Medievalisms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sunday Morning Grid 3/25/12

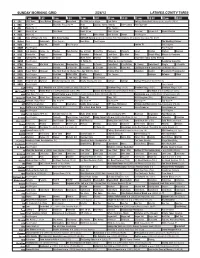

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 3/25/12 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning Å Face/Nation Doodlebops Doodlebops College Basket. 2012 NCAA Basketball Tournament 4 NBC News Å Meet the Press (N) Å Conference Wall Street Golf Digest Special Golf Central PGA Tour Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) IndyCar Racing Honda Grand Prix of St. Petersburg. (N) XTERRA World Champ. 9 KCAL News (N) Prince Mike Webb Joel Osteen Shook Best Deals Paid Program 11 FOX D. Jeremiah Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program NASCAR Racing 13 MyNet Paid Tomorrow’s Paid Program Best Buys Paid Program Doubt ››› (2008) 18 KSCI Paid Hope Hr. Church Paid Program Iranian TV Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Sid Science Quest Thomas Bob Builder Joy of Paint Joseph Campbell and the Power of Myth Death, sacrifice and rebirth. Å 28 KCET Hands On Raggs Busytown Peep Pancakes Pufnstuf Land/Lost Hey Kids Taste Simply Ming Moyers & Company 30 ION Turning Pnt. Discovery In Touch Mark Jeske Beyond Paid Program Inspiration Today Camp Meeting 34 KMEX Paid Program Noticias Univision Santa Misa Desde Guanajuato, México. República Deportiva 40 KTBN Rhema Win Walk Miracle-You Redemption Love In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley From Heart King Is J. Franklin 46 KFTR Misión S.O.S. Toonturama Presenta Karate Kid ›› (1984, Drama) Ralph Macchio. -

Friday Evening, April 13, 2012

THE COURIER-JOURNAL | SUNDAY,APRIL 8, 2012 | V25 FRIDAY EVENING, APRIL 13, 2012 (N) New Broadcast INS:Insight ATT:AT&T DSH:Dish DIR:DirecTV MOVIES SPORTS KIDS INS ATT DSH DIR 3PM3:30 4PM4:30 5PM5:30 6PM6:30 7PM7:30 8PM8:30 9PM9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 ANPL 60 252 184 282 Cutest Dog Infested! Hillbilly Handfishin’ River Monsters Alaska Wildlife North Woods Law North Woods Law (N) Rattlesnake Republic North Woods Law DISC American Chopper Cus- American Chopper Cus- MythBusters Urban MythBusters Urban MythBusters Urban MythBusters Urban Deadliest Catch “The Deadliest Catch “Deck- Deadliest Catch “The 38 120 182 278 tom motorcycles. tom motorcycles. myths tested. myths tested. myths tested. myths tested. Gamble” Difficult choice. hands” Heart; muscle. Gamble” Difficult choice. DISN Good Luck Good Luck Good Luck Good Luck Jessie Jessie Shake It Good Luck Shake It Jessie Jessie (N) A.N.T. Farm Phineas and Good Luck Austin & Good Luck Jessie Jessie 29 302 172 290 Charlie Charlie Charlie Charlie Up! Charlie Up! (N) Ferb Charlie Ally Charlie (TV G) (N) FAM "" The ""! AWalk to Remember (‘02) Shane West, Mandy Moore. A ""! The Princess Diaries (‘01) Anne Hathaway, Julie Andrews. "" The Princess Diaries 2:Royal Engagement (‘04) Anne The 700 Club 40 178 180 311 Prince (‘04) cruel boy romances a kind girl. (PG) Young girl learns she isaprincess. (G) Hathaway, Heather Matarazzo. Princess’ suitors. (G) FOOD 46 452 110 231 Giada Giada Contessa Contessa Paula’s Paula’s Diners Diners Best Thing Best Thing Diners Diners Diners Diners Diners Diners Diners Diners HGTV 51 450 112 229 Cousins Cousins Income Income Prop Bro Prop Bro Hunters Hunters Hunters Hunters House Hunters Green Home 2012 (N) Hunters Hunters Hotel Impossible FAMILY HIST 54 256 120 269 MonsterQuest Modern Marvels Modern Marvels Modern Marvels Modern Marvels American Pickers Full Metal Jousting Full Metal Jousting Full Metal Jousting HUB MIB “Under- Batman Be- Hero Squad G.I. -

