Government in Arkansas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Correspondence Courses/Concurrent Credit Available from Colleges and Universities

Correspondence Courses/Concurrent Credit Available from Colleges and Universities Pulaski Technical College ASU-Mountain Home Arkansas Northwestern College, 3000 West Scenic Drive 1600 South College Street Blytheville North Little Rock, Arkansas 72118 Mountain Home, AR 72653 2501 South Division St (501) 812-2200 (870) 508-6262 Blytheville, AR 72315 http://www.pulaskitech.edu https://www.asumh.edu/admission- (870) 762-1020 Grades: 9-12 registration/student-admission- http://www.anc.edu/stem/ checklists/concurrent-student.html UACCB Black River Technical College, PO Box 3350 Back River Technical College Paragould Batesville, AR 72503 P.O. Box 468 1 Black River Drive (870) 612-2053 / (800) 508-7878 Pocahontas, AR 72455 Paragould, AR 72450 http://www.uaccb.edu/concurrent- (870) 248-4157 (870) 239-0969 credit http://www.blackrivertech.org/pros http://www.blackrivertech.org/admissi pective-students/concurrent- on-registration-enrollment University of Arkansas Community enrollment College at Hope East Arkansas Community 2500 South Main University of Central Arkansas College, Forrest City Hope, AR 71802 201 Donaghey Ave. 1700 Newcastle Road (870) 722-8202 Conway, AR 72035 Forrest City, AR 72355 http://www.uacch.edu/?page_id=1858 (501) 450-3128 (870) 633-4480 http://uca.edu/admissions/apply/ http://www.eacc.edu/ Arkansas Tech University Office of Admissions & Student Arkansas Baptist College Phillips Community College of the Recruitment 1621 Martin Luther King Jr. Drive U of A in DeWitt, Helena-West 1605 Coliseum Drive, Suite 141 Little Rock, -

2021-2022 Academic Catalog May 14, 2021

1 Ecclesia College 2021-2022 Academic Catalog May 14, 2021 Ecclesia College 9653 Nations Drive Springdale, Arkansas 72762 (479) 248-7236 www.ecollege.edu 2021-2022 Academic Catalog 2 Ecclesia College is an equal opportunity institution. It does not discriminate based on race, sex, color, national or ethnic origin. Ecclesia College reserves the right to make changes in courses, policy, regulations and fees, as circumstances dictate subsequent to publication. 2021-2022 Academic Catalog 3 From the President Thank you for considering the benefits of an Ecclesia College education. We believe Ecclesia College offers a unique educational opportunity that differs substantially from what you might experience at a public institution. To begin, Ecclesia offers a biblical higher education. By this we mean that, regardless of their major, all students take a concentration of studies in Bible and theology. The Bible is God’s revelation to mankind. It contains information that cannot be discovered through human effort. Indeed, it provides guidance regarding how to relate to both our Creator and our fellows. A secular education deals only with matters that can be discovered through human effort. To be successful in life it is imperative to deal with reality. If we attempt to make decisions, but fail to take reality into account, our decisions will be flawed. Accordingly, we must be aware of both the truth that can be discovered through human effort and the truth that God has revealed in His message to humankind, the Bible. In our current world, change is occurring so rapidly that it is difficult to determine what the generation currently attending college will need during their lifetime. -

Academic Programs

1 Ecclesia College “Where Leaders Are Learning” 2014-2018 Catalog Revised Edition – August 10, 2017 Ecclesia College 9653 Nations Drive Springdale, Arkansas 72762 (479) 248-7236 www.ecollege.edu 2014-2018 Revised Academic Catalog 2 Ecclesia College is an equal opportunity institution. It does not discriminate based on race, sex, color, national or ethnic origin. Ecclesia College reserves the right to make changes in courses, policy, regulations and fees, as circumstances dictate subsequent to publication 2014-2018 Revised Academic Catalog 3 From the President Dear Student, Our world is changing. But we know that God’s ways have not changed and are still perfect. When it comes to shaping our minds, we are determined to follow His ways so that His purposes will be realized fully in our lives. God is very particular about the order of education He prescribes to us in II Peter 1:5-10. As we follow His educational prescription for knowledge, we arrive at an increasing understanding of Him, the Truth, Who sets us free. The Scriptures assert the proper foundation for knowledge is first “faith” and then “character.” Knowledge gained through any means, apart from the foundation of Christ, inevitably leads us to spiritual ignorance and eventual ruin. Begin with the wrong premise and you always will arrive at the wrong conclusion. We welcome you to pursue a quality faith and character-based education here at Ecclesia College. We emphasize, whatever your major, setting your mind on the things above so that you will be rooted and grounded in unshakable Truth. We will help equip you with godly knowledge, skills and credentials so that you can be both truly successful in your career and highly effective for His Kingdom in your sphere of influence. -

