What the Arden School Can Teach Us: Hard Lessons in Community Building

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Water Quality Trends (1970 to 2005) Along Delaware Streams in the Delaware and Chesapeake Bay Watersheds, USA

Water Air Soil Pollut (2010) 208:345–375 DOI 10.1007/s11270-009-0172-z Water Quality Trends (1970 to 2005) Along Delaware Streams in the Delaware and Chesapeake Bay Watersheds, USA Gerald J. Kauffman & Andrew C. Belden Received: 18 February 2009 /Accepted: 23 July 2009 /Published online: 20 August 2009 # Springer Science + Business Media B.V. 2009 Abstract Water quality trends from 1970 to 2005 improving Delaware water quality stations (50) out- were defined along 30 Delaware streams in the numbered degrading stations (23) by a 2:1 margin. Delaware and Chesapeake Bay watersheds in the Since 1990, degrading water quality stations (46) USA. Water quality improved or was constant at 69% exceeded improving stations (38) mostly due to of stations since 1990 and at 80% of stations since deteriorating nitrogen levels in half of Delaware 1970/1980. Dissolved oxygen (DO) improved or was streams, a reversal from early gains achieved since constant at 73% of streams since 1990 and 32% of the 1970s. Over the last three and a half decades, streams since 1970/1980. Total suspended sediment watershed strategies have improved or preserved improved or was constant at 75% of streams since water quality along Delaware streams; however, 1990 and 100% of streams since 1970/1980. Entero- greater emphasis is needed to curb recently resurging coccus bacteria improved or remained constant at increases in nitrogen levels. 80% of streams since 1990 and 93% of streams since 1970/1980. Total Kjeldahl nitrogen improved or was Keywords Water quality. Water pollution . constant at 48% of streams since 1990 and 100% of Watershed . -

The 1693 Census of the Swedes on the Delaware

THE 1693 CENSUS OF THE SWEDES ON THE DELAWARE Family Histories of the Swedish Lutheran Church Members Residing in Pennsylvania, Delaware, West New Jersey & Cecil County, Md. 1638-1693 PETER STEBBINS CRAIG, J.D. Fellow, American Society of Genealogists Cartography by Sheila Waters Foreword by C. A. Weslager Studies in Swedish American Genealogy 3 SAG Publications Winter Park, Florida 1993 Copyright 0 1993 by Peter Stebbins Craig, 3406 Macomb Steet, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20016 Published by SAG Publications, P.O. Box 2186, Winter Park, Florida 32790 Produced with the support of the Swedish Colonial Society, Philadelphia, Pa., and the Delaware Swedish Colonial Society, Wilmington, Del. Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 92-82858 ISBN Number: 0-9616105-1-4 CONTENTS Foreword by Dr. C. A. Weslager vii Introduction 1 Chapter 1: The 1693 Census 15 Chapter 2: The Wicaco Congregation 25 Chapter 3: The Wicaco Congregation - Continued 45 Chapter 4: The Wicaco Congregation - Concluded 65 Chapter 5: The Crane Hook Congregation 89 Chapter 6: The Crane Hook Congregation - Continued 109 Chapter 7: The Crane Hook Congregation - Concluded 135 Appendix: Letters to Sweden, 1693 159 Abbreviations for Commonly Used References 165 Bibliography 167 Index of Place Names 175 Index of Personal Names 18 1 MAPS 1693 Service Area of the Swedish Log Church at Wicaco 1693 Service Area of the Swedish Log Church at Crane Hook Foreword Peter Craig did not make his living, or support his four children, during a career of teaching, preparing classroom lectures, or burning the midnight oil to grade examination papers. -

0 Survey of Investment in the Delaware River Watershed Draft January 2016 Prepared For: William Penn Foundation Philadelphia, Pe