1-2 Front CFP 2-15-12.Indd

Page 2 Colby Free Press Wednesday, February 15, 2012 Area/State Weather Police chase purse thief Briefly From “POLICE,” Page 1 Mission Ridge, he said, and the The number at headquarters is Musical group to appear at Mingo Church checkbook from the 400 block 460-4460. The accoustic group the Josties will give a free concert at 7 p.m. Thurs- Mission Ridge, Jones said. of South School. People could help prevent day at the Mingo Bible Church. Based in Milk River, Alberta, Canada, the “More than likely, he got be- As of midmorning, the check- thefts from cars by simply taking Jost family shares God’s faithfulness through testimony and music in a tween two houses and dumped book was still missing, the chief valuables inside, he said, and by blend of styles. For information, call Pastor Tom Peyton at 462-2930. the purse,” Jones said. “He took said. The thief was described locking their cars and taking the the cash and left the cell phone as a white man, about 5 foot, 8 keys out of the ignition. and everything there.” Women can learn to be feminine and godly inches tall, slender and wearing “People should lock their The owner was to come to A program called “Feminine and Fabulous” will be presented at 7 p.m. a light blue jacket and a dark cars,” he said. “They should lock the Law Enforcement Center to Thursday at the College Drive Assembly of God Church. Women who stocking cap. their homes at night or when identify the contents, he said, struggle with the pressures of today’s society about how to dress, talk and “If anybody saw anyone walk- they’re not home. -

May 16, 2012 • Vol

The WEDNESDAY, MAY 16, 2012 • VOL. 23, NO. 2 $1.25 Congratulations to Ice Pool Winner KLONDIKE Mandy Johnson. SUN Breakup Comes Early this Year Joyce Caley and Glenda Bolt hold up the Ice Pool Clock for everyone to see. See story on page 3. Photo by Dan Davidson in this Issue SOVA Graduation 18 Andy Plays the Blues 21 The Happy Wanderer 22 Summer 2012 Year Five had a very close group of The autoharp is just one of Andy Paul Marcotte takes a tumble. students. Cohen's many instruments. Store Hours See & Do in Dawson 2 AYC Coverage 6, 8, 9, 10, 11 DCMF Profile 19 Kids' Corner 26 Uffish Thoughts 4 TV Guide 12-16 Just Al's Opinion 20 Classifieds 27 Problems at Parks 5 RSS Student Awards 17 Highland Games Profiles 24 City of Dawson 28 P2 WEDNESDAY, May 16, 2012 THE KLONDIKE SUN What to The Westminster Hotel Live entertainment in the lounge on Friday and Saturday, 10 p.m. to close. More live entertainment in the Tavern on Fridays from 4:30 SEE AND DO p.m.The toDowntown 8:30 p.m. Hotel LIVE MUSIC: - in DAWSON now: Barnacle Bob is now playing in the Sourdough Saloon ev eryThe Thursday, Eldorado Friday Hotel and Saturday from 4 p.m. to 7 p.m. This free public service helps our readers find their way through the many activities all over town. Any small happening may Food Service Hours: 7 a.m. to 9 p.m., seven days a week. Check out need preparation and planning, so let us know in good time! To our Daily Lunch Specials. -

Sunday Morning Grid 2/26/12 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 2/26/12 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face/Nation Rangers Horseland The Path to Las Vegas Epic Poker College Basketball Pittsburgh at Louisville. (N) Å 4 NBC News Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Laureus Sports Awards Golf Central PGA Tour Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) Å News (N) Å News Å Eye on L.A. Award Preview 9 KCAL News (N) Prince Mike Webb Joel Osteen Shook Paid Program 11 FOX Hour of Power (N) (TVG) Fox News Sunday NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup: Daytona 500. From Daytona International Speedway, Fla. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Tomorrow’s Paid Program Best Buys Paid Program The Wedding Planner 18 KSCI Paid Hope Hr. Church Paid Program Iranian TV Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Sid Science Curios -ity Thomas Bob Builder Joy of Paint Paint This Dewberry Wyland’s Sara’s Kitchen Kitchen Mexican 28 KCET Hands On Raggs Busytown Peep Pancakes Pufnstuf Land/Lost Hey Kids Taste Simply Ming Moyers & Company 30 ION Turning Pnt. Discovery In Touch Mark Jeske Beyond Paid Program Inspiration Today Camp Meeting 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol de la Liga Mexicana República Deportiva 40 KTBN Rhema Win Walk Miracle-You Redemption Love In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley From Heart King Is J. -

