The Baton Rouge Community Service Work Program Volume II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tigers in the Draft

Tigers in the Draft NO. NAME, POSITION ROUND TEAM 1949 AAFC 1961 AFL INTRO 1936 21 Albin (Rip) Collins, B 3 Cleveland Bo Strange, C 3 Denver Abe Mickal, B 6 Detroit THIS IS LSU 1950 1962 NFL TIGERS 1937 Al Hover, G 14 Chi. Bears Wendell Harris, B 1 Baltimore Marvin (Moose) Stewart, C 2 Chi. Bears Zollie Toth, B 4 NY Bulldogs Fred Miller, T 7 Baltimore COACHES Gaynell (Gus) Tinsley, E 2 Chi. Cardinals Melvin Lyle, E 10 NY Bulldogs Tommy Neck, B 18 Chicago REVIEW Ebert Van Buren, B 8 NY Giants Earl Gros, B 1 Green Bay 1939 Ray Collins, T 3 San Francisco Jimmy Field, B 16 Green Bay HISTORY Eddie Gatto, T 5 Cleveland Roy Winston, G 4 Minnesota LSU Dick Gormley, C 20 Philadelphia 1951 Billy Joe Booth, T 13 New York Kenny Konz, B 1 Cleveland 1940 Jim Shoaf, G 10 Detroit 1962 AFL Ken Kavanaugh Sr., E 2 Chi. Bears Albin (Rip) Collins, B 2 Green Bay Tommy Neck, HB 20 Boston Young Bussey, B 18 Chi. Bears Joe Reid, C 13 LA Rams Jimmy Field, QB 26 Boston Billy Baggett, B 22 LA Rams Earl Gros, FB 2 Houston 1941 Ebert Van Buren, B 1 Philadelphia Bob Richards, T 32 Oakland Leo Barnes, T 20 Cleveland Y.A. Tittle, QB 1 San Francisco Roy Winston, G 6 San Diego J.W. Goree, G 12 Pittsburgh Wendell Harris, HB 7 San Diego 1952 1943 Jim Roshto, B 12 Detroit 1963 NFL Bill Edwards, G 29 Chi. Cardinals George Tarasovic, C 2 Pittsburgh Dennis Gaubatz, LB 8 Detroit Willie Miller, G 30 Cleveland Rudy Yeater, T 13 San Francisco Buddy Soefker, B 18 Los Angeles Percy Holland, G 22 Detroit Jess Yates, E 20 San Francisco Gene Sykes, B 8 Philadelphia Walt Gorinski, B 17 Philadelphia Chet Freeman, B 23 Texas Jerry Stovall, B 1 St. -

The Failure of Louisiana Campaign Finance Law: a Case Study of Brnext and the 2004 Baton Rouge Mayoral Election

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2007 The aiF lure of Louisiana Campaign Finance Law: A Case Study of BRNext and the 2004 Mayoral Election Casey Elizabeth Rayborn Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Rayborn, Casey Elizabeth, "The aiF lure of Louisiana Campaign Finance Law: A Case Study of BRNext and the 2004 Mayoral Election" (2007). LSU Master's Theses. 1357. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/1357 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FAILURE OF LOUISIANA CAMPAIGN FINANCE LAW: A CASE STUDY OF BRNEXT AND THE 2004 BATON ROUGE MAYORAL ELECTION A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Mass Communication in The Manship School of Mass Communication by Casey Elizabeth Rayborn B.A., Louisiana State University, May 2003 August 2007 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I want to thank God for blessing me in so many ways and for being my foundation I can stand firm on. I would like to thank my chair Dr. Emily Erickson for her guidance, support, and enthusiasm throughout this project, and my committee members Dr. -

All-Americans

All-Americans INTRO A F L S THIS IS LSU Nacho Albergamo ..........................center (1987) Alan Faneca....................offensive guard (1997) Tyler LaFauci ....................................guard (1973) Lance Smith ................offensive tackle (1984) TIGERS Charles Alexander ............tailback (1977, 1978) Kevin Faulk ............................all-purpose (1996) David LaFleur ............................tight end (1996) Marcus Spears............defensive tackle (2004) Mike Anderson ........................linebacker (1970) Sid Fournet ......................................tackle (1954) Chad Lavalais..............defensive tackle (2003) Marvin “Moose” Stewart ..center, 1935 (1936) COACHES Max Fugler........................................center (1958) Jerry Stovall ..............................halfback (1962) REVIEW B M George Bevan..........................linebacker (1969) G Todd McClure ..................................center (1998) T HISTORY James Britt ............................cornerback (1982) John Garlington ..................................end (1967) Anthony McFarland ..............noseguard (1998) George Tarasovic ..........................center (1951) LSU Michael Brooks........................linebacker (1985) Skyler Green......return specialist (2003) Eric Martin ..................................split end (1983) Jimmy Taylor ..............................fullback (1957) Fred Miller ........................................tackle (1962) Gaynell “Gus” Tinsley ............end (1935, 1936) C J Doug Moreau -

