Using Community Knowledge to Identify Potential Hotspots of Mammal Diversity in Southeastern Nepal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Keshav Ravi by Keshav Ravi

by Keshav Ravi by Keshav Ravi Preface About the Author In the whole world, there are more than 30,000 species Keshav Ravi is a caring and compassionate third grader threatened with extinction today. One prominent way to who has been fascinated by nature throughout his raise awareness as to the plight of these animals is, of childhood. Keshav is a prolific reader and writer of course, education. nonfiction and is always eager to share what he has learned with others. I have always been interested in wildlife, from extinct dinosaurs to the lemurs of Madagascar. At my ninth Outside of his family, Keshav is thrilled to have birthday, one personal writing project I had going was on the support of invested animal advocates, such as endangered wildlife, and I had chosen to focus on India, Carole Hyde and Leonor Delgado, at the Palo Alto the country where I had spent a few summers, away from Humane Society. my home in California. Keshav also wishes to thank Ernest P. Walker’s Just as I began to explore the International Union for encyclopedia (Walker et al. 1975) Mammals of the World Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List species for for inspiration and the many Indian wildlife scientists India, I realized quickly that the severity of threat to a and photographers whose efforts have made this variety of species was immense. It was humbling to then work possible. realize that I would have to narrow my focus further down to a subset of species—and that brought me to this book on the Endangered Mammals of India. -

Legacies and Gifts

202 Oryx Oryx 100% Fund The following grants have been made from the Oryx 100% Fund: £500 to the Durham University Himalayan Expedition to complete a study of the Himalayan tahr in Langtang National Park; £500 to the University of East Anglia Nepal Expedition for surveys of the pygmy hog and hispid hare; £500 to Professor Daniel Torres-Navarro, University of Chile, for studies of the fur seal on Juan Fernandez; £300 to Katherine Homewood and Margaret Renshaw to study infant development and socialisation in the Tana mangabey, part of a con- tinuing study of this endangered monkey; £300 to Godofredo Stutzin for camera equipment and binoculars for the use of guards protecting the Chilean huemul; £250 to Dr E. O. Moll, East Illinois University, for development of a management programme for Malaysian sea and river turtles; £250 to Sompoad Srikosarmatara, Mahidol University, Bangkok, for a study of the pileated gibbon in the Khao Sqi Dao Wildlife Sanctuary; £250 to the Wildlife and Nature Protection Society of Sri Lanka to offset costs of conservation leaflets for tourists {Oryx, Dec. 1977, p.l 17); £20 to J. A. Fowler of Leicester Polytechnic for ecological studies in the maritime approaches to the Sullom Voe Oil Terminal, Shetland. Legacies and Gifts FPS is most grateful for the following gifts of £20 and over, totalling £9794, and for other smaller gifts received between October 1977 and March 1978: Legacies L. Sheriff £6300 Mrs G.H. Soward £25 Gifts Anonymous £2000 Dr A.A. Spriggs £50 Mrs V.H. Williams £25 Oryx 100% Fund St Katharine's Fund (including £450 earmarked for the East African Wild Life Society) £750 F. -

Controlled Animals

Environment and Sustainable Resource Development Fish and Wildlife Policy Division Controlled Animals Wildlife Regulation, Schedule 5, Part 1-4: Controlled Animals Subject to the Wildlife Act, a person must not be in possession of a wildlife or controlled animal unless authorized by a permit to do so, the animal was lawfully acquired, was lawfully exported from a jurisdiction outside of Alberta and was lawfully imported into Alberta. NOTES: 1 Animals listed in this Schedule, as a general rule, are described in the left hand column by reference to common or descriptive names and in the right hand column by reference to scientific names. But, in the event of any conflict as to the kind of animals that are listed, a scientific name in the right hand column prevails over the corresponding common or descriptive name in the left hand column. 2 Also included in this Schedule is any animal that is the hybrid offspring resulting from the crossing, whether before or after the commencement of this Schedule, of 2 animals at least one of which is or was an animal of a kind that is a controlled animal by virtue of this Schedule. 3 This Schedule excludes all wildlife animals, and therefore if a wildlife animal would, but for this Note, be included in this Schedule, it is hereby excluded from being a controlled animal. Part 1 Mammals (Class Mammalia) 1. AMERICAN OPOSSUMS (Family Didelphidae) Virginia Opossum Didelphis virginiana 2. SHREWS (Family Soricidae) Long-tailed Shrews Genus Sorex Arboreal Brown-toothed Shrew Episoriculus macrurus North American Least Shrew Cryptotis parva Old World Water Shrews Genus Neomys Ussuri White-toothed Shrew Crocidura lasiura Greater White-toothed Shrew Crocidura russula Siberian Shrew Crocidura sibirica Piebald Shrew Diplomesodon pulchellum 3. -

