Hybridising the Schenkerian Method: a Selected Section of the First Movement of Paul Hindemith’S Piano Sonata No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Advanced Schenkerian Analysis: Perspectives on Phrase Rhythm, Motive, and Form by David Beach

Advanced Schenkerian Analysis: Perspectives on Phrase Rhythm, Motive, and Form by David Beach. New York and London: Routledge, 2012.1 Review by David Carson Berry After Allen Forte’s and Steven Gilbert’s Introduction to Schenkerian Analysis was published in 1982, it effectively had the textbook market to itself for a decade (a much older book by Felix Salzer and a new translation of one by Oswald Jonas not withstanding).2 A relatively compact Guide to Schenkerian Analysis, by David Neumeyer and Susan Tepping, was issued in 1992;3 and in 1998 came Allen Cadwallader and David Gagné’s Analysis of Tonal Music: A Schenkerian Approach, which is today (in its third edition) the dominant text.4 Despite its ascendance, and the firm legacy of the Forte/Gilbert book, authors continue to crowd what is a comparatively small market within music studies. Steven Porter offered the interesting but dubiously named Schenker Made Simple in 1 Advanced Schenkerian Analysis: Perspectives on Phrase Rhythm, Motive, and Form, by David Beach. New York and London: Routledge, 2012; hardback, $150 (978-0- 415-89214-8), paperback, $68.95 (978-0-415-89215-5); xx, 310 pp. 2 Allen Forte and Steven E. Gilbert, Introduction to Schenkerian Analysis (New York: Norton, 1982). Felix Salzer’s book (Structural Hearing: Tonal Coherence in Music [New York: Charles Boni, 1952]), though popular in its time, was viewed askance by orthodox Schenkerians due to its alterations of core tenets, and it was growing increasingly out of favor with mainstream theorists by the 1980s (as evidenced by the well-known rebuttal of its techniques in Joseph N. -

Burn Approved Final Document (With JB Edits)

The German Romantic Style of Paul Hindemith's Piano Sonata no. 1 "Der Main" Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Burn, Douglas-Jayd Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 11/10/2021 10:14:24 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/631332 1 THE GERMAN ROMANTIC STYLE OF PAUL HINDEMITH’S PIANO SONATA NO. 1 “DER MAIN” by Douglas-Jayd Burn __________________________ Copyright © Douglas-Jayd Burn 2018 A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the FRED FOX SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2018 3 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This document has been submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this document are allowable without special permission, provided that an accurate acknowledgement of the source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the copyright holder. SIGNED: Douglas-Jayd Burn 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A document like this takes a village to prepare and it is not possible to thank everyone who has been a part of the process, but I would like to express my thanks to the following: I am sincerely grateful to my major professor Dr. -

Wandlungen in Paul Hindemiths Bach-Verständnis Welches

BACH-BILDER IM 20. JAHRHUNDERT Hermann Danuser: DER KLASSIKER ALS JANUS? Wandlungen in Paul Hindemiths Bach-Verständnis Welches theoretische Modell man auch immer für den Gegenstand einer "Wirkungs-" oder "Rezeptionsgeschichte" bevorzugt - man kann, um grob zu kontrastieren, entweder von der Vielgestaltigkeit eines OEuvres ausgehen, dessen geistig-künstlerische Potenz auf Zeit- genossenschaft und Nachwelt "wirkt", oder aber von der Mannigfaltigkeit der Konkreti- sierungen, in denen Mit- und Nachwelt ein OEuvre "rezipiert" - , in jedem Fall darf man dem \~erk Johann Sebastian Bachs seit dem 19. Jahrhundert den Status der Klassizität beimessen, später gar - so meine ich - den einer Universalität, die von der Musik keines anderen Komponisten übertroffen oder auch nur erreicht worden ist. Dies gilt auch für die erste Hälfte des 20. Jahrhunderts, in kompositionsgeschichtlicher Hinsicht für diesen Zeitraum sogar ganz besonders, überdauerte doch Bach als einziger Klassiker die musikhistorische Epochenzäsur um 1920 in ungeschmälertem Maße, indem er für Roman- tik und Moderne vor dem Ersten Weltkrieg ebenso wie danach für beide Richtungen des Neoklassizismus, für die neotonale Strawinskys und Hindemiths nicht minder als für die dodekaphone der Schönberg-Schule, von freilich verschiedenartiger, stets wieder erneu- erter Bedeutung war und blieb. Solch dauerhafte Geltung aber ist undenkbar ohne tief- greifendste Wandlungen in den Rezeptionsaspekten der Bachsehen Musik. Wer sich nun das Bach-Bild Paul Hindemiths vergegenwärtigt, wird wohl zuerst an -

