JAN-JUL 1998 Number 25 Pachyderm S P E C I E S S U R V I V a L JAN- JUL 1998 Number 25 C O M M I S S I O N Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cameroon Humanitarian Situation Report

SITUATION REPORT MAY-JUNE 2016 Cameroon Humanitarian Situation Report SITUATION IN NUMBERS Highlights 30 June 2016 Cameroon has the highest number of internally displaced persons 194,517 MALNOURISHED CHILDREN and refugees as part of the sub-regional crisis as a result of the 61,262 with Severe Acute Malnutrition ongoing conflict with Boko Haram, following Nigeria. 133,255 with Moderate Acute Malnutrition Since the beginning of 2016, 23,150 children under 5 (including (UNICEF-MOH, SMART 2015) 2,669 refugee children) have been admitted for therapeutic care for severe acute malnutrition (SAM) 259,145 CAR REFUGEES (UNHCR, April 2016) 702 children unaccompanied and separated as a result of the CAR refugee crisis and the Nigeria crisis have been either placed in 64,938 NIGERIAN REFUGEES interim care and/or are receiving appropriate follow-up through 56,830 in the Minawao refugee camp UNICEF support. 3,829 arrived since January 2016 (UNHCR, May 2016) The funding situation remains worrisome which are constraining 116,200 children out of lifesaving activities. Child protection, education, HIV and health remain the most underfunded sectors. UNICEF’s Humanitarian 190,591 INTERNALLY DISPLACED response funding gap is at 83%. PERSONS 83% of displacements caused by the conflict (IOM, DTM April 2016) US$ 31.4 million REQUIRED UNICEF’s Response with partners UNICEF Sector/Cluster 17% funding available in 2016 2016 2016 Cumulative Cumulative UNICEF Cluster 12,000,000 results (#) results (#) Target Target 10,000,000 Number of CAR refugee children 39,000 -

The Status of Kenya's Elephants

The status of Kenya’s elephants 1990–2002 C. Thouless, J. King, P. Omondi, P. Kahumbu, I. Douglas-Hamilton The status of Kenya’s elephants 1990–2002 © 2008 Save the Elephants Save the Elephants PO Box 54667 – 00200 Nairobi, Kenya first published 2008 edited by Helen van Houten and Dali Mwagore maps by Clair Geddes Mathews and Philip Miyare layout by Support to Development Communication CONTENTS Acknowledgements iv Abbreviations iv Executive summary v Map of Kenya viii 1. Introduction 1 2. Survey techniques 4 3. Data collection for this report 7 4. Tsavo 10 5. Amboseli 17 6. Mara 22 7. Laikipia–Samburu 28 8. Meru 36 9. Mwea 41 10. Mt Kenya (including Imenti Forest) 42 11. Aberdares 47 12. Mau 51 13. Mt Elgon 52 14. Marsabit 54 15. Nasolot–South Turkana–Rimoi–Kamnarok 58 16. Shimba Hills 62 17. Kilifi District (including Arabuko-Sokoke) 67 18. Northern (Wajir, Moyale, Mandera) 70 19. Eastern (Lamu, Garissa, Tana River) 72 20. North-western (around Lokichokio) 74 Bibliography 75 Annexes 83 The status of Kenya’s elephants 1990–2002 AcKnowledgemenTs This report is the product of collaboration between Save the Elephants and Kenya Wildlife Service. We are grateful to the directors of KWS in 2002, Nehemiah Rotich and Joseph Kioko, and the deputy director of security at that time, Abdul Bashir, for their support. Many people have contributed to this report and we are extremely grateful to them for their input. In particular we would like to thank KWS field personnel, too numerous to mention by name, who facilitated our access to field records and provided vital information and insight into the status of elephants in their respective areas. -

Cameroon | Displacement Report, Far North Region Round 9 | 26 June – 7 July 2017 Cameroon | Displacement Report, Far North Region, Round 9 │ 26 June — 7 July 2017

Cameroon | Displacement Report, Far North Region Round 9 | 26 June – 7 July 2017 Cameroon | Displacement Report, Far North Region, Round 9 │ 26 June — 7 July 2017 The opinions expressed in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries.1 IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergovernmental organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to: assist in meeting the operational challenges of migration; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. International Organization for Migration UN House Comice Maroua Far North Region Cameroon Cecilia Mann Tel.: +237 691 794 050 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.globaldtm.info/cameroon/ © IOM 2017 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. 1 The maps included in this report are illustrative. The representations and the use of borders and geographic names may include errors and do not imply judgment on legal status of territories nor acknowledgement of borders by the Organization. -