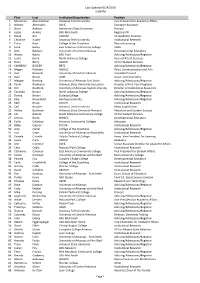

Last Updated 6/14/2016 9:49 AM Page 1

Last Updated 6/14/2016 9:49 AM First Last Institution/Organization Position 1 Mohamed Abdelrahman Arkansas Tech University Vice President for Academic Affairs 2 Nichole Abernathy ADHE Executive Assistant 3 Steve Adkison Henderson State University Provost 4 Leslie Anders ASU Mid-South Registrar/IR 5 Diana Arn UACCM VC Academic Services 6 Christine Austin Arkansas Tech University Institutional Research 7 Tricia Baar College of the Ouachitas Dean of Learning 8 Janie Bailey East Arkansas Community College VPAA 9 Amy Baldwin University of Central Arkansas Developmental Educators 10 Wyane Banks SAU Tech Advising/Admissions/Registrar 11 Laura Berry North Arkansas College Dean of Arts & Sciences 12 Brian Berry UACCH VC for Student Services 13 KIMBERLY BIGGER BRTC Advising/Admissions/Registrar 14 Megan Bolinder NWACC Dean, Communication and Arts 15 Kurt Boniecki University of Central Arkansas Associate Provost 16 Dale Bower UAM Assoc. Vice Chancellor 17 Meagan Bowling University of Arkansas Fort Smith Advising/Admissions/Registrar 18 Kim Bradford University of Arkansas System eVersity Director of Institutional Assurance 19 Tavonda Brown North Arkansas College Advising/Admissions/Registrar 20 Donna Brown Ecclesia College Advising/Admissions/Registrar 21 Jake Brownfield Harding University Advising/Admissions/Registrar 22 Beth Bruce UACCB Institutional Research 23 Carl Brucker Arkansas Tech University Head, English Dept. 24 Ashley Buchman Arkansas State University-Newport Retention and Student Success 25 Jim Bullock South Arkansas Community College VP for Student Services 26 Johnna Burns NWACC Developmental Educators 27 Collin Callaway Arkansas Community Colleges Advocate 28 Blake Cannon PCCUA Institutional Research 29 Amy Carter College of the Ouachitas Advising/Admissions/Registrar 30 Lisa Cater University of Arkansas at Monticello Institutional Research 31 Pamela Cicirello Pulaski Technical College Assoc. -

Seeding Results

2017 NCCAA Baseball World Series Host: Prasco Park May 24-27, 2017 Location: Mason, Ohio Seeding Pool A 1) Oklahoma Baptist University 4) Alice Lloyd College 5) Campbellsville University 8) Bluefield College 9) Ecclesia College Pool B 2) Emmanuel College 3) Bethesda University 6) Southwestern Christian University 7) Oakland City University 10) Hiwassee College Results 5/24/17 Game 1 Bethesda University def. Oakland City University 9-4 Game 2 Bluefield College def. Alice Lloyd College 7-1 Game 3 Southwestern Christian University def. Hiwassee College 10-0 Game 4 Campbellsville University def. Ecclesia College 8-2 5/25/17 Game 5 Campbellsville University def. Bluefield College 12-2 Game 6 Southwestern Christian University def. Oakland City University 9-2 Game 7 Oklahoma Baptist University def. Ecclesia College 15-3 Game 8 Emmanuel College def. Hiwassee College 11-4 Game 9 Bluefield College def. Ecclesia College 7-4 Game 10 Hiwassee College def. Oakland City 8-1 Game 11 Oklahoma Baptist University def. Alice Lloyd College 19-1 (7 inn.) Game 12 Emmanuel College def. Bethesda University 12-1 (8 inn.) 5/26/17 Game 13 Campbellsville University def. Alice Lloyd College 13-4 Game 14 Bethesda University def. Southwestern Christian University 9-1 Game 15 Emmanuel College def. Oakland City University 14-7 Game 16 Oklahoma Baptist University def. Bluefield College 13-1 Game 17 Bethesda University def. Hiwassee College 4-0 Game 18 Ecclesia College def. Alice Lloyd College 9-3 Game 19 Southwestern Christian University def. Emmanuel College 6-1 Game 20 Oklahoma Baptist University def. Campbellsville University 10-6 5/27/17 Semi 1 Oklahoma Baptist University def. -