Computational Methods for Tonality-Based Style Analysis of Classical Music Audio Recordings

Fakult¨at fur¨ Elektrotechnik und Informationstechnik Computational Methods for Tonality-Based Style Analysis of Classical Music Audio Recordings Christof Weiß geboren am 16.07.1986 in Regensburg Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktoringenieur (Dr.-Ing.) Angefertigt im: Fachgebiet Elektronische Medientechnik Institut fur¨ Medientechnik Fakult¨at fur¨ Elektrotechnik und Informationstechnik Gutachter: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Dr. rer. nat. h. c. mult. Karlheinz Brandenburg Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Meinard Muller¨ Prof. Dr. phil. Wolfgang Auhagen Tag der Einreichung: 25.11.2016 Tag der wissenschaftlichen Aussprache: 03.04.2017 urn:nbn:de:gbv:ilm1-2017000293 iii Acknowledgements This thesis could not exist without the help of many people. I am very grateful to everybody who supported me during the work on my PhD. First of all, I want to thank Prof. Karlheinz Brandenburg for supervising my thesis but also, for the opportunity to work within a great team and a nice working enviroment at Fraunhofer IDMT in Ilmenau. I also want to mention my colleagues of the Metadata department for having such a friendly atmosphere including motivating scientific discussions, musical activity, and more. In particular, I want to thank all members of the Semantic Music Technologies group for the nice group climate and for helping with many things in research and beyond. Especially|thank you Alex, Ronny, Christian, Uwe, Estefan´ıa, Patrick, Daniel, Ania, Christian, Anna, Sascha, and Jakob for not only having a prolific working time in Ilmenau but also making friends there. Furthermore, I want to thank several students at TU Ilmenau who worked with me on my topic. Special thanks go to Prof. -

Schenkerian Analysis in the Modern Context of the Musical Analysis

Mathematics and Computers in Biology, Business and Acoustics THE SCHENKERIAN ANALYSIS IN THE MODERN CONTEXT OF THE MUSICAL ANALYSIS ANCA PREDA, PETRUTA-MARIA COROIU Faculty of Music Transilvania University of Brasov 9 Eroilor Blvd ROMANIA [email protected], [email protected] Abstract: - Music analysis represents the most useful way of exploration and innovation of musical interpretations. Performers who use music analysis efficiently will find it a valuable method for finding the kind of musical richness they desire in their interpretations. The use of Schenkerian analysis in performance offers a rational basis and an unique way of interpreting music in performance. Key-Words: - Schenkerian analysis, structural hearing, prolongation, progression,modernity. 1 Introduction Even in a simple piece of piano music, the ear Musical analysis is a musicological approach in hears a vast number of notes, many of them played order to determine the structural components of a simultaneously. The situation is similar to that found musical text, the technical development of the in language. Although music is quite different to discourse, the morphological descriptions and the spoken language, most listeners will still group the understanding of the meaning of the work. Analysis different sounds they hear into motifs, phrases and has complete autonomy in the context of the even longer sections. musicological disciplines as the music philosophy, Schenker was not afraid to criticize what he saw the musical aesthetics, the compositional technique, as a general lack of theoretical and practical the music history and the musical criticism. understanding amongst musicians. As a dedicated performer, composer, teacher and editor of music himself, he believed that the professional practice of 2 Problem Formulation all these activities suffered from serious misunderstandings of how tonal music works. -

PAUL HINDEMITH (1895-1963) in the Later Years of His Life Paul Hindemith Had Become a Somewhat Neglected Figure

