A Chorus Line: Does It Abide by Rules Established by Actors' Equity Association for the Audition Process?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crittendon Et Al V. International Follies, Inc. Et Al

Case 1:18-cv-02185-ELR Document 1 Filed 05/16/18 Page 1 of 32 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA ATLANTA DIVISION CRYSTAL CRITTENDON, ) SHALEAH DAYE, RIANA EAST, ) CASSIDY GATES, JOVANA ) CIVIL ACTION GIBBS-ARNOLD, ASHLEY ) FILE NO. 1:18-mi-99999 HAYES, MERRIAH ) HILLARD, ASHLEY JOHNSON, ) TIFFANY LOWE, JASMINE ROSS, ) JASMINE THOMAS, MEGAN ) THOMAS, and SAMANTHA ) WILLIAMS, individually and on ) FLSA COLLECTIVE ACTION behalf of those similarly situated ) and LINDSEY CROOME, NICOLE ) MILLER-JORDAN and AVIA ) JURY TRIAL DEMANDED SHLTON individually only, ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) ) INTERNATIONAL FOLLIES, INC. ) d/b/a Cheetah and JACK BRAGLIA, ) ) Defendants. ) COMPLAINT COME NOW, CRYSTAL CRITTENDON, SHALEAH DAYE, RIANA EAST, CASSIDY GATES, JOVANA GIBBS-ARNOLD, ASHLEY HAYES, MERRIAH HILLARD, ASHLEY JOHNSON, TIFFANY LOWE, -1- Case 1:18-cv-02185-ELR Document 1 Filed 05/16/18 Page 2 of 32 JASMINE ROSS, JASMINE THOMAS, MEGAN THOMAS, SAM WILLIAMS, Individually and on behalf of those similarly situated, and LINDSEY CROOME, NICOLE MILLER-JORDAN and AVIA SHELTON, individually and files their Complaint against INTERNATIONAL FOLLIES, INC. d/b/a Cheetah and JACK BRAGLIA and show: INTRODUCTION 1. Plaintiffs are former or current employees of INTERNATIONAL FOLLIES, INC. (“Cheetah”). 2. Cheetah operates an adult entertainment club in Atlanta, Fulton County, Georgia known as the “Cheetah.” 3. JACK BRAGLIA (“Braglia”) is the general manager of Cheetah and part owner of Cheetah. 4. Cheetah failed to pay Plaintiffs and other similarly situated entertainers the minimum wage and overtime wage for all hours worked in violation of 29 U.S.C. §§ 206 and 207 of the Fair Labor Standards Act, 29 U.S.C. -

Clark Spring Semester 2020 Homeschoole MT

Clark Spring Semester 2020 Homeschoole MT JENNA: In the early 1940s, Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein III’s ‘Oklahoma!,’ adapted from a play written by Claremore playwright Lynn Riggs, opened on Broadway. It was the first musical they wrote together.. KYLE: Each had already found success on Broadway: Rodgers, having written a series of popular musicals with lyricist Lorenz Hart, and Hammerstein, having written the monumental classic, ‘Show Boat.’ But together with ‘Oklahoma!', they would change musical theatre forever. “Oh! What a Beautiful Mornin’” There's a bright golden haze on the meadow There's a bright golden haze on the meadow The corn is as high as an elephant's eye And it looks like it's climbing clear up to the sky Oh, what a beautiful mornin' Oh, what a beautiful day I've got a beautiful feeling Everything's going my way All the cattle are standing like statues All the cattle are standing like statues They don't turn their heads as they see me ride by But a little brown maverick is winking her eye Oh, what a beautiful mornin' I've got a beautiful feeling Everything's going my way All the sounds of the earth are like music All the sounds of the earth are like music The breeze is so busy, it don't miss a tree And an old weeping willow is laughing at me Oh, what a beautiful mornin' Oh, what a beautiful day I've got a beautiful feeling Everything's going my way Oh, what a beautiful day ALEXA I: With its character-driven songs and innovative use of dance, ‘Oklahoma’ elevated how musicals were written. -

