Chronic Venous Insufficiency and Varicose Veins of the Lower Extremities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clinical Study Is Nonmicronized Diosmin 600Mg As Effective As

Hindawi International Journal of Vascular Medicine Volume 2020, Article ID 4237204, 9 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/4237204 Clinical Study Is Nonmicronized Diosmin 600mg as Effective as Micronized Diosmin 900mg plus Hesperidin 100mg on Chronic Venous Disease Symptoms? Results of a Noninferiority Study Marcio Steinbruch,1 Carlos Nunes,2 Romualdo Gama,3 Renato Kaufman,4 Gustavo Gama,5 Mendel Suchmacher Neto,6 Rafael Nigri,7 Natasha Cytrynbaum,8 Lisa Brauer Oliveira,9 Isabelle Bertaina,10 François Verrière,10 and Mauro Geller 3,6,9 1Hospital Albert Einstein (São Paulo-Brasil), R. Mauricio F Klabin 357/17, Vila Mariana, SP, Brazil 04120-020 2Instituto de Pós-Graduação Médica Carlos Chagas-Fundação Educacional Serra dos Órgãos-UNIFESO (Rio de Janeiro/Teresópolis- Brasil), Av. Alberto Torres 111, Teresópolis, RJ, Brazil 25964-004 3Fundação Educacional Serra dos Órgãos-UNIFESO (Teresópolis-Brasil), Av. Alberto Torres 111, Teresópolis, RJ, Brazil 25964-004 4Faculdade de Ciências Médicas, Universidade Estadual do Rio de Janeiro (UERJ) (Rio de Janeiro-Brazil), Av. N. Sra. De Copacapana, 664/206, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil 22050-903 5Fundação Educacional Serra dos Órgãos-UNIFESO (Teresópolis-Brasil), Rua Prefeito Sebastião Teixeira 400/504-1, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil 25953-200 6Instituto de Pós-Graduação Médica Carlos Chagas (Rio de Janeiro-Brazil), R. General Canabarro 68/902, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil 20271-200 7Department of Medicine, Rutgers New Jersey Medical School-USA, 185 S Orange Ave., Newark, NJ 07103, USA 8Hospital Universitário Pedro Ernesto, Universidade Estadual do Rio de Janeiro (UERJ) (Rio de Janeiro-Brazil), R. Hilário de Gouveia, 87/801, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil 22040-020 9Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) (Rio de Janeiro-Brazil), Av. -

Corona Mortis: the Abnormal Obturator Vessels in Filipino Cadavers

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Corona Mortis: the Abnormal Obturator Vessels in Filipino Cadavers Imelda A. Luna Department of Anatomy, College of Medicine, University of the Philippines Manila ABSTRACT Objectives. This is a descriptive study to determine the origin of abnormal obturator arteries, the drainage of abnormal obturator veins, and if any anastomoses exist between these abnormal vessels in Filipino cadavers. Methods. A total of 54 cadaver halves, 50 dissected by UP medical students and 4 by UP Dentistry students were included in this survey. Results. Results showed the abnormal obturator arteries arising from the inferior epigastric arteries in 7 halves (12.96%) and the abnormal communicating veins draining into the inferior epigastric or external iliac veins in 16 (29.62%). There were also arterial anastomoses in 5 (9.25%) with the inferior epigastric artery, and venous anastomoses in 16 (29.62%) with the inferior epigastric or external iliac veins. Bilateral abnormalities were noted in a total 6 cadavers, 3 with both arterial and venous, and the remaining 3 with only venous anastomoses. Conclusion. It is important to be aware of the presence of these abnormalities that if found during surgery, must first be ligated to avoid intraoperative bleeding complications. Key Words: obturator vessels, abnormal, corona mortis INtroDUCTION The main artery to the pelvic region is the internal iliac artery (IIA) with two exceptions: the ovarian/testicular artery arises directly from the aorta and the superior rectal artery from the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA). The internal iliac or hypogastric artery is one of the most variable arterial systems of the human body, its parietal branches, particularly the obturator artery (OBA) accounts for most of its variability. -

