Evening Grosbeak

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wildlife Habitat Plan

WILDLIFE HABITAT PLAN City of Novi, Michigan A QUALITY OF LIFE FOR THE 21ST CENTURY WILDLIFE HABITAT PLAN City of Novi, Michigan A QUALIlY OF LIFE FOR THE 21ST CENTURY JUNE 1993 Prepared By: Wildlife Management Services Brandon M. Rogers and Associates, P.C. JCK & Associates, Inc. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS City Council Matthew C. Ouinn, Mayor Hugh C. Crawford, Mayor ProTem Nancy C. Cassis Carol A. Mason Tim Pope Robert D. Schmid Joseph G. Toth Planning Commission Kathleen S. McLallen, * Chairman John P. Balagna, Vice Chairman lodia Richards, Secretary Richard J. Clark Glen Bonaventura Laura J. lorenzo* Robert Mitzel* Timothy Gilberg Robert Taub City Manager Edward F. Kriewall Director of Planning and Community Development James R. Wahl Planning Consultant Team Wildlife Management Services - 640 Starkweather Plymouth, MI. 48170 Kevin Clark, Urban Wildlife Specialist Adrienne Kral, Wildlife Biologist Ashley long, Field Research Assistant Brandon M. Rogers and Associates, P.C. - 20490 Harper Ave. Harper Woods, MI. 48225 Unda C. lemke, RlA, ASLA JCK & Associates, Inc. - 45650 Grand River Ave. Novi, MI. 48374 Susan Tepatti, Water Resources Specialist * Participated with the Planning Consultant Team in developing the study. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iii PREFACE vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY viii FRAGMENTATION OF NATURAL RESOURCES " ., , 1 Consequences ............................................ .. 1 Effects Of Forest Fragmentation 2 Edges 2 Reduction of habitat 2 SPECIES SAMPLING TECHNIQUES ................................ .. 3 Methodology 3 Survey Targets ............................................ ., 6 Ranking System ., , 7 Core Reserves . .. 7 Wildlife Movement Corridor .............................. .. 9 FIELD SURVEY RESULTS AND RECOMMENDATIONS , 9 Analysis Results ................................ .. 9 Core Reserves . .. 9 Findings and Recommendations , 9 WALLED LAKE CORE RESERVE - DETAILED STUDy.... .. .... .. .... .. 19 Results and Recommendations ............................... .. 21 GUIDELINES TO ECOLOGICAL LANDSCAPE PLANNING AND WILDLIFE CONSERVATION. -

Vertebrate Diversity Benefiting from Carrion Provided by Pumas And

Biological Conservation 215 (2017) 123–131 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Biological Conservation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/biocon Short communication Vertebrate diversity benefiting from carrion provided by pumas and other subordinate, apex felids MARK L. Mark Elbroch⁎, Connor O'Malley, Michelle Peziol, Howard B. Quigley Panthera, 8 West 40th Street, 18th Floor, New York, NY 10018, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Carrion promotes biodiversity and ecosystem stability, and large carnivores provide this resource throughout the Biodiversity year. In particular, apex felids subordinate to other carnivores contribute more carrion to ecological commu- Carnivores nities than other predators. We measured vertebrate scavenger diversity at puma (Puma concolor) kills in the Food webs Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, and utilized a model-comparison approach to determine what variables influ- Scavenging enced scavenger diversity (Shannon's H) at carcasses. We documented the highest vertebrate scavenger diversity of any study to date (39 birds and mammals). Scavengers represented 10.9% of local birds and 28.3% of local mammals, emphasizing the diversity of food-web vectors supported by pumas, and the positive contributions of pumas and potentially other subordinate, apex felids to ecological stability. Scavenger diversity at carcasses was most influenced by the length of time the carcass was sampled, and the biological variables, temperature and prey weight. Nevertheless, diversity was relatively consistent across carcasses. We also identified six additional stalk- and-ambush carnivores weighing > 20 kg, that feed on prey larger than themselves, and are subordinate to other predators. Together with pumas, these seven felids may provide distinctive ecological functions through their disproportionate production of carrion and subsequent contributions to biodiversity. -