PLAYHOUSE SQUARE January 12-17, 2016

For Immediate Release January 2016 PLAYHOUSE SQUARE January 12-17, 2016 Playhouse Square is proud to announce that the U.S. National Tour of ANNIE, now in its second smash year, will play January 12 - 17 at the Connor Palace in Cleveland. Directed by original lyricist and director Martin Charnin for the 19th time, this production of ANNIE is a brand new physical incarnation of the iconic Tony Award®-winning original. ANNIE has a book by Thomas Meehan, music by Charles Strouse and lyrics by Martin Charnin. All three authors received 1977 Tony Awards® for their work. Choreography is by Liza Gennaro, who has incorporated selections from her father Peter Gennaro’s 1977 Tony Award®-winning choreography. The celebrated design team includes scenic design by Tony Award® winner Beowulf Boritt (Act One, The Scottsboro Boys, Rock of Ages), costume design by Costume Designer’s Guild Award winner Suzy Benzinger (Blue Jasmine, Movin’ Out, Miss Saigon), lighting design by Tony Award® winner Ken Billington (Chicago, Annie, White Christmas) and sound design by Tony Award® nominee Peter Hylenski (Rocky, Bullets Over Broadway, Motown). The lovable mutt “Sandy” is once again trained by Tony Award® Honoree William Berloni (Annie, A Christmas Story, Legally Blonde). Musical supervision and additional orchestrations are by Keith Levenson (Annie, She Loves Me, Dreamgirls). Casting is by Joy Dewing CSA, Joy Dewing Casting (Soul Doctor, Wonderland). The tour is produced by TROIKA Entertainment, LLC. The production features a 25 member company: in the title role of Annie is Heidi Gray, an 11- year-old actress from the Augusta, GA area, making her tour debut. -

2019 Silent Auction List

September 22, 2019 ………………...... 10 am - 10:30 am S-1 2018 Broadway Flea Market & Grand Auction poster, signed by Ariana DeBose, Jay Armstrong Johnson, Chita Rivera and others S-2 True West opening night Playbill, signed by Paul Dano, Ethan Hawk and the company S-3 Jigsaw puzzle completed by Euan Morton backstage at Hamilton during performances, signed by Euan Morton S-4 "So Big/So Small" musical phrase from Dear Evan Hansen , handwritten and signed by Rachel Bay Jones, Benj Pasek and Justin Paul S-5 Mean Girls poster, signed by Erika Henningsen, Taylor Louderman, Ashley Park, Kate Rockwell, Barrett Wilbert Weed and the original company S-6 Williamstown Theatre Festival 1987 season poster, signed by Harry Groener, Christopher Reeve, Ann Reinking and others S-7 Love! Valour! Compassion! poster, signed by Stephen Bogardus, John Glover, John Benjamin Hickey, Nathan Lane, Joe Mantello, Terrence McNally and the company S-8 One-of-a-kind The Phantom of the Opera mask from the 30th anniversary celebration with the Council of Fashion Designers of America, designed by Christian Roth S-9 The Waverly Gallery Playbill, signed by Joan Allen, Michael Cera, Lucas Hedges, Elaine May and the company S-10 Pretty Woman poster, signed by Samantha Barks, Jason Danieley, Andy Karl, Orfeh and the company S-11 Rug used in the set of Aladdin , 103"x72" (1 of 3) Disney Theatricals requires the winner sign a release at checkout S-12 "Copacabana" musical phrase, handwritten and signed by Barry Manilow 10:30 am - 11 am S-13 2018 Red Bucket Follies poster and DVD, -

Into the Woods Is Presented Through Special Arrangement with Music Theatre International (MTI)

