The War on the Rohingya by JASON SZEP, ANDREW R.C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

News Release

news release FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE PRESS CONTACT: Maggie Stapleton, Jensen Artists September 25, 2019 646.536.7864 x2; [email protected] American Composers Orchestra Announces 2019-2020 Season Derek Bermel, Artistic Director & George Manahan, Music Director Two Concerts presented by Carnegie Hall New England Echoes on November 13, 2019 & The Natural Order on April 2, 2020 at Zankel Hall Premieres by Mark Adamo, John Luther Adams, Matthew Aucoin, Hilary Purrington, & Nina C. Young Featuring soloists Jamie Barton, mezzo-soprano; JIJI, guitar; David Tinervia, baritone & Jeffrey Zeigler, cello The 29th Annual Underwood New Music Readings March 12 & 13, 2020 at Aaron Davis Hall at The City College of New York ACO’s annual roundup of the country’s brightest young and emerging composers EarShot Readings January 28 & 29, 2020 with Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra May 5 & 6, 2020 with Houston Symphony Third Annual Commission Club with composer Mark Adamo to support the creation of Last Year ACO Gala 2020 honoring Anthony Roth Constanzo, Jesse Rosen, & Yolanda Wyns March 4, 2020 at Bryant Park Grill www.americancomposers.org New York, NY – American Composers Orchestra (ACO) announces its full 2019-2020 season of performances and engagements, under the leadership of Artistic Director Derek Bermel, Music Director George Manahan, and President Edward Yim. ACO continues its commitment to the creation, performance, preservation, and promotion of music by 1 American Composers Orchestra – 2019-2020 Season Overview American composers with programming that sparks curiosity and reflects geographic, stylistic, racial and gender diversity. ACO’s concerts at Carnegie Hall on November 13, 2019 and April 2, 2020 include major premieres by 2015 Rome Prize winner Mark Adamo, 2014 Pulitzer Prize winner John Luther Adams, 2018 MacArthur Fellow Matthew Aucoin, 2017 ACO Underwood Commission winner Hilary Purrington, and 2013 ACO Underwood Audience Choice Award winner Nina C. -

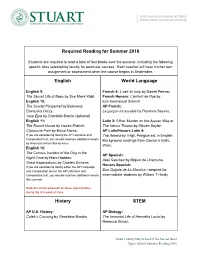

Required Reading for Summer 2016 English World Language

Required Reading for Summer 2016 Students are required to read a total of four books over the summer, including the following specific titles selected by faculty for particular courses. Each teacher will have his/her own assignment or assessment when the course begins in September. English World Language English 9: French 4: L’oeil du loup by Daniel Pennac The Secret Life of Bees by Sue Monk Kidd. French Honors: L’enfant de Noe by English 10: EricEmmanuel Schmitt. The Scarlet Pimpernel by Baroness AP French: Emmuska Orczy. Le garçon incassable by Florence Seyvos. Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte (optional) English 11: Latin 3: Either Murder on the Appian Way or The Round House by Louise Erdrich. The Venus Throws by Steven Saylor. Clybourne Park by Bruce Norris. AP Latin/Honors Latin 4: If you are considering taking the AP Literature and The Aeneid by Virgil, Penguin ed. in English. Composition test, you should read two additional novels Background readings from Caesar’s Gallic by American writers this summer. Wars. English 12: The Curious Incident of the Dog in the AP Spanish: NightTime by Mark Haddon. Abel Sanchez by Miguel de Unamuno. Great Expectations by Charles Dickens Honors Spanish: If you are considering taking either the AP Language Don Quijote de La Mancha adapted for and Composition test or the AP Literature and Composition test, you should read two additional novels intermediate students by William T Hardy. this summer. Students will be assessed on these required titles during the first week of class. History STEM AP U.S. -