Mt. Tabor Park Bird List

Species s S F W Species s S F W Jays & Crows Warblers (continued) *Steller’s Jay c c c f Blackpoll Warbler x *Western Scrub-Jay c c c c MacGillivray’s Warbler u o Mt. Tabor Park *American Crow c c c c *Wilson’s Warbler c o c Swallows Hooded Warbler x Tree Swallow r r Tanagers Bird List Violet-green Swallow f f f *Western Tanager c u u x Northern Rough-winged Swallow x Summer Tanager x Cliff Swallow r r Sparrows *Barn Swallow c c c *Spotted Towhee c c c u Purple Martin x x Chipping Sparrow o r Chickadees Savannah Sparrow x *Black-capped Chickadee c c c c Fox Sparrow f f f *Chestnut-backed Chickadee c c c c *Song Sparrow c c c c Bushtits Lincoln’s Sparrow o r *Bushtit c c c c White-throated Sparrow r r r Nuthatches *White-crowned Sparrow u o u r *Red-breasted Nuthatch c c c c Golden-crowned Sparrow f f f Creepers *Dark-eyed Junco c c c c *Brown Creeper c c c c Grosbeaks Wrens *Black-headed Grosbeak f f f *Bewick’s Wren c c c c Rose-breasted Grosbeak x House Wren x x Buntings *Winter Wren c o c c Lazuli Bunting r x Kinglets Blackbirds Golden-crowned Kinglet c u c c Brewer’s Blackbird x x x x Ruby-crowned Kinglet c c c Red-winged Blackbird x x Thrushes Brown-headed Cowbird f f u Townsend’s Solitaire u r r Orioles Portland, OR Swainson’s Thrush c o c Bullock’s Oriole r x Hermit Thrush c c f Finches *American Robin c c c c Purple Finch f u r Varied Thrush c c c *House Finch c c c c Starlings Red Crossbill u o o o Illustrated and compiled by European Starling f f f f *Pine Siskin f u f f Adrian Hinkle Waxwings *Lesser Goldfinch c c c u January -

Pre-Lesson Plan

Pre-Lesson Plan Prior to taking part in the Winged Migration program at Tommy Thompson Park it is recommended that you complete the following lessons to familiarize your students with some of the birds they might see and some of the concepts they will learn during their field trip. The lessons can easily be integrated into your Science, Language Arts, Social Studies and Physical Education programs. Part 1: Amazing Birds As a class, read the provided “Wanted” posters. The posters depict a very small sampling of some of the amazing feats and features of birds. To complement these readings, display the following websites so that students can see some of these birds “up close.” Common Loon http://www.schollphoto.com/gallery/thumbnails.php?album=1 Black-Capped Chickadee http://sdakotabirds.com/species_photos/black_capped_chickadee.htm Ruby-Throated Hummingbird http://www.surfbirds.com/cgi-bin/gallery/search2.cgi?species=Ruby- throated%20Hummingbird Downy Woodpecker http://www.pbase.com/billko/downy_woodpecker Great Horned Owl www.owling.com/Great_Horned.htm When you visit Tommy Thompson Park, you may see chickadees, hummingbirds, and woodpeckers. These birds all breed in southern Ontario. However, you probably will not see a Great Horned Owl, because this specific bird is usually flying around at night. Below is a list of some other birds students might see when they visit Tommy Thompson Park. Have them chose one bird each and write a “Wanted” poster for it, focusing on a cool fact about that bird. Some web sites that will help them get started -

Are Pine Grosbeaks Increasing at Bird Feeders in Ontario?

