subclassification. This review will address known recurrent or tumor-specific genetic events in soft-tissue tumors and discuss the molecular approaches commonly used in clinical practice to identify them. Emphasis is placed on the role of molecular pathology in the management of soft-tissue tumors. Familiarity with these genetic events -

Imaging of Pediatric MSK Tumors

Imaging of Pediatric MSK Tumors Kirsten Ecklund, M.D. Boston Children’s Hospital Harvard Medical School [email protected] Tumor Imaging Goals Diagnosis Treatment Surveillance • Lesion • Size, extent • Local recurrence characterization • Treatment response • Metastatic search • Benign vs malignant – Tissue characterization • DDX (necrosis vs growth) – RECIST guidelines • Extent of disease • Surgical planning – Relationship to neurovascular structures – Measurements for custom reconstruction Current MR Imaging Goals • Highest resolution – even at small FOV • Tissue characterization – Functional imaging – Metabolic imaging • Decrease sedation – Motion correction • Increase acquisition speed Diagnosis: Normal RM Stress fx EWS Leukemia Tumor Mimics/Pitfalls • Inflammatory lesions – Osteoid osteoma – Chondroblastoma – Infection – Myositis ossificans – Histiocytosis – CRMO (CNO) • Trauma/stress fracture 19 y.o. right elbow mass Two 15 year olds with rt knee pain D. Femur stress fx, p. tibia stress reaction Primary bone lymphoma Primary Osseous Lymphoma • 6% of 1° bone tumors, <10% of NHL • Commonly involves epiphyses and equivalents • MR - “Infarct-like” appearance, sequestra • 10-30% multifocal • 10-15% metastases at dx 90% of malignant pediatric bone tumors Osteosarcoma ES family of tumors • ~ 400 new cases/yr in U.S. • ~ 200 new cases/yr • #1 malignant bone tumor < 18 y.o. • Caucasian predominance • Peak age: 13-16 y.o., boys > girls • Peak age: 10-15 y.o • Sites: d. femur (75%), p. tibia, p. • Sites: axial (54%), appendicular -

A Rare Case of Peripheral Primitive Neuroectodermal Tumor in Palate

Surgery and Rehabilitation Case Report ISSN: 2514-5959 A rare case of peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor in palate Rajul Ranka1*, Anuj Jain2, Amol Gadbail3 and Minal Chaudhary1 1Oral Pathology and Microbiology, Sharad Pawar Dental College and Hospital, Sawangi(M), Wardha, India 2Department of Trauma and Emergency Medicine, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Bhopal, India 3Department of Dentistry, Indira Gandhi Government Medical College, Nagpur, India Abstract Primitive Neuroectodermal Tumor (PNET) is an aggressive round cell malignant tumor which belongs to Ewing’s Sarcoma family. Peripheral PNET is rare in head and neck region and even rare in palate with handful of cases reported till date. A case of Peripheral PNET of palate in a 32-year-old female pa tient along with its clinico-pathologic, radiologic and immunohistologic features as well as its management is reported here. We emphasize the need of histopathology and immunohistochemistry (IHC) for early diagnosis of such aggressive tumors to improve the prognosis of patient by providing timely management. Introduction Case report A neuroectodermal tumor is a tumor of the central or peripheral A thirty-two years old female patient of Indian origin reported nervous system. They are divided into two categories viz. Group to the Out-Patient Department of our institute with a complaint of (I) tumors, such as the pituitary adenomas and carcinoid tumors, painful ulcer on her palate since five months. The ulcer was gradually represent tumors that show predominantly epithelial differenti ation. progressive but has now suddenly increased in size since few days. It Group (II) tumors, which incorporate malignant melanoma, olfactory was associated with dull aching, intermittent and localized pain which neuroblastoma, Ewing’s sar coma (EWS) and primitive neuroectodermal aggravated on mastication and relieved with time. -

Pharmaceutical Appendix to the Tariff Schedule 2

Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2007) (Rev. 2) Annotated for Statistical Reporting Purposes PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE HARMONIZED TARIFF SCHEDULE Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2007) (Rev. 2) Annotated for Statistical Reporting Purposes PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE TARIFF SCHEDULE 2 Table 1. This table enumerates products described by International Non-proprietary Names (INN) which shall be entered free of duty under general note 13 to the tariff schedule. The Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) registry numbers also set forth in this table are included to assist in the identification of the products concerned. For purposes of the tariff schedule, any references to a product enumerated in this table includes such product by whatever name known. ABACAVIR 136470-78-5 ACIDUM LIDADRONICUM 63132-38-7 ABAFUNGIN 129639-79-8 ACIDUM SALCAPROZICUM 183990-46-7 ABAMECTIN 65195-55-3 ACIDUM SALCLOBUZICUM 387825-03-8 ABANOQUIL 90402-40-7 ACIFRAN 72420-38-3 ABAPERIDONUM 183849-43-6 ACIPIMOX 51037-30-0 ABARELIX 183552-38-7 ACITAZANOLAST 114607-46-4 ABATACEPTUM 332348-12-6 ACITEMATE 101197-99-3 ABCIXIMAB 143653-53-6 ACITRETIN 55079-83-9 ABECARNIL 111841-85-1 ACIVICIN 42228-92-2 ABETIMUSUM 167362-48-3 ACLANTATE 39633-62-0 ABIRATERONE 154229-19-3 ACLARUBICIN 57576-44-0 ABITESARTAN 137882-98-5 ACLATONIUM NAPADISILATE 55077-30-0 ABLUKAST 96566-25-5 ACODAZOLE 79152-85-5 ABRINEURINUM 178535-93-8 ACOLBIFENUM 182167-02-8 ABUNIDAZOLE 91017-58-2 ACONIAZIDE 13410-86-1 ACADESINE 2627-69-2 ACOTIAMIDUM 185106-16-5 ACAMPROSATE 77337-76-9