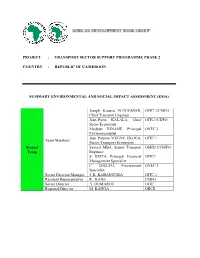

Project : Transport Sector Support Programme Phase 2

PROJECT : TRANSPORT SECTOR SUPPORT PROGRAMME PHASE 2 COUNTRY : REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON SUMMARY ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (ESIA) Joseph Kouassi N’GUESSAN, OITC.1/CMFO Chief Transport Engineer Jean-Pierre KALALA, Chief OITC1/CDFO Socio-Economist Modeste KINANE, Principal ONEC.3 Environmentalist Jean Paterne MEGNE EKOGA, OITC.1 Team Members Senior Transport Economist Project Samuel MBA, Senior Transport OSHD.2/CMFO Team Engineer S. KEITA, Principal Financial OITC1 Management Specialist C. DJEUFO, Procurement ONEC.3 Specialist Sector Division Manager J. K. KABANGUKA OITC.1 Resident Representative R. KANE CMFO Sector Director A. OUMAROU OITC Regional Director M. KANGA ORCE SUMMARY ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (ESIA) Programme Name : Transport Sector Support Programme Phase 2 SAP Code: P-CM-DB0-015 Country : Cameroon Department : OITC Division : OITC-1 1. INTRODUCTION This document is a summary of the Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) of the Transport Sector Support Programme Phase 2 which involves the execution of works on the Yaounde-Bafoussam-Bamenda road. The impact assessment of the project was conducted in 2012. This assessment seeks to harmonize and update the previous one conducted in 2012. According to national regulations, the Yaounde-Bafoussam-Babadjou road section rehabilitation project is one of the activities that require the conduct of a full environmental and social impact assessment. This project has been classified under Environmental Category 1 in accordance with the African Development Bank’s Integrated Safeguards System (ISS) of July 2014. This summary has been prepared in accordance with AfDB’s environmental and social impact assessment guidelines and procedures for Category 1 projects. -

Global Impacts of the Illegal Wildlife Trade Global Impacts of the Illegal Wildlife Trade

Global Impacts of the Illegal Wildlife Trade Trade Global Impacts of the Illegal Wildlife Global Impacts of the Illegal Wildlife Trade The Costs of Crime, Insecurity and Institutional Erosion Katherine Lawson and Alex Vines Katherine Lawson and Alex Vines February 2014 Chatham House, 10 St James’s Square, London SW1Y 4LE T: +44 (0)20 7957 5700 E: [email protected] F: +44 (0)20 7957 5710 www.chathamhouse.org Charity Registration Number: 208223 Global Impacts of the Illegal Wildlife Trade The Costs of Crime, Insecurity and Institutional Erosion Katherine Lawson and Alex Vines February 2014 © The Royal Institute of International Affairs, 2014 Chatham House (The Royal Institute of International Affairs) is an independent body which promotes the rigorous study of international questions and does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are the responsibility of the authors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the copyright holder. Please direct all enquiries to the publishers. Chatham House 10 St James’s Square London SW1Y 4LE T: +44 (0) 20 7957 5700 F: + 44 (0) 20 7957 5710 www.chathamhouse.org Charity Registration No. 208223 ISBN 978 1 78413 004 6 A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library. Cover image: © US Fish and Wildlife Service. Six tonnes of ivory were crushed by the Obama administration in November 2013. Designed and typeset by Soapbox Communications Limited www.soapbox.co.uk Printed and bound in Great Britain by Latimer Trend and Co Ltd The material selected for the printing of this report is manufactured from 100% genuine de-inked post-consumer waste by an ISO 14001 certified mill and is Process Chlorine Free. -

Cameroon |Far North Region |Displacement Report Round 15 | 03– 15 September 2018

Cameroon |Far North Region |Displacement Report Round 15 | 03– 15 September 2018 Cameroon | Far North Region | Displacement Report | Round 15 | 03– 15 September 2018 The opinions expressed in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries1. IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergovernmental organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to assist in meeting the operational challenges of migration, advance understanding of migration issues, encourage social and economic development through migration and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. International Organization for Migration Cameroon Mission Maroua Sub-Office UN House Comice Maroua Far North Region Cameroon Tel.: +237 222 20 32 78 E-mail: [email protected] Websites: https://ww.iom.int/fr/countries/cameroun and https://displacement.iom.int/cameroon All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. 1The maps included in this report are illustrative. The representations and the use of borders and geographic names may include errors and do not imply judgment on legal status of territories nor acknowledgement of borders by the Organization. -

