CAS LX 500 A1 Language Acquisition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LIST of ATTORNEYS the U.S. Embassy Jakarta, Indonesia

Page 1 of 12 LIST OF ATTORNEYS The U.S. Embassy Jakarta, Indonesia assumes no responsibility or liability for the professional ability or reputation of, or the quality of services provided by, the following persons or firms. Inclusion on this list is in no way an endorsement by the Department of State or the U.S. Embassy/Consulate. Names are listed alphabetically, and the order in which they appear has no other significance. The information in the list on professional credentials, areas of expertise and language ability are provided directly by the lawyers. AFDHAL & DEDY LAW FIRM Address: Jl. KS Tubun III No. 20, Slipi, Jakarta Barat 11410 Telephone: (62-21) 5306885, Afdhal Muhammad +62 81381530266 or +62 87877823300; Fax: +62 21 53652210. E-mail: [email protected] ANDRYAWAL SIMANJUNTAK & PARTNERS Address: Komplek. Kejaksaan Agung, Blok : A1 No. 23, JL. Cipunagara I, Ciputat 15411. Telephone: (62-21) 99560888, (62)81399960888; Web site: www.andryawal.blogspot.com E-mail : [email protected] Expertise: This law firm’s area practice include litigation, non litigation, bankruptcy, corporate, commercial, labour, capital & finance, banking, criminal law, family law, administration law, immigration, foreign investment, land matter. ARMILA & RAKO Address: Suite 12-C, 12th Floor, Lippo Kuningan, Jl. H.R. Rasuna Said Kav.12, Jakarta 12920 Telephone: +62 21 2911 0015; Mobile +62 811 935503; Fax: +62 21 2911 0016 Contact person: Michel A. Rako, e-maill: [email protected] List of membership: - Co-Chairman Commercial Law Commission of International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) Indonesia - Vice Secretary General of the Indonesian Academy of Independent Mediators and Arbitrators (MedArbId) - Member of Indonesian BAR Association (PERADI) Expertise: Litigation and Dispute Resolution, Mining and Energy,Corporate and Commercial, Merger and Acquisition, Foreign Investment, Employment, Intellectual Property Rights. -

The Java® Language Specification Java SE 8 Edition

The Java® Language Specification Java SE 8 Edition James Gosling Bill Joy Guy Steele Gilad Bracha Alex Buckley 2015-02-13 Specification: JSR-337 Java® SE 8 Release Contents ("Specification") Version: 8 Status: Maintenance Release Release: March 2015 Copyright © 1997, 2015, Oracle America, Inc. and/or its affiliates. 500 Oracle Parkway, Redwood City, California 94065, U.S.A. All rights reserved. Oracle and Java are registered trademarks of Oracle and/or its affiliates. Other names may be trademarks of their respective owners. The Specification provided herein is provided to you only under the Limited License Grant included herein as Appendix A. Please see Appendix A, Limited License Grant. To Maurizio, with deepest thanks. Table of Contents Preface to the Java SE 8 Edition xix 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Organization of the Specification 2 1.2 Example Programs 6 1.3 Notation 6 1.4 Relationship to Predefined Classes and Interfaces 7 1.5 Feedback 7 1.6 References 7 2 Grammars 9 2.1 Context-Free Grammars 9 2.2 The Lexical Grammar 9 2.3 The Syntactic Grammar 10 2.4 Grammar Notation 10 3 Lexical Structure 15 3.1 Unicode 15 3.2 Lexical Translations 16 3.3 Unicode Escapes 17 3.4 Line Terminators 19 3.5 Input Elements and Tokens 19 3.6 White Space 20 3.7 Comments 21 3.8 Identifiers 22 3.9 Keywords 24 3.10 Literals 24 3.10.1 Integer Literals 25 3.10.2 Floating-Point Literals 31 3.10.3 Boolean Literals 34 3.10.4 Character Literals 34 3.10.5 String Literals 35 3.10.6 Escape Sequences for Character and String Literals 37 3.10.7 The Null Literal 38 3.11 Separators -