PREMIER SPONSOR ASSOCIATE SPONSOR MEDIA SPONSOR Music and Lyrics by Book by Stephen Sondheim James Lapine June 28-July 13, 2019 Originally Directed on Broadway by James Lapine Orchestrations by Jonathan Tunick Original Broadyway production by Heidi Landesman Rocco Landesman Rick Steiner M. Anthony Fisher Frederic H. Mayerson Jujamcyn Theatres Originally produced by the Old Globe Theater, San Diego, CA. Scenic Design Costume Design Shoko Kambara† Megan Rutherford Lighting Design Puppetry Consultant Miriam Nilofa Crowe† Peter Fekete Sound Design Casting Director INTO The Jacqueline Herter Michael Cassara, CSA Woods Musical Director Choreographer/Associate Director Daniel Lincoln^ Andrea Leigh-Smith Production Stage Manager Production Manager Myles C. Hatch* Adam Zonder Director Michael Barakiva+ Into the Woods is presented through special arrangement with Music Theatre International (MTI). All authorized performance materials are also supplied by MTI. www.MTIShows.com Music and Lyrics by Book by STEPHEN JAMES Directed by SONDHEIM LAPINE MICHAEL * Member of Actor’s Equity Association, † USA - Member of Originally directed on Broadway by James LapineBARAKIVA the Union of Professional Actors and United Scenic Artists Orchestrations by Jonathan Tunick Stage Managers in the United States. Local 829. ^ Member of American Federation of Musicians, + Local 802 or 380. CAST NARRATOR ............................................................................................................................................HERNDON LACKEY* CINDERELLA -

“Kiss Today Goodbye, and Point Me Toward Tomorrow”

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Missouri: MOspace “KISS TODAY GOODBYE, AND POINT ME TOWARD TOMORROW”: REVIVING THE TIME-BOUND MUSICAL, 1968-1975 A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School At the University of Missouri In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy By BRYAN M. VANDEVENDER Dr. Cheryl Black, Dissertation Supervisor July 2014 © Copyright by Bryan M. Vandevender 2014 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled “KISS TODAY GOODBYE, AND POINT ME TOWARD TOMORROW”: REVIVING THE TIME-BOUND MUSICAL, 1968-1975 Presented by Bryan M. Vandevender A candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy And hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Dr. Cheryl Black Dr. David Crespy Dr. Suzanne Burgoyne Dr. Judith Sebesta ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I incurred several debts while working to complete my doctoral program and this dissertation. I would like to extend my heartfelt gratitude to several individuals who helped me along the way. In addition to serving as my dissertation advisor, Dr. Cheryl Black has been a selfless mentor to me for five years. I am deeply grateful to have been her student and collaborator. Dr. Judith Sebesta nurtured my interest in musical theatre scholarship in the early days of my doctoral program and continued to encourage my work from far away Texas. Her graduate course in American Musical Theatre History sparked the idea for this project, and our many conversations over the past six years helped it to take shape. -

Musical Theatre Performance

REQUIREMENTS FOR THE BACHELOR OF FINE ARTS IN MUSICAL THEATRE WEITZENHOFFER FAMILY COLLEGE OF FINE ARTS THE UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA CREDIT HOURS AND GRADE AVERAGES REQUIRED Musical Theatre For Students Entering the Total Credit Hours . 120-130 Performance Oklahoma State System Minimum Overall Grade Point Average . 2.50 for Higher Education Minimum Grade Point Average in OU Work . 2.50 B737 Summer 2014 through A grade of C or better is required in all courses taken within the College of Fine Arts. Bachelor of Fine Arts Spring 2015 Bachelor’s degrees require a minimum of 40 hours of upper-division (3000-4000) coursework. in Musical Theatre OU encourages students to complete at least 32-35 hours of applicable coursework each year to have the opportunity to graduate in four years. Audition is required for admission to the degree program. General Education Requirements (34-44 hours) Hours Major Requirements (86 hours) Core I: Symbolic and Oral Communication Musical Theatre Performance (14 hours) Musical Theatre Support (14 hours) ENGL 1113, Principles of English Composition 3 MTHR 2122, Auditions 2 MTHR 3143, History of American 3 ENGL 1213, Principles of English Composition, or 3 MTHR 3142, Song Study I 2 Musical Theatre (Core IV) EXPO 1213, Expository Writing MTHR 3152, Song Study II 2 MTHR 4183, Capstone Experience 3 MTHR 3162, Repertoire 2 (Core V) Foreign Language—this requirement is not mandatory if the 0-10 MTHR 3172, Roles 2 Musical Theatre Electives (six of these 8 student successfully completed 2 years of the same foreign MTHR 3182, Musical Scenes I 2 eight hours must be upper-division) language in high school. -