The Benefits of Flavonoids in Diabetic Retinopathy

nutrients Review The Benefits of Flavonoids in Diabetic Retinopathy 1, 1, 2,3,4,5 1,2,3,4, Ana L. Matos y, Diogo F. Bruno y, António F. Ambrósio and Paulo F. Santos * 1 Department of Life Sciences, University of Coimbra, Calçada Martim de Freitas, 3000-456 Coimbra, Portugal; [email protected] (A.L.M.); [email protected] (D.F.B.) 2 Coimbra Institute for Clinical and Biomedical Research (iCBR), Faculty of Medicine, University of Coimbra, 3000-548 Coimbra, Portugal; [email protected] 3 Center for Innovative Biomedicine and Biotechnology (CIBB), University of Coimbra, 3000-548 Coimbra, Portugal 4 Clinical Academic Center of Coimbra (CACC), 3004-561 Coimbra, Portugal 5 Association for Innovation and Biomedical Research on Light and Image (AIBILI), 3000-548 Coimbra, Portugal * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +351-239-240-762 These authors contributed equally to the work. y Received: 10 September 2020; Accepted: 13 October 2020; Published: 16 October 2020 Abstract: Diabetic retinopathy (DR), one of the most common complications of diabetes, is the leading cause of legal blindness among adults of working age in developed countries. After 20 years of diabetes, almost all patients suffering from type I diabetes mellitus and about 60% of type II diabetics have DR. Several studies have tried to identify drugs and therapies to treat DR though little attention has been given to flavonoids, one type of polyphenols, which can be found in high levels mainly in fruits and vegetables, but also in other foods such as grains, cocoa, green tea or even in red wine. -

Vessels and Circulation

CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM OUTLINE 23.1 Anatomy of Blood Vessels 684 23.1a Blood Vessel Tunics 684 23.1b Arteries 685 23.1c Capillaries 688 23 23.1d Veins 689 23.2 Blood Pressure 691 23.3 Systemic Circulation 692 Vessels and 23.3a General Arterial Flow Out of the Heart 693 23.3b General Venous Return to the Heart 693 23.3c Blood Flow Through the Head and Neck 693 23.3d Blood Flow Through the Thoracic and Abdominal Walls 697 23.3e Blood Flow Through the Thoracic Organs 700 Circulation 23.3f Blood Flow Through the Gastrointestinal Tract 701 23.3g Blood Flow Through the Posterior Abdominal Organs, Pelvis, and Perineum 705 23.3h Blood Flow Through the Upper Limb 705 23.3i Blood Flow Through the Lower Limb 709 23.4 Pulmonary Circulation 712 23.5 Review of Heart, Systemic, and Pulmonary Circulation 714 23.6 Aging and the Cardiovascular System 715 23.7 Blood Vessel Development 716 23.7a Artery Development 716 23.7b Vein Development 717 23.7c Comparison of Fetal and Postnatal Circulation 718 MODULE 9: CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM mck78097_ch23_683-723.indd 683 2/14/11 4:31 PM 684 Chapter Twenty-Three Vessels and Circulation lood vessels are analogous to highways—they are an efficient larger as they merge and come closer to the heart. The site where B mode of transport for oxygen, carbon dioxide, nutrients, hor- two or more arteries (or two or more veins) converge to supply the mones, and waste products to and from body tissues. The heart is same body region is called an anastomosis (ă-nas ′tō -mō′ sis; pl., the mechanical pump that propels the blood through the vessels. -

Chondroprotective Agents

Europaisches Patentamt J European Patent Office © Publication number: 0 633 022 A2 Office europeen des brevets EUROPEAN PATENT APPLICATION © Application number: 94109872.5 © Int. CI.6: A61K 31/365, A61 K 31/70 @ Date of filing: 27.06.94 © Priority: 09.07.93 JP 194182/93 Saitama 350-02 (JP) Inventor: Niimura, Koichi @ Date of publication of application: Rune Warabi 1-718, 11.01.95 Bulletin 95/02 1-17-30, Chuo Warabi-shi, 0 Designated Contracting States: Saitama 335 (JP) CH DE FR GB IT LI SE Inventor: Umekawa, Kiyonori 5-4-309, Mihama © Applicant: KUREHA CHEMICAL INDUSTRY CO., Urayasu-shi, LTD. Chiba 279 (JP) 9-11, Horidome-cho, 1-chome Nihonbashi Chuo-ku © Representative: Minderop, Ralph H. Dr. rer.nat. Tokyo 103 (JP) et al Cohausz & Florack @ Inventor: Watanabe, Koju Patentanwalte 2-5-7, Tsurumai Bergiusstrasse 2 b Sakado-shi, D-30655 Hannover (DE) © Chondroprotective agents. © A chondroprotective agent comprising a flavonoid compound of the general formula (I): (I) CM < CM CM wherein R1 to R9 are, independently, a hydrogen atom, hydroxyl group, or methoxyl group and X is a single bond or a double bond, or a stereoisomer thereof, or a naturally occurring glycoside thereof is disclosed. The 00 00 above compound strongly inhibits proteoglycan depletion from the chondrocyte matrix and exhibits a function to (Q protect cartilage, and thus, is extremely effective for the treatment of arthropathy. Rank Xerox (UK) Business Services (3. 10/3.09/3.3.4) EP 0 633 022 A2 BACKGROUND OF THE INVENTION 1 . Field of the Invention 5 The present invention relates to an agent for protecting cartilage, i.e., a chondroprotective agent, more particularly, a chondroprotective agent containing a flavonoid compound or a stereoisomer thereof, or a naturally occurring glycoside thereof. -

