Schiller's Don Carlos in a Version by Mike Poulton, Directed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bring up the Bodies

BRING UP THE BODIES BY HILARY MANTEL ADAPTED FOR THE STAGE BY MIKE POULTON DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE INC. BRING UP THE BODIES Copyright © 2016, Mike Poulton and Tertius Enterprises Ltd Copyright © 2014, Mike Poulton and Tertius Enterprises Ltd Bring Up the Bodies Copyright © 2012, Tertius Enterprises Ltd All Rights Reserved CAUTION: Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that performance of BRING UP THE BODIES is subject to payment of a royalty. It is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America, and of all countries covered by the International Copyright Union (including the Dominion of Canada and the rest of the British Commonwealth), and of all countries covered by the Pan-American Copyright Convention, the Universal Copyright Convention, the Berne Convention, and of all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations. All rights, including without limitation professional/amateur stage rights, motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, video or sound recording, all other forms of mechanical, electronic and digital reproduction, transmission and distribution, such as CD, DVD, the Internet, private and file-sharing networks, information storage and retrieval systems, photocopying, and the rights of translation into foreign languages are strictly reserved. Particular emphasis is placed upon the matter of readings, permission for which must be secured from the Author’s agent in writing. The English language stock and amateur stage performance rights in the United States, its territories, possessions and Canada for BRING UP THE BODIES are controlled exclusively by DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., 440 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016. -

Education at the Races

News GLOBE TO OPEN SAM WANAMAKER PLAYHOUSE NICHOLAS HYTNER WITH NON-SHAKESPEARE PERFORMANCES TO LEAVE NATIONAL Curriculum THEATRE IN 2015 focus with Patrice Baldwin Sir Nicholas Hytner is to step down as artistic director at the National Theatre after more than a decade at the helm. Announcing his Education at ‘the races’ departure, Hytner said: ‘It’s been a joy and a privilege to lead the At the education race course, tension is mounting. The subject horses National Theatre for ten years and I’m looking forward to the next two. that have been allowed to compete will all be running very soon. Some ‘I have the most exciting and most fulfilling job in the English- have the usual head start, some are kept lame and may not be allowed speaking theatre; and after 12 years it will be time to give someone to enter the main race at all. What happens behind the scenes in various else a turn to enjoy the company of my stupendous colleagues, who stables is already determining the subject and GCSE winners, and the together make the National what it is.’ odds are low on drama being allowed to compete fairly in the race. Hytner came to the National Theatre as the successor of Sir Trevor Drama continues to be held back. Michael Gove is apparently Nunn in 2003. He has since headed up some of the National’s most avoiding having to get an act of parliament passed, which is needed commercially successful work to date, including The History Boys, were he to change the basic structure of the current national curriculum One Man, Two Guvnors and War Horse. -

Don Carlos and Mary Stuart 1St Edition Pdf Free

DON CARLOS AND MARY STUART 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Friedrich Schiller | 9780199540747 | | | | | Don Carlos and Mary Stuart 1st edition PDF Book Don Carlos and Mary Stuart , two of German literature's greatest historical dramas, deal with the timeless issues of power, freedom, and justice. Showing It is an accessible Mary Stuart for modern audiences. Rather, the language is more colloquial and the play exhibits some extensive cuts. The title is wrong. I have not read much by Schiller as of yet, but I feel really inspired to pick up more plays now. A pair of tragedies from Friedrich Schiller, buddy to Goethe, and child of the enlightenment. June Click [show] for important translation instructions. As a global organization, we, like many others, recognize the significant threat posed by the coronavirus. Don Carlos and Mary Stuart. I am particularly impressed by Schiller, a Protestant, for his honest account of the good Queen Mary and the Roman religion. I've read several translations of this text, but this is the one I can most readily hear in the mouths of actors, especially Act 3, when the two women come face to face. This article on a play from the 18th century is a stub. Please contact our Customer Service Team if you have any questions. These are two powerful dramas, later turned into equally powerful operas. The Stage: Reviews. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Peter Oswald London: Oberon Books, , 9. Mary Stuart. Don Carlos is a bit too long, I think, though it is fantastic. Archived from the original on September 8, Jan 01, Glenn Daniel Marcus rated it really liked it. -