87 next month, then less frequently, certainly possible there were other but in larger numbers (up to 30), visits that went unrecorded. for another month. In that time, Bill Walker my notes mention visits to the Deep River, Ontario feeder only four times, the first on 31 January (two birds), but it is Are Pine Grosbeaks Increasing at Bird Feeders in Ontario? by Erica H. Dunn A suggestion has been made that Methods Pine Grosbeaks (Pinicola enucleatm-) OBFS counts were obtained from may now be using bird feeders to a the organizing body, the Long greater degree than in the past Point Bird Observatory. Each year, (Pittaway 1989). Most of the 400-500 people across the province supporting observations, however, tallied the birds observed at their were from a restricted area between feeders during a one to two day Lake Simcoe and Algonquin Park. period, every second week from Here I look at the entire province, November to April. Observers for the period 1976-88, using data recorded the peak count ofeach from Christmas Bird Counts species seen in the observation (CBCs) and the Ontario Bird period. For further details, see Feeder Survey (OBFS). These Dunn (1986). resources allow us to say whether OBFS counts and CBCs were Pine Grosbeaks are now attending divided into three regions: feeders in greater numbers relative Southern Ontario extended to their abundance in the wild (as roughly to a line through Lake measured by CBCs) , as well as to Simcoe to Belleville, including the comment on the hypotheses Bruce Peninsula, Barrie and proposed by Pittaway to explain his Peterborough. -

2020 National Bird List

2020 NATIONAL BIRD LIST See General Rules, Eye Protection & other Policies on www.soinc.org as they apply to every event. Kingdom – ANIMALIA Great Blue Heron Ardea herodias ORDER: Charadriiformes Phylum – CHORDATA Snowy Egret Egretta thula Lapwings and Plovers (Charadriidae) Green Heron American Golden-Plover Subphylum – VERTEBRATA Black-crowned Night-heron Killdeer Charadrius vociferus Class - AVES Ibises and Spoonbills Oystercatchers (Haematopodidae) Family Group (Family Name) (Threskiornithidae) American Oystercatcher Common Name [Scientifc name Roseate Spoonbill Platalea ajaja Stilts and Avocets (Recurvirostridae) is in italics] Black-necked Stilt ORDER: Anseriformes ORDER: Suliformes American Avocet Recurvirostra Ducks, Geese, and Swans (Anatidae) Cormorants (Phalacrocoracidae) americana Black-bellied Whistling-duck Double-crested Cormorant Sandpipers, Phalaropes, and Allies Snow Goose Phalacrocorax auritus (Scolopacidae) Canada Goose Branta canadensis Darters (Anhingidae) Spotted Sandpiper Trumpeter Swan Anhinga Anhinga anhinga Ruddy Turnstone Wood Duck Aix sponsa Frigatebirds (Fregatidae) Dunlin Calidris alpina Mallard Anas platyrhynchos Magnifcent Frigatebird Wilson’s Snipe Northern Shoveler American Woodcock Scolopax minor Green-winged Teal ORDER: Ciconiiformes Gulls, Terns, and Skimmers (Laridae) Canvasback Deep-water Waders (Ciconiidae) Laughing Gull Hooded Merganser Wood Stork Ring-billed Gull Herring Gull Larus argentatus ORDER: Galliformes ORDER: Falconiformes Least Tern Sternula antillarum Partridges, Grouse, Turkeys, and -

1 CWU Comparative Osteology Collection, List of Specimens

CWU Comparative Osteology Collection, List of Specimens List updated November 2019 0-CWU-Collection-List.docx Specimens collected primarily from North American mid-continent and coastal Alaska for zooarchaeological research and teaching purposes. Curated at the Zooarchaeology Laboratory, Department of Anthropology, Central Washington University, under the direction of Dr. Pat Lubinski, [email protected]. Facility is located in Dean Hall Room 222 at CWU’s campus in Ellensburg, Washington. Numbers on right margin provide a count of complete or near-complete specimens in the collection. Specimens on loan from other institutions are not listed. There may also be a listing of mount (commercially mounted articulated skeletons), part (partial skeletons), skull (skulls), or * (in freezer but not yet processed). Vertebrate specimens in taxonomic order, then invertebrates. Taxonomy follows the Integrated Taxonomic Information System online (www.itis.gov) as of June 2016 unless otherwise noted. VERTEBRATES: Phylum Chordata, Class Petromyzontida (lampreys) Order Petromyzontiformes Family Petromyzontidae: Pacific lamprey ............................................................. Entosphenus tridentatus.................................... 1 Phylum Chordata, Class Chondrichthyes (cartilaginous fishes) unidentified shark teeth ........................................................ ........................................................................... 3 Order Squaliformes Family Squalidae Spiny dogfish ........................................................ -