Vein Disease: Your Personal Prevention Programme While Your

Vein disease: Your personal prevention programme While your arteries transport blood containing oxygen and nutrients to the body cells, the veins are responsible for taking ‘used’ blood via the heart back to the lungs, where it can be enriched with fresh oxygen. In order for blood to be returned to the heart against the force of gravity, the vein valves must close tightly and the tissue which surrounds the veins must be strong. Otherwise the veins expand and become varicose. There’s a danger of thromboses, emboli and so-called ‘open leg’ ulcers. Self-diagnosis Spider-bursts (left) and reticular veins (right) are changes in the blood vessels which can be early signs of vein disease. Varicose veins (left and right) should be treated, if necessary surgically, as soon as possible. Deep vein thrombosis (left) is highly dangerous: You must seek treatment immediately! If you have vasculitis (inflammation of the vein wall - right) you should also visit a doctor or specialist clinic without delay. The classic symptoms of vein disease are swollen legs, pins and needles and feelings of tension in the calves, foot and calf cramps, legs which feel heavy or tired in the evening. Standing the whole day or frequent flying put a special burden on the vein system of the legs. © heigel.com www.heigel.com These things are good for your veins: Take frequent long walks as this exercises the leg and foot musculature. Sports involving sustained activity, such as hiking, swimming, jogging, skiing, dancing, cycling and gymnastics, are especially recommended. Whenever you are involved in an activity which involves sitting or standing, take every opportunity which presents itself to walk around. -

Association Between Hemorrhoids and Lower Extremity Chronic Venous Insufficiency

Open Access Original Article DOI: 10.7759/cureus.4502 Association Between Hemorrhoids and Lower Extremity Chronic Venous Insufficiency Ugur Ekici 1 , Abdulcabbar Kartal 2 , Murat F. Ferhatoglu 2 1. General Surgery, Istanbul Gelişim University, Istanbul, TUR 2. General Surgery, Okan University Medical Faculty, Istanbul, TUR Corresponding author: Abdulcabbar Kartal, [email protected] Disclosures can be found in Additional Information at the end of the article Abstract Aim The aim of the present study was to evaluate the incidence of varicose veins among patients with hemorrhoidal disease and to compare its incidence reported in various community-based studies. Method The study group comprised of 100 patients who underwent surgery for symptomatic internal or external hemorrhoids; the control group consisted of 100 volunteers who received no prior therapy for hemorrhoidal disease and lacked any symptoms or findings suggestive of this condition. Subjects in both the groups were inquired with respect to their demographic data and risk factors. Both groups were asked to stand for two minutes before performing leg examinations while still in the standing position. The findings were recorded for both the groups. Varicose veins were classified according to the clinical appearance section of the Clinical, Etiologic, Anatomic, and Pathophysiologic (CEAP) classification that was developed by the 1994 American Venous Forum. Results There was no significant difference between the two groups with respect to age and body mass index (BMI). Significant relationships were identified between the groups with respect to the incidence of varicose veins and chronic constipation. The incidence of C1 and C2 varicose veins observed in the study group was higher than that observed in the control group. -