Download Our 2021 Empower Luncheon

APRIL IS SEXUAL ASSAULT AWARENESS MONTH PROGRAM 11:30 a.m. – Event Begins • Welcome by Toya Washington, WISN 12 News Anchor 11:45 a.m. – Remarks by Angela Mancuso, Executive Director 12:00 p.m. – Keynote • A Conversation with Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey 12:15 p.m. – Moderated Q & A - with Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey • Moderated by Toya Washington, WISN 12 News Anchor Advocates are available on our Hotline throughout the event should anyone find these remarks triggering and want support. 24-Hour Hotline: 262.542.3828 DONATE TODAY! Your support ensures we can continue providing vital programs and services for survivors. twcwaukesha.org/donate A MESSAGE FROM OUR EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Thank you for being here with us today. The EmPower Luncheon is each year, a time for all of us to come together and reaffirm our commitment to standing with survivors, to break down pervasive myths and miscon- ceptions, and to learn how we can all join together to prevent sexual assault and abuse. Your support of The Women’s Center and this event – our largest fundraiser of the year – is what makes our work possible, and the proceeds directly benefit survivors by helping them find safety, shelter, and support when they enter our doors or call our 24-Hour Hotline. Two women who have dedicated much of the last 5 years to uncovering the lengths powerful abusers will go to silence their victims and prevent survivors from speaking up are Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey. In their book, She Said: Breaking the Sexual Harassment Story That Helped Ignite a Movement, they tell the story of how dozens of women stood together and brought down Hollywood mogul Harvey Weinstein and uncovered countless other predatory men working in Hollywood. -

Anthony Lewis: What He Learned at Harvard Law School

Missouri Law Review Volume 79 Issue 4 Fall 2014 Article 4 Fall 2014 Anthony Lewis: What He Learned at Harvard Law School Lincoln Caplan Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/mlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Lincoln Caplan, Anthony Lewis: What He Learned at Harvard Law School, 79 MO. L. REV. (2014) Available at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/mlr/vol79/iss4/4 This Conference is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Missouri Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Caplan: Anthony Lewis: What He Learned Anthony Lewis: What He Learned at Harvard Law School Lincoln Caplan* Anthony Lewis was a columnist for The New York Times for the unusu- ally long tenure of thirty-two years.1 When he retired in 2001 at the age of seventy-four, Bill Clinton awarded him the Presidential Citizens Medal for setting “the highest standard of journalistic ethics and excellence” and for being “a clear and courageous voice for democracy and justice.”2 Lewis end- ed his last column by paraphrasing one of his heroes: “The most important office in a democracy, Justice Louis Brandeis said, is the office of citizen.”3 Lewis’ point was that the American commitment to the rule of law and the belief in reason on which it rests both depend on citizens standing up to rulers who abuse power by exercising it unreasonably – arbitrarily and unjustly.4 Lewis sounded like a classic outsider, who believed that his most im- portant job as a journalist was to be a stand-in for citizens as an adversary of the government. -

Read the Full Brief Here

USCA Case #18-5276 Document #1770356 Filed: 01/25/2019 Page 1 of 59 ORAL ARGUMENT NOT SCHEDULED No. 18-5276 _____________________________ _____________________________ JASON LEOPOLD AND REPORTERS COMMITTEE FOR FREEDOM OF THE PRESS, Appellants, v. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Appellee. ____________________________ ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA No. 1:13-mc-00712 (Howell, C.J.) BRIEF OF MEDIA ORGANIZATIONS IN SUPPORT OF APPELLANTS Laura R. Handman Selina MacLaren DAVIS WRIGHT TREMAINE LLP DAVIS WRIGHT TREMAINE LLP 1919 Pennsylvania Avenue NW 865 South Figueroa Street Suite 800 Suite 2400 Washington, D.C. 20006-3402 Los Angeles, C.A. 90017-2566 (202) 973-4200 (213) 633-8617 [email protected] [email protected] Counsel for Amici Curiae Media Organizations USCA Case #18-5276 Document #1770356 Filed: 01/25/2019 Page 2 of 59 STATEMENT REGARDING CONSENT TO FILE AND SEPARATE BRIEFING Pursuant to D.C. Circuit Rule 29(b), undersigned counsel for amici curiae media organizations represents that both parties have been sent notice of the filing of this brief and have consented to the filing.1 Pursuant to D.C. Circuit Rule 29(d), undersigned counsel for amici curiae certifies that a separate brief is necessary to provide the perspective of media organizations and reporters whose reporting depends on access to court records. Access to such records allows the press to inform the public about the judiciary, the criminal justice system, surveillance trends, and local crime. Access to the type of surveillance-related records sought here would also inform the press about when the government targets journalists for surveillance and how existing press protections, which shield journalistic work product from intrusive government surveillance, apply tojournalists’electronicdata.Amici are thus particularly well-situated to provide the Court with insight into the public interest value of unsealing court records, generally, and the surveillance-related court records requested here, in particular. -