Survey of Investment in the Delaware River Watershed Draft January 2016 Prepared for: William Penn Foundation Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Prepared by: University of Delaware Water Resources Center Newark, Delaware 0 Survey of Investment in the Delaware River Watershed Background In April 2014 the William Penn Foundation announced a $35 million multi-year initiative to protect and restore the Delaware River watershed (Figure 1), the source of drinking water for over 15 million people in Delaware, New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania including the first (New York City) and seventh largest (Philadelphia) metropolitan economies in the United States. This substantial level of private funding is designed to complement and accentuate existing watershed protection and restoration investments by Federal, state, local, nonprofit, and private organizations. The Wiliam Penn Foundation is focusing investment in the Kirkwood-Cohansey (NJ), New Jersey Highlands (NJ), Brandywine Christina (DE-PA), Upstream Suburban Philadelphia (PA), Upper Lehigh (PA), Middle Schuylkill (PA), Schuylkill Highlands (PA), and Poconos Kittatinny (PA) watershed clusters. By Federal/state compact, the Delaware River Basin Commission formally links the water resources interests of 8.2 million people governed and represented by 14 federal agencies, four states, 38 counties, 838 municipalities, and numerous nonprofit organizations in the basin (Figure 2). The University of Delaware estimated that water resources appropriations scaled to the Delaware Basin totaled $740 million in FY12 with $8 million from interstate sources (1%), $285 million in Federal funds (38%), $264 million from the states (36%), and $183 million (25%) from New York City and Philadelphia. Little is known, however, about the current and cumulative level of investment in “on-the ground” watershed protection and restoration measures by these public, private, and non-profit sources in states, counties, and watersheds throughout the Delaware Basin. -

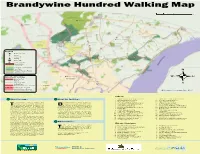

About the Facilities… About the Map… Find out More…

Brandywine Hundred Walking Map ◘Ramsey’s Farm Market ◘Highland Orchard & Market Legend Points of Interest School Historic Site T Parking Park & Ride ◘ Farmers Market Historic District Golf Course New Castle County Parkland State Park Woodlawn Trustees Property Shopping Center Little Italy Farmers Market Bike/Ped Facilities ◘ Hiking/Park Trail Sidewalk ◘Wilmington Farmers Market Planned Sidewalk Camp Fresh On Road Route ◘ Farmers Market Multi-Use Paved Trail or Bike Path ELSMERE Proposed Trail Connection Northern Delaware Greenway Brandywine Valley Scenic Byway © Delaware Greenways, Inc., 2009 About the map… About the facilities… 1 DARLEY ROAD ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 17 CARRCROFT ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 2 SPRINGER MIDDLE SCHOOL 18 A I DUPONT HIGH SCHOOL 3 TALLEY MIDDLE SCHOOL 19 SALESIANUM SCHOOL he Brandywine Hundred Walking Map randywine Hundred contains a fairly dense 4 MT PLEASANT ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 20 ST EDMONDS ACADEMY illustrates some of the many opportunities network of sidewalks and connections. 5 CLAYMONT ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 21 MT PLEASANT HIGH SCHOOL for walking and bicycling throughout and In addition, many neighborhood streets T B 6 CHARLES BUSH SCHOOL 22 WILMINGTON FRIENDS UPPER SCHOOL around Brandywine Hundred. In addition, the and regional roads are suitable for walking and map highlights some of the area’s numerous bicycling, particularly those with wide shoulders. 7 LANCASHIRE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 23 BRANDYWOOD ELEMENTARY SCHOOL recreational, cultural, and historical resources. However, not all sidewalks, connections, or road 8 TOWER HILL 24 HOLY ROSARY It is our hope that this map will assist you routes are indicated. 9 HANBY MIDDLE SCHOOL 25 CONCORD HIGH SCHOOL in finding local connections to these nearby This allows you to navigate off landmarks 10 CONCORD CHRISTIAN ACADEMY 26 ST HELENAS destinations and inspire you to enjoy the many and highlighted routes identified on the map. -

Let'slearnaboutwater!

