Suicide, Concussions, and the NFL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

March Is Brain Injury Awareness Month 2007 Spring TBI & Post Traumatic Stress Disorder Dual-Diagnosis & Treatment

RAINBOW A QUARTERLY NEWS MAGAZINE for Acquired Brain InjuryVISIONS Professionals, Survivors and Families www.rainbowrehab.com RAINBOW REHABILITATION CENTERS, INC. Volume IV No. 2 March is Brain Injury Awareness Month 2007 Spring TBI & Post Traumatic Stress Disorder Dual-Diagnosis & Treatment Interview with Military TBI & PTSD Survivor Charlie Morris Mark Evans & Vicky Scott, NP on Rainbow’s NeuroRehab Campus Helmet Technology Advances–Part 1 | 2007 TBI Conference Dates March2007 is brain injuryAwareness month. What’s News in the Industry which severely shake the brain within the skull, have become the signature injury of Raising Awareness the War in Iraq. These blasts often cause By Bill Buccalo, President devastating brain injuries, and patients may have long-term cognitive, psychological and medical consequences. The most severely injured service members will arch is Brain Injury Awareness York Times article, Dr. Bennet Omalu, a require extensive rehabilitation and lifelong Month. Raising public awareness University of Pittsburgh neuropathologist, personal and clinical support. of the “silent epidemic” of brain injury recently examined the brain tissue of We are concerned about whether the is important in the fight to decrease the former NFL player Andre Waters. Mr. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) can Malarming number of injuries sustained each Waters (44 years old) had committed fully address the needs of our service year; to increase the access to services suicide in November subsequent to men and women on a variety of fronts. for those who have sustained an injury, as a period of depression. The doctor During a September 2006 hearing of the well as to create a more compassionate concluded that Mr. -

Washington Post's Hit-Piece

We are Becoming a Nation of Lies. Dr. Bennet Omalu’s Response to the Washington Post Hit-Piece on January 22, 2020 Page 1 of 6 WE ARE BECOMING A NATION OF LIES. My response to the Washington Post Hit-Piece on January 22, 2020 Bennet Omalu, MD, MBA, MPH, CPE, DABP-AP,CP,FP,NP January 28, 2020 On December 16, 2019, the Washington Post reported that Donald Trump, the President of the United States of America has told over fifteen thousand lies within his first three years in office. It is becoming apparent that as a nation and society we are beginning to conform to a culture of telling lies to attain every objective, and as long as we win or get what we want, it does not matter, since the truth may no longer be that relevant. This emerging culture may pose a greater threat to our society than Russia, China and Iran combined. On January 22, 2020, the same Washington Post did a takedown and hit-piece on me based on lies. I do not understand why a highly respected news organization will allow their international reputation and platform to be used to propagate lies about an American who has sacrificed so much to make a difference in the lives of other Americans. A whole lot has been written and published to establish the truth and facts about my life and work since 2002 including the “League of Denial”, “Concussion” and my memoir “Truth Doesn’t Have a Side”. In fact, a major Hollywood motion picture, “Concussion” was produced by Sony Pictures to document the true story of my life and work. -

Leadership Report

RICHARD J. KATHRINS, Ph.D. President & CEO LEADERSHIP REPORT JANUARY 2016 The movie “Concussion” was released on December 25, providing an important account of the debilitating effects of repeated traumatic brain injury. The movie is based on the compelling, true story of forensic pathologist Dr. Bennet Omalu who conducted an autopsy in 2002 on Mike Webster, a lineman for the Pittsburgh Steelers, after he died unexpectedly. Dr. Omalu, along with Dr. Julian Bales, was the first to diagnose chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), similar to Alzheimer’s Disease, in a professional football player. After publishing his findings in Neurosurgery, Dr. Omalu dedicated himself to raising awareness about the dangers of football-related brain injury. He became an important voice in a subsequent class-action lawsuit against the NFL and was one of the founding members of The Brain Injury Research Institute with a mission to study “the short and long-term impact of brain injury, in general, and specifically in concussions.” As healthcare and rehabilitation professionals, we understand the critical danger and consequences that may be faced by those who experience a traumatic brain injury. The CDC estimates that 1.6-3.8 million sports and recreation-related concussions occur in this country each year. In addition, the CDC reports an estimated 5.3 million Americans live with a traumatic brain injury-related disability. Dr. Omalu’s work portrayed in this major motion picture will shine a much- needed spotlight on the growing incidence of sports-related concussion. The CDC reports that from 2001 to 2009, “the rate of ED visits for sports and recreation injuries with a diagnosis of concussion or TBI, alone or in combination with other injuries, rose 57 percent among children age 19 or younger.” It is crucial that we not only recognize this issue, but that we work to prevent these traumatic brain injuries from occurring. -