May 17–18, 2014

B I O FIFTH ANNUAL Compleat 2014 CONFERENCEBiographer May 17–18, 2014 University of Massachusetts Boston 100 Morrissey Boulevard, Boston, Massachusetts The 2013 Plutarch Award Biographers International Organization – with the generous support of the Chappell Great Lives Program – is proud to present the Plutarch Award for the best biography of 2013, as chosen by you, the world’s only organization of biographers. Congratulations to the ten nominees for the Best Biography of 2013: The 2014 BIO Award Recipient: Stacy Schiff Stacy Schiff won the 2000 Pulitzer Prize for . Véra (Mrs. Vladimir Nabokov) She is the author as well of , a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, Saint-Exupéry and , , awarded the A Great Improvisation: Franklin France, and the Birth of America George Washington Book Prize and the Ambassador Book Award. Her most recent biography, was published in 2010. Translated Cleopatra: A Life, into 30 languages, won the PEN/Jacqueline Bograd Weld Award Cleopatra for Biography. Praised for her meticulous scholarship and her witty style, Schiff has contributed frequently to op-ed page and . She has received fellowships from the The New York Times The New York Times Book Review Guggenheim Foundation, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the Center for Scholars and Writers at the New York Public Library. The recipient of an Academy Award in Literature from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, Schiff was named a 2011 Library Lion of the New York Public Library. A native of western Massachusetts, Schiff lives in New York City. She is at work on a book about the Salem witch trials, to be published by Little, Brown. -

The Child Exchange by MEGAN TWOHEY

The Child Exchange BY MEGAN TWOHEY NOMINATION FOR THE 2014 PULITZER PRIZE CATEGORY: INVESTIGATIVE REPORTING January 17, 2014 To: The Pulitzer Prize Advisory Panel The posts were striking: “I am totally ashamed to say it but we do truly hate this boy!” one woman wrote of her 11-year-old son. Said another parent of her daughter: “I would have given her away to a serial killer, I was so desperate.” The parents weren’t simply venting. Reuters reporter Megan Twohey had discovered an underground clearinghouse of kids – a cluster of Internet bulletin boards where parents sought to get rid of children they had adopted overseas. How often was this happening, and what had become of the children? Nobody knew. Because parents handled the custody transfers privately, often with strangers they met online, no government agency was involved and none was investigating the practice, called “private re-homing.” For 18 months, Reuters committed to an inquiry so original and comprehensive that it had never been attempted – not by the government or by top researchers exploring the role of the Internet in adoption. Twohey and her colleagues sought to document illicit child-custody transfers by dissecting the little-known online bulletin boards – a marketplace we called “The Child Exchange.” What we found was “devastating,” New York Times columnist Nick Kristof noted. Parents were advertising unwanted children, often illegally, and then passing them to strangers – and bypassing the judges and social workers who serve as the safety net meant to protect children. “We learned something from this series,” said Adam Pertman of the Donaldson Adoption Institute, which had released a 70-page report in 2012 on the Internet’s impact on adoption. -

