Gender Discrimination in the Classical Conducting World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Juilliard Orchestra Marin Alsop, Conductor Daniel Ficarri, Organ Daniel Hass, Cello

Saturday Evening, January 25, 2020, at 7:30 The Juilliard School presents Juilliard Orchestra Marin Alsop, Conductor Daniel Ficarri, Organ Daniel Hass, Cello SAMUEL BARBER (1910–81) Toccata Festiva (1960) DANIEL FICARRI, Organ DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH (1906–75) Cello Concerto No. 2 in G major, Op. 126 (1966) Largo Allegretto Allegretto DANIEL HASS, Cello Intermission CHRISTOPHER ROUSE (1949–2019) Processional (2014) JOHANNES BRAHMS (1833–97) Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 73 (1877) Allegro non troppo Adagio non troppo Allegretto grazioso Allegro con spirito Performance time: approximately 1 hour and 50 minutes, including an intermission This performance is made possible with support from the Celia Ascher Fund for Juilliard. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not permitted in this auditorium. Information regarding gifts to the school may be obtained from the Juilliard School Development Office, 60 Lincoln Center Plaza, New York, NY 10023-6588; (212) 799-5000, ext. 278 (juilliard.edu/giving). Alice Tully Hall Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. Juilliard About the Program the organ’s and the orchestra’s full ranges. A fluid approach to rhythm and meter By Jay Goodwin provides momentum and bite, and intricate passagework—including a dazzling cadenza Toccata Festiva for the pedals that sets the organist’s feet SAMUEL BARBER to dancing—calls to mind the great organ Born: March 9, 1910, in West Chester, music of the Baroque era. Pennsylvania Died: January 23, 1981, in New York City Cello Concerto No. 2 in G major, Op. 126 DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH In terms of scale, pipe organs are Born: September 25, 1906, in Saint Petersburg different from every other type of Died: August 9, 1975, in Moscow musical instrument, and designing and assembling a new one can be a challenge There are several reasons that of architecture and engineering as complex Shostakovich’s Cello Concerto No. -

National Museum of American Jewish History, Leonard Bernstein

Narrative Section of a Successful Application The attached document contains the grant narrative and selected portions of a previously funded grant application. It is not intended to serve as a model, but to give you a sense of how a successful application may be crafted. Every successful application is different, and each applicant is urged to prepare a proposal that reflects its unique project and aspirations. Prospective applicants should consult the Research Programs application guidelines at https://www.neh.gov/grants/public/public-humanities- projects for instructions. Applicants are also strongly encouraged to consult with the NEH Division of Research Programs staff well before a grant deadline. Note: The attachment only contains the grant narrative and selected portions, not the entire funded application. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. Project Title: Leonard Bernstein: The Power of Music Institution: National Museum of American Jewish History Project Director: Ivy Weingram Grant Program: America's Historical and Cultural Organizations: Planning Grants 1100 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W., Rm. 426, Washington, D.C. 20506 P 202.606.8269 F 202.606.8557 E [email protected] www.neh.gov THE NATURE OF THE REQUEST The National Museum of American Jewish History (NMAJH) respectfully requests a planning grant of $50,000 from the National Endowment for the Humanities to support the development of the special exhibition Leonard Bernstein: The Power of Music (working title), opening in March 2018 to celebrate the centennial year of Bernstein’s birth. -