Musculoskeletal Clinical Vignettes a Case Based Text

Leading the world to better health MUSCULOSKELETAL CLINICAL VIGNETTES A CASE BASED TEXT Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, RCSI Department of General Practice, RCSI Department of Rheumatology, Beaumont Hospital O’Byrne J, Downey R, Feeley R, Kelly M, Tiedt L, O’Byrne J, Murphy M, Stuart E, Kearns G. (2019) Musculoskeletal clinical vignettes: a case based text. Dublin, Ireland: RCSI. ISBN: 978-0-9926911-8-9 Image attribution: istock.com/mashuk CC Licence by NC-SA MUSCULOSKELETAL CLINICAL VIGNETTES Incorporating history, examination, investigations and management of commonly presenting musculoskeletal conditions 1131 Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, RCSI Prof. John O'Byrne Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, RCSI Dr. Richie Downey Prof. John O'Byrne Mr. Iain Feeley Dr. Richie Downey Dr. Martin Kelly Mr. Iain Feeley Dr. Lauren Tiedt Dr. Martin Kelly Department of General Practice, RCSI Dr. Lauren Tiedt Dr. Mark Murphy Department of General Practice, RCSI Dr Ellen Stuart Dr. Mark Murphy Department of Rheumatology, Beaumont Hospital Dr Ellen Stuart Dr Grainne Kearns Department of Rheumatology, Beaumont Hospital Dr Grainne Kearns 2 2 Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, RCSI Prof. John O'Byrne Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, RCSI Dr. Richie Downey TABLE OF CONTENTS Prof. John O'Byrne Mr. Iain Feeley Introduction ............................................................. 5 Dr. Richie Downey Dr. Martin Kelly General guidelines for musculoskeletal physical Mr. Iain Feeley examination of all joints .................................................. 6 Dr. Lauren Tiedt Dr. Martin Kelly Upper limb ............................................................. 10 Department of General Practice, RCSI Example of an upper limb joint examination ................. 11 Dr. Lauren Tiedt Shoulder osteoarthritis ................................................. 13 Dr. Mark Murphy Adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder) ............................ 16 Department of General Practice, RCSI Dr Ellen Stuart Shoulder rotator cuff pathology ................................... -

16441-16455 Page 16441 S

S. Umamaheswari*et al. /International Journal of Pharmacy & Technology ISSN: 0975-766X CODEN: IJPTFI Available Online through Research Article www.ijptonline.com EFFECT OF FLAVONOIDS DIOSMIN, MORIN AND CHRYSIN ON CHANG LIVER CELL LINE K.S. Sridevi Sangeetha1, S. Umamaheswari1*, C. Uma Maheswara Reddy1, S. Narayana kalkura2 1 Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Pharmacy, Sri Ramachandra University, Porur, Chennai 2Crystal Growth Centre, Anna University, Guindy, Chennai. Email: [email protected] Received on 06-08-2016 Accepted on 27-08-2016 Abstract Objective: To evaluate the effect of selected flavonoids diosmin, morin and chrysin on chang cell (normal human liver cells) line by using cell viability assay. Methods: The cell viability assay on chang cell was determined using MTT (3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazolyl-2)-2, 5- diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay. Diosmin, morin and chrysin were subjected in the concentration of 1.625 µM, 3.125 µM, 6.25 µM, 12.5 µM, 25 µM, 50 µM, 100 µM and 500 µM respectively. Results: The cytoprotective activity by MTT method showed that the IC 50 value of diosmin, morin and chrysin was 101.91 µM, 14.62 µM and 70.00 µM respectively. Conclusion: Out of the three flavonoids, diosmin and chrysin were proven to have very good cytoprotective activity against Chang cell line. The order of activity was found to be Disomin > Chrysin > Morin. Key words: Flavonoid, Chang cell line, Diosmin, Morin, Chrysin Introduction Plant produces different types of secondary metabolites and one such group is flavonoid. They are polyphenolic in nature and present in different part of the plant like leaves, flowers, fruits, vegetable etc. -

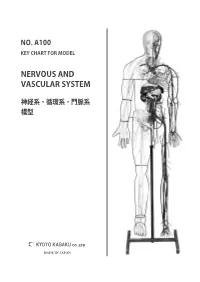

Nervous and Vascular System

NO. A100 KEY CHART FOR MODEL NERVOUS AND VASCULAR SYSTEM 神経系・循環系・門脈系 模型 MADE IN JAPAN KEY CHART FOR MODEL NO. A100 NERVOUS AND VASCULAR SYSTEM 神経系・循環系・門脈系模型 White labels BRAIN ENCEPHALON 脳 A.Frontal lobe of cerebrum A. Lobus frontalis A. 前頭葉 1. Marginal gyrus 1. Gyrus frontalis superior 1. 上前頭回 2. Middle frontal gyrus 2. Gyrus frontalis medius 2. 中前頭回 3. Inferior frontal gyrus 3. Gyrus frontalis inferior 3. 下前頭回 4. Precentral gyru 4. Gyrus precentralis 4. 中心前回 B. Parietal lobe of cerebrum B. Lobus parietalis B. 全頂葉 5. Postcentral gyrus 5. Gyrus postcentralis 5. 中心後回 6. Superior parietal lobule 6. Lobulus parietalis superior 6. 上頭頂小葉 7. Inferior parietal lobule 7. Lobulus parietalis inferior 7. 下頭頂小葉 C.Occipital lobe of cerebrum C. Lobus occipitalis C. 後頭葉 D. Temporal lobe D. Lobus temporalis D. 側頭葉 8. Superior temporal gyrus 8. Gyrus temporalis superior 8. 上側頭回 9. Middle temporal gyrus 9. Gyrus temporalis medius 9. 中側頭回 10. Inferior temporal gyrus 10. Gyrus temporalis inferior 10. 下側頭回 11. Lateral sulcus 11. Sulcus lateralis 11. 外側溝(外側大脳裂) E. Cerebellum E. Cerebellum E. 小脳 12. Biventer lobule 12. Lobulus biventer 12. 二腹小葉 13. Superior semilunar lobule 13. Lobulus semilunaris superior 13. 上半月小葉 14. Inferior lobulus semilunaris 14. Lobulus semilunaris inferior 14. 下半月小葉 15. Tonsil of cerebellum 15. Tonsilla cerebelli 15. 小脳扁桃 16. Floccule 16. Flocculus 16. 片葉 F.Pons F. Pons F. 橋 G.Medullary G. Medulla oblongata G. 延髄 SPINAL CORD MEDULLA SPINALIS 脊髄 H. Cervical enlargement H.Intumescentia cervicalis H. 頸膨大 I.Lumbosacral enlargement I. Intumescentia lumbalis I. 腰膨大 J.Cauda equina J. -