2020 Indiana Bird List

2020 INDIANA BIRD LIST Kingdom – ANIMALIA ORDER: Cathartiformes Larks (Alaudidae) New World Vultures (Cathartidae) Horned Lark Phylum – CHORDATA Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura Subphylum – VERTEBRATA ORDER: Gruiformes Swallows (Hirundinidae) Class - AVES Rails, Gallinules, and Coots (Rallidae) Purple Martin Family Group (Family Name) American Coot Barn Swallow Hirundo rustica Common Name [Scientific name Chickadees and Titmice (Paridae) is in italics] ORDER: Charadriiformes Tufted Titmouse Baeolophus bicolor ORDER: Anseriformes Lapwings and Plovers (Charadriidae) Nuthatches (Sittidae) Ducks, Geese, and Swans (Anatidae) Killdeer Charadrius vociferus Red-breasted Nuthatch Sitta canadensis Snow Goose Sandpipers, Phalaropes, and Allies Wrens (Troglodytidae) Canada Goose Branta canadensis (Scolopacidae) Wood Duck Aix sponsa Carolina Wren Spotted Sandpiper Kinglets (Regulidae) Mallard Anas platyrhynchos Gulls, Terns, and Skimmers (Laridae) Golden-crowned Kinglet Ring-billed Gull Ruby-crowned Kinglet ORDER: Galliformes Herring Gull Larus argentatus Partridges, Grouse, Turkeys, and Old Thrushes (Turdidae) Eastern Bluebird World Quail (Phasianidae) ORDER: Columbiformes *Ring-necked Pheasant Pigeons and Doves (Columbidae) American Robin Turdus migratorius Mockingbirds and Thrashers (Mimidae) Ruffed Grouse Bonasa umbellus Mourning Dove Zenaida macroura Wild Turkey Meleagris gallopavo Gray Catbird Northern Mockingbird Mimus polyglottos Northern Bobwhite ORDER: Strigiformes Typical Owls (Strigidae) Brown Thrasher Toxostoma rufum ORDER: Gaviiformes Great -

CANADA: Winter Owls and Boreal Birding Feb-March 2017

Tropical Birding Trip Report CANADA: Winter Owls and Boreal Birding Feb-March 2017 A Tropical Birding custom BIRDING tour CANADA: Winter Owls and Boreal Birding 26th February - 1 st March 2017 We traveled to the outskirts of Montreal to fulfill our principal birding objective, getting great looks at the “Gray Ghost”: Great Gray Owl Tour Leaders: Sam Woods (Report and all photos by Sam Woods) and Tom Hince 1 www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Page Tropical Birding Trip Report CANADA: Winter Owls and Boreal Birding Feb-March 2017 INTRODUCTION This short custom tour was set up at the last minute (in early February), when news came through of fair numbers of Great Gray Owls around at that time in Ontario. The person, for whom this was arranged, had the main objective of finding this so-called “Phantom of the North”. For this tour we were accompanied by Tom Hince, who has many years under his belt chasing owls and boreal birds of all sorts throughout Canada, and so was the perfect companion, with his owl-finding skills and vast network of local connections, ideally suited for us on this “owl quest”. The tour started and ended in Toronto in Ontario, but we also ventured into Ottawa and Montreal too, to allow us to cast a wide net in which to search, where needed. Our Great Gray Owl quest was entirely successful (eventually), with us being able to spend ages staring at this boreal beast, as it sat nonchalantly above us. We had the bird all to ourselves for most of the time, and we didn’t need to use the controversial method of baiting with mice that some others choose to do. -