Saturday, March 14, 7:30Pm, Sunday, March 15, 3Pm, Friday, March 20, 7:30Pm & Saturday, March 21, 3Pm

Starring the future, today! Book by Music & Lyrics by JOHN CAIRD STEPHEN SCHWARTZ Based on a concept by CHARLES LISANBY Orchestrations by BRUCE COUGHLIN & MARTIN ERSKINE Saturday, March 14, 7:30pm, Sunday, March 15, 3pm, Friday, March 20, 7:30pm & Saturday, March 21, 3pm Children of Eden TMTO sponsored by Season sponsored by from CRATERIAN PERFORMANCES presents the the EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR ur story begins in the beginning, with God’s creative nature and desire to be in relationship with his children. OPerhaps you don’t believe in the Biblical narrative (with which Stephen Schwartz, as composer and storyteller, takes consider- production of able liberties), but you might have children and find “Father’s” hopes and desires for his children relatable. Or perhaps you have siblings. You certainly have parents. And so, one way or another, you’re included in this story. It’s about you. It’s about all of us. It’s about our frailties and foibles, our struggles and failures, and it’s about our curiosity, ambitions and determination to live life the way we choose. It is also, like the Bible itself, ultimately a story about hope, love and redemption. When we don’t measure up, it takes someone else’s love us to lift us up. The meaning and message in all of this is timeless, and so director Cailey McCandless cast a vision for the show that unmoors it from ancient settings. And you might notice there are very few parallel lines in the show’s design... mostly intersecting angles, because life and our relationships tend to work that way. -

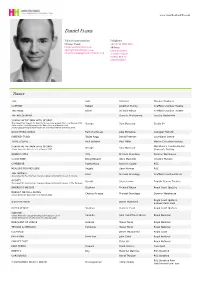

Daniel Evans

www.hamiltonhodell.co.uk Daniel Evans Talent Representation Telephone Christian Hodell +44 (0) 20 7636 1221 [email protected], Address [email protected], Hamilton Hodell, [email protected] 20 Golden Square London, W1F 9JL, United Kingdom Theatre Title Role Director Theatre/Producer COMPANY Robert Jonathan Munby Sheffield Crucible Theatre THE PRIDE Oliver Richard Wilson Sheffield Crucible Theatre THE ART OF NEWS Dominic Muldowney London Sinfonietta SUNDAY IN THE PARK WITH GEORGE Tony Award Nomination for Best Performance by a Lead Actor in a Musical 2008 George Sam Buntrock Studio 54 Outer Critics' Circle Nomination for Best Actor in a Musical 2008 Drama League Awards Nomination for Distinguished Performance 2008 GOOD THING GOING Part of a Revue Julia McKenzie Cadogan Hall Ltd SWEENEY TODD Tobias Ragg David Freeman Southbank Centre TOTAL ECLIPSE Paul Verlaine Paul Miller Menier Chocolate Factory SUNDAY IN THE PARK WITH GEORGE Wyndham's Theatre/Menier George Sam Buntrock Olivier Award for Best Actor in a Musical 2007 Chocolate Factory GRAND HOTEL Otto Michael Grandage Donmar Warehouse CLOUD NINE Betty/Edward Anna Mackmin Crucible Theatre CYMBELINE Posthumous Dominic Cooke RSC MEASURE FOR MEASURE Angelo Sean Holmes RSC THE TEMPEST Ariel Michael Grandage Sheffield Crucible/Old Vic Nominated for the 2002 Ian Charleson Award (Joint with his part in Ghosts) GHOSTS Osvald Steve Unwin English Touring Theatre Nominated for the 2002 Ian Charleson Award (Joint with his part in The Tempest) WHERE DO WE LIVE Stephen Richard -