The Knight and War: Alternative Displays of Masculinity in El Passo Honroso De Suero De Quiñones, El Victorial, and the Historia De Los Hechos Del Marqués De Cádiz

THE KNIGHT AND WAR: ALTERNATIVE DISPLAYS OF MASCULINITY IN EL PASSO HONROSO DE SUERO DE QUIÑONES, EL VICTORIAL, AND THE HISTORIA DE LOS HECHOS DEL MARQUÉS DE CÁDIZ Grant Gearhart A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Studies (Spanish). Chapel Hill 2015 Approved by: Frank Dominguez Lucia Binotti Carmen Hsu Josefa Lindquist Rosa Perelmuter ©2015 Grant Gearhart ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Grant Gearhart: THE KNIGHT AND WAR: ALTERNATIVE DISPLAYS OF MASCULINITY IN EL PASSO HONROSO DE SUERO DE QUIÑONES, EL VICTORIAL, AND THE HISTORIA DE LOS HECHOS DEL MARQUÉS DE CÁDIZ (Under the direction of Frank A. Domínguez) This study examines the changes in the portrayal of knights in three early modern Spanish texts: El passo honroso de Suero de Quiñones, El Victorial, and the Historia de los hechos del Marqués de Cádiz. These three works are compared to the rather formulaic examples found in Amadís de Gaula, which contains examples of knights portrayed as exemplary warriors, but that are of one-dimensional fighters exercising a mostly outmoded form of warfare. No longer the centerpiece of the battlefield, real fifteenth-century knights were performing military functions that required them to be not only masters of traditional skills like riding, jousting, and sword-fighting, but also to undergo training in the use of weapons previously reserved for foot soldiers, more consistently lead larger units of troops in battle, and study in order to improve their speaking skills. -

Marching for Healthy Babies

WEEKEND EDITION FRIDAY, APRIL 13 & SATURDAY, APRIL 14, 2012 | YOUR COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER SINCE 1874 | 75¢ Lake City Reporter LAKECITYREPORTER.COM Hair- raising efforts Loveloud A Wellborn-based United Way’s alternative rock/group, local impact Loveloud is the final per- formance in this season’s totals $1,075,973. FGC Entertainment series. The group, most recently By TONY BRITT seen on the Warped Tour, [email protected] perform on April 14th at Florida Gateway College. For more information or Few, if any men, want to for tickets, call (386) 754- lose most of their hair at 4340 or visit www.fgcenter- one time. tainment.com. But if losing his hair, in a public meeting, with a Toxic roundup pair of pink hair clippers, in front of close to 100 people The Columbia County meant the United Way of Toxic Roundup will be Suwannee Valley met its Saturday, April 14 at challenge goal, then Mike the Columbia County McKee, United Way presi- Fairgrounds from 9 a.m. dent took the buzz cut as a to 3 p.m. Safely dispose of COURTESY PHOTO good sport. your household hazard- Kaylie Spradley at 8 and a half months old in a photo taken Jan. 12. United Way of Suwannee ous wastes, including old Valley held its 2012 Royal paint, used oil, pesticides Awards Banquet and annual and insecticides. The meeting Thursday night at process is quick, easy Florida Gateway College and free of charge to Howard Conference Center, residents. There is a small Marching for chronicling the organiza- fee for businesses. Help keep our environment HAIR continued on 7A safe! For information call Columbia County landfill Healthy Babies at (386)752-6050. -