2019-2020 Academic Catalog Revised November 15, 2019

1 Ecclesia College “Where Leaders Are Learning” 2019-2020 Academic Catalog Revised November 15, 2019 Ecclesia College 9653 Nations Drive Springdale, Arkansas 72762 (479) 248-7236 www.ecollege.edu 2019-2020 Academic Catalog 2 Ecclesia College is an equal opportunity institution. It does not discriminate based on race, sex, color, national or ethnic origin. Ecclesia College reserves the right to make changes in courses, policy, regulations and fees, as circumstances dictate subsequent to publication. 2019-2020 Academic Catalog 3 From the President Thank you for considering the benefits of an Ecclesia College education. We believe Ecclesia College offers a unique educational opportunity that differs substantially from what you might experience at a public institution. To begin, Ecclesia offers a biblical higher education. By this we mean that, regardless of their major, all students take a concentration of studies in Bible and theology. The Bible is God’s revelation to mankind. It contains information that cannot be discovered through human effort. Indeed, it provides guidance regarding how to relate to both our Creator and our fellows. A secular education deals only with matters that can be discovered through human effort. To be successful in life it is imperative to deal with reality. If we attempt to make decisions, but fail to take reality into account, our decisions will be flawed. Accordingly, we must be aware of both the truth that can be discovered through human effort and the truth that God has revealed in His message to humankind, the Bible. In our current world, change is occurring so rapidly that it is difficult to determine what the generation currently attending college will need during their lifetime. -

Ecclesia's Work-Learning Program Encourages

of all Work College graduates agree that their work program experience was an important way to reduce college costs. of all Work College graduates credit their work experience with making them effective problem solvers. WASHINGTON – The U.S. economy is in serious danger from a growing mismatch between the skills needed for jobs being created Ecclesia’s Work-Learning Program encourages and the educational backgrounds (or lack thereof) of would-be workers. Character The Ecclesia educational experience focuses on developing and living in good That is the conclusion of an analysis of character with Christ as the model. jobs data released by the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. The lead author stated the True Success Ecclesia prepares students for true success through an innovative integration of report should shake up colleges—and academics, work, internships, mentoring and other hands-on experiences. challenge most of them to be much more career-oriented and overhaul the way they educate students to more Debt Reduction Ecclesia is so committed to providing a Christian higher education, it will closely align the curriculum with spe- award a financial aid package offsetting tuition cost to every deserving student cific jobs and emphasize employability.¹ demonstrating need. Faith Integration Work College graduates report that “True knowledge comes on the foundation of faith and character” [2 Peter 1:5] their college better prepared is a fundamental conviction both in and out of the classroom. Ecclesia allows and them for their current job. supports discussions regarding student faith and core beliefs alongside traditional academics. as compared with their peers Mentoring for Life Every Ecclesia College student has a support system of faculty, administration and fellow students to assist and encourage them throughout life. -

Last Updated 6/14/2016 5:08 PM Page 1 1 Mohamed Abdelrahman

Last Updated 6/14/2016 5:08 PM First Last Institution/Organization Position 1 Mohamed Abdelrahman Arkansas Tech University Vice President for Academic Affairs 2 Nichole Abernathy ADHE Executive Assistant 3 Steve Adkison Henderson State University Provost 4 Leslie Anders ASU Mid-South Registrar/IR 5 Diana Arn UACCM VC Academic Services 6 Christine Austin Arkansas Tech University Institutional Research 7 Tricia Baar College of the Ouachitas Dean of Learning 8 Janie Bailey East Arkansas Community College VPAA 9 Amy Baldwin University of Central Arkansas Developmental Educators 10 Wyane Banks SAU Tech Advising/Admissions/Registrar 11 Laura Berry North Arkansas College Dean of Arts & Sciences 12 Brian Berry UACCH VC for Student Services 13 KIMBERLY BIGGER BRTC Advising/Admissions/Registrar 14 Megan Bolinder NWACC Dean, Communication and Arts 15 Kurt Boniecki University of Central Arkansas Associate Provost 16 Dale Bower UAM Assoc. Vice Chancellor 17 Meagan Bowling University of Arkansas Fort Smith Advising/Admissions/Registrar 18 Paula Bradberry Arkansas State University Jonesboro Director of First Year Programs 19 Kim Bradford University of Arkansas System eVersity Director of Institutional Assurance 20 Tavonda Brown North Arkansas College Advising/Admissions/Registrar 21 Donna Brown Ecclesia College Advising/Admissions/Registrar 22 Jake Brownfield Harding University Advising/Admissions/Registrar 23 Beth Bruce UACCB Institutional Research 24 Carl Brucker Arkansas Tech University Head, English Dept. 25 Ashley Buchman Arkansas State University-Newport Retention and Student Success 26 Jim Bullock South Arkansas Community College VP for Student Services 27 Johnna Burns NWACC Developmental Educators 28 Collin Callaway Arkansas Community Colleges Advocate 29 Blake Cannon PCCUA Institutional Research 30 Amy Carter College of the Ouachitas Advising/Admissions/Registrar 31 Lisa Cater University of Arkansas at Monticello Institutional Research 32 Pamela Cicirello Pulaski Technical College Assoc. -