Schiller and Music COLLEGE of ARTS and SCIENCES Imunci Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures

Schiller and Music COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES ImUNCI Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures From 1949 to 2004, UNC Press and the UNC Department of Germanic & Slavic Languages and Literatures published the UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures series. Monographs, anthologies, and critical editions in the series covered an array of topics including medieval and modern literature, theater, linguistics, philology, onomastics, and the history of ideas. Through the generous support of the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, books in the series have been reissued in new paperback and open access digital editions. For a complete list of books visit www.uncpress.org. Schiller and Music r.m. longyear UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures Number 54 Copyright © 1966 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons cc by-nc-nd license. To view a copy of the license, visit http://creativecommons. org/licenses. Suggested citation: Longyear, R. M. Schiller and Music. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1966. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.5149/9781469657820_Longyear Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Longyear, R. M. Title: Schiller and music / by R. M. Longyear. Other titles: University of North Carolina Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures ; no. 54. Description: Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, [1966] Series: University of North Carolina Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures. | Includes bibliographical references. Identifiers: lccn 66064498 | isbn 978-1-4696-5781-3 (pbk: alk. paper) | isbn 978-1-4696-5782-0 (ebook) Subjects: Schiller, Friedrich, 1759-1805 — Criticism and interpretation. -

English 252: Theatre in England 2006-2007 * [Optional Events

English 252: Theatre in England 2006-2007 * [Optional events — seen by some] Wednesday December 27 *2:30 p.m. Guys and Dolls (1950). Dir. Michael Grandage. Music & lyrics by Frank Loesser, Book by Jo Swerling and Abe Burrows. Based on a story and characters of Damon Runyon. Designer: Christopher Oram. Choreographer: Rob Ashford. Cast: Alex Ferns (Nathan Detroit), Samantha Janus (Miss Adelaide), Amy Nuttal (Sarah Brown), Norman Bowman (Sky Masterson), Steve Elias (Nicely Nicely Johnson), Nick Cavaliere (Big Julie), John Conroy (Arvide Abernathy), Gaye Brown (General Cartwright), Jo Servi (Lt. Brannigan), Sebastien Torkia (Benny Southstreet), Andrew Playfoot (Rusty Charlie/ Joey Biltmore), Denise Pitter (Agatha), Richard Costello (Calvin/The Greek), Keisha Atwell (Martha/Waitress), Robbie Scotcher (Harry the Horse), Dominic Watson (Angie the Ox/MC), Matt Flint (Society Max), Spencer Stafford (Brandy Bottle Bates), Darren Carnall (Scranton Slim), Taylor James (Liverlips Louis/Havana Boy), Louise Albright (Hot Box Girl Mary-Lou Albright), Louise Bearman (Hot Box Girl Mimi), Anna Woodside (Hot Box Girl Tallulha Bloom), Verity Bentham (Hotbox Girl Dolly Devine), Ashley Hale (Hotbox Girl Cutie Singleton/Havana Girl), Claire Taylor (Hot Box Girl Ruby Simmons). Dance Captain: Darren Carnall. Swing: Kate Alexander, Christopher Bennett, Vivien Carter, Rory Locke, Wayne Fitzsimmons. Thursday December 28 *2:30 p.m. George Gershwin. Porgy and Bess (1935). Lyrics by DuBose Heyward and Ira Gershwin. Book by Dubose and Dorothy Heyward. Dir. Trevor Nunn. Design by John Gunter. New Orchestrations by Gareth Valentine. Choreography by Kate Champion. Lighting by David Hersey. Costumes by Sue Blane. Cast: Clarke Peters (Porgy), Nicola Hughes (Bess), Cornell S. John (Crown), Dawn Hope (Serena), O-T Fagbenie (Sporting Life), Melanie E. -