Song of the Sparrow by Lisa Ann Sandell

Song of the Sparrow by Lisa Ann Sandell About the Book Feisty and independent Elaine of Ascolat lives with her father and two brothers in the midst of a war camp. Since her mother was murdered when she was a child, Elaine has grown up in the camp, treating all the men there as her brothers, with her only female companion being the mysterious Morgan. Arthur, Elaine’s friend, is named leader of the Britons in the battle against marauding foreigners. Longing for a closer bond with Lancelot, who has treated her with affection since she was a child, Elaine is horrified to see that he is hopelessly in love with Gwynivere, the woman chosen for Arthur to marry. When Arthur’s army marches to fight the Saxons, Elaine and Gwynivere both follow the men in secret and are captured by the enemy. The cunning and courage of the two women helps turn the tide of the battle, and their shared adventure helps Elaine overcome her jealousy and find her own true destiny at last. Discussion Questions Characters 1) How would Elaine’s life have been different if her mother had lived? How much has her personality been shaped by living in the camp? 2) Compare Tirry and Lavain. In what ways are they the same? In what ways are they different? Why do they interact with Elaine in different ways? 3) Compare Lancelot and Tristan. Do they have qualities that are the same? In what ways are they different? 4) Compare Elaine, Morgan, and Gwynivere. In what ways are they the same? What qualities are unique to each of them? 5) How does Arthur assert his leadership of the camp? -

Robert Graves the White Goddess

ROBERT GRAVES THE WHITE GODDESS IN DEDICATION All saints revile her, and all sober men Ruled by the God Apollo's golden mean— In scorn of which I sailed to find her In distant regions likeliest to hold her Whom I desired above all things to know, Sister of the mirage and echo. It was a virtue not to stay, To go my headstrong and heroic way Seeking her out at the volcano's head, Among pack ice, or where the track had faded Beyond the cavern of the seven sleepers: Whose broad high brow was white as any leper's, Whose eyes were blue, with rowan-berry lips, With hair curled honey-coloured to white hips. Green sap of Spring in the young wood a-stir Will celebrate the Mountain Mother, And every song-bird shout awhile for her; But I am gifted, even in November Rawest of seasons, with so huge a sense Of her nakedly worn magnificence I forget cruelty and past betrayal, Careless of where the next bright bolt may fall. FOREWORD am grateful to Philip and Sally Graves, Christopher Hawkes, John Knittel, Valentin Iremonger, Max Mallowan, E. M. Parr, Joshua IPodro, Lynette Roberts, Martin Seymour-Smith, John Heath-Stubbs and numerous correspondents, who have supplied me with source- material for this book: and to Kenneth Gay who has helped me to arrange it. Yet since the first edition appeared in 1946, no expert in ancient Irish or Welsh has offered me the least help in refining my argument, or pointed out any of the errors which are bound to have crept into the text, or even acknowledged my letters. -

08 3-6-12 TV Guide.Indd

Page 8 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, March 6, 2012 Monday Evening March 12, 2012 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC The Bachelor The Bachelor Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live WEEK OF FRIDAY , MARCH 9 THROUGH THURSDAY , MARCH 15 KBSH/CBS How I Met 2 Broke G Two Men Mike Hawaii Five-0 Local Late Show Letterman Late KSNK/NBC The Voice Smash Local Tonight Show w/Leno Late FOX House Alcatraz Local Cable Channels A&E Hoarders Hoarders Intervention Intervention Hoarders AMC Braveheart Braveheart ANIM Gator Boys Finding Bigfoot Rattlesnake Republic Gator Boys Finding Bigfoot CNN Anderson Cooper 360 Piers Morgan Tonight Anderson Cooper 360 E. B. OutFront Piers Morgan Tonight DISC American Chopper American Chopper Sons of Guns American Chopper Sons of Guns DISN Austin Hocus Pocus Austin Phineas Wizards Wizards Wizards E! Fashion Police Khloe Khloe Ice-Coco Ice-Coco Chelsea E! News Chelsea Norton TV ESPN NBA Basketball NBA Basketball ESPN2 Bracketology MLS Soccer SportsCenter FAM Pretty Little Liars Secret-Teen Pretty Little Liars The 700 Club Prince Prince FX Twilight Twilight HGTV Love It or List It House House House Hunters My House First House House HIST Pawn Pawn American Pickers Pawn Pawn American Pickers Pawn Pawn LIFE Untraceable Panic Room Untraceable Listings: MTV Tribute to Dunn Jackass 3.5 Caged Jackass 3.5 NICK Friends Friends Friends Friends Friends Friends Friends Friends Friends Friends SCI Being Human Being Human Lost Girl Being Human Lost Girl For your SPIKE Ways Die Ways Die Ways Die Ways Die Ways Die Ways Die Ways Die Ways Die Ways Die Ways Die TBS Fam. -