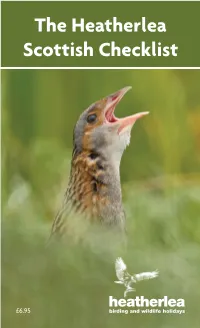

The Heatherlea Scottish Checklist

K_\?\Xk_\ic\X JZfkk`j_:_\Zbc`jk -%0, birding and wildlife holidays K_`j:_\Zbc`jkY\cfe^jkf @]]fle[#gc\Xj\i\kliekf2 * K_\?\Xk_\ic\X JZfkk`j_:_\Zbc`jk ?\Xk_\ic\X`jXn`c[c`]\$nXkZ_`e^_fc`[XpZfdgXep# ]fle[\[`e(00(Xe[YXj\[`eJZfkcXe[XkK_\Dflekm`\n ?fk\c#E\k_p9i`[^\%N\_Xm\\eafp\[j_fn`e^k_\Y`i[c`]\ f]JZfkcXe[kfn\ccfm\ik\ek_fljXe[g\fgc\fe^l`[\[ _fc`[Xpj[li`e^k_\cXjk).j\Xjfej#`ecfZXk`fejk_ifl^_flk k_\dX`ecXe[Xe[dfjkf]k_\XZZ\jj`Yc\`jcXe[j#`eZcl[`e^ k_\@ee\iXe[Flk\i?\Yi`[\jXe[XccZfie\ijf]Fibe\pXe[ J_\kcXe[% N\]\\ck_\i\`jXe\\[]fiXÊJZfkk`j_:_\Zbc`jkË]filj\ `ek_\Ô\c[#Xe[[\Z`[\[kfgif[lZ\k_`jc`kkc\Yffbc\k]fi pflig\ijfeXclj\%@k`jZfej`jk\ekn`k_Yfk_k_\9i`k`j_ Xe[JZfkk`j_9`i[c`jkjXe[ZfekX`ejXcck_fj\jg\Z`\j`e :Xk\^fi`\j8#9Xe[:% N\_fg\k_`jc`kkc\:_\Zbc`jk`jlj\]lckfpfl#Xe[k_Xkpfl \eafpi\nXi[`e^Xe[i\jgfej`Yc\Y`i[nXkZ_`e^`eJZfkcXe[% K_\?\Xk_\ic\XK\Xd heatherlea birding and wildlife holidays + K_\?\Xk_\ic\XJZfkk`j_ Y`i[`e^p\Xi)'(- N_XkXjlg\iYp\Xif]Y`i[`e^n\\eafp\[Xifle[k_\?`^_cXe[j Xe[@jcXe[j?\i\`jXYi`\]\okiXZk]ifdfli9`i[`e^I\gfik% N\jkXik\[`eAXelXipn`k_cfm\cpC`kkc\8lb`e^ff[eldY\ij # Xe[8d\i`ZXeN`^\fe#>cXlZflj>lccXe[@Z\cXe[>lccfek_\ ZfXjkXd`[k_fljXe[jf]nX[\ijXe[n`c[]fnc%=\YilXipXe[ DXiZ_jXnlj_\X[kfk_\efik_[li`e^Ê?`^_cXe[N`ek\i9`i[`e^Ë# ]\Xkli`e^Jlk_\icXe[Xe[:X`k_e\jj%FliiXi`kpÔe[`e^i\Zfi[_\i\ `j\oZ\cc\ek#Xe[`e)'(-n\jXnI`e^$Y`cc\[Xe[9feXgXik\Ëj>lccj% N`k_>i\\e$n`e^\[K\XcjXe[Jd\nZcfj\ikf_fd\n\n\i\ Xci\X[pYl`c[`e^XY`^p\Xic`jkKfnXi[jk_\\e[f]DXiZ_fliki`gj jkXik\[m`j`k`e^k_\N\jk:fXjk#n`k_jlg\iYFkk\iXe[<X^c\m`\nj% K_`jhlfk\jldj`klge`Z\cp1 Ê<m\ipk_`e^XYflkkf[XpnXjYi\Xk_$kXb`e^N\Ôe`j_\[n`k_ -