David Yelland Photo: Catherine Shakespeare Lane

Paddock Suite, The Courtyard, 55 Charterhouse Street, London, EC1M 6HA p: + 44 (0) 20 73360351 e: [email protected] Phone: + 44 (0) 20 73360351 Email: [email protected] David Yelland Photo: Catherine Shakespeare Lane Eastern European, Scandinavian, Location: London Appearance: White Height: 5'11" (180cm) Other: Equity Weight: 13st. 6lb. (85kg) Eye Colour: Blue Playing Age: 51 - 65 years Hair Length: Mid Length Stage Stage, Cardinal Von Galen, All Our Children, Jermyn Street Theatre, Stephen Unwin Stage, Antigonus, The Winter's Tale, Globe Theatre, Michael Longhurst Stage, Lord Clifford Allen, Taken At Midnight, Chichester Festival Theatre & Haymarket Theatre, Jonathan Church Stage, Earl of Caversham, An Ideal Husband, Gate Theatre, Ethan McSweeney Stage, Sir George Crofts, Mrs Warren's Profession, Gate Theatre, Dublin, Patrick Mason Stage, Selwyn Lloyd, A Marvellous Year For Plums, Chichester Festival Theatre, Philip Franks Stage, Serebryakov, Uncle Vanya, The Print Room, Lucy Bailey Stage, King Henry, Henry IV Parts 1&2, Theatre Royal Bath & Tour, Sir Peter Hall Stage, Anthony Blunt, Single Spies, The Watermill, Jamie Glover Stage, Crofts, Mrs Warren's Profession, Theatre Royal Bath & West End, Michael Rudman Stage, President of the Court, For King & Country, Matthew Byam shaw, Tristram Powell Stage, Clive, The Circle, Chichester Festival Theatre, Jonathan Church Stage, Ralph Nickleby, Nicholas Nickleby, Chichester Festival Theatre,Gielgud , and Toronto, Philip Franks, Jonathan Church Stage, Wilfred Cedar, For Services Rendered, The Watermill -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Grillparzer's adoption and adaptation of the philosophy and vocabulary of Weimar classicism Roe, Ian Frank How to cite: Roe, Ian Frank (1978) Grillparzer's adoption and adaptation of the philosophy and vocabulary of Weimar classicism, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7954/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Summary After a summary of German Classicism and of Grillparzer's at times confusing references to it, the main body of the thesis aims to assess Grillparzer's use of the philosophy and vocahulary of Classicism, with particular reference to his ethical, social and political ideas, Grillparzer's earliest work, including Blanka, leans heavily on Goethe and Schiller, but such plagiarism is avoided after 1810. Following the success of Ahnfrau, however, Grillparzer returns to a much more widespread use of Classical themes, motifs and vocabulary, especially in Sappho, Grillparzer's mood in the period 1816-21 was one of introversion and pessimism, and there is an emphasis on the vocabulary of quiet peace and withdrawal. -

What I Learn from Theatregoing: Review Haiku

What I Learn from Theatregoing: Review Haiku Monica Prendergast1 University of Victoria [email protected] Abstract A haiku suite of theatre reviews and reflection on application to practice as drama educator and scholar. Keywords: poetic inquiry, theatre reviews, reflective practice, haiku 1 Biographical statement: Monica Prendergast is Associate Professor of drama/theatre education at the University of Victoria. She has published her poetic inquiry widely including two edited collections and two special issues. Monica also researches aspects of drama/theatre curriculum and pedagogy. Her latest project involves the development and implementation of a new performance studies curriculum for secondary students. What I Learn From Theatregoing: Review Haiku 292 Theatre is the most social of art forms, yet sharing the experience of theatre is often quite private. We might discuss the play we have seen for a few minutes with whomever has come with us and then life moves on. If we see a show alone (as I often do when travelling) our response is a soliloquy; a silent dialogue with ourselves. We may read, see or hear a review and allow the critic his or her privileged public monologue that is rarely responded to or challenged. Here, I invite you to share your responses to any or all of these review haiku created in response to theatre productions I have seen in Toronto, London, Stratford-Upon- Avon and New York in the past two to three years. I have been a freelance theatre reviewer for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation since 2006. For over nine years now I have shared my responses to local theatre and opera productions with listeners of CBC Radio’s On the Island morning program. -