Boyzone ...By Request Mp3, Flac, Wma

Boyzone ...By Request mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Pop Album: ...By Request Country: Italy Released: 1999 Style: Vocal, Ballad MP3 version RAR size: 1619 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1206 mb WMA version RAR size: 1166 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 402 Other Formats: ADX AC3 MP1 AHX AUD FLAC AIFF Tracklist Hide Credits I Love The Way You Love Me A1 –Boyzone 3:46 Written By – Victoria Shaw , Chuck Cannon No Matter What Producer [Music] – Andrew Lloyd Webber, Jim Steinman, Nigel A2 –Boyzone 4:34 WrightWritten By [Lyrics] – Jim SteinmanWritten By [Music] – Andrew Lloyd Webber All That I Need A3 –Boyzone Producer, Arranged By – Carl Sturken, Evan RogersWritten By – Evan 3:42 Rogers , Carl Sturken Baby Can I Hold You A4 –Boyzone 3:15 Producer – Stephen LipsonWritten By – Tracy Chapman Picture Of You A5 –Boyzone 3:29 Producer – Absolute Written By – Watkins/Wilson/Kennedy/Keating Isn't It A Wonder A6 –Boyzone 3:45 Written By – Keating/Hedges/Brannigan A Different Beat A7 –Boyzone 4:15 Written By – Keating/Gately/Lynch/Duffy/Brannigan/Hedges Words A8 –Boyzone Producer – Phil Harding & Ian CurnowWritten By – Barry Gibb , Maurice 4:04 Gibb , Robin Gibb Father And Son A9 –Boyzone 2:46 Written By – Cat Stevens So Good B1 –Boyzone 3:03 Written By – Duffy/Gately/Graham/Keating/Lynch/Hedges/Brannigan Coming Home Now B2 –Boyzone 3:45 Written By – Duffy/Gately/Graham/Keating/Lynch/Hedges/Brannigan Key To My Life B3 –Boyzone 3:45 Written By – Gately/Graham/Keating/Hedges/Brannigan Love Me For A Reason B4 –Boyzone 3:39 Written By – John Bristol , Wade Brown , David Jr. -

Song Title Version 1 More Time Daft Punk 5,6,7,8 Steps All 4 L0ve Color Me Badd All F0r Y0u Janet Jackson All That I Need Boyzon