Overview of Human Wildlife Conflict in Cameroon

Overview of Human Wildlife Conflict in Cameroon Poto: Etoga Gilles WWF Campo, 2011 By Antoine Justin Eyebe Guy Patrice Dkamela Dominique Endamana POVERTY AND CONSERVATION LEARNING GROUP DISCUSSION PAPER NO 05 February 2012 Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................ 3 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 4 2. Evidence of HWC in Cameroon............................................................................................ 4 3. Typology of HWC ................................................................................................................. 7 3.1 Crop destruction ........................................................................................................... 7 3.2 Attacks on domestic animals ..................................................................................... 10 3.3 Human death, injuries and damage to property ....................................................... 11 4. The Policy and Institutional Framework for Human-Wildlife Conflict Management at the State level in Cameroon ............................................................................................................ 11 4.1. Statutory instruments and institutions for HWC management ................................. 12 4.1.1 Protection of persons and property against animals ......................................... 12 4.1.2 Compensation -

Cop17 Prop 16

Original language: English and French1 CoP17 Prop. 16 CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________________ Seventeenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties Johannesburg (South Africa), 24 September – 5 October 2016 CONSIDERATION OF PROPOSALS FOR AMENDMENT OF APPENDICES I AND II A. Proposal 1. The inclusion of all populations of Loxodonta africana (African elephant) in Appendix I through the transfer from Appendix II to Appendix I of the populations of Botswana, Namibia, South Africa and Zimbabwe. 2. This amendment is justified according to the following criteria under Annex 1 of Resolution Conf. 9.24 (Rev. CoP16), Criteria for amendment of Appendices I and II: "C. A marked decline in population size in the wild, which has been either: i) observed as ongoing or as having occurred in the past (but with a potential to resume); or ii) inferred or projected on the basis of any one of the following: - levels or patterns of exploitation; - high vulnerability to either intrinsic or extrinsic factors" B. Proponent Benin, Burkina Faso, Central African Republic, Chad, Ethiopia, Kenya, Liberia, Mali, the Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sri Lanka and Uganda 2: C. Supporting statement 1. Taxonomy 1.1 Class: Mammalia 1.2 Order: Proboscidea 1.3 Family: Elephantidae 1.4 Genus, species or subspecies, including author and year: Loxodonta africana (Blumenbach, 1797) 1.5 Scientific synonyms: 1 This document has been provided in these languages by the author(s). 2 The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CITES Secretariat (or the United Nations Environment Programme) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Squander Cover

The importance and vulnerability of the world’s protected areas Squandering THREATS TO PROTECTED AREAS SQUANDERING PARADISE? The importance and vulnerability of the world’s protected areas By Christine Carey, Nigel Dudley and Sue Stolton Published May 2000 By WWF-World Wide Fund For Nature (Formerly World Wildlife Fund) International, Gland, Switzerland Any reproduction in full or in part of this publication must mention the title and credit the above- mentioned publisher as the copyright owner. © 2000, WWF - World Wide Fund For Nature (Formerly World Wildlife Fund) ® WWF Registered Trademark WWF's mission is to stop the degradation of the planet's natural environment and to build a future in which humans live in harmony with nature, by: · conserving the world's biological diversity · ensuring that the use of renewable natural resources is sustainable · promoting the reduction of pollution and wasteful consumption Front cover photograph © Edward Parker, UK The photograph is of fire damage to a forest in the National Park near Andapa in Madagascar Cover design Helen Miller, HMD, UK 1 THREATS TO PROTECTED AREAS Preface It would seem to be stating the obvious to say that protected areas are supposed to protect. When we hear about the establishment of a new national park or nature reserve we conservationists breathe a sigh of relief and assume that the biological and cultural values of another area are now secured. Unfortunately, this is not necessarily true. Protected areas that appear in government statistics and on maps are not always put in place on the ground. Many of those that do exist face a disheartening array of threats, ranging from the immediate impacts of poaching or illegal logging to subtle effects of air pollution or climate change. -