Also, check out these exciting websites SPONSORED BY: If you want to learn more for more water wisdom: about water and what you can do to help keep it clean, n Abou Academy of Natural Sciences ear t W or how you can contact your local www.acnatsci.org L at watershed group, please contact t's e the following organizations: Center for Watershed Protection e r! www.cwp.org L Delaware Audubon Society Vol. 1 No.1 www.DelawareAudubon.org Delaware Chapter of The Nature Conservancy Bathe your brain http://nature.org/states/delaware/ with the facts! Delaware Chapter of the Sierra Club www.delaware.sierraclub.org/ Quench your thirst Delaware Department of Transportation Delaware Department of Natural Resources & Environmental Control P.O. Box 778 www.dnrec.state.de.us for knowledge! Dover, DE 19903 (In-state) 1-800-652-5600 Delaware Nature Society www.delawarenaturesociety.org (Local or Out-of-state) (302) 760-2080 Email: [email protected] Delaware Riverkeeper Network Website: www.deldot.net www.delawareriverkeeper.org Stroud Water Research Center Partnership for the Delaware Estuary www.stroudcenter.org 400 West 9th Street, Suite 100 University of Delaware Wilmington, DE 19801 http://ag.udel.edu/extension/information/nps/nps_home.html 302-655-4990 1-800-445-4935 U. S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Office of Water Fax 302-655-4991 www.epa.gov/ow/ Email: [email protected] U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Watershed Website Website: www.DelawareEstuary.org www.epa.gov/watershed/ Designed and Illustrated by Frank McShane U. S. Fish & Wildlife Service Printed on Recycled Paper www.fws.gov/ ONE WAY Pour paint thinner Wise Water Use is Important! down the drain. -

Table of Contents TOWN, COUNTY, and STATE OFFICIALS

The Town of Bellefonte Comprehensive Plan 2019 Table of Contents TOWN, COUNTY, AND STATE OFFICIALS ............................................................................................................ 5 Town of Bellefonte ..................................................................................................................... 5 New Castle County ..................................................................................................................... 5 State of Delaware ........................................................................................................................ 5 Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................................... 7 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................................... 8 The Authority to Plan .................................................................................................................................................... 9 Community Profile ...................................................................................................................................................... 10 Overview ................................................................................................................................... 10 Location ................................................................................................................................... -

Fy2018tipncc.Pdf

NEW CASTLE COUNTY Adopted March 9, 2017 FY 2018-2021 TRANSPORTATION IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM BR 32 ON FOULK ROAD OVER S. BRANCH NAAMANS CREEK SCOPE/DESCRIPTION: This project involves the replacement of the existing prestressed concrete beams with new prestressed concrete box beams. Additional work includes rehabilitation of the existing abutments, minor reconstruction of the approach roadway, and placement of riprap in the stream to prevent scour. The work will be performed in phases while maintaining traffic on Foulk Road. JUSTIFICATION: The existing concrete deck slab is showing signs of deterioration including cracks and large spalls with exposed corroded steel reinforcement on the bottom side. The bridge is structurally deficient and was selected by the Pontis Bridge Management System for work. The bridge ranks 68th on the DelDOT 2011 Bridge Deficiency List. County: New Castle Investment Area: Core Municipality: Funding Program: Road System – Bridge Improvements Functional Category: Preservation Year Initiated: FY 2013 Project Title Current FY 2017 FY18 FY18 FY18 FY19 FY19 FY19 FY20 FY20 FY20 FY21 FY21 FY21 FY 2018 ‐ FY 22‐23 Phase (All $ x 1000) Estimate TOTAL State Fed Other State Fed Other State Fed Other State Fed Other 2021 TOTAL TOTAL BR 1‐032 on N203 Foulk PE 32.3 ‐ ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ ‐‐ Road over South Branch ROW 25.0 ‐ ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ ‐‐ Naamans Creek CE 124.0 80.0 ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ ‐‐ C 1,303.6 717.6 ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ ‐‐ Utilities 8.9 8.9 ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ ‐‐ Contingency 65.2 52.4 ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ ‐‐ Total 1,559.0 858.9 ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ ‐‐ NEW CASTLE COUNTY – SYSTEM PRESERVATION 2-1 Adopted March 9, 2017 FY 2018-2021 TRANSPORTATION IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM BR 111 ON N235 BENGE ROAD OVER RED CLAY CREEK SCOPE/DESCRIPTION: The rehabilitation work of Bridge 111 includes replacing the existing concrete deck with a new concrete deck and barriers, minor repairs of the substructure, and minor approach roadway work. -

