In It to Win: Jack & Overconfidence Bias

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Low Voter Turnout Among Eligible Seniors Directors of Diversity

VOLUME LXXV ST. LOUIS UNIVERSITY HIGH SCHOOL, FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 5, 2010 sluh.org/prepnews ISSUE 10 Low voter turnout Remembering George Hickenlooper, among eligible seniors the fourth Wednesday of October ’82—award-winning director 44 % of seniors of before the election. PHOTO COURTESY OF SUZANNE HICKENLOOPER Civic duty apparently mo- Today’s masthead is reprinted age vote on tivated the contingent of SLUH from the Dec. 12, 1980 Prep students who did vote. News. It was drawn by George variety of issues Hickenlooper, ’82, the week “I feel like it’s my responsibil- that John Lennon was assas- ity to vote, as an American citizen,” sinated. More of Hickenlooper’s BY CONOR GEARIN said senior David Boll. NEWS EDITOR illustrations can be found inside “It was my first chance to on pg. 3 and online at sluh.org/ olitical rhetoric threatened voice my opinion for my country, prepnews/hickenlooper. to boil over in the weeks so I figured I might as well take leadingP up to the elections this it,” said senior John Taaffe. George Hickenlooper Jr., began Tuesday, with TV attack ads air- Senior David Farel said that taking him regularly to a small ing relentlessly, forests of yard he had not previously been inter- theater in their then-hometown, signs sprouting everywhere, and ested in voting, but felt that voting Los Angeles. It was at this laid round-the-clock coverage of the ultimately is a moral issue. back venue that Hickenlooper races overtaking cable news sta- However, some seniors, was first introduced to the films tions. though registered to vote, abstained of Orsen Wells, Citizen Kane and However, as a whole, St. -

Tribal Lobbying Matters Hearing

S. HRG. 108–720 TRIBAL LOBBYING MATTERS HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON INDIAN AFFAIRS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED EIGHTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION ON OVERSIGHT HEARING REGARDING TRIBAL LOBBYING MATTERS, ET AL SEPTEMBER 29, 2004 NOVEMBER 17, 2004 WASHINGTON, DC ( TRIBAL LOBBYING MATTERS S. HRG. 108–720 TRIBAL LOBBYING MATTERS HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON INDIAN AFFAIRS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED EIGHTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION ON OVERSIGHT HEARING REGARDING TRIBAL LOBBYING MATTERS, ET AL SEPTEMBER 29, 2004 WASHINGTON, DC ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 96–229 PDF WASHINGTON : 2005 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON INDIAN AFFAIRS BEN NIGHTHORSE CAMPBELL, Colorado, Chairman DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii, Vice Chairman JOHN McCAIN, Arizona, KENT CONRAD, North Dakota PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico HARRY REID, Nevada CRAIG THOMAS, Wyoming DANIEL K. AKAKA, Hawaii ORRIN G. HATCH, Utah BYRON L. DORGAN, North Dakota JAMES M. INHOFE, Oklahoma TIM JOHNSON, South Dakota GORDON SMITH, Oregon MARIA CANTWELL, Washington LISA MURKOWSKI, Alaska PAUL MOOREHEAD, Majority Staff Director/Chief Counsel PATRICIA M. ZELL, Minority Staff Director/Chief Counsel (II) C O N T E N T S Page Statements: Abramoff, Jack, Washington, DC .................................................................... 14 Campbell, Hon. Ben Nighthorse, U.S. Senator from Colorado, chairman, Committee on Indian Affairs ....................................................................... 1 Conrad, Hon. Kent, U.S. Senator from North Dakota .................................. 9 Dorgan, Hon. Byron L., U.S. Senator from North Dakota ............................ 11 Inouye, Hon. -

Abramoff: Lobbying Congress

Abramoff: Lobbying Congress On March 29, 2006, former lobbyist Jack Abramoff was sentenced to six years in federal prison after pleading guilty to mail fraud, tax evasion, and conspiracy to bribe public officials. Key to Abramoff’s conviction were his lobbying efforts that began in the 1990s on behalf of Native American tribes seeking to establish gambling on reservations. In 1996, Abramoff began working for the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians. With the help of Republican tax reform advocate Grover NorQuist, and his political advocacy group Americans for Tax Reform, Abramoff defeated a Congressional bill that would have taxed Native American casinos. Texas Representative and House Majority Whip Tom DeLay also played a major role in the bill’s defeat. DeLay pushed the agenda of Abramoff’s lobbying clients in exchange for favors from Abramoff. In 1999, Abramoff similarly lobbied to defeat a bill in the Alabama State Legislature that would have allowed casino-style games on dog racing tracks. This bill would have created competition for his clients’ casino businesses. Republican political activist Ralph Reed, and his political consulting firm Century Strategies, aided the effort by leading a grassroots campaign that rallied Alabama-based Christian organizations to oppose the bill. As Abramoff’s successes grew, his clients, political contacts, and influence expanded. He hired aides and former staff of members of Congress. In 2001, Abramoff began working with Congressman DeLay’s former communications director, Michael Scanlon, who had formed his own public affairs consulting firm, Capitol Campaign Strategies. The Coushatta Tribe of Louisiana hired Abramoff and Capitol Campaign Strategies to help them renegotiate their gambling agreement with the State of Louisiana. -