TEMPO A QUARTERLY REVIEW OF MODERN MUSIC Edited by Colin Mason © 1964 by Boosey & Hawkes Music Publishers Ltd. PAUL HINDEMITH (1895-1963) In the later years of his life Paul Hindemith had become a somewhat neglected figure. Once ranked with Stravinsky and Bartok among the most stimulating experimenters of the 1920s, he later began to lose his hold on the public, and his influence on younger composers declined, especially after 1945, when serialism started to spread widely, leaving him very much isolated in his hostility to it. Now that that issue no longer greatly agitates the musical world, it is becom- ing possible to assess more clearly the importance and individuality of his con- tribution to 20th-century music. An obvious comparison is with his compatriot of a generation earlier, Max Reger, who was similarly prolific, and in his early days was reckoned daring, but whose work later revealed an academic streak. In Hindemith one might call it rather an intellectual, rational and philosophical streak, not fatal but injurious to the spontaneous play of his musical imagination. As early as 193 1 he wrote an oratorio Das Unaufhorliche, to a text by Gottfried Benn which mocks at human illusions of what is enduring, including (besides learning, science, religion and love) art. Hindemith's choice of such a subject seems to have been symptomatic of some scepticism on his own part about art, and although his innate creative musical genius could not be repressed, it was made to struggle for survival against the theoretical restraints that he insisted on imposing upon it. -

University of Oklahoma

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE THE PIANO CONCERTOS OF PAUL HINDEMITH A DOCUMENT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts By YANG-MING SUN Norman, Oklahoma 2007 UMI Number: 3263429 UMI Microform 3263429 Copyright 2007 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 THE PIANO CONCERTOS OF PAUL HINDEMITH A DOCUMENT APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF MUSIC BY Dr. Edward Gates, chair Dr. Jane Magrath Dr. Eugene Enrico Dr. Sarah Reichardt Dr. Fred Lee © Copyright by YANG-MING SUN 2007 All Rights Reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This paper is dedicated to my beloved parents and my brother for their endless love and support throughout the years it took me to complete this degree. Without their financial sacrifice and constant encouragement, my desire for further musical education would have been impossible to be fulfilled. I wish also to express gratitude and sincere appreciation to my advisor, Dr. Edward Gates, for his constructive guidance and constant support during the writing of this project. Appreciation is extended to my committee members, Professors Jane Magrath, Eugene Enrico, Sarah Reichardt and Fred Lee, for their time and contributions to this document. Without the participation of the writing consultant, this study would not have been possible. I am grateful to Ms. Anna Holloway for her expertise and gracious assistance. Finally I would like to thank several individuals for their wonderful friendships and hospitalities. -

Senior Recital: Xu Xiao, Viola

Senior Recital: Xu Xiao, Viola 20th April, Friday, 6pm, Conservatory Concert Hall _______________________________________________________ JOHANNES BRAHMS (1833-1897) Brahms' Sonata For cello and piano No. 1 in E minor, Op. 38 ( Viola Transcription) l. Allegro non troppo ll. Allegretto quasi Minuetto lll. Allegro INTERMISSION (10’) PAUL HINDEMITH (1895-1963) Der Schwanendreher l. "Zwischen Berg und tiefem Tal" ll. "Nun laube, Lindlein, laube!“ lll. “Seid ihr nicht der schwanendreher” Program Notes: Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Brahms' Sonata No. 1 in E minor, Op. 38 is the first of two sonatas for piano and cello. It was begun in 1862 during Brahms' stay in the mountain village of Bad Munster am Stein-Ebernburg, where he wrote the first two movements and an Adagio movement, which was later dropped. After the existing finale was added in 1865, Brahms dedicated the completed sonata to his friend Josef Gansbacher, an amateur cellist and professor at the Singing Akademie in Vienna. The deep sonorities and the haunting melodies of the Allegro non troppo create a mood throughout the movement that is melancholic and sometimes wistful. The opening theme is a beautiful melody which rises from the depths of the cello's low E, soars for a few moments, then wanders its way back down the G and C strings to give way to the piano entrance. Brahms uses chromaticism to charm in the Allegretto quasi Minuetto. Chromatic melodies in F-sharp minor and A major sweep through the cello line, creating appropriately edgy dissonances on the strong beats of the measure. Sighing figures played three times in succession make up the only asymmetrical phrases in the entire piece. -