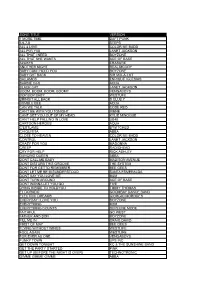

SONG TITLE VERSION 1 MORE TIME DAFT PUNK 5,6,7,8 STEPS ALL 4 L0VE COLOR ME BADD ALL F0R Y0U JANET JACKSON ALL THAT I NEED BOYZONE ALL THAT SHE WANTS ACE OF BASE ALWAYS ERASURE ANOTHER NIGHT REAL MCCOY BABY CAN I HOLD YOU BOYZONE BABY G0T BACK SIR MIX-A-LOT BAILAMOS ENRIQUE IGLESIAS BARBIE GIRL AQUA BLACK CAT JANET JACKSON BOOM, BOOM, BOOM, BOOM!! VENGABOYS BOP BOP BABY WESTUFE BRINGIT ALL BACK S CLUB 7 BUMBLE BEE AQUA CAN WE TALK CODE RED CAN'T BE WITH YOU TONIGHT IRENE CANT GET YOU OUT OF MY HEAD KYLIE MINOGUE CAN'T HELP FALLING IN LOVE UB40 CARTOON HEROES AQUA C'ESTLAVIE B*WITCHED CHIQUITITA ABBA CLOSE TO HEAVEN COLOR ME BADD CONTROL JANET JACKSON CRAZY FOR YOU MADONNA CREEP RADIOHEAD CRY FOR HELP RICK ASHLEY DANCING QUEEN ABBA DONT CALL ME BABY MADISON AVENUE DONT DISTURB THIS GROOVE THE SYSTEM DONT FOR GETTO REMEMBER BEE GEES DONT LET ME BE MISUNDERSTOOD SANTA ESMERALDA DONT SAY YOU LOVE ME M2M DONT TURN AROUND ACE OF BASE DONT WANNA LET YOU GO FIVE DYING INSIDE TO HOLDYOU TIMMY THOMAS EL DORADO GOOMBAY DANCE BAND ELECTRIC DREAMS GIORGIO MORODES EVERYDAY I LOVE YOU BOYZONE EVERYTHING M2M EVERYTHING COUNTS DEPECHE MODE FAITHFUL GO WEST FATHER AND SON BOYZONE FILL ME IN CRAIG DAVID FIRST OF MAY BEE GEES FLYING WITHOUT WINGS WESTLIFE FOOL AGAIN WESTLIFE FOR EVER AS ONE VENGABOYS FUNKY TOWN UPS INC GET DOWN TONIGHT KC & THE SUNSHINE BAND GET THE PARTY STARTED PINK GET UP (BEFORE THE NIGHT IS OVER) TECHNOTRONIC GIMME GIMME GIMME ABBA HAPPY SONG BONEY M. -

Flames Damage Cars 'She Never Lost Her Optinitiata I M4111:111 Said

SPARTAN D4II4Y VOLUME 125, NUMBER 56 Serving San Jose State Cniversity sitise 1934 \ VI:DNESDAY, DECEMBER 7. 2005 Supergrass CD,Re\ iev Dieting done right A&E"-tle 7 _ , " Opinion Page 2 Seventh Street garage fire Philosophy prof. to be remembered BY JOHN MYERS -"cs,! . Ruth Math, ties cr lett her. not even after becoming ill with an i nun tmitt,' sy stein disease. "()ite ot the last e mails she sent nie was one that -aid. 'I has e no immune isc l'in great.... said Rita rvlanning, chair of the philosoph department al San Jose State I nisersity Manor. a tinnier 5.111I philosoph prolessor. shed Nuns 13 in 'ICI Avis. Israel. at the disease %it'll., slow n her body's natural defenses. She had taught In philosophy at SJSII since 1981 and also taught classes an tel As is Iniversity. The philossphy department v% ill be holding a memo rial ser% ice for Manor at I p.m. Friday at the Spartan Memorial. "She 110 er slid quit working." Manning said "When she ..is at Kaiser hospital lint San Jose'. in miens's,- care. she insisted on bringing her laptop." \lainor sets cd :is interim chair ot the pltilo,opliv the imminent on two separate k ill 10K8 and (102 said -support coonlina tor for IIIC She s tmnui .n said. -AllII1111!2 111.11 Canis' lip 55.15 IICScl .1 Crusts .IISSfIS had a ere e, posit is e ss,ms tnt 1., ,king. it. - DIANA DIHOY DAILY SIAFF I oil Taidittan. .1,1111)2 associate dean of the College of San Jose Fire Department Captain Angela Jacobs writes down the license plate numbers of cars that were damaged by a car that caught on Humanities and tins' Ails. -

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed up 311 Down

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed Up 311 Down 702 Where My Girls At 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 Little Bit More, A 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 10,000 Maniacs More Than This 10,000 Maniacs These Are The Days 10CC Donna 10CC Dreadlock Holiday 10CC I'm Mandy 10CC I'm Not In Love 10CC Rubber Bullets 10CC Things We Do For Love, The 10CC Wall Street Shuffle 112 & Ludacris Hot & Wet 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac Thugz Mansion 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Duck & Run 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Its not my time 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down Loser 3 Doors Down Road I'm On, The 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 38 Special If I'd Been The One 38 Special Second Chance 3LW I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) 3LW No More 3LW No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) 3LW Playas Gon' Play 3rd Strike Redemption 3SL Take It Easy 3T Anything 3T Tease Me 3T & Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Stairsteps Ooh Child 50 Cent Disco Inferno 50 Cent If I Can't 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent P.I.M.P. (Radio Version) 50 Cent Wanksta 50 Cent & Eminem Patiently Waiting 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 21 Questions 5th Dimension Aquarius_Let the sunshine inB 5th Dimension One less Bell to answer 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up & Away 5th Dimension Wedding Blue Bells 5th Dimension, The Last Night I Didn't Get To Sleep At All 69 Boys Tootsie Roll 8 Stops 7 Question -