Endangered Species

Not logged in Talk Contributions Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Endangered species From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Main page Contents For other uses, see Endangered species (disambiguation). Featured content "Endangered" redirects here. For other uses, see Endangered (disambiguation). Current events An endangered species is a species which has been categorized as likely to become Random article Conservation status extinct . Endangered (EN), as categorized by the International Union for Conservation of Donate to Wikipedia by IUCN Red List category Wikipedia store Nature (IUCN) Red List, is the second most severe conservation status for wild populations in the IUCN's schema after Critically Endangered (CR). Interaction In 2012, the IUCN Red List featured 3079 animal and 2655 plant species as endangered (EN) Help worldwide.[1] The figures for 1998 were, respectively, 1102 and 1197. About Wikipedia Community portal Many nations have laws that protect conservation-reliant species: for example, forbidding Recent changes hunting , restricting land development or creating preserves. Population numbers, trends and Contact page species' conservation status can be found in the lists of organisms by population. Tools Extinct Contents [hide] What links here Extinct (EX) (list) 1 Conservation status Related changes Extinct in the Wild (EW) (list) 2 IUCN Red List Upload file [7] Threatened Special pages 2.1 Criteria for 'Endangered (EN)' Critically Endangered (CR) (list) Permanent link 3 Endangered species in the United -

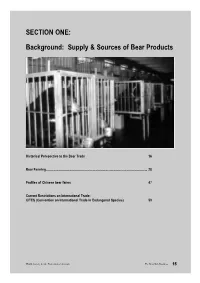

SECTION ONE: Background: Supply & Sources of Bear Products

SECTION ONE: Background: Supply & Sources of Bear Products Historical Perspective to the Bear Trade 16 Bear Farming 28 Profiles of Chinese bear farms 47 Current Restrictions on International Trade: CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species) 59 World Society for the Protection of Animals The Bear Bile Business 15 Historical Perspective to the Bear Trade Victor Watkins Traditonal Chinese Medicine and the growth of the modern trade in bear products The use of herbs to cure illness can be traced back over 4,000 years in China. The earliest medicinal literature (Shen-nong Ben Cao) dates back to 482 BC and records 365 types of medicinal issues. One of the most famous Chinese herbals, (Ben Cao Gang Mu) was written by Li Shi-zhen during the Ming dynasty (1590). This work lists 1,892 types of herbs used as medicine. In the above mentioned literature, animal ingredients make up less than 10% of the medicinal ingredients, and the majority of those animal parts are insects. There is very little use of mammal body parts listed in these early Chinese traditional medicines1. The use of bear parts in medicines in China dates back over 3,000 years. Medicinal uses for bear gall bladder first appeared in writing in the seventh century A.D. in the Materia Medica of Medicinal Properties2. The use of bear bile has since spread to other Asian countries such as Korea and Japan where it has been adopted for use in local traditional medicines. Plant and animal products which are selected for use in Chinese medicine are classified according to their properties. -