Chicago Symphony Orchestra Riccardo Muti Zell Music Director Yo-Yo Ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant

PROGRAM ONE HUNDRED TWENTY-SIXTH SEASON Chicago Symphony Orchestra Riccardo Muti Zell Music Director Yo-Yo Ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Friday, October 14, 2016, at 8:00 Tuesday, October 18, 2016, at 7:30 Riccardo Muti Conductor John Sharp Cello Dvořák Husitská Overture, Op. 67 Schumann Cello Concerto in A Minor, Op. 129 Not too fast— Slow— Very lively JOHN SHARP INTERMISSION Hindemith Concert Music for String Orchestra and Brass, Op. 50 Part 1: Moderately fast and with power—Very broad, but always flowing Part 2: Lively—Slow—Lively Mussorgsky, orch. Ravel Pictures from an Exhibition Promenade 1. Gnomus Promenade— 2. The Old Castle Promenade— 3. Tuileries 4. Bydlo Promenade— 5. Ballet of the Chicks in their Shells 6. Samuel Goldenberg and Schmuyle 7. The Market Place at Limoges 8. Catacombs: Sepulcrum romanum— Promenade: Con mortuis in lingua mortua 9. The Hut on Hen’s Legs (Baba-Yaga)— 10. The Great Gate of Kiev This evening’s performance is generously sponsored by Margot and Josef Lakonishok. CSO Tuesday series concerts are sponsored by United Airlines. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra is grateful to WBBM Newsradio 780 and 105.9 FM for their generous support as media sponsors of the Tuesday series. This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts. COMMENTS by Phillip Huscher Antonín Dvořák Born September 8, 1841; Mühlhausen, Bohemia (now Nelahozeves, Czech Republic) Died May 1, 1904; Prague, Bohemia Husitská Overture, Op. 67 This triumphant music located in the heart of what is today Pilsen, was closed the first concert later established in honor of his visit.) During ever given by the Chicago the exposition, Thomas arranged to send a string Orchestra, on October 16, quartet to the composer’s hotel to read through a 1891. -

School Ofmusic

SHEPHERD SCHOOL CHAMBER ORCHESTRA r LARRY RACHLEFF, music director JAMES DUNHAM, viola Saturday, September 27, 2003 8:00 p.m. Stude Concert Hall RICE UNNERSITY School~ ofMusic f PROGRAM .. • • Suite No. 2 for Small Orchestra Igor Stravinsky y , Marche (1882-1971) Valse Polka Galop Der Schwanendreher Paul Hindemith Zwischen Berg und tiefem Tal. (1895-1963) Langsam - Maf]ig bewegt, mit Kraft Nun laube, Lindlein, laube. Sehr ruhig - Fugato Variationen: Seid ihr nicht der Schwanendreher? Maf]ig schnell James Dunham, soloist ... INTERMISSION Symphony No.] in C Major, Op. 21 Ludwig van Beethoven Adagio molto - Allegro con brio (1770-1827) ,. Andante cantabile con moto Menuetto. Allegro molto e vivace Finale. Allegro molto e vivace The reverberative acoustics of Stude Concert Hall magnify the slightest sound made by the audience. Your care and courtesy will be appreciated. The taking ofphotographs and use of recording equipment are prohibited. SHEPHERD SCHOOL CHAMBER ORCHESTRA Violin I Double Bass (cont.) Trumpet r Maureen Nelson, Andrew Stalker Ryan Gardner concertmaster Carl Lindquist i Brittany Boulding Flute James McClarty Jacqueline Metz Michael Gordon Christopher Scanlon Eden MacAdam-Somer Andrea Kaplan Zebediah Upton Tereza Stanis/av Elizabeth Landon Virginie Gagne Trombone Piccolo Michael Clayville Violin lI Michael Gordon Steven Parker , Martin Shultz, Andrea Kaplan l principal Tuba Maria Evola Oboe Aubrey Ferguson • Angela Millner Erik Behr Jeremy Blanden Nicholas Masterson Harp Turi Hoiseth Sheila McNally Megan Levin Nilvfei Sonja -