How Journalists and the Public Shape Our Democracy

HOW JOURNALISTS AND THE PUBLIC SHAPE OUR DEMOCRACY From Social Media and “Fake News” to Reporting Just the Facts HOW JOURNALISTS AND THE PUBLIC SHAPE OUR DEMOCRACY From Social Media and “Fake News” to Reporting Just the Facts Written and Researched by Marcus E. Howard Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication, University of Georgia published in association with the atlanta press club and through the support of the andrew w. mellon foundation Georgia Humanities Atlanta, Georgia © 2019 by Georgia Humanities Council All rights reserved. Published in 2019. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Marcus Howard would like to thank the University of Georgia Main Library in Athens, where much of the research was conducted, as well as the following media experts and professionals who provided sub- stantial assistance: Carolyn Carlson, Kennesaw State University pro- fessor of communication and retired journalism program director; Nathaniel J. Evans, University of Georgia assistant professor of adver- tising; Keith L. Herndon, University of Georgia professor of prac- tice in journalism and director of the James M. Cox Jr. Institute for Journalism, Innovation, Management and Leadership; Peter Charles Hoffer, University of Georgia Distinguished Research Professor of History; Janice Hume, the Carolyn McKenzie and Don E. Carter Chair for Excellence in Journalism at the University of Georgia; Monica Kaufman Pearson, retired WSB-TV Atlanta news anchor; Jonathan Peters, University of Georgia assistant professor of journal- ism and communication law; Adam Ragusea, journalist in residence and visiting assistant professor at the Mercer University Center for Collaborative Journalism; Christina C. Smith, Georgia College assis- tant professor of mass communication; and Sonja R. West, the Otis Brumby Distinguished Professor of First Amendment Law at the University of Georgia. -

Symphonic Statements

Symphonic Statements Orchestras and composers are ymphony orchestras aren’t taught to be rugged, though that’s what responding to world events with new Swas required of the percussion- ists of the San Diego Symphony in Janu- scores. And in today’s political climate, ary when they played along an area of the older works are sometimes taking on Mexico-U.S. border known as “No Man’s Land” with no easy access. new resonance. The usual concert rules didn’t apply. With American musicians and spectators by David Patrick Stearns on one side of the border and a group of Mexican percussionists and spectators on the other, John Luther Adams’s 2009 In- uksuit, a piece intended to resonate with natural surroundings, had rather more significance. Nobody said it was any kind 50 symphony SUMMER 2018 The scene at the U.S.-Mexico border in with percussion on roads where there was rise all over the world, but I’m also talk- southern California on January 27, when no guard rail.” ing about the unprecedented threat to our San Diego Symphony musicians gave a Orchestras didn’t always get out so survival as a species. How could orchestras free, binational performance of John Luther much. They tended to stay in their acous- not engage in those big questions?” Adams’s Inuksuit, a percussion work intended to be played outdoors. Mexican musicians tically appropriate concert halls, speaking Martin Luther King Jr. memorial con- simultaneously performed the score—on the universal languages that originated in pre- certs, annual traditions at some orchestras, other side of the border wall. -