Heart Rate During Hyperphagia Differs Between Two Bear Species

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Brage INN Physiology Heart rate during hyperphagia differs royalsocietypublishing.org/journal/rsbl between two bear species Boris Fuchs1,†, Koji Yamazaki2,†, Alina L. Evans1, Toshio Tsubota3, Shinsuke Koike4,5, Tomoko Naganuma5 and Jon M. Arnemo1,6 Research 1Department of Forestry and Wildlife Management, Faculty of Applied Ecology and Agricultural Sciences, Cite this article: Fuchs B, Yamazaki K, Evans Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences, Campus Evenstad, 2418 Elverum, Norway 2Department of Forest Science, Tokyo University of Agriculture, 1-1-1 Sakuragaoka, Setagaya-Ku, Tokyo, Japan AL, Tsubota T, Koike S, Naganuma T, Arnemo 3Department of Environmental Veterinary Sciences, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Hokkaido University, Kita18, JM. 2019 Heart rate during hyperphagia differs Nishi9, Kita-Ku, Sapporo, Hokkaido, Japan between two bear species. Biol. Lett. 15: 4Institute of Global Innovation Research, and 5United Graduate School of Agricultural Science, Tokyo University 20180681. of Agriculture and Technology, 3-5-8 Saiwai, Fuchu-city, Tokyo, Japan 6Department of Wildlife, Fish and Environmental Studies, Faculty of Forest Sciences, Swedish University of http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2018.0681 Agricultural Sciences, 901 83, Umea˚, Sweden BF, 0000-0003-3412-3490; ALE, 0000-0003-0513-4887 Received: 28 September 2018 Hyperphagia is a critical part of the yearly cycle of bears when they gain fat reserves before entering hibernation. We used heart rate as a proxy to com- Accepted: 17 December 2018 pare the metabolic rate between the Asian black bear (Ursus thibetanus)in Japan and the Eurasian brown bear (Ursus arctos) in Sweden from summer into hibernation. -

SCHEDULE I (Sections 2, 8,9,11, 40,41, 48,51, 61 & 62)

SCHEDULE I (Sections 2, 8,9,11, 40,41, 48,51, 61 & 62) PART I MAMMALS [1. Andaman Wild pig (Sus sorofa andamanensis)] 2[1-A. Bharal (Ovisnahura)] 2[1 -B. Binturong (Arctictis Binturong)] 2. Black Buck (Antelope cervicapra) 2[2-A. •*•] 3. Brow-antlered Deer or Thamin (Cervus eldi) 3[3-A. Himalayan Brown bear (Ursus Arctos)] 3[3-B. Capped Langur (Presbytis pileatus)] 4. Caracal (Felis caracal) [4-A. Catecean specials] 5. Cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) 4[5-A. Chinese Pangolin (Mainis pentadactyla)] '[5-B. Chinkara or India Gazelle (Gazella gazella bennetti)] 6. Clouded Leopard (Neofelis nebulosa) 2[6-A. Crab-eating Macaque (Macaca irus umbrosa)] 2[6-B. Desert Cat (Felis libyca)] 3[6-C Desert fox (Vulpes bucapus)] 7. Dugong (Dugong dugon) 2[7-A Ermine (Mustele erminea)] 8. Fishing Cat (Felis viverrina) a[8-A Four-horned antelope (Tetraceros quadricomis)] 2[8-B. *••] 3[8-C ***] 3[8-D. Gangetic dolphin (Platanista gangetica)] 3[8-E. Gaur or Indian bison (Bos gaurus)] 9. Golden Cat (Felis temmincki) 10. Golden Langur (Presbytis geei) 3[10-A. Giant squirrel (Ratufa macroura)] [10-B. Himalayan Ibex (Capra ibex)] ' [10-C. Himalayan Tahr (Hemitragus jemlahicus)] 11. Hispid Hare (Caprolagus hispidus) 3[11-A. Hog badgar (Arconyx collaris)] 12. Hoolock (Hyloba tes hoolock) 1 Vide Notification No. FJ11012/31/76 FRY(WL), dt. 5-10-1977. 2 Vide Notification No. Fl-28/78 FRY(WL), dt. 9-9-1980. 3 Vide Notification No. S.O. 859(E), dt. 24-11-1986. 4 Vide Notification No. F] 11012/31 FRY(WL), dt. -

Press Release

Press Release Pygmy hog is reintroduced in Sonai Rupai, Assam – creating the second wild population of this highly endangered species in the world Twelve years after six wild pygmy hogs (two males and four females) were captured from their last surviving population in Manas National Park of Assam, sixteen captive bred hogs (s) are now being released to the wild. Seven male and nine female hogs, belonging to three social groups, are being released in Sonai Rupai Wildlife Sanctuary as the part of a proposed series of reintroduction projects in selected sites in Assam, conducted under the auspices of the Pygmy Hog Conservation Programme (PHCP). They were bred at PHCP research and breeding centre in Basistha near Guwahati before being transferred to a specially constructed ‘pre-release’ facility in Potasali near Nameri National Park. Under the ‘soft release’ procedure, these hogs were maintained in large ‘pre-release’ enclosures for five months and have now been transferred to final ‘release’ enclosures in Sonai Rupai. They will be released from these enclosures to the wild within the next two to three weeks. The new population of released hogs will be monitored using direct and indirect methods. The Pygmy Hog Conservation Programme is a collaborative project of Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust (DWCT), Pigs Peccaries & Hippos Specialist Group (PPHSG) of World Conservation Union’s Species Survival Commission (IUCN-SSC), Forest Department of the Government of Assam, and the Ministry of Environment & Forests of Government of India. The Programme is financially supported by DWCT and currently also by the UK Government’s Darwin Initiative. EcoSystems-India, the local partner organisation of DWCT and PPHSG, is assisting PHCP implement its activities in Assam and is working closely with local communities and other stakeholders, including some NGOs such as Aaranyak and the Centre for Environment Education (CEE), to improve awareness about the species and the management of its grassland habitats. -

Wild Pig, Peccary and Hippo TAG AKA Picco TAG TAG Officers

Wild Pig, Peccary and Hippo TAG AKA Picco TAG TAG Officers TAG Chair Martin Ramirez, Woodland Park Zoo Vice Chair Jeff Holland Los Angeles Zoo and Botanical Gardens Secretary Dawn Petefish Peoria Zoo Advisors Vet Advisor Cora Singleton Reproductive Advisors Annie Newell-Fugate Endocrine Advisor for Hippos Catharine Wheaton TAG Steering Committee RoxAnna Breitigan, The Living Desert Joe Forys, Audubon Zoo Randy Reiches, San Diego Safari Park John Davis, Riverbanks Zoo & Garden Penny Kalk, Bronx Zoo Lisa Smith, Great Plains Zoo & Delbridge Museum of Natural History Program Highlights Pygmy Hippo River Hippo Christie Eddie, Henry Doorly Zoo John Davis, Riverbanks Zoo Help recruit new institutions and • Help with solution for encourage them to support Pygmy extra males Hippo in situ projects. • New institutions or institutions interested in housing additional animals should contact the SSP Coordinator Program Highlights Babirusa Visayan Warty Pig Jeff Holland, Los Angeles Zoo Craig Miller, Jacksonville Zoo • GSMP candidate More support from holders for in- situ conservation projects. • SSP is exporting 3.2 to EAZA. Program Highlights Collared Peccary Chacoan Peccary Jim Haigwood, Dennis Meritt Los Angeles Zoo • Financial support of in-situ work in Paraguay at Proyecto Tagua • Ship out your collared peccaries and replace them • Encourage institutions to ship out with Chacoan peccaries collared peccaries and replace them with Chacoan peccaries • Do not breed your collared peccaries. • If possible, incorporate your collared peccaries in a mixed -

(Bubalus Bubalis) in NEPAL: RECOMMENDED MANAGEMENT ACTION in the FACE of UNCERTAINTY for a CRITICALLY ENDANGERED SPECIES

Contents TIGERPAPER A Translocation Proposal for Wild Buffalo in Nepal................... 1 Eucalyptus – Bane or Boon?................................................... 8 Status and Distribution of Wild Cattle in Cambodia.................... 9 Reptile Richness and Diversity In and Around Gir Forest........... 15 A Comparison of Identification Techniques for Predators on Artificial Nests................................................................... 20 Devastating Flood in Kaziranga National Park............................ 24 Bird Damage to Guava and Papaya........................................... 27 Death of an Elephant by Sunstroke in Orissa............................. 31 Msc in Forest and Nature Conservation for Tropical Areas......... 32 FOREST NEWS Report of an International Conference on Community Involvement in Fire Management............................................ 1 ASEAN Senior Officials Endorse Code of Practice for Forest Harvesting.................................................................. 4 Asian Model Forests Develop Criteria and Indicators Guidelines............................................................................. 4 East Asian Countries Pledge Action on Illegal Forest Activities.............................................................................. 6 South Pacific Ministers Consider Forestry Issues........................ 9 Tropical Ecosystems, Structure, Diversity and Human Welfare.. 10 Draft Webpage for International Weem Network......................... 10 New FAO Forestry Publications............................................... -

Thirty Years of Managing Suklaphanta, the Swamp Deer and the Tiger

Thirty Years of Managing Suklaphanta, the Swamp Deer and the Tiger: Issues and Strategies -Buddi Sagar Poudel* Conservation values of Suklaphanta Protected areas are widely considered to be among the most effective means of conserving biological diversity in situ. Protected area management received a real thrust in the 1970s in Nepal. Not only protected areas came to be added, but also action on both their protection and conservation was intensified. The first organized approach to managing Swamp deer in Nepal dates back to the year 1976. Suklaphanta Wildlife Reserve (SWR) was established in 1976. It is the only protected area which has been set up exclusively for Swamp deer. The presence of world's largest herd of Swamp deer in Suklaphanta makes SWR a globally important site for conservation standpoint. SWR is a home to a wide range of vertebrates. It is home to endangered wildlife species including Tiger, Elephant, Rhino, Swamp deer, Hispid hare, Pigmy hug etc. In fact, it is the largest refuge of already endangered Bengal Florican and harbors the only hispid hare population in Nepal. Famous for its rich and diverse biodiversity, SWR also has the pride of having the highest density of Royal Bengal Tiger in any tiger habitats in Asia. The vegetation of the park is a mosaic of great expenses of grasslands primarily of tall, dense grasses interspersed with deciduous forests, interconnected streams and swamps makes the area suitable for many rare and endangered species. Schaff (1987) described eight vegetation types in the reserve. Sal forest, Sal savanna, mixed deciduous forest, Khair- Sissoo forest, dry grassland, seasonal wet grasslands, lowland savanna and marsh. -

Hubei Shennongjia

ASIA / PACIFIC HUBEI SHENNONGJIA CHINA Laojunshan Component of the property - © IUCN Bruce Jefferies China - Hubei Shennongjia WORLD HERITAGE NOMINATION – IUCN TECHNICAL EVALUATION HUBEI SHENNONGJIA (CHINA) – ID 1509 IUCN RECOMMENDATION TO WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE: To inscribe the property under natural criteria. Key paragraphs of Operational Guidelines: Paragraph 77: Nominated property meets World Heritage criteria. Paragraph 78: Nominated property meets integrity and protection and management requirements. 1. DOCUMENTATION S. and Hong Qian. Global Significance of Plant Diversity in China. In The Plants of China: A a) Date nomination received by IUCN: 16 March Companion to the Flora of China (2015). Huang, J. H., 2015 Chen, J.H., Ying, J.S., and Ke‐Ping M. Features and distribution patterns of Chinese endemic seed plant b) Additional information officially requested from species. Journal of Systematics and Evolution 49, no. and provided by the State Party: On 6 September 2 (2011): 81-94. Li, Y. (2004). The effect of forest 2015, the State Party responded to issues which arose clear-cutting on habitat use in Sichuan snub-nosed during the course of the IUCN field evaluation mission. monkey (Rhinopithecus roxellana) in Shennongjia The letter, with accompanying maps, addressed a Nature Reserve, China. Primates 45.1 69-72.. López- range of issues and confirmed extensions to the Pujol, J., et al. (2011). Mountains of Southern China as nominated area and buffer zone in the Badong County “plant museums” and “plant cradles”: evolutionary and area. Following the IUCN World Heritage Panel a conservation insights. Mountain Research and progress report was sent to the State Party on 16 Development,31(3), 261-269.