Varicose Veins

Varicose Veins: Diagnosis and Treatment Jaqueline Raetz, MD; Megan Wilson, MD; and Kimberly Collins, MD University of Washington Family Medicine Residency, Seattle, Washington Varicose veins are twisted, dilated veins most commonly located on the lower extremities. The exact pathophysiology is debated, but it involves a genetic predisposition, incompetent valves, weakened vascular walls, and increased intravenous pressure. Risk factors include family history of venous disease; female sex; older age; chronically increased intra-abdominal pressure due to obesity, preg- nancy, chronic constipation, or a tumor; and prolonged standing. Symptoms of varicose veins include a heavy, achy feeling and an itching or burning sensation; these symptoms worsen with prolonged standing. Potential complications include infection, leg ulcers, stasis changes, and thrombosis. Con- servative treatment options include external compression; lifestyle modifications, such as avoidance of prolonged standing and straining, exercise, wearing nonrestrictive clothing, modification of car- diovascular risk factors, and interventions to reduce peripheral edema; elevation of the affected leg; weight loss; and medical therapy. There is not enough evidence to determine if compression stock- ings are effective in the treatment of varicose veins in the absence of active or healed venous ulcers. Interventional treatments include external laser thermal ablation, endovenous thermal ablation, endo- venous sclerotherapy, and surgery. Although surgery was once the standard of care, it largely has been replaced by endovenous thermal ablation, which can be performed under local anesthesia and may have better outcomes and fewer complications than other treatments. Existing evidence and clinical guidelines suggest that a trial of compression therapy is not warranted before referral for endove- nous thermal ablation, although it may be necessary for insurance coverage. -

Varicose Veins and Superficial Thrombophlebitis

ENTITLEMENT ELIGIBILITY GUIDELINES VARICOSE VEINS AND SUPERFICIAL THROMBOPHLEBITIS 1. VARICOSE VEINS MPC 00727 ICD-9 454 DEFINITION Varicose Veins of the lower extremities are a dilatation, lengthening and tortuosity of a subcutaneous superficial vein or veins of the lower extremity such as the saphenous veins and perforating veins. A diagnosis of varicose veins is sometimes made in error when the veins are prominent but neither varicose or abnormal. This guideline excludes Deep Vein Thrombosis, and telangiectasis. DIAGNOSTIC STANDARD Diagnosis by a qualified medical practitioner is required. ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY The venous system of the lower extremities consists of: 1. The deep system of veins. 2. The superficial veins’ system. 3. The communicating (or perforating) veins which connect the first two systems. There are primary and secondary causes of varicose veins. Primary causes are congenital and/or may develop from inherited conditions. Secondary causes generally result from factors other than congenital factors. VETERANS AFFAIRS CANADA FEBRUARY 2005 Entitlement Eligibility Guidelines - VARICOSE VEINS/SUPERFICIAL THROMBOPHLEBITIS Page 2 CLINICAL FEATURES Clinical onset usually takes place when varicosities in the affected leg or legs appear. Varicosities typically present as a bluish discolouration and may have a raised appearance. The affected limb may also demonstrate the following: • Aching • Discolouration • Inflammation • Swelling • Heaviness • Cramps Varicose Veins may be large and apparent or quite small and barely discernible. Aggravation for the purposes of Varicose Veins may be represented by the veins permanently becoming larger or more extensive, or a need for operative intervention, or the development of Superficial Thrombophlebitis. PENSION CONSIDERATIONS A. CAUSES AND/OR AGGRAVATION THE TIMELINES CITED BELOW ARE NOT BINDING.