KS5 Exploring Performance Styles in Musical Theatre

Exploring performance KS5 styles in Musical Theatre Heidi McEntee Heidi McEntee is a Dance and KS5 – BTEC LEVEL 3, UNIT D10 Performing Arts specialist based in the Midlands. She has worked in education for over fifteen years delivering a variety of Dance and Performing Arts qualifications at Introduction Levels 1, 2 and 3. She is a Senior Unit D10: Exploring Performance Styles is one of the three units which sit within Module D: Assessment Associate working on musical theatre Skills Development from the new BTEC Level 3 in Performing Arts Practice Performing Arts qualifications and (musical theatre) qualification. This scheme of work focuses on the first unit which introduces a contributing author for student and explores different musical theatre styles. revision guides. This unit requires learners to develop their practical skills in dance, acting and singing while furthering their understanding of musical theatre styles. The unit culminates in a performance of two extracts in two different styles of musical theatre as well as a critical review of the stylistic qualities within these extracts. This scheme of work provides a suggested approach to six weeks of introductory classes, as a part of a full timetable, which explores the development of performance styles through the history of musical theatre via practical activities, short projects and research tasks. Learning objectives By the end of this scheme, learners will have: § Investigated the history of musical theatre and the factors which have influenced its development Unit D10: Exploring Performance § Explored the characteristics of different musical theatre styles and how they have developed Styles from BTEC L3 Nationals over time Performing Arts Practice (musical § Applied stylistic conventions to the performance of material theatre) (2019) § Examined professional work through critical analysis. -

Grasso on Chervinsky

Lindsay M. Chervinsky. The Cabinet: George Washington and the Creation of an American Institution. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2020. 432 pp. $29.95, cloth, ISBN 978-0-674-98648-0. Reviewed by Joanne S. Grasso (New York Institute of Technology) Published on H-Early-America (July, 2021) Commissioned by Troy Bickham (Texas A&M University) As a grand epic but over a shorter period of jor author of the Federalist Papers. And Bradford history, Lindsay M. Chervinsky’s The Cabinet served in the Revolutionary War and then went chronicles George Washington and the creation of into law. The Virginia dynasty of presidents was in the first US presidential cabinet. In this expansive the making: Jefferson first served as secretary of account of how Washington oversaw, constructed, state, James Madison in the House of Representat‐ and ultimately organized his cabinet, the author ives, and James Monroe as an ambassador. segments her book from his pre-presidency days, In the introduction, the author begins her nar‐ when he developed relationships and strategies, in rative with the grandiose ceremony of the inaugur‐ the chapter “Forged in War,” to the initial stages of ation of Washington as the first president of the the development of his cabinet in “The Cabinet United States and then discusses many of his ad‐ Emerges,” and all the way through to problems in ministration’s initial tasks and strategies. Wash‐ “A Cabinet in Crisis.” ington used the “advice and consent” clause found As depicted, some of the brightest and time- in the United States Constitution with respect to tested minds from the Revolutionary War era were the US Senate, which states that the president cabinet members, including Henry Knox, Edmund “shall have Power, by and with the Advice and Randolph, Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, Consent of the Senate, to make Treaties, provided and William Bradford. -

2018 Annual Report

Annual Report 2018 Dear Friends, welcome anyone, whether they have worked in performing arts and In 2018, The Actors Fund entertainment or not, who may need our world-class short-stay helped 17,352 people Thanks to your generous support, The Actors Fund is here for rehabilitation therapies (physical, occupational and speech)—all with everyone in performing arts and entertainment throughout their the goal of a safe return home after a hospital stay (p. 14). nationally. lives and careers, and especially at times of great distress. Thanks to your generous support, The Actors Fund continues, Our programs and services Last year overall we provided $1,970,360 in emergency financial stronger than ever and is here for those who need us most. Our offer social and health services, work would not be possible without an engaged Board as well as ANNUAL REPORT assistance for crucial needs such as preventing evictions and employment and training the efforts of our top notch staff and volunteers. paying for essential medications. We were devastated to see programs, emergency financial the destruction and loss of life caused by last year’s wildfires in assistance, affordable housing, 2018 California—the most deadly in history, and nearly $134,000 went In addition, Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS continues to be our and more. to those in our community affected by the fires and other natural steadfast partner, assuring help is there in these uncertain times. disasters (p. 7). Your support is part of a grand tradition of caring for our entertainment and performing arts community. Thank you Mission As a national organization, we’re building awareness of how our CENTS OF for helping to assure that the show will go on, and on. -