III. Background Research A. Physical Environment the Weldin Plantation

III. Background Research A. Physical Environment The Weldin Plantation Site (7NC-B-11) is located in Brandywine Hundred, New Castle County, Delaware. It is situated in the rolling uplands associated with the Piedmont Upland Section of the Piedmont Physiographic Province at about 360 feet above mean sea level. The Piedmont Upland Section is characterized by broad rolling hills and is dissected by valleys (Plank and Schenck 1998). The Weldin Plantation Site is drained by Matson Run, which is a tributary to Brandywine Creek, which drains into the Delaware River. 1. Climate New Castle County has a humid continental climate that is altered by the nearby Atlantic Ocean. Generally weather systems move from west to east in the warmer half of the year, but during the colder half, alternating high and low pressure systems dominate the weather. Winds from the west and northwest are associated with high pressure systems, and bring cooler temperatures and clear skies. Easterly winds caused by low pressure systems are affected by the Atlantic, providing higher temperatures, clouds, and much of the precipitation to the county (Mathews and Lavoie 1970). The average annual temperature in New Castle County is 54 degrees Fahrenheit, with an average daily temperature of 33 degrees in January (the coldest month) and 76 degrees in July (the warmest month). The County averages about 45 inches of annual precipitation, which is fairly evenly distributed throughout the year. In Wilmington, the growing season lasts from the middle of April to the end of October, but this varies in other parts of the county. In the western and northwestern parts it is 175 to 185 days, while it is 195 to 205 days in the eastern and southeastern parts of the county. -

Sign Unveiling Will Commemorate Long Journey to Road's Naming

Compliments of Bob Weiner, your County Councilman “Making County Government Work for Us” Council District 2, New Castle County, DE [email protected] [email protected] Louis Hinkle, aide to Councilman Weiner: 302-395-8362 Attention civic leaders: You may want to share this electronic newsletter with your neighbors! Councilman Bob Weiner will be singing and dancing to help raise money for the Delaware March of Dimes. The show is called "Dancing for Babies". This is Delaware’s own version of “Dancing With the Stars”. You are invited this Monday April 11 to the Christiana Hilton Ballroom; the show starts promptly at 7 PM. Your $10 admission supports this worthy cause; and can be purchased at the door or on the March of Dimes website. Councilman Bob will open the show singing with the Kishka a cappella Quartet. You can also visit the March of Dimes Delaware Chapter on Facebook. Admission also includes a dance concert, with live music by “Club Phred”, after the 11 local celebrities finish their dance routines. ________________________________________________________________________ Sign unveiling will commemorate long journey to road's naming The entrance to Talley Day Park and the Brandywine Hundred Library was named J. Harlan Day Drive in honor of the man who sold the county 20 acres for the park complex in 1975. The dedication will take place Sunday. New Castle County has set 2:30 p.m. Sunday April 10, 2011 for a ceremonial sign unveiling in a long-awaited road dedication. County Executive Paul G. Clark made the previously nameless road's new moniker official in January, designating the entrance to Talley Day Park and Brandywine Hundred Library as J. -

The History of the Original Forwood School

History of Forwood / History of Forwood School Page 1 of 3 The History of the Original Forwood School 1799 Remember that plaque above the vestibule of Forwood School located on Silverside Road, and how you sometimes wondered about all the boys and girls who had played in the schoolyard below it over more than a hundred years, when that seemed forever, and you wondered too about the grownups that planned and built the school? For lots of us they were our own actual family, for some of us back to twice-great grandparents. For all of us they somehow tied us into exciting times before we were born. Forwood School was to have an active life of 140 years, longer than any other public school building in Delaware has yet had. It"s a story that goes back to the very beginnings of real public education not only in this State but in the country. The late 1700"s were years bubbling with new ideas in government, business, and general ways of living. In 1789 the Constitution of the United States had made a workable single country from the thirteen loosely allied States that had won the Revolution a few years before. Delaware was the first to join that union. Delaware also drafted a new Constitution for itself in 1791/1792. One of its new ideas was an order to the Assembly to provide for education. This was one of the earliest State Constitutions to do so. There had, of course, been schools in Delaware back to Swedish times. Here, as elsewhere, schools had been of three kinds only : private ventures; church supported; and cooperatives where groups of neighbors hired a teacher for their own children. -

848 Act 1982-235 LAWS of PENNSYLVANIA No. 1982-235 AN

848 Act 1982-235 LAWS OF PENNSYLVANIA No. 1982-235 AN ACT SB 831 Providing for the adoption of capital projects related to the repair, rehabilitation or replacement of highway bridges to be financed from current revenue or by the incurring of debt and capital projects related to highway and safety improvement projects to be financed from current revenue of the Motor License Fund. The General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania hereby enacts as follows: Section 1. Short title. This act shall be known and may be cited as the “Highway-Railroad and Highway Bridge Capital BudgetAct for 1982-1983.” Section 2. Total authorization for bridge projects. (a) The total authorization for the costs of the projects itemized pur- suant to section 3 and to be financed from current revenue or by the incurring of debt shall be $979,196,000. (b) The authorization for capital projects inthe category of Highway Projects to beconstructed by the Department of Transportation, its suc- cessors or assigns, and to be financed by the incurring of debt or from the Highway-Railroad and Highway Bridge Improvement Restricted Account within the Motor License Fund, itemized in section 3 under the category of State bridges, is $747,800,000. (c) The authorization for non-State highway bridge projects to be constructed by local government municipalities and to be financed in part with grants not exceeding 80% of the non-Federal share of the costs made to the local government municipalities by the Department of Transportation from revenues deposited in the Highway Bridge Improvement Restricted Account within the Motor License Fund, itemized in section 3 under the category of local bridges, is $231,396,000. -

State of Delaware Surface Water Quality Standards

Presented below are water quality standards that are in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. EPA is posting these standards as a convenience to users and has made a reasonable effort to assure their accuracy. Additionally, EPA has made a reasonable effort to identify parts of the standards that are not approved, disapproved, or are otherwise not in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. TITLE 7 NATURAL RESOURCES & ENVIRONMENTAL CONTROL 1 DELAWARE ADMINISTRATIVE CODE DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES AND ENVIRONMENTAL CONTROL DIVISION OF WATERSHED STEWARDSHIP 7401 Surface Water Quality Standards 1.0 Intent 1.1 It is the policy of the Department to maintain within its jurisdiction surface waters of the State of satisfactory quality consistent with public health and public recreation purposes, the propagation and protection of fish and aquatic life, and other beneficial uses of the water. 1.2 Where conflicts develop between stated surface water uses, stream criteria, or discharge criteria, designated uses for each segment shall be paramount in determining the required stream criteria, which, in turn, shall be the basis of specific discharge limits or other necessary controls. 1.3 Where existing facilities operating under a permit from this Department are required to reduce pollution concentrations or loadings due to the implementation of these surface water quality standards, a reasonable schedule for compliance may be granted in accordance with standards or requirements established in applicable statutes and regulations. 1.4 The Department intends to develop an agency-wide program to assess, manage, and communicate human health cancer risks from the major categories of environmental pollution under its jurisdiction.