Learn About Texas Birds Activity Book

Learn about . A Learning and Activity Book Color your own guide to the birds that wing their way across the plains, hills, forests, deserts and mountains of Texas. Text Mark W. Lockwood Conservation Biologist, Natural Resource Program Editorial Direction Georg Zappler Art Director Elena T. Ivy Educational Consultants Juliann Pool Beverly Morrell © 1997 Texas Parks and Wildlife 4200 Smith School Road Austin, Texas 78744 PWD BK P4000-038 10/97 All rights reserved. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means – graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or information storage and retrieval systems – without written permission of the publisher. Another "Learn about Texas" publication from TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE PRESS ISBN- 1-885696-17-5 Key to the Cover 4 8 1 2 5 9 3 6 7 14 16 10 13 20 19 15 11 12 17 18 19 21 24 23 20 22 26 28 31 25 29 27 30 ©TPWPress 1997 1 Great Kiskadee 16 Blue Jay 2 Carolina Wren 17 Pyrrhuloxia 3 Carolina Chickadee 18 Pyrrhuloxia 4 Altamira Oriole 19 Northern Cardinal 5 Black-capped Vireo 20 Ovenbird 6 Black-capped Vireo 21 Brown Thrasher 7Tufted Titmouse 22 Belted Kingfisher 8 Painted Bunting 23 Belted Kingfisher 9 Indigo Bunting 24 Scissor-tailed Flycatcher 10 Green Jay 25 Wood Thrush 11 Green Kingfisher 26 Ruddy Turnstone 12 Green Kingfisher 27 Long-billed Thrasher 13 Vermillion Flycatcher 28 Killdeer 14 Vermillion Flycatcher 29 Olive Sparrow 15 Blue Jay 30 Olive Sparrow 31 Great Horned Owl =female =male Texas Birds More kinds of birds have been found in Texas than any other state in the United States: just over 600 species. -

Sax-Zim Bog and Northeast Minnesota: Jan 17-21, 2019

TRIP LIST: Sax-Zim Bog and Northeast Minnesota with IAS Jan. 17-21, 2019 Sax-Zim Bog and Northeast Minnesota with the Illinois Audubon Society January 17-21, 2019 Tour leaders: Josh Engel and Ethan Kistler Photo gallery: www.redhillbirding.com/minnesota-2019-gallery-1 BIRD LIST. 41 species. Taxonomy follows the Clements/eBird Checklist, 2018 update. Former (or alternate) English names are in parentheses. (H) = heard only. IUCN Red List status is listed for threatened and near-threatened species: CR=Critically Endangered, EN=Endangered, VU=Vulnerable, NT=Near-threatened. Mallard - Anas platyrhynchos American Black Duck - Anas rubripes With a flock of Mallards on the Duluth lakefront right by the hotel. Long-tailed Duck (VU) - Clangula hyemalis A couple of flocks were in the harbor at Two Harbors. Common Goldeneye - Bucephala clangula Common Merganser - Mergus merganser Red-breasted Merganser - Mergus serrator Sharp-tailed Grouse - Tympanuchus phasianellus Great looks at several individuals in Sax-Zim Bog. Wild Turkey - Meleagris gallopavo Rock Pigeon - Columba livia Herring Gull - Larus argentatus Glaucous Gull - Larus hyperboreus Great looks at adults and immatures at the Superior, Wisconsin, dump. Bald Eagle - Haliaeetus leucocephalus Rough-legged Hawk - Buteo lagopus We were happy to find one at the Superior, Wisconsin, airport, given that none were being regularly seen in the area this winter. Snowy Owl (VU) - Bubo scandiacus A snowy white adult male sitting on a hay bale was one of the first birds we saw in Sax-Zim Bog. Northern Hawk Owl - Surnia ulula Our walk over a packed-snow path in sub-zero temperatures was worth it for the great views we got of this rare owl.