100 Years: a Century of Song 1950S

100 Years: A Century of Song 1950s Page 86 | 100 Years: A Century of song 1950 A Dream Is a Wish Choo’n Gum I Said my Pajamas Your Heart Makes / Teresa Brewer (and Put On My Pray’rs) Vals fra “Zampa” Tony Martin & Fran Warren Count Every Star Victor Silvester Ray Anthony I Wanna Be Loved Ain’t It Grand to Be Billy Eckstine Daddy’s Little Girl Bloomin’ Well Dead The Mills Brothers I’ll Never Be Free Lesley Sarony Kay Starr & Tennessee Daisy Bell Ernie Ford All My Love Katie Lawrence Percy Faith I’m Henery the Eighth, I Am Dear Hearts & Gentle People Any Old Iron Harry Champion Dinah Shore Harry Champion I’m Movin’ On Dearie Hank Snow Autumn Leaves Guy Lombardo (Les Feuilles Mortes) I’m Thinking Tonight Yves Montand Doing the Lambeth Walk of My Blue Eyes / Noel Gay Baldhead Chattanoogie John Byrd & His Don’t Dilly Dally on Shoe-Shine Boy Blues Jumpers the Way (My Old Man) Joe Loss (Professor Longhair) Marie Lloyd If I Knew You Were Comin’ Beloved, Be Faithful Down at the Old I’d Have Baked a Cake Russ Morgan Bull and Bush Eileen Barton Florrie Ford Beside the Seaside, If You were the Only Beside the Sea Enjoy Yourself (It’s Girl in the World Mark Sheridan Later Than You Think) George Robey Guy Lombardo Bewitched (bothered If You’ve Got the Money & bewildered) Foggy Mountain Breakdown (I’ve Got the Time) Doris Day Lester Flatt & Earl Scruggs Lefty Frizzell Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo Frosty the Snowman It Isn’t Fair Jo Stafford & Gene Autry Sammy Kaye Gordon MacRae Goodnight, Irene It’s a Long Way Boiled Beef and Carrots Frank Sinatra to Tipperary -

Xm Radio to Broadcast New Series of Baltimore Symphony Orchestra Concerts in 2007-2008 Season

NEWS RELEASE XM RADIO TO BROADCAST NEW SERIES OF BALTIMORE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA CONCERTS IN 2007-2008 SEASON 6/14/2007 SEPT. 27 SERIES DEBUT TO BE BROADCAST LIVE FROM STRATHMORE, FEATURING MARIN ALSOP’S INAUGURAL CONCERT AS BSO MUSIC DIRECTOR Washington, D.C., and Baltimore, Md. June 14, 2007 – XM, the nation’s leading satellite radio service with more than 8 million subscribers, and the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra (BSO) announced today that XM will broadcast eight performances during the Baltimore Symphony’s 2007-2008 season on XM Classics (XM 110), one of XM’s three classical music channels. The series will debut with a live broadcast on September 27, 2007, the inaugural concert of the music directorship of Marin Alsop, the dynamic conductor who that evening will become the first female music director of a major American orchestra. This series marks the BSO’s foray into satellite radio, gaining exposure for the orchestra to a much broader national audience as it enters a new artistic chapter under Marin Alsop. The historic inaugural concert marking Maestra Alsop’s directorship features John Adams’ Fearful Symmetries, and a hallmark of Alsop’s repertoire, Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 5, and will be broadcast live on XM Classics from the Music Center at Strathmore in N. Bethesda, Md. at 8 p.m. ET on Thursday, September 27, with an encore broadcast on Sunday, September 30, at 3 p.m. ET. The live broadcast will be the first of its kind at the Music Center at Strathmore since the performing arts venue opened in February 2005. -

Wwciguide January 2017.Pdf

Air Check The Guide Dear Member, The Member Magazine for Happy New Year! January is always a very exciting month for us as we often debut some of the WTTW and WFMT Renée Crown Public Media Center most highly-anticipated series and content of the year. And so it goes, we are thrilled to bring you 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue what we hope will be the next Masterpiece blockbuster series, about the epic life of Queen Victoria, Chicago, Illinois 60625 which will fill the Sunday night time slot that Downton Abbey held to Main Switchboard great success. Following Victoria from the time she becomes Queen (773) 583-5000 through her passionate courtship and marriage to Prince Albert, Member and Viewer Services the lavish premiere season of Victoria dramatizes the romance and (773) 509-1111 x 6 reign of the girl behind the famous monarch. Also, join us for new WFMT Radio Networks (773) 279-2000 seasons of Sherlock with Benedict Cumberbatch and Mercy Street, Chicago Production Center the homegrown drama series set during the Civil War. Leading up (773) 583-5000 to both of these season premieres, you can catch up with an all-day Websites marathon. wttw.com On January 16, we will debut an all-new channel and live stream wfmt.com offering for kids! You can find our new WTTW/PBS Kids 24/7 service President & CEO free on over-the-air channel 11-4, Comcast digital channel 368, and Daniel J. Schmidt RCN channel 39. Or watch the live stream on wttw.com, pbskids.org, and on the PBS KIDS Video COO & CFO Reese Marcusson App. -

Lister); an American Folk Rhapsody Deutschmeister Kapelle/JULIUS HERRMANN; Band of the Welsh Guards/Cap

Guild GmbH Guild -Light Catalogue Bärenholzstrasse 8, 8537 Nussbaumen, Switzerland Tel: +41 52 742 85 00 - e-mail: [email protected] CD-No. Title Track/Composer Artists GLCD 5101 An Introduction Gateway To The West (Farnon); Going For A Ride (Torch); With A Song In My Heart QUEEN'S HALL LIGHT ORCHESTRA/ROBERT FARNON; SIDNEY TORCH AND (Rodgers, Hart); Heykens' Serenade (Heykens, arr. Goodwin); Martinique (Warren); HIS ORCHESTRA; ANDRE KOSTELANETZ & HIS ORCHESTRA; RON GOODWIN Skyscraper Fantasy (Phillips); Dance Of The Spanish Onion (Rose); Out Of This & HIS ORCHESTRA; RAY MARTIN & HIS ORCHESTRA; CHARLES WILLIAMS & World - theme from the film (Arlen, Mercer); Paris To Piccadilly (Busby, Hurran); HIS CONCERT ORCHESTRA; DAVID ROSE & HIS ORCHESTRA; MANTOVANI & Festive Days (Ancliffe); Ha'penny Breeze - theme from the film (Green); Tropical HIS ORCHESTRA; L'ORCHESTRE DEVEREAUX/GEORGES DEVEREAUX; (Gould); Puffin' Billy (White); First Rhapsody (Melachrino); Fantasie Impromptu in C LONDON PROMENADE ORCHESTRA/ WALTER COLLINS; PHILIP GREEN & HIS Sharp Minor (Chopin, arr. Farnon); London Bridge March (Coates); Mock Turtles ORCHESTRA; MORTON GOULD & HIS ORCHESTRA; DANISH STATE RADIO (Morley); To A Wild Rose (MacDowell, arr. Peter Yorke); Plink, Plank, Plunk! ORCHESTRA/HUBERT CLIFFORD; MELACHRINO ORCHESTRA/GEORGE (Anderson); Jamaican Rhumba (Benjamin, arr. Percy Faith); Vision in Velvet MELACHRINO; KINGSWAY SO/CAMARATA; NEW LIGHT SYMPHONY (Duncan); Grand Canyon (van der Linden); Dancing Princess (Hart, Layman, arr. ORCHESTRA/JOSEPH LEWIS; QUEEN'S HALL LIGHT ORCHESTRA/ROBERT Young); Dainty Lady (Peter); Bandstand ('Frescoes' Suite) (Haydn Wood) FARNON; PETER YORKE & HIS CONCERT ORCHESTRA; LEROY ANDERSON & HIS 'POPS' CONCERT ORCHESTRA; PERCY FAITH & HIS ORCHESTRA; NEW CONCERT ORCHESTRA/JACK LEON; DOLF VAN DER LINDEN & HIS METROPOLE ORCHESTRA; FRANK CHACKSFIELD & HIS ORCHESTRA; REGINALD KING & HIS LIGHT ORCHESTRA; NEW CONCERT ORCHESTRA/SERGE KRISH GLCD 5102 1940's Music In The Air (Lloyd, arr. -

PRELUDE, FUGUE News for Friends of Leonard Bernstein RIFFS Spring/Summer 2004 the Leonard Bernstein School Improvement Model: More Findings Along the Way by Dr

PRELUDE, FUGUE News for Friends of Leonard Bernstein RIFFS Spring/Summer 2004 The Leonard Bernstein School Improvement Model: More Findings Along the Way by Dr. Richard Benjamin THE GRAMMY® FOUNDATION eonard Bernstein is cele brated as an artist, a CENTER FOP LEAR ll I IJ G teacher, and a scholar. His Lbook Findings expresses the joy he found in lifelong learning, and expounds his belief that the use of the arts in all aspects of education would instill that same joy in others. The Young People's Concerts were but one example of his teaching and scholarship. One of those concerts was devoted to celebrating teachers and the teaching profession. He said: "Teaching is probably the noblest profession in the world - the most unselfish, difficult, and hon orable profession. But it is also the most unappreciated, underrat Los Angeles. Devoted to improv There was an entrepreneurial ed, underpaid, and under-praised ing schools through the use of dimension from the start, with profession in the world." the arts, and driven by teacher each school using a few core leadership, the Center seeks to principles and local teachers Just before his death, Bernstein build the capacity in teachers and designing and customizing their established the Leonard Bernstein students to be a combination of local applications. That spirit Center for Learning Through the artist, teacher, and scholar. remains today. School teams went Arts, then in Nashville Tennessee. The early days in Nashville, their own way, collaborating That Center, and its incarnations were, from an educator's point of internally as well as with their along the way, has led to what is view, a splendid blend of rigorous own communities, to create better now a major educational reform research and talented expertise, schools using the "best practices" model, located within the with a solid reliance on teacher from within and from elsewhere. -

Tong Chen, Conductor

Tong Chen, conductor “Masterfully presented the Mendelssohn’s Fifth Symphony,” described the Leipzig Time. A prizewinner of the prestigious International Malko Conducting Competition, Tong Chen has quickly established herself as one of the most promising and exciting young conductors in her generation. Ms. Chen has worked with numerous orchestras across the globe, including Orquestra Sinfônica do Estado de São Paulo, Danish National Symphony Orchestra, Mikkelin Kaupunginorkesteri, Besançon Symphony Orchestra, Leipzig Symphony Orchestra, Bamberg Symphony Orchestra, Alabama Symphony Orchestra, Baltimore Symphony Orchestra, Charleston Symphony Orchestra, Richmond Symphony, Aspen Music Festival Orchestra, Manhattan School of Music Orchestra, Orchestra St. Luke’s, Peabody Symphony Orchestra, Xia Men Philharmonic, Qing Dao Symphony Orchestra, Guang Zhou Symphony Orchestra, and Shanghai Opera House, where she worked as the assistant Photo credit: Bob Plotkin conductor. 2019-2020 season’s highlight includes Tong’s debuts with New Jersey Symphony Orchestra, Shanghai Philharmonic, and Rutgers Symphony Orchestra; a return to Los Angeles Philharmonic working with Gustavo Dudamel and assisting Iván Fisher with Budapest Festival Orchestra at the Hollywood Bowl. This season marks her fifth anniversary as music director of Yonkers Philharmonic Orchestra. As an avid advocate of education, Chen taught orchestral conducting and led the orchestra program at Copland School of Music from 2012-2018. Summer 2019 marked her second years as the director of Queens College Conductor’s workshop, founded by Maurice Peress in 2010. Additionally, Tong is a regular guest conductor at Manhattan School of Music, Montclair State University, Manners Pre- college orchestra, and All-State Youth Orchestras in New York State area, as well as a guest lecturer at Shanghai Conservatory of Music. -

The Cliburn Names Marin Alsop As 2021 Jury Chairman

THE CLIBURN NAMES MARIN ALSOP AS 2021 JURY CHAIRMAN The American luminary will serve as jury chairman and Final Round conductor for the Sixteenth Van Cliburn International Piano Competition, May 28–June 12, 2021, at Bass Performance Hall in Fort Worth, Texas USA. Contact: Maggie Estes, director of communications and digital content, [email protected], 817.739.0459 FORT WORTH, Texas, March 28, 2019—The Cliburn announces today that Marin Alsop will be the jury chairman for the Sixteenth Van Cliburn International Piano Competition, taking place May 28–June 12, 2021, at Bass Performance Hall in Fort Worth, Texas USA. Widely considered one of the preeminent international music contests, the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition exists to share excellent classical music with the largest international audience possible and to launch the careers of its winners every four years. Building on a rich tradition that began with its 1962 origins in honor of Van Cliburn and his vision for using music to serve audiences and break down boundaries, the Cliburn seeks, with each edition, to achieve the highest artistic standards while utilizing contemporary tools to advance its reach. The world’s top 18- to 30-year-old pianists compete for gold in front of a live audience in Fort Worth, Texas, as well as a global online viewership of over 5 million. Beyond cash prizes, winning a Cliburn medal means comprehensive career management, concert tours, artistic support, and bolstered publicity efforts for the three years following. One of the world’s most distinguished and innovative conductors, Marin Alsop holds major appointments on three continents: music director of the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra since 2007; principal conductor and music director of the São Paulo State Symphony Orchestra since 2012; and chief conductor of the ORF Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra beginning September 2019. -

Marin Alsop La Dama De La Batuta

Entrevista Marin Alsop La dama de la batuta por Lorena Jiménez uando Marin Alsop (Nueva CYork, 1956), le anunció a su profesora de violín en la Juilliard Pre College Division que quería convertirse en directora de orquesta, ella le respondió: “Imposible, eres una niña”. Esa misma mañana, su padre (concertino del New York City Ballet) le regaló una caja de 10 batutas hechas a mano, que todavía conserva. “Fue su forma de decirme, puedes hacer lo que quieras, te apoyaremos”. Y Marin Alsop nunca renunció a su sueño; mientras se gana la vida como violinista freelance, comienza a estudiar dirección. No le resultó fácil encontrar una orquesta en el microcosmos masculino de la clásica y, apasionada del jazz y el swing, funda la orquesta Concordia con los miembros de su banda de jazz String Fever. A finales de los ochenta, se convierte en la primera mujer en recibir el famoso Premio de Dirección Koussevitzky del Tanglewood Music Center, donde fue alumna de su héroe y mentor Leonard Bernstein, el hombre que despertó su entusiasmo por la dirección cuando tenía 9 años y sus padres la llevaron a un concierto de la Filarmónica de Nueva York. “Eso es lo que quiero hacer”- dijo; inaccesible al desaliento, nunca cambió de idea, a pesar de que hasta mediados del siglo XX era raro que las orquestas contrataran mujeres instrumentistas y mucho menos directoras. “Tenía un poster de los Beatles en la pared de mi habitación, pero un poster más grande de Bernstein”. Hace poco más de una década, esta neoyorquina que irradia autoridad, pero con fama de dialogante con los músicos, a quien le gusta levantarse temprano, comenzar el día practicando cross trainer, y acompañando a su hijo a la escuela, hizo historia al convertirse en la primera mujer al frente de una de las principales orquestas americanas. -

Toscanini in Stereo a Report on RCA's "Electronic Reprocessing"

Toscanini in Stereo a report on RCA's "electronic reprocessing" MARCH ERS 60 CENTS FOR STEREO FANS! Three immortal recordings by Arturo Toscanini and the NBC Symphony have been given new tonal beauty and realism by means of a new RCA Victor engineering development, Electronic Stereo characteristics electronically, Reprocessing ( ESR ) . As a result of this technique, which creates stereo the Toscanini masterpieces emerge more moving, more impressive than ever before. With rigid supervision, all the artistic values have been scrupulously preserved. The performances are musically unaffected, but enhanced by the added spaciousness of ESR. Hear these historic Toscanini ESR albums at your dealer's soon. They cost no more than the original Toscanini monaural albums, which are still available. Note: ESR is for stereo phonographs only. A T ACTOR records, on the 33, newest idea in lei RACRO Or AMERICA Ask your dealer about Compact /1 CORPORATION M..00I sun.) . ., VINO .IMCMitmt Menem ILLCr sí1.10 ttitis I,M MT,oMC Mc0001.4 M , mi1MM MCRtmM M nm Simniind MOMSOMMC M Dvoìtk . Rn.psthI SYMPHONY Reemergáy Ravel RRntun. of Rome Plue. of Rome "FROM THE NEW WORLD" Pictures at an Exhibition TOSCANINI ARTURO TOSCANINI Toscanini NBC Symphony Orchestra Arturo It's all Empire -from the remarkable 208 belt- driven 3 -speed turntable -so quiet that only the sound of the music distinguishes between the turntable at rest and the turntable in motion ... to the famed Empire 98 transcription arm, so perfectly balanced that it will track a record with stylus forces well below those recommended by cartridge manufacturers. A. handsome matching walnut base is pro- vided. -

TMS 3-1 Pages Couleurs

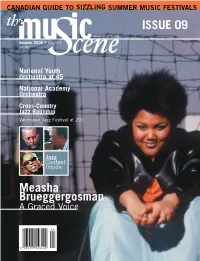

TMS3-4cover.5 2005-06-07 11:10 Page 1 CANADIAN GUIDE TO SIZZLING SUMMER MUSIC FESTIVALS ISSUE 09 www.scena.org Summer 2005 • Vol. 3.4 $4.95 National Youth Orchestra at 45 National Academy Orchestra Cross-Country Jazz Roundup Vancouver Jazz Festival at 20! Jazz Contest Inside Measha Brueggergosman A Graced Voice 0 4 0 0 6 5 3 8 5 0 4 6 4 4 9 TMS3-4 glossy 2005-06-06 09:14 Page 2 QUEEN ELISABETH COMPETITION 5 00 2 N I L O I V S. KHACHATRYAN with G. VARGA and the Belgian National Orchestra © Bruno Vessié 1st Prize Sergey KHACHATRYAN 2nd Prize Yossif IVANOV 3rd Prize Sophia JAFFÉ 4th Prize Saeka MATSUYAMA 5th Prize Mikhail OVRUTSKY 6th Prize Hyuk Joo KWUN Non-ranked laureates Alena BAEVA Andreas JANKE Keisuke OKAZAKI Antal SZALAI Kyoko YONEMOTO Dan ZHU Grand Prize of the Queen Elisabeth International Competition for Composers 2004: Javier TORRES MALDONADO Finalists Composition 2004: Kee-Yong CHONG, Paolo MARCHETTINI, Alexander MUNO & Myung-hoon PAK Laureate of the Queen Elisabeth Competition for Belgian Composers 2004: Hans SLUIJS WWW.QEIMC.BE QUEEN ELISABETH INTERNATIONAL MUSIC COMPETITION OF BELGIUM INFO: RUE AUX LAINES 20, B-1000 BRUSSELS (BELGIUM) TEL : +32 2 213 40 50 - FAX : +32 2 514 32 97 - [email protected] SRI_MusicScene 2005-06-06 10:20 Page 3 NEW RELEASES from the WORLD’S BEST LABELS Mahler Symphony No.9, Bach Cantatas for the feast San Francisco Symphony of St. John the Baptist Mendelssohn String Quartets, Orchestra, the Eroica Quartet Michael Tilson Thomas une 2005 marks the beginning of ATMA’s conducting.