1 Schiller and the Young Coleridge

Notes 1 Schiller and the Young Coleridge 1. For the details of Schiller’s career and thought I am drawing on a number of works including Lesley Sharpe, Friedrich Schiller: Drama, Thought and Politics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991); Walter Schafarschik, Friedrich Schiller (Stuttgart: Philipp Reclam, 1999); F. J. Lamport, German Classical Drama: Theatre, Humanity, and Nation, 1750–1870 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990); and T. J. Reed, The Classical Centre: Goethe and Weimar, 1775–1832 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), and Schiller- Handbuch, ed. Helmut Koopmann (Stuttgart: Alfred Kröner, 1998). 2. Schiller later revised the essay and published it in his Shorter Works in Prose under the title ‘The Stage Considered as a Moral Institution’ (‘Die Schaubühne als eine moralische Anstalt betrachtet’). 3. See David Pugh, ‘“Die Künstler”: Schiller’s Philosophical Programme’, Oxford German Studies, 18/19 (1989–90), 13–22. 4. See J. M. Ellis, Schiller’s ‘Kalliasbriefe’ and the Study of his Aesthetic Theory (The Hague and Paris: Mouton, 1969). 5. See Paul Robinson Sweet, Wilhelm von Humboldt: a Biography, 2 vols (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1978–80) and W. H. Bruford, The Ger- man Tradition of Self-Cultivation: ‘Bildung’ from Humboldt to Thomas Mann (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1975), ch. 1; also E. S. Shaffer, ‘Romantic Philosophy and the Organization of the Disciplines: the Found- ing of the Humboldt University of Berlin’, in Romanticism and the Sciences, ed. Andrew Cunningham and Nicholas Jardine (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), 38–54. 6. Norbert Oellers, Schiller: Geschichte seiner Wirkung bis zu Goethes Tod, 1805– 1832 (Bonn: Bouvier, 1967). -

History Made Manifest Acclaimed Adaptation of Hilary Mantel’S Booker Prize-Winning Novels, Published Bynick Hern Books and 4Th Estate Alongside RSC Premiere

History made manifest Acclaimed adaptation of Hilary Mantel’s Booker Prize-winning novels, published byNick Hern Books and 4th Estate alongside RSC premiere 2014 / 1 / WOLF HALL & BRING UP THE BODIES by Hilary Mantel, adapted by Mike Poulton Thomas Cromwell. Son of a blacksmith, political genius, briber, charmer, bully. A man with a deadly expertise in manipulating people and events. 15 Mike Poulton’s acclaimed two-part adaptation of Hilary Mantel’s Booker Prize- winning novels Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies is a thrilling and utterly convincing portrait of a brilliant man embroiled in the lethal, high-stakes politics of the court of Henry VIII. A co-publication between Nick Hern Books and 4th Estate, this single volume contains both acclaimed plays, an introduction by Mike Poulton, and forty-five pages of new, exclusive notes by original author Hilary Mantel on each of the principal characters, offering a unique insight into the plays and an invaluable resource to any theatre company wishing to stage them. ‘a bold, unforgettable lesson in history and politics’ The Times ‘brings the intrigues and political machinations to the stage with clarity, wit and plenty of very welcome humour… a real gem of a script for audiences and actors alike’ WhatsOnStage ‘superb… the mother of all costume dramas’ Daily Mail World Premiere: Royal Shakespeare Company at the Swan Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, 8 January-29 March 2014, directed by Jeremy Herrin Print ISBN: 978 0 00754 989 4 • Ebook ISBN: 978 0 00754 990 0 £10.99 • Script available now Hilary Mantel is an English novelist and short-story writer, best known for her Booker Prize-winning historical novels Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies.