Reading the Old Left in the Ewan Maccoll and Joan Littlewood's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joan Littlewood Education Pack in Association with Essentialdrama.Com Joan Littlewood Education Pack

in association with Essentialdrama.com Joan LittlEWOOD Education pack in association with Essentialdrama.com Joan Littlewood Education PAck Biography 2 Artistic INtentions 5 Key Collaborators 7 Influences 9 Context 11 Productions 14 Working Method 26 Text Phil Cleaves Nadine Holdsworth Theatre Recipe 29 Design Phil Cleaves Further Reading 30 Cover Image Credit PA Image Joan LIttlewood: Education pack 1 Biography Early Life of her life. Whilst at RADA she also had Joan Littlewood was born on 6th October continued success performing 1914 in South-West London. She was part Shakespeare. She won a prize for her of a working class family that were good at verse speaking and the judge of that school but they left at the age of twelve to competition, Archie Harding, cast her as get work. Joan was different, at twelve she Cleopatra in Scenes from Shakespeare received a scholarship to a local Catholic for BBC a overseas radio broadcast. That convent school. Her place at school meant proved to be one of the few successes that she didn't ft in with the rest of her during her time at RADA and after a term family, whilst her background left her as an she dropped out early in 1933. But the outsider at school. Despite being a misft, connection she made with Harding would Littlewood found her feet and discovered prove particularly infuential and life- her passion. She fell in love with the changing. theatre after a trip to see John Gielgud playing Hamlet at the Old Vic. Walking to Find Work Littlewood had enjoyed a summer in Paris It had me on the edge of my when she was sixteen and decided to seat all afternoon. -

ED024693.Pdf

DO CUMEN T R UM? ED 024 693 24 TE 001 061 By-Bogard. Travis. Ed. International Conference on Theatre Education and Development: A Report on the Conference Sponsored by AETA (State Department. Washington. D.C.. June 14-18. 1967). Spons Agency- American Educational Theatre Association. Washington. D.C.;Office of Education (DHEW). Washington. D.C. Bureau of Research. Bureau No- BR- 7-0783 Pub Date Aug 68 Grant- OEG- 1- 7-070783-1713 Note- I28p. Available from- AETA Executive Office. John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. 726 Jackson Place. N.V. Washington. D.C. (HC-$2.00). Journal Cit- Educational Theatre Journal; v20 n2A Aug 1968 Special Issue EDRS Price MF-$0.75 HC Not Available from EDRS. Descriptors-Acoustical Environment. Acting. Audiences. Auditoriums. Creative Dramatics. Drama. Dramatic Play. Dramatics. Education. Facilities. Fine Arts. Playwriting, Production Techniques. Speech. Speech Education. Theater Arts. Theaters The conference reported here was attended by educators and theater professionals from 24 countries, grouped into five discussion sections. Summaries of the proceedings of the discussion groups. each followed by postscripts by individual participants who wished to amplify portions of the summary. are presented. The discussion groups and the editors of their discussions are:"Training Theatre Personnel,Ralph Allen;"Theatre and Its Developing Audience," Francis Hodge; "Developing and Improving Artistic Leadership." Brooks McNamara; "Theatre in the Education Process." 0. G. Brockett; and "Improving Design for the Technical Function. Scenography. Structure and Function," Richard Schechner. A final section, "Soliloquies and Passages-at-Arms." containsselectedtranscriptions from audio tapes of portions of the conference. (JS) Educational Theatrejourna 1. -

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy in the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger 1939-1946 Valerie Wilson University College London PhD May 2001 ProQuest Number: U642581 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U642581 Published by ProQuest LLC(2015). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946 This thesis will examine the films planned or made by Powell and Pressburger in this period, with these aims: to demonstrate the way the contemporary realities of wartime Britain (political, social, cultural, economic) are represented in these films, and how the realities of British history (together with information supplied by the Ministry of Information and other government ministries) form the basis of much of their propaganda. to chart the changes in the stylistic combination of realism, naturalism, expressionism and surrealism, to show that all of these films are neither purely realist nor seamless products of artifice but carefully constructed narratives which use fantasy genres (spy stories, rural myths, futuristic utopias, dreams and hallucinations) to convey their message. -

The Ideal of Ensemble Practice in Twentieth-Century British Theatre, 1900-1968 Philippa Burt Goldsmiths, University of London P

The Ideal of Ensemble Practice in Twentieth-century British Theatre, 1900-1968 Philippa Burt Goldsmiths, University of London PhD January 2015 1 I hereby declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own and has not been and will not be submitted, in whole or in part, to any other university for the award of any other degree. Philippa Burt 2 Acknowledgements This thesis benefitted from the help, support and advice of a great number of people. First and foremost, I would like to thank Professor Maria Shevtsova for her tireless encouragement, support, faith, humour and wise counsel. Words cannot begin to express the depth of my gratitude to her. She has shaped my view of the theatre and my view of the world, and she has shown me the importance of maintaining one’s integrity at all costs. She has been an indispensable and inspirational guide throughout this process, and I am truly honoured to have her as a mentor, walking by my side on my journey into academia. The archival research at the centre of this thesis was made possible by the assistance, co-operation and generosity of staff at several libraries and institutions, including the V&A Archive at Blythe House, the Shakespeare Centre Library and Archive, the National Archives in Kew, the Fabian Archives at the London School of Economics, the National Theatre Archive and the Clive Barker Archive at Rose Bruford College. Dale Stinchcomb and Michael Gilmore were particularly helpful in providing me with remote access to invaluable material held at the Houghton Library, Harvard and the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas, Austin, respectively. -

Mick Evans Song List 1

MICK EVANS SONG LIST 1. 1927 If I could 2. 3 Doors Down Kryptonite Here Without You 3. 4 Non Blondes What’s Going On 4. Abba Dancing Queen 5. AC/DC Shook Me All Night Long Highway to Hell 6. Adel Find Another You 7. Allan Jackson Little Bitty Remember When 8. America Horse with No Name Sister Golden Hair 9. Australian Crawl Boys Light Up Reckless Oh No Not You Again 10. Angels She Keeps No Secrets from You MICK EVANS SONG LIST Am I Ever Gonna See Your Face Again 11. Avicii Hey Brother 12. Barenaked Ladies It’s All Been Done 13. Beatles Saw Her Standing There Hey Jude 14. Ben Harper Steam My Kisses 15. Bernard Fanning Song Bird 16. Billy Idol Rebel Yell 17. Billy Joel Piano Man 18. Blink 182 Small Things 19. Bob Dylan How Does It Feel 20. Bon Jovi Living on a Prayer Wanted Dead or Alive Always Bead of Roses Blaze of Glory Saturday Night MICK EVANS SONG LIST 21. Bruce Springsteen Dancing in the dark I’m on Fire My Home town The River Streets of Philadelphia 22. Bryan Adams Summer of 69 Heaven Run to You Cuts Like A Knife When You’re Gone 23. Bush Glycerine 24. Carly Simon Your So Vein 25. Cheap Trick The Flame 26. Choir Boys Run to Paradise 27. Cold Chisel Bow River Khe Sanh When the War is Over My Baby Flame Trees MICK EVANS SONG LIST 28. Cold Play Yellow 29. Collective Soul The World I know 30. Concrete Blonde Joey 31. -

A Discography of Robert Burns 1948 to 2002 Thomas Keith

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 33 | Issue 1 Article 30 2004 A Discography of Robert Burns 1948 to 2002 Thomas Keith Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Keith, Thomas (2004) "A Discography of Robert Burns 1948 to 2002," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 33: Iss. 1. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol33/iss1/30 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thomas Keith A Discography of Robert Bums 1948 to 2002 After Sir Walter Scott published his edition of border ballads he came to be chastised by the mother of James Hogg, one Margaret Laidlaw, who told him: "There was never ane 0 my sangs prentit till ye prentit them yoursel, and ye hae spoilt them awthegither. They were made for singing an no forreadin: butye hae broken the charm noo, and they'll never be sung mair.'l Mrs. Laidlaw was perhaps unaware that others had been printing Scottish songs from the oral tradition in great numbers for at least the previous hundred years in volumes such as Allan Ramsay's The Tea-Table Miscellany (1723-37), Orpheus Caledonius (1733) compiled by William Thompson, James Oswald's The Cale donian Pocket Companion (1743, 1759), Ancient and Modern Scottish Songs (1767, 1770) edited by David Herd, James Johnson's Scots Musical Museum (1787-1803) and A Select Collection of Original Scotish Airs (1793-1818) compiled by George Thompson-substantial contributions having been made to the latter two collections by Robert Burns. -

President's Letter

PRESIDENT’S LETTER October-November, 2020 Dear Friends, It may seem a little premature to extend our very best wishes to you now for the approaching holidays, Christmastime and the New Year. However, this has indeed been a strange year like no other. As this is the final Foundation Newsletter of 2020, it is our pleasure to wish you, our Friends, perhaps the earliest but warmest greetings for the forthcoming festive season. OUR HALLS ARE ALIVE WITH THE SOUNDS OF MUSIC Responding to the present urgent need for accessible and affordable teaching, coaching and rehearsal space, the Foundation continues to make the Seaborn Library, with its grand piano and suitable acoustic, available to performing artists. As mentioned in the last Newsletter, Les Solomon's riveting production of The Cradeaux Canvas rehearsed in our Library and then opened successfully in the El Rocco Theatre Room in Kings Cross to claim the title of the first production to open Sydney theatres after the COVID closures. Those of us who attended a special benefit night for the ABF’s ACTober, were impressed by the actors’ compelling performances - and safety protocols. One reviewer noted the performance was ‘safer than the supermarket’. Other theatres are now gradually and tentatively reopening. Similarly, Eugene Lynch and his cast, pictured elsewhere in this Newsletter, after rehearsing in our Library, presented the first opera since the venue shutdown. Their short season of the Australian opera Love Burns at the East Sydney Community & Arts Centre, also presented according to safety guidelines, revealed the exciting emergence of a new generation of brilliant young talent. -

Bolderboulder 10K Results

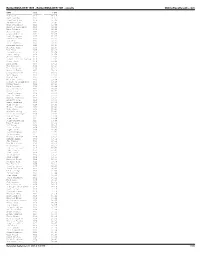

BolderBOULDER 1986 - BolderBOULDER 10K - results OnlineRaceResults.com NAME DIV TIME ---------------------- ------- ----------- Jon Luff M18 31:14 Jeff Sanchez M20 31:23 Jonathan Hume M18 31:58 Ed Ostrovich M27 32:04 Mark Stromberg M21 32:09 Michael Velasquez M16 32:21 Rick Renfrom M32 32:22 James Ysebaert M22 32:24 Louis Anderson M32 32:25 Joel Thompson M27 32:27 Kevin Collins M31 32:34 Rob Welo M22 32:42 Bill Lawrance M31 32:44 Richard Bishop M28 32:45 Chester Carl M33 32:47 Bob Fink M29 32:51 David Couture M18 32:54 Brent Terry M24 32:58 Chris Nelson M16 33:02 Robert III Hillgrove M18 33:05 Steve Smith M16 33:08 Rick Katz M37 33:11 Tom Donohoue M30 33:14 Dale Garland M28 33:17 Michael Tobin M22 33:18 Craig Marshall M28 33:20 Mark Weeks M34 33:21 Sam Wolfe M27 33:23 William Levine M25 33:26 Robert Jr Dominguez M30 33:26 David Teague M32 33:28 Alex Accetta M16 33:29 Dave Dreikosen M32 33:31 Peter Boes M22 33:32 Daniel Bieser M24 33:32 Matt Strand M18 33:33 George Frushour M23 33:34 Everett Bear M16 33:35 Bruce Pulford M31 33:36 Jeff Stein M26 33:40 Thomas Teschner M22 33:42 Mike Chase M28 33:43 Michael Junig M21 33:43 Parrick Carrigan M26 33:44 Jay Kirksey M30 33:46 Todd Moore M22 33:49 Jerry Duckworth M24 33:49 Rick Reimer M37 33:50 RaY Keogh M28 33:50 Dave Dooley M39 33:50 Roger Innes M26 33:50 David Chipman M22 33:51 Brian Boehm M17 33:51 Michael Dunlap M29 33:51 Arthur Mizzi M30 33:52 Jim Tanner M18 33:52 Bob Hillgrove M41 33:52 Ramon Duran M18 33:52 Ken Jr. -