A 3Rd Strike No Light a Few Good Men Have I Never a Girl Called Jane

A 3rd Strike No Light A Few Good Men Have I Never A Girl Called Jane He'S Alive A Little Night Music Send In The Clowns A Perfect Circle Imagine A Teens Bouncing Off The Ceiling A Teens Can't Help Falling In Love With You A Teens Floor Filler A Teens Halfway Around The World A1 Caught In The Middle A1 Ready Or Not A1 Summertime Of Our Lives A1 Take On Me A3 Woke Up This Morning Aaliyah Are You That Somebody Aaliyah At Your Best (You Are Love) Aaliyah Come Over Aaliyah Hot Like Fire Aaliyah If Your Girl Only Knew Aaliyah Journey To The Past Aaliyah Miss You Aaliyah More Than A Woman Aaliyah One I Gave My Heart To Aaliyah Rock The Boat Aaliyah Try Again Aaliyah We Need A Resolution Aaliyah & Tank Come Over Abandoned Pools Remedy ABBA Angel Eyes ABBA As Good As New ABBA Chiquita ABBA Dancing Queen ABBA Day Before You Came ABBA Does Your Mother Know ABBA Fernando ABBA Gimmie Gimmie Gimmie ABBA Happy New Year ABBA Hasta Manana ABBA Head Over Heels ABBA Honey Honey ABBA I Do I Do I Do I Do I Do ABBA I Have A Dream ABBA Knowing Me, Knowing You ABBA Lay All Your Love On Me ABBA Mama Mia ABBA Money Money Money ABBA Name Of The Game ABBA One Of Us ABBA Ring Ring ABBA Rock Me ABBA So Long ABBA SOS ABBA Summer Night City ABBA Super Trouper ABBA Take A Chance On Me ABBA Thank You For The Music ABBA Voulezvous ABBA Waterloo ABBA Winner Takes All Abbott, Gregory Shake You Down Abbott, Russ Atmosphere ABC Be Near Me ABC Look Of Love ABC Poison Arrow ABC When Smokey Sings Abdul, Paula Blowing Kisses In The Wind Abdul, Paula Cold Hearted Abdul, Paula Knocked -

Refeeding with Free Lactose Milk ( A1 - 110 Nestle ) in Children Suffering from Gastroenteritis and Dehydration

Paediatrica Indonesiana 15 : 191 — 197. July — August 1975. 191 From the Department of Child Health, Medical School, University of Indonesia, Jakarta. Refeeding with Free Lactose Milk ( A1 - 110 Nestle ) in Children Suffering from Gastroenteritis and Dehydration by SUHARJONO, SUNOTO, ASWITHA BOEDIARSO, HENTYANTO HENDARDJI and SOEG1HARTO. Abstract Forty one infants suffering from diarrhoea hospitalized in the Department of Child Health, Medical School, University of lndonesia/Dr. Tjipto Man gun- husumo General Hospital, Jakarta, from August 15, 1973 to January 15, 1974 were refed with ’’free lactose milk”. The result is as follows : 1. From the point of view of increase of body weight: 27 (65.8 % ) out of 41 cases were excellent. 2 ( 4.9 % ) out of 41 cases were good. 12 (29.3 % ) out of41 cases were poor. 2 From the point of view of stopping the diarrhoea : 25 (60.9 % ) out of 41 cases were excellent. 10 (24.5 % ) out of 41 was good. 6 (14.6 % ) out of 41 cases were poor. Reotsived 2nd M ay 1975. 192 SUHARJONO ET AL Small bowell biopsy from children water 2.9 gm with gastroenteritis often demon calories 480 or 670 cal/L. strates histologically the presence of Starting the regimentation and villous atrophy (Walker Smith, 1969, adaptation we used dilution of 1/3 1972) which may lead to secondary this formula which was increased sugar intolerance (Dahlqvist et al., daily until ilt reached the proper dilu 1970; Sunoto et al., 1973). tion adapted to the requirement of the child. Antibiotic treatment and refeeding After 3 consecutive days the proper with normal milk formula consisting dilution of Al-110, S.G.M. -