LSU Vs. Notre Dame History

LSU vs. Notre Dame History INTRO NOTEBOOK COACHES TIGERS REVIEW THE SEASON LSU and Notre Dame renew its storied rivalry HISTORY on Jan. 3 when the teams meet in the Allstate Sugar Bowl at the Louisiana Superdome in New Orleans. The contest will mark the 10th meeting between the teams, but the first since a 39-36 Notre Dame win in South Bend in 1998. Of the nine previous games between the teams, four have been decided by three points or less. At least one team has been ranked for all nine meetings between the Dalton Hilliard (21) runs against the Irish defense in 1985. schools and this year's Sugar Bowl contest will represent the first time since 1971 that both teams go into the contest ranked. LSU is ranked No. 4, while Notre Dame is No. 11. The Beginning The LSU-Notre Dame series started back in 1970 when the Irish squeaked out a 3-0 win over the Tigers. The Notre Dame win prompted a Chicago Tribune writer to pen, "If Notre Dame is number one, LSU has got to be one-A." And thus, the rivalry in a rarely played series of games was born. The Series: Notre Dame leads 5-4 LSU and Notre Dame play for the 10th time when the teams meet on Jan. 3 in the Allstate Sugar Bowl in New Orleans … Notre Dame leads the series 5-4 … The series dates back to 1970 when the fourth-ranked Irish posted a 3-0 win over sixth-ranked LSU in South Kevin Faulk had 26 carries for 105 in the first of two matchup during the 1997 season. -

2007 Season Notebook LSU

2007 Season Notebook LSU INTRO NOTEBOOK COACHES TIGERS REVIEW THE SEASON HISTORY LSU vs. Ohio State BCS National Championship Game Jan. 7, 2008 • 7 p.m. CST • FOX New Orleans, La. • Louisiana Superdome LSU To Face Ohio State concerned, LSU has played in two of college For BCS National Title football’s five most watched games in 2007. LSU vs. No. 1 Ranked Teams LSU will try to become the first team in the LSU’s win over Tennessee in the SEC LSU’s game against Ohio State will mark only the ninth time that LSU has faced an opponent nation to collect a second BCS National Championship Game drew a 5.9 rating, the ranked No. 1 in the nation in the Associated Press Poll. LSU is 1-7-1 all-time against No. 1-ranked Championship when the Tigers face Ohio State in highest rating for that contest since the Tigers teams. LSU’s only win against a top-ranked team came in 1997 when the Tigers beat Florida, 28- the title game on Monday, Jan. 7 at the beat the Vols in prime time in 2001. In addition, 21, in Tiger Stadium. That’s the last time LSU has faced a No. 1-ranked team. The following is a Louisiana Superdome in New Orleans. Since the LSU’s win over Florida on Oct. 6 drew a 5.3 look at LSU’s results against No. 1 teams: inception of the BCS National Championship rating. The most watched game in 2007 was the Game in 1998, nine different teams have claimed Oklahoma-Missouri primetime contest on Dec. -

19FB Gamenotes15nationalch

2019 Postseason Awards Joe Burrow • QB Kristian Fulton • CB Heisman Trophy AP Second Team All-SEC Maxwell Award Second Team PFF All-America Manning Award Finalist Walter Camp Player of the Year Davey O’Brien Award Justin Jefferson • WR AP Second Team All-SEC Johnny Unitas Golden Arm Award Winner AP Player of the Year The Athletic’s CFB Person of the Year Rashard Lawrence • DL AP First Team All-SEC* Second Team All-SEC Coaches’ Team AP SEC Offensive Player of the Year* First Team All-SEC Coaches’ Team Damien Lewis • OL Unanimous First Team All-American AP Second Team All-SEC First Team ESPN All-America Second Team All-SEC Coaches’ Team First Team Sporting News All-America First Team Athletic All-America First Team FWAA All-America First Team AP All-America First Team AFCA All-America Adrian Magee • OL First Team PFF All-America Second Team All-SEC Coaches’ Team First Team Walter Camp All-America First Team Athletic All-America JaCoby Stevens • S/LB First Team CBS All-America Second Team All-SEC Coaches’ Team First Team Sports Illustrated All-America First Team USA Today All-America Derek Stingley Jr. • CB AP First Team All-SEC Ja’Marr Chase • WR AP SEC Newcomer of the Year Biletnikoff Award Second Team All-SEC Coaches’ Team AP First Team All-SEC* SEC All-Freshman Team First Team All-SEC Coaches’ Team Consensus First Team All-America Unanimous First-Team All-America First Team Sporting News All-America First Team ESPN All-America First Team AP All-America First Team Sporting News All-America First Team ESPN All-America First Team AP All-America -

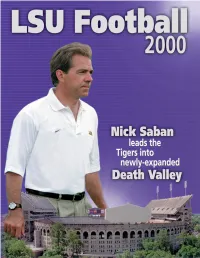

2000 Lsu Football Signees Name Pos Ht Wt Cl

2 0 0 0 L S U F O O T B A L L S C H E D U L E Sept. 2 WESTERN CAROLINA Baton Rouge 7 p.m. Sept. 9 HOUSTON Baton Rouge 7 p.m. Tigers Sept. 16 *at Auburn Auburn, Ala. 6 p.m. Sept. 23 ALA.-BIRMINGHAM Baton Rouge 7 p.m. Sept. 30 *TENNESSEE Baton Rouge 7 p.m. Oct. 7 *at Florida Gainesville, Fla. 12 noon Oct. 14 *KENTUCKY Baton Rouge 7 p.m. Coaches Oct. 21 *MISSISSIPPI STATE Baton Rouge 7 p.m. Nov. 4 *ALABAMA Baton Rouge 7 p.m. Nov. 11 *at Ole Miss Oxford, Miss. 1 p.m. Nov. 24 *at Arkansas Little Rock, Ark. 1:30 p.m. Preview Homecoming: Sept. 23 vs. Alabama-Birmingham All times CENTRAL and subject to change * Denotes Southeastern Conference games Review Records History Honors LSU Media Quick Facts LSU Football Coaching Staff NAME POSITION ALMA MATER YEAR AT LSU Nick Saban Head Coach Kent State '73 First Derek Dooley Tight Ends/Recruiting Coordinator Virginia '91 First Phil Elmassian Defensive Coordinator William & Mary '74 First Jimbo Fisher Offensive Coordinator/Quarterbacks Salem College '89 First Michael Haywood Running Backs Notre Dame '86 Sixth Stan Hixon Associate Head Coach/Wide Receivers Iowa State '79 First Pete Jenkins Defensive Line Western Carolina '64 12th Sal Sunseri Linebackers/Special Teams Pittsburgh '82 First Rick Trickett Assistant Head Coach/Offensive Line Glenville State '72 First Mel Tucker Defensive Backs Wisconsin '95 First Sam Nader Administrative Assistant Auburn '67 26th L S U A T H L E T I C D E P A R T M E N T Mailing Address Street Address Fax P.O. -

Cvive La TI;Ffe(En~E'

CVive la TI;ffe(en~e' SIXTH SOUTHEASTERN CONFERENCE of LESBIANS AND GAY ~N APRIL 10-12. 1981 - "::,""" .. :~ .... , -. > .,:...~.I.c.;. Hosted by the LSU Students for Gay Awareness -2- -3- The LSU Students for Gay Awareness was recognized as an official student group on -April 25, 1977. Many members of the administration thought it would die after a few semesters. They were wrong. As the oldest gay student group in the Office of the Mayor-President state, the LSU SfGA is a growing and integral part of the LSU student body. PAT SCREEN Meetings are held in the Union twice a month with an average attendance at 25. Mayor-President Cit , of Baton Rouge Parish of East Baton Rouge The SfGA's newsletter, "Ie papillon," is published monthly during spring and fall semesters. Speakers on health problems, relationships, personal communication, ~2~ SI. Louis Street gay art and literature, and discussions on coming out and combatting homophobia Batou Rouge. Louisiana are just a few of the meetings topics. Thanksgiving food drives and Christmas toy 70ROI drives have been held with success the past two years. The 1981 Lavender Ball, the 504/389-3100 SfGA's anniversary party, will be two weeks after the conference. If Conference '81 11arch 13, 1981 is a success, and we believe it will be, members will indeed have a reason for celebration. Dear Conference Participants: While in our city, I hope you will have time to discover some of the many reasons why Baton Rouge is among the most progressive and dynamic communities in the nation. -

Teams of the Century

H O N O R S Teams of the Century MODERN DAYS TEAM of the CENTURY OFFENSE WR . .Wendell Davis 1984-87 WR . .Eric Martin 1981-84 OL . .Nacho Albergamo 1984-87 OL . .Eric Andolsek 1984-87 OL . .Tyler Lafauci 1971-73 OL . .Lance Smith 1981-84 OL . .Charles “Bo”Strange 1958-60 QB . .Bert Jones 1970-72 RB . .Charles Alexander 1975-78 RB . .Billy Cannon 1957-59 RB . .Dalton Hilliard 1982-85 RB . .Jimmy Taylor 1956-57 PK . .David Browndyke 1986-89 LSU cadets at football practice in the fall of 1894. DEFENSE DL . .A.J. Duhe 1973-76 s part of the commemoration of the was selected through a state wide balloting of DL . .Ronnie Estay 1969-71 first 100 years of LSU football in 1993, fa n s . The ballots were distributed by direc t DL . .Fred Miller 1960-62 tw o teams were selected to rep re s e n t mail and through newspapers across the state. DL . .Henry Thomas 1983-86 A the greatest players in the history An y LSU player from 1937 to 1992 LB . .Mike Anderson 1968-70 of the Tiger gridiron . who earned Al l - A m e r i c a , first or LB . .Micheal Brooks 1983-86 The Early Years Team of the second team Al l - S E C , LSU Sports LB . .Warren Capone 1971-73 Ce n t u r y rep r esents the best play- Hall of Fame or Louisiana Sports LB . .Roy“Moonie”Winston 1959-61 ers from 1893, the first year of Hall of Fame honors was named DB . -

2C6d5b4f-02Fb197-217.Pdf

T I G E R S C O A C H E S P R E V I E W R E V I E W R E C O R D S H O N O R S H I S T O R Y L S U M E D I A Individual Records MOST YARDS GAINED PER GAME SEASON: 279.2 Rohan Davey, 2001 (3,351 in 12 games) 236.7 Tommy Hodson,1989 (2,604 in 11 games) 221.5 Jeff Wickersham,1983 (2,436 in 11 games) 220.0 Herb Tyler, 1998 (2,200 in 10 games) 212.2 Josh Booty, 2000 (2,121 in 10 games) 201.8 Tommy Hodson,1986 (2,219 in 11 games) 200.0 Jamie Howard,1995 (1,400 in 7 games) CAREER: 203.1 Tommy Hodson,1986-89 (8,938 in 44 games) 184.8 Herb Tyler, 1995-98 (6,654 in 36 games) 197.5 Josh Booty, 1999-2000 (3,951 in 20 games) 179.7 Rohan Davey, 1998-2001 (4,492 in 25 games) 176.4 Jeff Wickersham,1982-85 (6,705 in 38 games) 155.4 Alan Risher, 1980-82 (5,127 in 33 games) 154.4 Jamie Howard,1992-95 (5,560 in 36 games) 121.5 Nelson Stokley, 1965-67 (2,308 in 19 games) MOST YARDS GAINED PER PLAY GAME: (min.20 plays) 15.4 Jamie Howard vs.Rice,9-23-95 (356 yards on 23 plays) 11.4 Rohan Davey vs.Alabama,11-3-01 (540 yards on 47 plays) 11.7 Kevin Faulk vs.Houston,9-7-96 (246 yards on 21 plays) 10.9 Bert Jones vs.Auburn, 10-14-72 (240 yards on 22 plays) SEASON: (min.800 yards) 8.3 Rohan Davey, 2001 (3,351 yards on 405 plays) 7.6 Nelson Stokley, 1965 (917 yards on 121 plays) Tommy Hodson (min.300 plays) 7.0 Tommy Hodson,1989 (2,604 yards on 373 plays) Total Offense CAREER: (min.900 plays) 6.8 Tommy Hodson,1986-89 (8,938 yards on 1,307 plays) MOST PLAYS 6.6 Herb Tyler, 1995-98 (6,654 on 1,006 plays) GAME: 61 Josh Booty vs.Auburn,9-18-99 (3 rush, 58 pass) 5.7 Jeff Wickersham,1982-85 (6,705 yards on 1,181 plays) 55 Tommy Hodson vs. -