Pulitzer Winner Dan Fagin to Speak at UF, Mon. Feb. 15, 2016

Pulitzer Winner Dan Fagin to Speak at UF, Mon. Feb. 15, 2016 February 11, 2016 Pulitzer Prize – Winning Journalist Dan Fagin to Discuss Connection Between Science Communication and Public Health Author Dan Fagin Science and environmental journalist Dan Fagin will give a public talk at the University of Florida the evening of February 15 on his Pulitzer Prize-winning book Toms River and the role of science journalism and communication to help the public understand the connections between public health and the environment. Fagin is a long-time environmental writer and a science- journalism professor who directs the Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program at New York University. His work appears in the New York Times, Scientific American, Nature and many other publications. Toms River: A Story of Science and Salvation was awarded the 2014 Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction for its investigative reporting on industrial pollution that ravaged a small town. The Times declared it “new classic of science reporting.” Fagin, who began his reporting career in Florida, also worked 15 years as environmental writer at Newsday, where his teams were twice Pulitzer finalists. Among many other awards, he has won the two best-known science journalism prizes in the United States: the Science Journalism Award of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and the Science in Society Award of the National Association of Science Writers. He is working on a new book about monarch butterflies in the Anthropocene. Fagin is the first in a series of Pulitzer Prize-winning journalists who will be visiting the College in commemoration of the prizes’ centennial celebration. -

Upper School Students at Stuart Are Required to Read a Total of Four Books Over the Summer

Welcome Incoming Students! Upper School Students at Stuart are required to read a total of four books over the summer. This total includes titles required by specific courses. Once you receive your course schedule, please consult the following Required Reading Chart. Note that for required summer reading books, each teacher will have his or her own assignment or assessment when the course begins in the Fall. Please choose your additional books from the complete Upper School Summer Reading List which follows the Required Reading Chart and can be found on the Library website. These titles, recommended by faculty and Library staff, include nonfiction as well as several genres of fiction. Happy reading! Warmest regards, Ms. Jillian Wolf Director of Library Services Stuart Country Day School of the Sacred Heart Upper School Summer Reading 2020 Required Reading for Summer 2020 Students are required to read a total of four books over the summer, including the following specific titles selected by faculty for particular courses. Each teacher will have his/her own assignment or assessment when the course begins in September. English World Language English 9: French 4: L’oeil du loup by Daniel Pennac I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou French 5: L’enfant de Noe by Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt English 10: Choose one - Girl in Translation by Jean Kwok AP French: Book of Unknown Americans by Le garçon incassable by Florence Seyvos Christina Henriquez *Additional work should be picked up from Mme. Hoppenot prior to Summer vacation American Literature: The Namesake by Jhumpa Lahiri AP Latin/Honors Latin 4: The Aeneid by Virgil, Penguin ed. -

Tcg Publications Catalog

TCG PUBLICATIONS CATALOG TCG BOOKS 53RD STATE PRESS AURORA METRO BOOKS CHANCE MAGAZINE LEAGUE OF PROFESSIONAL THEATRE WOMEN MARTIN E. SEGAL THEATRE CENTER PUBLICATIONS NICK HERN BOOKS OBERON BOOKS PADUA PLAYWRIGHTS PRESS PAJ PUBLICATIONS PLAYSCRIPTS, INC. PLAYWRIGHTS CANADA PRESS UBU REPERTORY THEATER PUBLICATIONS For over 50 years, Theatre Communications Group (TCG), the national organization for the American theatre, has existed to strengthen, nurture and promote the professional not-for-profit American theatre. TCG’s constituency has grown from a handful of groundbreaking theatres to nearly 700 member theatres and affiliate organizations and more than 12,000 individuals nationwide. TCG offers its members networking and knowledge-building opportunities through conferences, events, research and communications; awards grants, approximately $2 million per year, to theatre companies and individual artists; advocates on the federal level; and serves as the U.S. Center of the International Theatre Institute, connecting its constituents to the global theatre community. TCG is North America’s largest independent publisher of dramatic literature, with 13 Pulitzer Prizes for Best Play on the TCG booklist. It also publishes the award-winning AMERICAN THEATRE magazine and ARTSEARCH®, the essential source for a career in the arts. In all of its endeavors, TCG seeks to increase the organizational efficiency of its member theatres, cultivate and celebrate the artistic talent and achievements of the field and promote a larger public understanding of, and appreciation for, the theatre. For more information, visit www.tcg.org. 2-21 TCG Books is the largest trade publisher of dramatic literature in North America with a booklist that includes 13 Pulitzer Prize winners.