In Albums Released 58Only Albums Have Been Certified

LABELS at WORK In only albums have 150,000 been certified 2017 albums released 58 1/1/2017-6/13/2018 LEVEL REL DATE TITLE ARTIST LABEL GENRE CERT DATE 3/3/2017 ÷ Ed Sheeran Atlantic Records Pop 3/22/2017 11/10/2017 Reputation Taylor Swift Big Machine Records Pop 12/11/2017 Top Dawg Entertainment/ R&B/ 4/14/2017 Damn. Kendrick Lamar 5/20/2017 Aftermath/Interscope Records Hip Hop R&B/ 2/17/2017 I Decided Big Sean Def Jam Recordings 4/18/2017 Hip Hop 1/12/2018 Camila Camila Cabello Epic Pop 1/22/2018 R&B/ 10/31/2017 Heartbreak On A Full Moon Chris Brown RCA 11/8/2017 Hip Hop R&B/ 6/23/2017 Grateful DJ Khaled Epic 7/14/2017 Hip Hop R&B/ 2/17/2017 Future Future Epic 4/25/2017 Hip Hop 6/2/2017 Hopeless Fountain Kingdom Halsey Astralwerks Pop 5/18/2018 6/23/2017 Evolve Imagine Dragons Kidinacorner/Interscope Rock 7/28/2017 R&B/ 6/30/2017 4:44 Jay-Z Roc Nation 7/5/2017 Hip Hop R&B/ 3/3/2017 American Teen Khalid Right Hand Music/RCA 6/23/2017 Hip Hop R&B/ 8/25/2017 Luv Is Rage 2 Lil Uzi Vert Atlantic Records 10/13/2017 Hip Hop R&B/ 6/30/2017 Everybody Logic Def Jam 8/17/2017 Hip Hop 11/3/2017 Red Pill Blues Maroon 5 222 Records/Interscope Pop 5/17/2018 Quality Control Music/ R&B/ 1/27/2017 Culture Migos 7/14/2017 300 Entertainment Hip Hop Quality Control Music/ R&B/ 1/26/2018 Culture II Migos 5/10/2018 Motown Hip Hop 11/13/2017 Beautiful Trauma P!nk RCA Pop 4/19/2018 R&B/ 4/27/2018 Beerbongs & Bentleys Post Malone Republic Records 4/30/2018 Hip Hop R&B/ 5/5/2017 There’s Really A Wolf Russ Columbia/Russ My Way Inc 4/18/2018 Hip Hop Top Dawg Entertainment/ -