A Lively Theatre There's a Revolution Afoot in Theatre Design, Believes

A LIVELY THEatRE There’s a revolution afoot in theatre design, believes architectural consultant RICHARD PILBROW, that takes its cue from the three-dimensional spaces of centuries past The 20th century has not been a good time for theatre architecture. In the years from the 1920s to the 1970s, the world became littered with overlarge, often fan-shaped auditoriums that are barren in feeling and lacking in intimacy--places that are seldom conducive to that interplay between actor and audience that lies at the heart of the theatre experience. Why do theatres of the 19th century feel so much more “theatrical”? And why do so many actors and audiences prefer the old to the new? More generally, does theatre architecture really matter? There are some that believe that as soon as the house lights dim, the audience only needs to see and hear what happens on the stage. Perhaps audiences don’t hiss, boo and shout during a performance any more, but most actors and directors know that an audience’s reaction critically affects the performance. The nature of the theatre space, the configuration of the audience and the intimacy engendered by the form of the auditorium can powerfully assist in the formation of that reaction. A theatre auditorium may be a dead space or a lively one. Theatres designed like cinemas or lecture halls can lay a dead hand on the theatre experience. Happily, the past 20 years have seen a revolution in attitude to theatre design. No longer is a theatre only a place for listening or viewing. -

1998 Acquisitions

1998 Acquisitions PAINTINGS PRINTS Carl Rice Embrey, Shells, 1972. Acrylic on panel, 47 7/8 x 71 7/8 in. Albert Belleroche, Rêverie, 1903. Lithograph, image 13 3/4 x Museum purchase with funds from Charline and Red McCombs, 17 1/4 in. Museum purchase, 1998.5. 1998.3. Henry Caro-Delvaille, Maternité, ca.1905. Lithograph, Ernest Lawson, Harbor in Winter, ca. 1908. Oil on canvas, image 22 x 17 1/4 in. Museum purchase, 1998.6. 24 1/4 x 29 1/2 in. Bequest of Gloria and Dan Oppenheimer, Honoré Daumier, Ne vous y frottez pas (Don’t Meddle With It), 1834. 1998.10. Lithograph, image 13 1/4 x 17 3/4 in. Museum purchase in memory Bill Reily, Variations on a Xuande Bowl, 1959. Oil on canvas, of Alexander J. Oppenheimer, 1998.23. 70 1/2 x 54 in. Gift of Maryanne MacGuarin Leeper in memory of Marsden Hartley, Apples in a Basket, 1923. Lithograph, image Blanche and John Palmer Leeper, 1998.21. 13 1/2 x 18 1/2 in. Museum purchase in memory of Alexander J. Kent Rush, Untitled, 1978. Collage with acrylic, charcoal, and Oppenheimer, 1998.24. graphite on panel, 67 x 48 in. Gift of Jane and Arthur Stieren, Maximilian Kurzweil, Der Polster (The Pillow), ca.1903. 1998.9. Woodcut, image 11 1/4 x 10 1/4 in. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Frederic J. SCULPTURE Oppenheimer in memory of Alexander J. Oppenheimer, 1998.4. Pierre-Jean David d’Angers, Philopoemen, 1837. Gilded bronze, Louis LeGrand, The End, ca.1887. Two etching and aquatints, 19 in. -

Talking Theatre Extract

Richard Eyre TALKING THEATRE Interviews with Theatre People Contents Introduction xiii Interviews John Gielgud 1 Peter Brook 16 Margaret ‘Percy’ Harris 29 Peter Hall 35 Ian McKellen 52 Judi Dench 57 Trevor Nunn 62 Vanessa Redgrave 67 NICK HERN BOOKS Fiona Shaw 71 London Liam Neeson 80 www.nickhernbooks.co.uk Stephen Rea 87 ix RICHARD EYRE CONTENTS Stephen Sondheim 94 Steven Berkoff 286 Arthur Laurents 102 Willem Dafoe 291 Arthur Miller 114 Deborah Warner 297 August Wilson 128 Simon McBurney 302 Jason Robards 134 Robert Lepage 306 Kim Hunter 139 Appendix Tony Kushner 144 John Johnston 313 Luise Rainer 154 Alan Bennett 161 Index 321 Harold Pinter 168 Tom Stoppard 178 David Hare 183 Jocelyn Herbert 192 William Gaskill 200 Arnold Wesker 211 Peter Gill 218 Christopher Hampton 225 Peter Shaffer 232 Frith Banbury 239 Alan Ayckbourn 248 John Bury 253 Victor Spinetti 259 John McGrath 266 Cameron Mackintosh 276 Patrick Marber 280 x xi JOHN GIELGUD Would you say the real father—or mother—of the National Theatre and the Royal Shakespeare Company is Lilian Baylis? Well, I think she didn’t know her arse from her elbow. She was an extraordinary old woman, really. And I never knew anybody who knew her really well. The books are quite good about her, but except for her eccentricities there’s nothing about her professional appreciation of Shakespeare. She had this faith which led her to the people she needed. Did she choose the actors? I don’t think so. She chose the directors. John Gielgud Yes, she had a very difficult time with them. -

Mckinney Macartney Management Ltd

McKinney Macartney Management Ltd MICK COULTER BSC - Director of Photography NASTY WOMEN (Feature Film) Director: Chris Addison. Producer: Roger Birnbaum and Rebel Wilson. Starring: Anne Hathaway and Rebel Wilson. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. SHETLAND (Series 4) Director: Rebecca Gatward. Producer: Eric Coulter. Starring: Douglas Henshall, Stephen Robertson and Alison O’Donnell. BBC Scotland. THE ESCAPE Director: Paul J. Franklin. Producers: Jessica Malik and Jessica Parker. Starring: Art Malik, Ben Miller and Olivia Williams. Parri Passu Films. BITCH aka SUKA Director: Krzysztof Lang. Producers: Wojciech Pałys and Mariusz Łukomski. Starring: Olga Bołądź, Piotr Adamczyk, Marieta Żukowska, Marcin Korcz Katarzyna Figura, Piotr Głowacki and Marian Dziędziel. Monolith Films. MALEFICENT (UK shoot) Director: Robert Stromberg. Producer: Don Hahn, Scott Michael Murray and Joe Roth. Starring: Angelina Jolie, Elle Fanning, Juno Temple, Sharito Copley and Imelda Staunton. Moving Picture Company / Walt Disney Pictures. SINGULARITY (UK shoot) Director: Roland Joffé. Producer: Paul Breuls, Guy Louthan and Ajey Jhankar. Starring Josh Hartnett, Bipasha Basu, Claire van der Boom, Billie Brown and James Mackay. Corsan NV. THE BANK JOB Director: Roger Donaldson. Producers: Steven Chasman and Charles Rosen. Starring: Jason Statham, Saffron Burrows, Stephen Campbell Moore and David Suchet. Skyline Productions. Gable House, 18 – 24 Turnham Green Terrace, London W4 1QP Tel: 020 8995 4747 Fax: 020 8995 2414 E-mail: [email protected] www.mckinneymacartney.com VAT Reg. No: 685 1851 06 MICK COULTER Contd … 2 LOVE ACTUALLY Director: Richard Curtis. Producers: Duncan Kenworthy, Tim Bevan and Eric Fellner. Starring: Alan Rickman, Hugh Grant, Liam Neeson, Bill Nighy, Colin Firth Emma Thompson, Laura Linney, Martine McCutcheon and Rowan Atkinson.