Repertoire List

APPROVED REPERTOIRE FOR 2022 COMPETITION: Please choose your repertoire from the approved selections below. Repertoire substitution requests will be considered by the Charlotte Symphony on an individual case-by-case basis. The deadline for all repertoire approvals is September 15, 2021. Please email [email protected] with any questions. VIOLIN VIOLINCELLO J.S. BACH Violin Concerto No. 1 in A Minor BOCCHERINI All cello concerti Violin Concerto No. 2 in E Major DVORAK Cello Concerto in B Minor BEETHOVEN Romance No. 1 in G Major Romance No. 2 in F Major HAYDN Cello Concerto No. 1 in C Major Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Major BRUCH Violin Concerto No. 1 in G Minor LALO Cello Concerto in D Minor HAYDN Violin Concerto in C Major Violin Concerto in G Major SAINT-SAENS Cello Concerto No. 1 in A Minor Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Minor LALO Symphonie Espagnole for Violin SCHUMANN Cello Concerto in A Minor MENDELSSOHN Violin Concerto in E Minor DOUBLE BASS MONTI Czárdás BOTTESINI Double Bass Concerto No. 2in B Minor MOZART Violin Concerti Nos. 1 – 5 DITTERSDORF Double Bass Concerto in E Major PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 2 in G Minor DRAGONETTI All double bass concerti SAINT-SAENS Introduction & Rondo Capriccioso KOUSSEVITSKY Double Bass Concerto in F# Minor Violin Concerto No. 3 in B Minor HARP SCHUBERT Rondo in A Major for Violin and Strings DEBUSSY Danses Sacrée et Profane (in entirety) SIBELIUS Violin Concerto in D Minor DITTERSDORF Harp Concerto in A Major VIVALDI The Four Seasons HANDEL Harp Concerto in Bb Major, Op. -

Program and Abstracts for 2005 Meeting

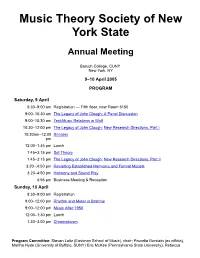

Music Theory Society of New York State Annual Meeting Baruch College, CUNY New York, NY 9–10 April 2005 PROGRAM Saturday, 9 April 8:30–9:00 am Registration — Fifth floor, near Room 5150 9:00–10:30 am The Legacy of John Clough: A Panel Discussion 9:00–10:30 am TextMusic Relations in Wolf 10:30–12:00 pm The Legacy of John Clough: New Research Directions, Part I 10:30am–12:00 Scriabin pm 12:00–1:45 pm Lunch 1:45–3:15 pm Set Theory 1:45–3:15 pm The Legacy of John Clough: New Research Directions, Part II 3:20–;4:50 pm Revisiting Established Harmonic and Formal Models 3:20–4:50 pm Harmony and Sound Play 4:55 pm Business Meeting & Reception Sunday, 10 April 8:30–9:00 am Registration 9:00–12:00 pm Rhythm and Meter in Brahms 9:00–12:00 pm Music After 1950 12:00–1:30 pm Lunch 1:30–3:00 pm Chromaticism Program Committee: Steven Laitz (Eastman School of Music), chair; Poundie Burstein (ex officio), Martha Hyde (University of Buffalo, SUNY) Eric McKee (Pennsylvania State University); Rebecca Jemian (Ithaca College), and Alexandra Vojcic (Juilliard). MTSNYS Home Page | Conference Information Saturday, 9:00–10:30 am The Legacy of John Clough: A Panel Discussion Chair: Norman Carey (Eastman School of Music) Jack Douthett (University at Buffalo, SUNY) Nora Engebretsen (Bowling Green State University) Jonathan Kochavi (Swarthmore, PA) Norman Carey (Eastman School of Music) John Clough was a pioneer in the field of scale theory.