The NFL and Its Concussion Crisis: Adapting the Contingency Theory to Examine Shifts in Publics’ Stances

Journal of US-China Public Administration, March 2016, Vol. 13, No. 3, 181-188 doi: 10.17265/1548-6591/2016.03.005 D DAVID PUBLISHING The NFL and Its Concussion Crisis: Adapting the Contingency Theory to Examine Shifts in Publics’ Stances Douglas Wilbur, Dani Myers The University of Missouri-Columbia, Columbia, USA The National Football League (NFL) is immersed in a serious conflict involving a disease called Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE), and conflict appears to have manifested into a crisis with the release of Sony Motion Picture’s film Concussion. This study uses the contingency theory of conflict management, which explains how an organization adopts toward a given public. No research has been done to identify if various unorganized publics can develop stances like an organization. A quantitative content analysis of 1,035 tweets about the movie and the NLF concussion issue was done immediately before and after the movie’s release. Findings revealed some initial evidence that publics can develop a stance. In particular, most of the publics favored the movie and assumed a hostile stance toward the NFL. Only the health community revealed a stance suitable for cooperating with the NFL on the issue. Keywords: crisis communication, contingency theory of conflict management, public relations, sports communication The release of the Sony Motion Picture’s film, Concussion is a crisis tipping point in a serious long-term conflict facing the National Football League (NFL), American football, and the numerous industries it supports. The movie is highly critical of the NFL, highlighting the discovery of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) in deceased NFL players. -

Deprived Her of the Companionship and Society of Her Father, Aaron Hernandez

Case 1:17-cv-11812 Document 1 Filed 09/21/17 Page 1 of 18 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF MASSACHUSETTS AVIELLE HERNANDEZ, by her Guardian,: SHAYANNA JENKINS HERNANDEZ. vs. C.A. NO.: NATIONAL FOOTBALL LEAGUE and. THE NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS, LLC: COMPLAINT AND JURY DEMAND Introduction 1. Avielle Hernandez, by and through her parent and Guardian, Shayanna Jenkins Hernandez ("Plaintiff"), brings this action to seek redress for the loss of parental consortium she has experienced based on the negligent conduct of Defendants that deprived her of the companionship and society of her father, Aaron Hernandez. 2. At the time of his death, Aaron Hernandez ("Aaron") had the most severe case of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy("CTE") medically seen in a person of his young age of 28 years by the world renowned CTE Center at Boston University. Aaron had Stage III CTE usually seen in players with a median age of death of 67 years. Aaron played football in the National Football League ("NFL") for the New England Patriots for three (3) seasons starting in 2010. By the time Aaron entered the NFL, in 2010, Defendants were fully aware of the damage that could be inflicted from repetitive impact injuries and failed to disclose, treat, or protect him from the dangers of such damage. This complaint seeks damages for his young daughter Avielle from Defendants the NFL and the New England Patriots. 1 Case 1:17-cv-11812 Document 1 Filed 09/21/17 Page 2 of 18 Parties 3. Avielle Hernandez is a minor and the daughter of the deceased, Aaron Hernandez. -

A Challenge Against Former Nfl Players’ Future Lawsuits Against the Nfl and Their Former Teams: New Scientific Information and Assumption of Risk

A CHALLENGE AGAINST FORMER NFL PLAYERS’ FUTURE LAWSUITS AGAINST THE NFL AND THEIR FORMER TEAMS: NEW SCIENTIFIC INFORMATION AND ASSUMPTION OF RISK ABSTRACT The National Football League (NFL) is a staple of U.S. culture. Millions of Americans plan their Sundays around watching professional football games. The NFL generates billions of dollars annually from its position as the most popular professional sports league in the United States. For years the NFL sold its fan base on massive hits between players and encouraged violent collisions on the field. As a result, player safety often took a back seat to entertainment. Eventually many former NFL players began to experience major mental health problems later in life due to the massive collisions they experienced when they played in the NFL. Many former players ended up taking their own life as a result. Former players, or the families of deceased former players, finally began suing the NFL as a result of their development of mental health problems, claiming the NFL’s lack of concern for player safety proximately caused their injuries. In 2016, the NFL entered into a massive settlement with a class of former players who suffered serious medical conditions associated with repeated head trauma. Other former NFL players and their families continue to bring suits against the NFL. Until recently there were not many defenses available to the NFL in defending against these suits. This Note proposes the NFL should no longer be held liable for future players’ mental health problems. As a result of recent medical studies concluding NFL players are nearly certain to suffer from mental health problems during their lifetime, the tort doctrine of assumption of risk should apply to negate or, alternatively, severely limit the NFL’s liability in future lawsuits brought by current players after they quit playing. -