Colonel Samuel Smith Park Study Area

Colonel Samuel Smith Park Study Area Terrestrial Biological Inventory and Assessment April, 2014 C o l o n e l S a m u e l S m i t h P a r k S t u d y A r e a April, 2014 Report prepared by: Paul Prior, Fauna Biologist Natasha Gonsalves, Environmental Technician Alberta D’Souza, GIS Technologist Reviewed by: Sue Hayes, Project Manager, Terrestrial Field Inventories Scott Jarvie, Manager, Watershed Monitoring and Reporting Section This report may be referenced as: Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (TRCA). 2014. Colonel Samuel Smith Park Study Area Terrestrial Biological Inventory and Assessment. C o l o n e l S a m u e l S m i t h P a r k S t u d y A r e a April, 2014 Table of Contents page 1.0 Introduction ............................................................................................. 1 1.1 TRCA’s Terrestrial Natural Heritage Program ................................................................. 1 2.0 Study Area Description .......................................................................... 2 3.0 Inventory Methodology ......................................................................... 3 3.1 Landscape Analysis ........................................................................................................ 3 3.2 Vegetation Community and Species ............................................................................... 5 4.0 Results and Discussion ........................................................................ 6 4.1 Regional Context ............................................................................................................ -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2013/0237454 A1 Schutzer (43) Pub

US 2013 0237454A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2013/0237454 A1 Schutzer (43) Pub. Date: Sep. 12, 2013 (54) DIAGNOSTIC MARKERS FOR Publication Classification NEUROPSYCHATRC DISEASE (51) Int. Cl. (76) Inventor: Steven E. Schutzer, Water Mill, NY GOIN33/68 (2006.01) (US) (52) U.S. Cl. CPC .................................. G0IN33/6896 (2013.01) (21) Appl. No.: 13/697,417 USPC ............................................................ SO6/12 (22) PCT Filed: May 12, 2011 (57) ABSTRACT Biomarkers for the diagnosis of neuropsychiatric diseases are (86). PCT No.: PCT/US11?0O843 presented herein. In particular embodiments, biomarkers are S371 (c)(1), identified that are useful for diagnosing multiple Sclerosis, (2), (4) Date: May 23, 2013 chronic fatigue syndrome, or Neurologic Lyme disease. Also encompassed is a method for diagnosing a patient with a Related U.S. Application Data neuropsychiatric disease. Such as multiple Sclerosis, chronic AV fatigue syndrome, or Neurologic Lyme disease, by analyzing (60) Provisional application No. 61/395,354, filed on May biological samples isolated from the patient or the patient as 12, 2010. a whole to assess levels of the biomarkers described herein. -N- 1895 72% 63 735 8% 92% Patent Application Publication Sep. 12, 2013 US 2013/0237454 A1 Figure l US 2013/0237454 A1 Sep. 12, 2013 DAGNOSTIC MARKERS FOR tiple Sclerosis is more common in women than men and NEUROPSYCHATRC DISEASE generally begins between ages 20 and 40, but can develop at any age. Multiple Sclerosis is generally viewed as an autoim FIELD OF THE INVENTION mune syndrome directed against unidentified central nervous 0001. The present invention relates to identifying biologic tissue antigens. -

The Works Brass Band – a Historical Directory of the Industrial and Corporate Patronage and Sponsorship of Brass Bands

The works brass band – a historical directory of the industrial and corporate patronage and sponsorship of brass bands Gavin Holman, January 2020 Preston Corporation Tramways Band, c. 1910 From the earliest days of brass bands in the British Isles, they have been supported at various times and to differing extents by businesses and their owners. In some cases this support has been purely philanthropic, but there was usually a quid pro quo involved where the sponsor received benefits – e.g. advertising, income from band engagements, entertainment for business events, a “worthwhile” pastime for their employees, corporate public relations and brand awareness - who would have heard of John Foster’s Mills outside of the Bradford area if it wasn’t for the Black Dyke Band? One major sponsor and supporter of brass bands, particularly in the second half of the 19th century, was the British Army, through the Volunteer movement, with upwards of 500 bands being associated with the Volunteers at some time – a more accurate estimate of these numbers awaits some further analysis. However, I exclude these bands from this paper, to concentrate on the commercial bodies that supported brass bands. I am also excluding social, civic, religious, educational and political organisations’ sponsorship or support. In some cases it is difficult to determine whether a band, composed of workers from a particular company or industry was supported by the business or not. The “workmen’s band” was often a separate entity, supported by a local trade union or other organisation. For the purposes of this review I will be including them unless there is specific reference to a trade union or other social organisation.