DI Women's Basketball 2/27/2017 NCCAA Power School Region

DI Women's Basketball 2/27/2017 NCCAA Power School Region W L % Rating 1 Campbellsville University ME 25 5 83.3% 8.400 DNR 11/28 2 College of the Ozarks C 24 4 85.7% 7.839 3 Roberts Wesleyan College MW 17 11 60.7% 7.750 4 Cedarville University MW 18 10 64.3% 7.393 5 Mid-America Christian University C 19 10 65.5% 7.362 6 Emmanuel College S 14 12 53.8% 7.000 7 Colorado Christian University C 11 16 40.7% 6.963 DNR 1/30 8 Ohio Christian University MW 20 9 69.0% 6.897 9 Lancaster Bible College MW 18 7 72.0% 6.880 10 Bluefield College ME 18 12 60.0% 6.767 DNR 2/13 11 Indiana Wesleyan University MW 17 11 60.7% 6.732 12 Greenville College NC 17 8 68.0% 6.680 13 Southwestern Christian University C 15 13 53.6% 6.643 14 Judson University NC 18 12 60.0% 6.517 15 Grace College & Seminary MW 14 16 46.7% 6.483 16 Southwestern Assemblies of God University C 11 16 40.7% 6.481 17 University of Northwestern NC 17 8 68.0% 6.480 18 Belhaven University ME 14 11 56.0% 6.360 19 Oklahoma Baptist University C 9 19 32.1% 6.143 20 Trinity Christian College NC 16 14 53.3% 6.033 21 Bethel College NC 10 21 32.3% 5.984 22 Oakland City University MW 17 6 73.9% 5.913 23 McMurry University C 9 15 37.5% 5.813 24 Southern Wesleyan University S 6 20 23.1% 5.788 25 Warner University S 13 16 44.8% 5.759 DNR 11/28 & 1/16 26 Crowley's Ridge College C 12 18 40.0% 5.733 27 Hiwassee College ME 15 4 78.9% 5.632 28 Houghton College MW 11 14 44.0% 5.480 DNR 1/16 29 Trinity International University NC 8 21 27.6% 5.414 30 Morthland College ME 5 14 26.3% 5.316 32 Cincinnati Christian -

The Ouachita Circle Spring 2015 Ouachita Baptist University Ouachita Baptist University

