Law in Comics and Graphic Novels Article 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why No Wonder Woman?

Why No Wonder Woman? A REPORT ON THE HISTORY OF WONDER WOMAN AND A CALL TO ACTION!! Created for Wonder Woman Fans Everywhere Introduction by Jacki Zehner with Report Written by Laura Moore April 15th, 2013 Wonder Woman - p. 2 April 15th, 2013 AN INTRODUCTION AND FRAMING “The destiny of the world is determined less by battles that are lost and won than by the stories it loves and believes in” – Harold Goddard. I believe in the story of Wonder Woman. I always have. Not the literal baby being made from clay story, but the metaphorical one. I believe in a story where a woman is the hero and not the victim. I believe in a story where a woman is strong and not weak. Where a woman can fall in love with a man, but she doesnʼt need a man. Where a woman can stand on her own two feet. And above all else, I believe in a story where a woman has superpowers that she uses to help others, and yes, I believe that a woman can help save the world. “Wonder Woman was created as a distinctly feminist role model whose mission was to bring the Amazon ideals of love, peace, and sexual equality to ʻa world torn by the hatred of men.ʼ”1 While the story of Wonder Woman began back in 1941, I did not discover her until much later, and my introduction didnʼt come at the hands of comic books. Instead, when I was a little girl I used to watch the television show starring Lynda Carter, and the animated television series, Super Friends. -

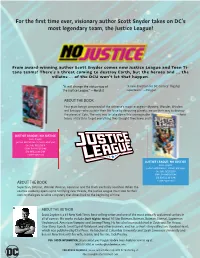

For the First Time Ever, Visionary Author Scott Snyder Takes on DC's Most

For the first time ever, visionary author Scott Snyder takes on DC’s most legendary team, the Justice League! From award-winning author Scott Snyder comes new Justice League and Teen Ti- tans teams! There’s a threat coming to destroy Earth, but the heroes and ... the villains ... of the DCU won’t let that happen. “It will change the status-quo of “A new direction for DC Comics’ flagship the Justice League.” —Nerdist superteam.” —Polygon ABOUT THE BOOK Four giant beings comprised of the universe’s major energies—Mystery, Wonder, Wisdom and Entropy—who sustain their life force by devouring planets, are on their way to destroy the planet of Colu. The only way to take down this unimaginable threat is for the superhero teams of Earth to forget everything they thought they knew and form new alliances... JUSTICE LEAGUE: NO JUSTICE Scott Snyder Joshua Williamson | Francis Manapul On Sale: 9/25/2018 ISBN: 9781401283346 $16.99/$22.99 CAN Trade Paperback JUSTICE LEAGUE: NO JUSTICE Scott Snyder Joshua Williamson | Francis Manapul On Sale: 9/25/2018 ISBN: 9781401283346 $16.99/$22.99 CAN ABOUT THE BOOK Trade Paperback Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, Aquaman and the Flash are finally reunited. When the cosmos suddenly opens up to terrifying new threats, the Justice League must look to their own mythologies to solve a mystery that dates back to the beginning of time. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Scott Snyder is a #1 New York Times best-selling writer and one of the most critically acclaimed scribes in all of comics. His works include Dark Nights: Metal, All Star Batman, Batman, Batman: Eternal, Superman Unchainced, American Vampire and Swamp Thing. -

![1. Over 50 Years of American Comic Books [Hardcover]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4211/1-over-50-years-of-american-comic-books-hardcover-1904211.webp)