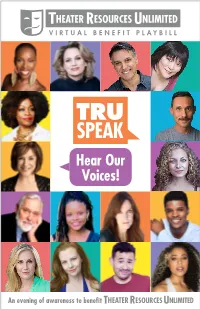

TRU Speak Program 021821 XS

THEATER RESOURCES UNLIMITED VIRTUAL BENEFIT PLAYBILL TRU SPEAK Hear Our Voices! An evening of awareness to benefit THEATER RESOURCES UNLIMITED executive producer Bob Ost associate producers Iben Cenholt and Joe Nelms benefit chair Sanford Silverberg plays produced by Jonathan Hogue, Stephanie Pope Lofgren, James Rocco, Claudia Zahn assistant to the producers Maureen Condon technical coordinator Iben Cenholt/RuneFilms editor-technologists Iben Cenholt/RuneFilms, Andrea Lynn Green, Carley Santori, Henry Garrou/Whitetree, LLC video editors Sam Berland/Play It Again Sam’s Video Productions, Joe Nelms art direction & graphics Gary Hughes casting by Jamibeth Margolis Casting Social Media Coordinator Jeslie Pineda featuring MAGGIE BAIRD • BRENDAN BRADLEY • BRENDA BRAXTON JIM BROCHU • NICK CEARLEY • ROBERT CUCCIOLI • ANDREA LYNN GREEN ANN HARADA • DICKIE HEARTS • CADY HUFFMAN • CRYSTAL KELLOGG WILL MADER • LAUREN MOLINA • JANA ROBBINS • REGINA TAYLOR CRYSTAL TIGNEY • TATIANA WECHSLER with Robert Batiste, Jianzi Colon-Soto, Gha'il Rhodes Benjamin, Adante Carter, Tyrone Hall, Shariff Sinclair, Taiya, and Stephanie Pope Lofgren as the Voice of TRU special appearances by JERRY MITCHELL • BAAYORK LEE • JAMES MORGAN • JILL PAICE TONYA PINKINS •DOMINIQUE SHARPTON • RON SIMONS HALEY SWINDAL • CHERYL WIESENFELD TRUSpeak VIP After Party hosted by Write Act Repertory TRUSpeak VIP After Party production and tech John Lant, Tamra Pica, Iben Cenholt, Jennifer Stewart, Emily Pierce Virtual Happy Hour an online musical by Richard Castle & Matthew Levine directed -

Leonard Bernstein's MASS

27 Season 2014-2015 Thursday, April 30, at 8:00 Friday, May 1, at 8:00 The Philadelphia Orchestra Saturday, May 2, at 8:00 Sunday, May 3, at 2:00 Leonard Bernstein’s MASS: A Theatre Piece for Singers, Players, and Dancers* Conducted by Yannick Nézet-Séguin Texts from the liturgy of the Roman Mass Additional texts by Stephen Schwartz and Leonard Bernstein For a list of performing and creative artists please turn to page 30. *First complete Philadelphia Orchestra performances This program runs approximately 1 hour, 50 minutes, and will be performed without an intermission. These performances are made possible in part by the generous support of the William Penn Foundation and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Additional support has been provided by the Presser Foundation. 28 I. Devotions before Mass 1. Antiphon: Kyrie eleison 2. Hymn and Psalm: “A Simple Song” 3. Responsory: Alleluia II. First Introit (Rondo) 1. Prefatory Prayers 2. Thrice-Triple Canon: Dominus vobiscum III. Second Introit 1. In nomine Patris 2. Prayer for the Congregation (Chorale: “Almighty Father”) 3. Epiphany IV. Confession 1. Confiteor 2. Trope: “I Don’t Know” 3. Trope: “Easy” V. Meditation No. 1 VI. Gloria 1. Gloria tibi 2. Gloria in excelsis 3. Trope: “Half of the People” 4. Trope: “Thank You” VII. Mediation No. 2 VIII. Epistle: “The Word of the Lord” IX. Gospel-Sermon: “God Said” X. Credo 1. Credo in unum Deum 2. Trope: “Non Credo” 3. Trope: “Hurry” 4. Trope: “World without End” 5. Trope: “I Believe in God” XI. Meditation No. 3 (De profundis, part 1) XII.