Ouachita Baptist University Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita Alumni Magazine Ouachita Alumni Spring 2015 The Ouachita Circle Spring 2015 Ouachita Baptist University Ouachita Baptist University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/alumni_mag Recommended Citation University, Ouachita Baptist, "The Ouachita Circle Spring 2015" (2015). Alumni Magazine. Book 22. http://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/alumni_mag/22 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Ouachita Alumni at Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. It has been accepted for inclusion in Alumni Magazine by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DR. HORNE CONCLUDES OBU TENURE | ALUMNI PROFILE: ZIPADEE-ZIP TO SHARK TANK | PRUET PROFS “TEACH THE TEXT” Spring 2015 Spring 2015 PRESIDENT REX M. HORNE, JR. VICE PRESIDENT FOR COMMUNICATIONS / EDITOR TRENNIS HENDERSON CAMPUS NEWS UPDATE DIRECTOR OF COMMUNICATIONS & MARKETING / ASSOCIATE EDITOR BROOKE ZIMNY ASSISTANT DIRECTOR OF GRAPHIC SERVICES / CREATIVE DIRECTOR RENÉ ZIMNY VICE PRESIDENT FOR INSTITUTIONAL ADVANCEMENT KELDON HENLEY DIRECTOR OF ALUMNI JON MERRYMAN ALUMNI PROGRAM COORDINATOR HANNAH PILCHER The Ouachita Circle is a publication of Ouachita Baptist University’s alumni and communications offices. Printed by TCPrint Solutions in North Little Rock, Ark. © Copyright 2015 Cover photo by Tyler Rosenthal (‘15). SUBMIT ADDRESS CHANGES AND CLASS NOTES www.ouachitaalumni.org • [email protected] • (870) 245-5506 410 Ouachita St., OBU Box 3762 • Arkadelphia, AR 71998-0001 FOLLOW US @Ouachita @OuachitaAlumni photo by Tyler Rosenthal TIGER TRAKS MARKS 40 YEARS: BOARD OF TRUSTEES Jay Heflin (Chair), Mary Pat Anthony, Curtis Arnold, Millard CAMPUS COMPETITION CONTINUES Aud, Steven Collier, Clay Conly, Julie Dodge, Susie Everett, th Clay Hallmark, Richard Lusby, Terri Mardis, John McCallum, The Ouachita Student Foundation hosted Ouachita’s 40 Mollie Morgan, Beth Neeley, Mark Roberts, Lloydine Seale, Ken annual Tiger Traks competition on April 24-25. -

CRC Insider SERVICE Crowley’S Ridge College SPRING 2015 Paragould, Arkansas

SPIRITUA P L LIFE SCHOLARSHI CRC Insider SERVICE CROWLEY’S RIDGE COLLEGE SPRING 2015 PARAGOULD, ARKANSAS CRC Pioneers have record breaking season! see page 4 GOAL: $80,000 SPIRIT OF AMERICA XXII CRCCRCSunday, June DAYDAY 14, 2015 Friday, May 29, 2015 DINNER: 6:00 PM ProGram: 7:00 pm featuring CRC BIBLE MAJORS see page 3 and V.P./Dean Art Smith IN THIS EDITION: Pages 2-3 . Springboard to the Future by President Hoppe Pages 4-5 . CRC Students Having a Great Year Page 6 . Tips to Consider by Vice President Johnson Page 7 . CRC Projects Page 8 . Distinguished Alumnus Award, Homecoming, Haiti Trip JIM WHITE Pages 9-11 . Honor Roll of Donors, Memorials, Honors subject of the Disney movie “McFarland, USA” Page 12 . In Memory of Mangrum & Hoffman, CRC Alumni News see page 3 CRC’S 50TH YEAR – SPRINGBoard to THE FUTURE The Spring 2015 semester is by Owen and Wanda Jo Moseley on behalf of the quickly coming to an end. CRC’s Joe A. and Wanda H. Johnson Trust in the amount of Commencement Exercises will $487,500. This trust resulted from the estate planning of be on May 16, 2015 at 11:00AM Wanda Jo’s parents, Joe and Wanda Johnson. Joe passed from at the Hillcrest Church of Christ this life on September 21, 2013 and then Wanda on March 3, next door to campus. Emmett 2014. They were married for 74 years! Joe and Wanda began Floyd Smith III will deliver the Commencement Address. CRC officials thought it appropriate to invite the son of our Founder, Emmett Floyd Smith, Jr. -

2020 College Acceptances

2020 College Acceptances Abilene Christian University Olivet Nazarene University Arizona State University Ouachita Baptist University Arkansas Baptist College Pepperdine University Arkansas State University Regis University Arkansas Tech University Rhodes College Auburn University Samford University Austin Peay State University Azusa Pacific University San Diego State University Barnard College SCAD: The University for Creative Careers Baylor University Sewanee: The University of the South Belmont University Southern Arkansas University Biola University Southern Methodist University California Baptist University Southwestern Assemblies of God University Centenary College of Louisiana Stephen F. Austin State University Centre College Studio School Los Angeles Christian Brothers University Clemson University Texas Christian University Colorado Christian University Texas Christian University John V. Roach Honors College Colorado School of Mines The American Musical and Dramatic Academy Connecticut College The United States Naval Academy Dallas Baptist University Trevecca Nazarene University Davidson College Trinity University Delta State University Tulane University Ecclesia College University of Alabama Florida State University Full Sail University University of Arkansas Furman University University of Arkansas Honors College Georgetown University University of Arkansas at Little Rock Georgia Institute of Technology University of Arkansas at Monticello Gettysburg College University of Arkansas - Pulaski Technical College Grand Canyon University