1. Over 50 Years of American Comic Books [Hardcover]

1. Over 50 Years of American Comic Books [Hardcover] Product details Publisher: Bdd Promotional Book Co Language: English ISBN-13: 978-0792454502 Publication Date: November 1, 1991 A half-century of comic book excitement, color, and fun. The full story of America's liveliest, art form, featuring hundreds of fabulous full-color illustrations. Rare covers, complete pages, panel enlargement The earliest comic books The great superheroes: Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, and many others "Funny animal" comics Romance, western, jungle and teen comics Those infamous horror and crime comics of the 1950s The great superhero revival of the 1960s New directions, new sophistication in the 1970s, '80s and '90s Inside stories of key Artist, writers, and publishers Chronicles the legendary super heroes, monsters, and caricatures that have told the story of America over the years and the ups and downs of the industry that gave birth to them. This book provides a good general history that is easy to read with lots of colorful pictures. Now, since it was published in 1990, it is a bit dated, but it is still a great overview and history of comic books. Very good condition, dustjacket has a damage on the upper right side. Top and side of the book are discolored. Content completely new 2. Alias the Cat! Product details Publisher: Pantheon Books, New York Language: English ISBN-13: 978-0-375-42431-1 Publication Dates: 2007 Followers of premier underground comics creator Deitch's long career know how hopeless it's been for him to expunge Waldo, the evil blue cat that only he and other deranged characters can see, from his cartooning and his life. -

August 23, 2020

Reporting on the Planet Daily FREE Volume 7 | Issue 3 dailyplanetdc.com August 23, 2020 WARNERMEDIAENTERTAINMENT GIANT SET TO INVESTIGATE JUSTICE LEAGUE RESHOOTS’ TOXIC WORK CLIMATE By Zack Benz Daily Planet Justice League actor, Ray cally untrue that we enabled Fisher, revealed in a tweet a n y u n p r o f e s s i o n a l Thursday that WarnerMedia behavior.” will be launching a third- “I remember [Fisher] be- party investigation after al- ing upset that we wanted legations regarding the tox- him to say ‘Booyaa,’ which is ic and abusive work envi- a well known saying of Cy- ronment created by Geoff borg in the [Teen Titans] an- Johns, Joss Whedon, Jon imated series,” said Berg. Berg and others surfaced The animated series Berg last month. was referring to was the Whedon, the director of popular Cartoon Network Marvel Studios’ blockbuster children’s show, “Teen Ti- superhero movies “ The tans” from the early 2000s Avengers” and “Avengers: where Cyborg’s main catch- Age of Ultron,” took over di- phrase was “Booyaa.” recting duties for Zack Sny- Fisher played the super- der on DC Comics Justice hero Cyborg alongside Gal League. Gadot’s Wonder Woman, Fisher also stated that Ben Affleck’s Batman, Henry former Warner Bros. co- Cavill’s Superman, Jason president of production Jon Momoa’s Aquaman, and Berg, and former DC Enter- Ezra Miller’s the Flash. tainment president and Fisher commented on chief creative officer Geoff Wheadon’s on set treatment Johns both “enabled” Whe- of cast and crew members don. -

D2wxy (Free Read Ebook) Nexus Omnibus Volume 6 Online

D2WXy (Free read ebook) Nexus Omnibus Volume 6 Online [D2WXy.ebook] Nexus Omnibus Volume 6 Pdf Free Mike Baron audiobook | *ebooks | Download PDF | ePub | DOC Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #739639 in Books 2014-09-30 2014-09-30Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 9.03 x .79 x 6.03l, 1.63 #File Name: 1616554738424 pages | File size: 61.Mb Mike Baron : Nexus Omnibus Volume 6 before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Nexus Omnibus Volume 6: 0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Five StarsBy Vicki NothThis was a gift and he absolutely loved it.0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Five StarsBy CustomerGreat series0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. I think Nexus was the best book of the 80'sBy 99andrewI think Nexus was the best book of the 80's, period. However, this volume is a little on the weak side. First, lots of guest artists and not the Dude, never a good thing. Second, the swing of Stan from regular guy to complete psycho (spoilers I guess for a book 25 years old) while somewhat set up was a bit to abrupt. The book was still good - just not up to the heights of other volumes. When a near-death experience pushes the current Nexus into his work with a brutal vengeance, it's up to classic Nexus Horatio Hellpop to step in before he goes too far! But as the Nexuses square off against each other, the mysterious Bad Brains and the nefarious Ursala X. -

Female Friendships in Superhero Comics, 1940S to 1960S and Today Hannah R

Eastern Kentucky University Encompass EKU Libraries Research Award for Undergraduates 2017 Undergraduate Research Award submissions Suffering Sappho! Female Friendships in Superhero Comics, 1940s to 1960s and Today Hannah R. Costelle Eastern Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://encompass.eku.edu/ugra Recommended Citation Costelle, Hannah R., "Suffering Sappho! Female Friendships in Superhero Comics, 1940s to 1960s and Today" (2017). EKU Libraries Research Award for Undergraduates. 2. http://encompass.eku.edu/ugra/2017/2017/2 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in EKU Libraries Research Award for Undergraduates by an authorized administrator of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Eastern Kentucky University Suffering Sappho! Female Friendships in Superhero Comics, 1940s to 1960s and Today Honors Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of HON 420 Fall 2016 By Hannah Costelle Mentor Dr. Jill Parrott Department of English and Theatre i Abstract Suffering Sappho! Female Friendships in Superhero Comics, 1940s to 1960s and Today Hannah Costelle Dr. Jill Parrott, Department of English and Theatre Comic book superheroines are the goddesses of modern times; they are the ideal beautiful, powerful women of America’s collective imagination whom girls have looked up to and emulated for decades. But these iconic examples of womanhood usually lack one of the key elements of humanity that enrich real women’s lives, an element that has been proven to increase women’s autonomy and confidence: female friendships. Wonder Woman may have led armies of female friends in the 1940s when superheroines first appeared in the comics pages, but by the 1950s and ‘60s, female characters confiding in one another and working together in the comics was a rarity. -

Contemporary American Comic Book Collection, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/ft567nb3sc No online items Guide to the Contemporary American Comic Book Collection, ca. 1962 - ca. 1994PN6726 .C66 1962 Processed by Peter Whidden Department of Special Collections and University Archives 2002 ; revised 2020 Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford 94305-6064 [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc PN6726 .C66 19621413 1 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Title: Contemporary American Comic Book Collection Identifier/Call Number: PN6726 .C66 1962 Identifier/Call Number: 1413 Physical Description: 41 box(es)41 comic book boxes ; 28 x 38 cm.(ca. 6000 items) Date (inclusive): circa 1962 - circa 1994 Abstract: The collection consists of a selection of nearly 6000 issues from approximately 750 titles arranged into three basic components by publisher: DC Comics (268 titles); Marvel Comics (224 titles); and other publishers (280 titles from 72 publishers). Publication dates are principally from the early 1960's to the mid-1990's. Collection Scope and Content Summary The collection consists of a selection of nearly 6000 issues from approximately 750 titles arranged into three basic elements: DC Comics, Marvel Comics, and various other publishers. Publication dates are principally from the mid-1960's to the early 1990's. The first part covers DC titles (268 titles), the second part covers Marvel titles (224 titles), and the third part covers miscellaneous titles (280 titles, under 72 publishers). Parts one and two (DC and Marvel boxes) of the list are marked with box numbers. The contents of boxes listed in these parts matches the sequence of titles on the lists. -

Kirby Interview Steve Rude & Mike Mignola Stan Lee's Words Fantastic Four #49 Pencils Darkseid, Red Skull, Doctor Doom, At

THE $5.95 In The US ISSUE #22, DEC. 1998 A 68- PAGE COLLECTOR ISSUE ON KIRBY’S VILLAINS! AN UNPUBLISHED Kirby Interview INTERVIEWS WITH Steve Rude & Mike Mignola COMPARING KIRBY’S MARGIN NOTES TO Stan Lee’s Words STUNNING UNINKED Fantastic Four #49 Pencils SPECIAL FEATURES: Darkseid, Red Skull, Doctor Doom, Atlas Monsters, . s Yellow Claw, n e v e t S e & Others v a D & y b r THE GENESIS OF i K k c a J King Kobra © k r o w t r A . c Unpublished Art n I , t INCLUDING PENCIL n e PAGES BEFORE m n i a THEY WERE INKED, t r e t AND MUCH MORE!! n E l e v r a M NOMINATED FOR TWO 1998 M T EISNER r e AWARDS f r INCLUDING “BEST u S COMICS-RELATED r PUBLICATION” e v l i S 1998 HARVEY AWARDS NOMINEE , m “BEST BIOGRAPHICAL, HISTORICAL o OR JOURNALISTIC PRESENTATION” o D . r D THE ONLY ’ZINE AUTHORIZED BY THE Issue #22 Contents: THE KIRBY ESTATE Morals and Means ..............................4 (the hows and whys of Jack’s villains) Fascism In The Fourth World .............5 (Hitler meets Darkseid) So Glad To Be Sooo Baaadd! ..............9 (the top ten S&K Golden Age villains) ISSUE #22, DEC. 1998 COLLECTOR At The Mercy Of The Yellow Claw! ....14 (the brief but brilliant 1950s series) Jack Kirby Interview .........................17 (a previously unpublished chat) What Truth Lay Beneath The Mask? ..22 (an analysis of Victor Von Doom) Madame Medusa ..............................24 (the larcenous lady of the living locks!) Mike Mignola Interview ...................25 (Hellboy’s father speaks) Saguur ..............................................30 (the -

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections Richard B. Winters Collection Winters, Richard B., Books, 1937-2013

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections Richard B. Winters Collection Winters, Richard B., Books, 1937-2013. 214 feet. Collector. Collection of American and Japanese comic books including Marvel, DC, Dark Horse, and other publishers. Also includes collectible statues, posters, and lithographs. Sample Entry: Comic Title Beginning number and date – ending number and date of series held in Winters Collection Issues Held in Winters Collection Box 1: The A-Team No.1 (March 1984) – No. 3 (May 1984) No. 1-3 Ace Comics Presents Vol. 1, No.1 (May 1987) No. 1, 2, 4 Action Comics No. 1 (June 1938) No. 470, 534-540, 543-544, 546-661 Action Comics Annual No. 1 (October 1987) No. 1-2 Adolescent Radioactive Black Belt Hamsters Massacre Japanese Invasion No. 1 (August 1989) No. 1 Advanced Dungeons and Dragons No. 1 (December 1988) No. 1 Advanced Dungeons and Dragons Annual No. 1 (1990) No. 1 Adventure Comics No. 32 (November 1938) - No. 503 (August 1983) No. 467 The Adventures of Baron Munchausen No. 1 (July 1989) - No. 4 (October 1989) No. 1 The Adventures of Captain Jack No. 1 (June 1986) - No. 12 (1988) No. 4-12 (2 copies of No. 5) The Adventures of Ford Fairlane No. 1 (May 1990) – No. 4 (August 1990) No. 1-4 Adventures of Superman No. 424 (January 1987) No. 424 -474 Adventures of Superman Annual No. 1 (September 1987) No. 1-2 (2 copies of No. 1) Adventures of the Outsiders No. 33 (May 1986) - No. 46 (June 1987) No. 33-46 Agent Unknown No. 1 (October 1987) No. -

An Evolutionary Study of Soundtracks from DC Comics' Superheroes

CRESCENDOS OF THE CAPED CRUSADERS: AN EVOLUTIONARY STUDY OF SOUNDTRACKS FROM DC COMICS’ SUPERHEROES Anna J. DeGalan A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS December 2020 Committee: Jeffrey Brown, Advisor Esther Clinton Jeremy Wallach © 2020 Anna DeGalan All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeffrey Brown, Advisor With the transition from comics to television shows, and later onto the big screen, superheroes gained their own theme songs and soundtracks that captured the attention of the audience for years to come. From catchy musical themes, from the old television shows, to the masterfully scored music blasting from the speakers of movie theaters all over the world, it was superheroes’ uniquely composed soundtracks (in conjunction with SFX, acting cues, and genre conventions of superhero films) that further crafted the iconography that made each character into the superhero being portrayed on-screen. While much of the focus of past textual analysis of films within the superhero genre has focused on characterizations of heroes, visual iconography, and the logistics of filming or framing a scene, academia has vastly overlooked the necessity of a film’s soundtrack, not only as a basic narrative tool and genre locator, but as a means to further understand how a cultural perception of the material is being reflected by the very musical choices presented on a score. While there has been an influx of research focusing on how a culture perceives its heroes – in this case superheroes – during times of great change within a society (either politically, socially, economically, or culturally; for example, the terrorist attack on American soil on 9/11/2001), I have found there to be a lack of research involving how the musical themes of superheroes reflect our cultural views and feelings at a specific point in time. -