Florida Baton Rouge, La

@LSUFootball NATIONAL CHAMPIONS 1958 • 2003 • 2007 SEC CHAMPIONS 2019 FOOTBALL 1935 • 1936 • 1958 • 1961 1970 • 1986 • 1988 • 2001 GAME NOTES • 2003 • 2007 • 2011 GAME Tiger Stadium vs Florida Baton Rouge, La. 6 October 12, 2019 7 p.m. CT • ESPN BREAKDOWN 2019 SCHEDULE DATE OPPONENT/TV TIME (CT) SERIES RECORD LSU Aug. 31 Georgia Southern [SECN] Won, 55-3 LSU leads 1-0 Record 5-0, 1-0 SEC Sept. 7 at No. 9 Texas [ABC] Won, 45-38 Texas leads 9-8-1 Ranking No. 5 AP/6 Coaches Sept. 14 Northwestern State (Purple Game) [SECN] Won, 65-14 LSU leads 12-0 Last Game October 5 vs. Utah State Sept. 21 at Vanderbilt * [SECN] Won, 66-38 LSU leads 23-7-1 Won, 42-7 Oct. 5 Utah State [SECN] Won, 42-6 LSU leads 3-0 Head Coach Ed Orgeron (3rd Season) Oct. 12 Florida * (Homecoming) [ESPN] 7 p.m. Florida leads 33-29-3 Career Record 46-36 Oct. 19 at Mississippi State * TBA LSU leads 74-35-3 LSU Record 30-9 Oct. 26 Auburn * (Gold Game) TBA LSU leads 30-22-1 vs. Florida 1-2 Nov. 9 at Alabama * TBA Alabama leads 53-25-5 LSU vs. Florida 29-33-3 Nov. 16 at Ole Miss * TBA LSU leads 62-41-4 Nov. 23 Arkansas * (LSU Salutes) TBA LSU leads 40-22-2 Florida Nov. 30 Texas A&M * (Senior Tribute) TBA LSU leads 33-20-3 Record 6-0, 3-0 SEC Dec. 7 SEC Championship [CBS] 2:30 p.m. LSU 4-1 in Title Game Ranking No. -

National Awards

National Awards National Coach of the Year (Selected by the Walter Camp Football Foundation) 1982 - Jerry Stovall All-America Strength Team (Selected by the National Strength Coaches Association) 1986 - Eric Andolsek, OG 1989 - Victor Jones,FB 1997 - Chuck Wiley, DT 1997 - Anthony McFarland,DT 1999 - Louis Williams, OT National Football Foundation & Hall of Fame (Located in Southbend, Ind. Year indicated is when individual was inducted, and years in parentheses are those in which individual lettered or was a coach at LSU.) PLAYERS 1956 - Gaynell Tinsley, E (lettered 1934-35-36, was head coach 1948 to 1954) 1963 - Ken Kavanaugh, Sr., E (1937-38-39) Billy Cannon was the winner of the Heisman and 1967 - Abe Mickal, HB (1933-34-35) Walter Camp Memorial Trophies in 1959. 1971 - G.E.“Doc”Fenton, QB (1907-08-09) Heisman Memorial Trophy 1995 - Tommy Casanova, S (1969-70-71) (Presented annually by the Downtown Athletic Club of New York City, to the most out - standing player in college football.) COACHES 1959 - Billy Cannon, HB 1951 - Dana X. Bible (head coach, 1916) Mike Donahue (head coach, 1923 to 1927) National Collegiate Player of the Year 1954 - Lawrence M.“Biff” Jones (head coach,1932 to 1934) (Selected by the Cleveland Touchdown Club) Bernie H. Moore (head coach, 1935 to 1947) 1972 - Bert Jones, QB 1986 - Charles McClendon (head coach, 1962 to 1979) Walter Camp Memorial Trophy Television Awards (Presented annually by the Touchdown Club of Washington, D.C., to the collegiate back of ABC-TV/Chevrolet Lineman of the Year the year. Walter Camp was the father of American football.) 1971 - Ronnie Estay, DT 1959 - Billy Cannon, HB 1962 - Jerry Stovall, HB All-Star Bowl Game Awards East-West Shrine Game Most Valuable Player Biletnikoff Award 1985 - Garry James,TB (offense) (Presented annually by the Touchdown Club of Tallahassee, Fla., to the collegiate wide receiver of the year.) 2001 - Josh Reed,WR Senior Bowl Most Valuable Player 1958 - Jim Taylor, FB Knute Rockne Memorial Trophy 1976 - A.J.