Proceedingsnord of the GENERAL CONFERENCE of LOCAL COUNCILS

REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN Peace - Work - Fatherland Paix - Travail - Patrie ------------------------- ------------------------- MINISTRY OF DECENTRALIZATION MINISTERE DE LA DECENTRALISATION AND LOCAL DEVELOPMENT ET DU DEVELOPPEMENT LOCAL Extrême PROCEEDINGSNord OF THE GENERAL CONFERENCE OF LOCAL COUNCILS Nord Theme: Deepening Decentralization: A New Face for Local Councils in Cameroon Adamaoua Nord-Ouest Yaounde Conference Centre, 6 and 7 February 2019 Sud- Ouest Ouest Centre Littoral Est Sud Published in July 2019 For any information on the General Conference on Local Councils - 2019 edition - or to obtain copies of this publication, please contact: Ministry of Decentralization and Local Development (MINDDEVEL) Website: www.minddevel.gov.cm Facebook: Ministère-de-la-Décentralisation-et-du-Développement-Local Twitter: @minddevelcamer.1 Reviewed by: MINDDEVEL/PRADEC-GIZ These proceedings have been published with the assistance of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) through the Deutsche Gesellschaft für internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH in the framework of the Support programme for municipal development (PROMUD). GIZ does not necessarily share the opinions expressed in this publication. The Ministry of Decentralisation and Local Development (MINDDEVEL) is fully responsible for this content. Contents Contents Foreword ..............................................................................................................................................................................5 -

Scaringe, Christina, General Counsel

February 12, 2019 Connecticut General Assembly Environment Committee Via email RE: In support of SB20, An Act Prohibiting the Import, Sale, and Possession of African Elephants, Lions, Leopards, Black Rhinoceros, White Rhinoceros, and Giraffes, and HB5394, An Act Concerning the Sale and Trade of Ivory and Rhinoceros Horn in the State. Good afternoon to the Environment Committee Co-Chair Cohen, Co-Chair Demicco, Vice Chair Gresko, Vice Chair Kushner, Ranking Member Harding, Ranking Member Miner, and Members Arconti, Borer, Dillon, Dubitsky, Gucker, Haskell, Hayes, Horn, Kennedy, MacLachlan, McGorty, Michel, Mushinsky, O’Dea, Palm, Piscopo, Rebimbas, Reyes, Ryan, Simms, Slap, Vargas, Wilson, Young, and Zupkus: Animal Defenders International offers the following in support of SB20 (sponsored by Senator Duff, Representative KupchicK, and Representative Michel, and drafted as an ENV Committee Bill) and HB5394 (sponsored by Representative Bolinsky and drafted as an ENV Committee Bill), with our thanks to the sponsors for their efforts to address the challenges facing these species, including, among other things, legal and illegal trade. In its 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, the UN General Assembly underscored the import of sustainable tourism that protects wildlife, directing Member States to “prevent, combat, and eradicate the illegal trade in wildlife, on both the supply and demand sides.”1 To that end, the US should not promote or enable the demand for trophy hunting, given its demonstrated ties to illicit trafficking; however, US federal policy has reversed in recent years to do just that. For example, the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) instituted its inaptly named International Wildlife Conservation Council to promote, expand, and enable international trophy hunting and to ease trade in wildlife products, including the import of threatened species as hunting trophies, into the US. -

Strategy for the Conservation of West African Elephants

STRATEGY FOR THE CONSERVATION OF WEST AFRICAN ELEPHANTS (Updated version- March 2005) IUCN 13 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 2. INTRODUCTION 5 3. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND ..................................................................................... 7 4. CURRENT STATUS 7 4.1. Distribution and Numbers 7 4.2. Trends 9 4.3. Habitat Management 9 5..ACTION TO BE UNDERTAKEN BY THE STRATEGY ............................................. 10 6. RESULTS TO BE OBTAINED DURING IMPLEMENTION OF THE STRATEGY 11 6.1. Result 1: Information Necessary For Management................................................... 11 6.1.1. Rationale.......................................................................................................... 11 6.1.2. Activities.......................................................................................................... 11 6.2. Result 2: Better Understanding And Effective Control Of The Ivory Trade ............ 12 6.2.1. Rationale.......................................................................................................... 12 6.2.2. Activities.......................................................................................................... 13 6.3. Result 3: Enhanced Institutional Capacity For Elephant Management..................... 13 6.3.1. Rationale.......................................................................................................... 13 6.3.2. Activities.........................................................................................................