CRISIS CHARACTER CARDS Original Text

CRISIS CHARACTER CARDS Original Text ©2011 WIZKIDS/NECA, LLC TM & © DC Comics. (s11) PRINTING INSTRUCTIONS 1. From Adobe® Reader® or Adobe® Acrobat® open the print dialog box (File>Print or Ctrl/Cmd+P). 2. Click on Properties and set your Page Orientation to Landscape (11 x 8.5). 3. Under Print Range>Pages input the pages you would like to print. (See Table of Contents) 4. Under Page Handling>Page Scaling select Multiple pages per sheet. ©2011 WIZKIDS/NECA, LLC TM & © DC Comics. (s11) 5. Under Page Handling>Pages per sheet select Custom and enter 2 by 2. 6. If you want a crisp black border around each card as a cutting guide, click the checkbox next to Print page border. 7. Click OK. ©2011 WIZKIDS/NECA, LLC TM & © DC Comics. (s11) TABLE OF CONTENTS Accomplished Perfect Captain Marvel, Jr., 56 Physician, 50 Chief, 42 Ace, 22 Darkseid, 54 Anti-Monitor, 79 Dawnstar, 28 Anti-Monitor, Guardian Deathstroke, 34 of Fear, 80–81 Donna Troy, 72 Aqualad, 10 Dr. Sivana, 26 Batgirl, 20 The Flash, 63 Batman, 76 Forerunner, 46 Batwoman, 25 Garth, 73 Black Adam, 59 Gold, 15 Blue Beetle, 36 Green Arrow, 32 Boy Wonder, 68 ©2011 WIZKIDS/NECA, LLC TM & © DC Comics. (s11) Green Lantern, 29 Mercury, 14 Harbinger, 45 Monarch, 49 Hawk and Dove, 38 Monitor, 66 Iron, 21 Mordru, 48 Jack and Ten, 31 Nightwing, 35 Jericho, 13 Nightwing and Starfire, 64 Karate Kid, 30 Psimon, 39 Kid Flash, 8 Psycho-Pirate, 58 King and Queen, 57 Red Arrow, 24 Klarion, 17 Red Hood, 23 Kyle Rayner, 43 Rip Hunter, 27 Lead and Tin, 40 Robin (Dick Grayson), 7 Liberty Belle, 16 Robin (Tim Drake), 19 Mammoth, 37 Roy Harper, 74 Mary Marvel, 47 Shadow Demon, 78 ©2011 WIZKIDS/NECA, LLC TM & © DC Comics. -

The League Returns

Volume 11 #6 “News, reviews and opinions from the world of comics” December 2007 The League Returns League Of Extraordinary Gentlemen: Black Dossier HC I think we can all agree that the League of Extraordinary Gentlemen movie wasn’t too good, but there’s a history of mediocre adap- tations of Alan Moore projects. But the truth is, the actual comics have all been excellent. If you’ve let that stop you from trying one of the best books of the last decade, it’s your loss. Seriously, go buy volumes 1 & 2, read them, love them, and then get ready for... The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: Black Dossier! Many years in the making, and many months in production, the thick hard cover tome is fi nally out. Set in a dark England in the 1950s in which the League have been disbanded, it’s up to Mina Murray and Allan Quatermain to fi nd the legendary Black Dossier (the history of the League throughout the ages), before their enemies do. While not technically the third part of the League series, the Black Dossier is a full-length graphic novel, plus lots of cool DVD-style extras! Alan Moore and Kevin O’Neill have outdone themselves on this one. Hopefully DC will keep it in *Editor’s note: Opps, looks print through the holiday season, but I’d like this book is sold out grab a copy now, just to be safe.* at Diamond. Better buy it now before or you’ll be left waiting!!! — Smilin’ Scott Heroes Hits Hardcover Not satisfi ed with only one thirty dollar hardcover this month, DC has also released the Heroes HC, a collection of the super-popular Heroes webcomics.