(Expert Ties Ex-Player\222S Suicide to Brain Damage

Expert Ties Ex-Player’s Suicide to Brain Damage - New York Times http://www.nytimes.com/2007/01/18/sports/football/18waters.html?ei=5... January 18, 2007 Expert Ties Ex-Player’s Suicide to Brain Damage By ALAN SCHWARZ Since the former National Football League player Andre Waters killed himself in November, an explanation for his suicide has remained a mystery. But after examining remains of Mr. Waters’s brain, a neuropathologist in Pittsburgh is claiming that Mr. Waters had sustained brain damage from playing football and he says that led to his depression and ultimate death. The neuropathologist, Dr. Bennet Omalu of the University of Pittsburgh, a leading expert in forensic pathology, determined that Mr. Waters’s brain tissue had degenerated into that of an 85-year-old man with similar characteristics as those of early-stage Alzheimer’s victims. Dr. Omalu said he believed that the damage was either caused or drastically expedited by successive concussions Mr. Waters, 44, had sustained playing football. In a telephone interview, Dr. Omalu said that brain trauma “is the significant contributory factor” to Mr. Waters’s brain damage, “no matter how you look at it, distort it, bend it. It’s the significant forensic factor given the global scenario.” He added that although he planned further investigation, the depression that family members recalled Mr. Waters exhibiting in his final years was almost certainly exacerbated, if not caused, by the state of his brain — and that if he had lived, within 10 or 15 years “Andre Waters would have been fully incapacitated.” Dr. -

Truthside2 Samptxt.Pdf

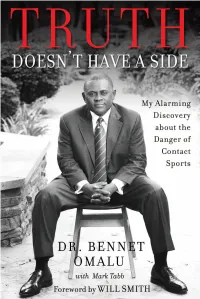

Praise for Truth Doesn’t Have a Side If you want to understand Dr. Bennet Omalu, don’t look at the acronyms that come after his name or read the papers he’s authored; listen to his laugh. It’s the laugh of someone who possesses the freedom that can only come when you know that you are doing exactly what you were destined to do. Will Smith The name Bennet Omalu is one that many people may not be familiar with. But if you are a current or former athlete, a wife or a significant other of an athlete, or a parent of an athlete who competes or has competed in a contact sport that could produce concussions, his is a name you should know. His discovery of CTE gave a name to a cause of a neurological condition that many former athletes suffered from later in life. For many former football players like me, Dr. Omalu is our hero because he was that one person astute and bold enough to dig deeper in his neuropathology research to discover the cause of neurological ailments that may have af- fected countless former athletes long after the cheering stopped. Harry Carson, New York Giants (1976–1988), and a member of the Professional Football Hall of Fame, class of 2006 Truth Doesn’t Have a Side is a critically important book. If you care about your brain or the brains of those you love, please read it. Daniel G. Amen, MD, author of Memory Rescue Dr. Bennet Omalu’s tireless pursuit of the truth is inspiring, and being able to relive his journey alongside him makes it all the more incredible. -

The Concussion Crisis in the National Football League and What Is Being Done to Fix It

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Jessie O'Kelly Freshman Essay Award English 12-1-2019 The Concussion Crisis in the National Football League and What is Being Done to Fix it Bennett Perkins University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/englfea Part of the Neurology Commons Citation Perkins, B. (2019). The Concussion Crisis in the National Football League and What is Being Done to Fix it. Jessie O'Kelly Freshman Essay Award. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.uark.edu/englfea/4 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the English at ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jessie O'Kelly Freshman Essay Award by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running Head: The Concussion Crisis in the National Football League 1 The Concussion Crisis in the National Football League and What is Being Done to Fix it Bennett Perkins University of Arkansas The Concussion Crisis in the National Football League 2 The Concussion Crisis in the National Football League and What is Being Done to Fix it Football has been a popular sport in America since the 1920s. With the sport being so popular, there are many levels ranging from high school to college to various professional leagues. According to Kathryn Heinze and Di Lu (2017), the National Football League, the most popular professional football league, is the biggest and most powerful sports league in the United States. In 2015, the estimated revenue was $13 billion (Heinze & Lu, 2017). -