Basketball A-10 Tournament Championship NCAA Basketball Big-10 (15) WANE Movies Nation Program Wn Myst

THE HERALD The REPUBLICAN Star THE NEWS SUN March 11 - March 17, 2012 tvweekly tvweeklyT ELEVISION L ISTINGS Nick Eversman stars in "Missing" - Page 2 7UXVWWKH 0LGDV7RXFK $5 OFF ANY OIL CHANGE With coupon only. Cannot be combined with any other offer. Exp. 4-30-12 /RFDOO\RZQHG DQGRSHUDWHG Open: M-F 7:30 - 5; Sat. 7:30 - Noon 2401 N. Wayne St. Angola, IN (260) 665-3465 Buoy, oh buoy. 9LZ[H\YHU[:[`SL+PUPUN+HPS` ,]LUPUN(J[P]P[PLZ9LSPNPV\Z:LY]PJLZ Don Gura, Agent Great boat insurance. 633 N. Main St., Low rates. Kendallville All aboard. The water’s more 347-FARM (3276) fun when you know you’re www.dongura.net covered with the best. Like a good neighbor, 05+,7,5+,5;30-,:;@3,*644<50;@ State Farm is there.® CALL ME TODAY. 4VU[OS`3LHZL`YZHUKVSKLY 4HPU[LUHUJL-YLL )LKYVVT9HUJO7H[PV/VTLZ <[PSP[PLZ0UJS\KLK (TLUP[PLZ0UJS\KL! +HPS`4LHSZPU(ZZPZ[LK3P]PUN >LLRS`/V\ZLRLLWPUN3PULU *OHUNL+PZO;=)HZPJ+HPS` State Farm Fire and Casualty Company (J[P]P[PLZH[*VTT\UP[`*LU[LY State Farm General Insurance Company, Bloomington, IL 5VY[O4HPU:[(]PSSH *VU[HJ[*YHPN7YVR\WLR^^^WYV]LUHVYNZHJYLKOLHY[ 0901145.1 2 • March 11 - March 17, 2012 • THE NEWS SUN • THE HERALD REPUBLICAN • THE STAR A mother scorned Judd do it: 'Missing' brings big-screen action on the small screen whatever it takes to find her son. Her before. Kyla Brewer journey forces her to confront old She got her first real break when TV Media wounds and rely on old friends if she she was cast as Reed in the NBC has any hope of getting Michael back drama "Sisters," and from there, left he line between big screen and alive. -

Words and Images Matter NETWORK RESPONSIBILITY INDEX TABLE of CONTENTS

A COMPREHENSIVE ANALYSIS OF TELEVISION’S LESBIAN, GAY, BISEXUAL, AND TRANSGENDER IMAGES. words and images matter NETWORK RESPONSIBILITY INDEX TABLE OF CONTENTS • TABLE OF CONTENTS TK EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 ABC 8 CBS 10 CW 12 FOX 14 NBC 16 ABC FAMILY 18 FX 20 HBO 22 HISTORY 24 MTV 26 SHOWTIME 28 TBS 31 TLC 32 TNT 34 USA 36 MORE CABLE NETWORKS 38 BIOS 41 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The GLAAD Network Responsibility Index (NRI) is an evaluation of the quantity and quality of images of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgen- der (LGBT) people on television. It is intended to serve as a road map toward increasing fair, accurate, and inclusive LGBT media representations. GLAAD has seen time and again how images of multi-dimensional gay and transgender people on television have the power to change public percep- tions. The Pulse of Equality Survey, commissioned by GLAAD and conducted by Harris Interactive, confirmed a growing trend toward greater acceptance among the American public. Among the 19% who reported that their feelings toward gay and lesbian people have become more favorable over the past 5 years, 34% cited “seeing gay or lesbian characters on television” as a contrib- uting factor. In fact when Vice President Joe Biden endorsed marriage equality this year, he cited the NBC sitcom Will & Grace as one of the factors that led to a better understanding of the LGBT community by the American public. As diverse LGBT images in the media become more prevalent, the general public becomes exposed to the truth of the LGBT community: lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender Americans are parents and teachers, law enforce- ment and soldiers, high school students and loving elderly couples.