America Has Voted

November/December 2016 A publication of the U.S. Mission in Nigeria CROSSROADS AMERICA HAS VOTED 1 CROSSROADS | October/November 2016 EVENTS SECRETARY KERRY VISITS ABUJA July 23 & 24, 2016 Secretary Kerry Shakes Hands With Nigerian President Young women in STEM show Secretary Kerry their projects Muhummadu Buhari at the Presidential Villa in Abuja following a meeting at the U.S. Embassy in Abuja Secretary Kerry meets with a group of young women who have Secretary Kerry is made welcome by the Nigerian been empowered, or are empowering others through Education Foreign Affairs Minister, Geoffrey Onyeama Secretary Kerry Addresses staff of the Secretary Kerry Poses for a Photo with the U.S. Marine U.S. Embassy and their family members Security Guard Detachment in Abuja, Nigeria AMBASSADOR’S NOTES delighted to be here and especially new chapters to our long history grateful to have arrived now, with an of working with Nigeria to support opportunity to build on the legacy of democracy, justice, and civil rights, your successes over the past years. health and education, peace and From strengthening the Nigerian security, and economic growth and polity, to stopping Ebola, to fighting development. Our partnership to terror and helping victims, your advance our common interests will response together with your partners continue. has been remarkable. This issue highlights some of the We are deeply grateful to be one activities we are working on with of those partners. I am thankful to Nigerians. For example, the United every Nigerian who has worked to States Agency for International forge between our nations and our Development is engaged in providing peoples enduring ties strengthened humanitarian assistance to families by shared principles and common in the Northeast displaced by the interests. -

© 2021 Reachmd Page 1 of 3 Seeing

Transcriipt Detaiills This is a transcript of an educational program accessible on the ReachMD network. Details about the program and additional media formats for the program are accessible by visiting: https://reachmd.com/programs/clinicians-roundtable/the-autopsy-that-changed- american-sports-dr-bennett-omalu-and-the-story-of-cte/9979/ ReachMD www.reachmd.com [email protected] (866) 423-7849 The Autopsy that Changed American Sports: Dr. Bennett Omalu and the Story of CTE Dr. Johnson: This is a Clinician's Roundtable on ReachMD, and I am Dr. Shira Johnson. With me today is Dr. Bennet Omalu. Dr. Omalu is a forensic pathologist and neuropathologist, and he holds multiple other degrees and board certifications including a Master's of Public Health and Epidemiology - University of Pittsburgh, and an MBA from the Tepper School of Business at Carnegie Mellon UniversityHe was the first to discover and publish findings of CTE, chronic traumatic encephalopathy, in American football players. The book Concussion, which was based on his work, was published in 2015 and later adapted into a film of the same name. Today we're discussing CTE, which has been diagnosed on autopsies that were performed on NFL players as well as other professional athletes. Dr. Omalu, welcome to the program. Dr. Omalu: Thank you so much for having me, Dr. Johnson. I'm glad to be here. Dr. Johnson: There is so much we can talk about, but let's start out by telling us how you were led to your discovery of CTE while performing autopsies? Dr. Omalu: Well, what happened, I was in Pittsburgh 3 months outside my training and fellowship as a neuropathologist, so you may say that I was still very academically hot. -

Cted to Repeated Mild Traumatic Brain Injury

SPECIAL REPORT CHRONIC TRAUMATIC ENCEPHALOPATHY IN A NATIONAL FOOTBALL LEAGUE PLAYER Bennet I. Omalu, M.D., OBJECTIVE: We present the results of the autopsy of a retired professional football M.P.H. player that revealed neuropathological changes consistent with long-term repetitive Departments of Pathology concussive brain injury. This case draws attention to the need for further studies in the and Epidemiology, University of Pittsburgh, cohort of retired National Football League players to elucidate the neuropathological Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania sequelae of repeated mild traumatic brain injury in professional football. METHODS: The patient’s premortem medical history included symptoms of cognitive Steven T. DeKosky, M.D. impairment, a mood disorder, and parkinsonian symptoms. There was no family Departments of Human Genetics history of Alzheimer’s disease or any other head trauma outside football. A complete and Neurology, University of Pittsburgh, autopsy with a comprehensive neuropathological examination was performed on the Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania retired National Football League player approximately 12 years after retirement. He died suddenly as a result of coronary atherosclerotic disease. Studies included deter- Ryan L. Minster, M.S.I.S. mination of apolipoprotein E genotype. Department of Human Genetics, RESULTS: Autopsy confirmed the presence of coronary atherosclerotic disease with University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania dilated cardiomyopathy. The brain demonstrated no cortical atrophy, cortical contu- sion, hemorrhage, or infarcts. The substantia nigra revealed mild pallor with mild M. Ilyas Kamboh, Ph.D. dropout of pigmented neurons. There was mild neuronal dropout in the frontal, Department of Human Genetics, parietal, and temporal neocortex. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy was evident with University of Pittsburgh, many diffuse amyloid plaques as well as sparse neurofibrillary tangles and -positive Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania neuritic threads in neocortical areas.