Advocates for Social Justice Film Project Presents

Unitarian Universalist Congregation, Santa Rosa Advocates for Social Justice Film Project Presents: th The 8 in our CORRUPTION OF OUR DEMOCRACY SERIES “Jack Abramoff could sweet-talk a dog off a meat truck”, words voiced by Neil Volz, a disgraced former associate of the notorious Washington super-lobbyist Jack Abramoff. This 2010 documentary tells the story of the high life and eventual downfall of wealthy Republican lobbyist, businessman and con man Jack Abramoff. Abramoff was involved in a massive corruption scandal that led to the conviction of himself, two Bush White House officials, Representative Bob Ney and nine other lobbyists and congressional staffers. Abramoff was convicted of fraud, conspiracy, and tax evasion in 2006 and of trading expensive gifts, meals and sports trips in exchange for political favors. We meet a number of familiar Republican folks as this story unfolds, from Grover Norquist and Ralph Reed to Karl Rove and President George W. Bush. From the director, Alex Gibney, in an interview with Amy Goodman: "You know, he's now called 'disgraced lobbyist Jack Abramoff,' and a lot of people like to say that they didn't really know him. In fact, he was in the mainstream. He was very much a power broker in Washington, DC, (with) very good relationships with Karl Rove, President Bush, and particularly Tom DeLay, the former Majority Whip. So that's the big story about Jack Abramoff. He was a guy who really bought and sold politicians, is really what he did." Discussion follows viewing of the film Please bring whatever you wish to eat. -

IPG Spring 2020 Film Titles - January 2020 Page 1

Film Titles Spring 2020 {IPG} Stars and Wars (2nd Edition) The Film Memoirs and Photographs of Alan Tomkins Alan Tomkins, Oliver Stone A paperback edition of Oscar-nominated Alan Tomkins' film memoirs and photographs Summary The History Press In Stars and Wars , Oscar-nominated art director Alan Tomkins reveals his unpublished film artwork and 9780750992565 behind-the-scenes photographs from an acclaimed career that spanned over 40 years in both British and Pub Date: 5/1/20 Hollywood cinema. Tomkins’ art appeared in celebrated films such as Saving Private Ryan , JFK , Robin Hood On Sale Date: 5/1/20 $34.95 USD/£20.00 GBP Prince of Thieves , The Empire Strikes Back (which would earn him his Oscar nomination), Lawrence of Arabia , Discount Code: LON Casino Royale , Battle of Britain and Batman Begins , and he shares his own unique experiences alongside Trade Paperback these wonderful illustrations and photographs for the very first time. Having worked alongside eminent 168 Pages directors such as David Lean, Oliver Stone, Stanley Kubrick, Franco Zeffirelli and Clint Eastwood, Tomkins has Carton Qty: 1 now produced a book that is a must-have for all lovers of classic cinema. Performing Arts / Film & Video Contributor Bio PER004010 Alan Tomkins ' film career spanned more than 40 years, in which time he went from being a draughtsman on 8.9 in H | 9.8 in W Lawrence of Arabia to becoming an acclaimed and sought-after art director on films such as Saving Private Ryan , The Empire Strikes Back , JFK, Casino Royale , and Batman Begins . Oliver Stone worked with Tomkins on Natural Born Killers and JFK . -

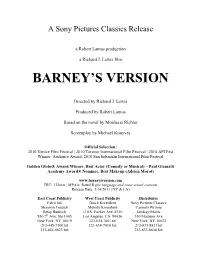

Barney's Version

A Sony Pictures Classics Release a Robert Lantos production a Richard J. Lewis film BARNEY’S VERSION Directed by Richard J. Lewis Produced by Robert Lantos Based on the novel by Mordecai Richler Screenplay by Michael Konyves Official Selection: 2010 Venice Film Festival | 2010 Toronto International Film Festival | 2010 AFI Fest Winner: Audience Award, 2010 San Sebastián International Film Festival Golden Globe® Award Winner, Best Actor (Comedy or Musical) – Paul Giamatti Academy Award® Nominee, Best Makeup (Adrien Morot) www.barneysversion.com TRT: 132min | MPAA: Rated R (for language and some sexual content) Release Date: 1/14/2011 (NY & LA) East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor Falco Ink Block Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Shannon Treusch Melody Korenbrot Carmelo Pirrone Betsy Rudnick 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 Lindsay Macik 850 7th Ave, Ste 1005 Los Angeles, CA 90036 550 Madison Ave New York, NY 10019 323-634-7001 tel New York, NY 10022 212-445-7100 tel 323-634-7030 fax 212-833-8833 tel 212-445-0623 fax 212-833-8844 fax BARNEY’S VERSION Cast: Paul Giamatti Dustin Hoffman Rosamund Pike Minnie Driver Rachelle Lefevre Scott Speedman Bruce Greenwood Macha Grenon Jake Hoffman Anna Hopkins Thomas Trabacchi Cle Bennett Harvey Atkin Massimo Wertmuller Howard Jerome Linda Sorensen Paul Gross David Cronenberg Denys Arcand Atom Egoyan Ted Kotcheff 2 Short Synopsis Based on Mordecai Richler's award winning novel – his last and, arguably, best – BARNEY'S VERSION is the warm, wise and witty story of the politically incorrect life of Barney Panofsky (Paul Giamatti), who meets the love of his life (Rosamund Pike) at his wedding - and she is not the bride. -

Gingrich and His Philanthropy

THE NCRP QUARTERLY | WINTER 2006 Gingrich and His Philanthropy: The Wrong Signal for the Sector and Accountability Gingrich invited as keynoter at Council on Foundation’s Annual Conference By Rick Cohen To its credit, the Council on powerful session, and the Foundations is making an transcript available at the effort to include conserva- center’s Web site1 is well tive viewpoints at its worth the read to understand upcoming annual confer- conservative perspectives on ence in May. There is much the nonprofit sector. to be learned from the lead- So why—with so many ers of the conservative powerful and thoughtful movement, whose politics conservative thinkers to have dominated our society choose from—would the off and on for the past two Council on Foundations opt decades or more. to recruit former Speaker of One of the more stirring the House of Representatives discussions of philanthropy and rumored presidential occurred not all that long candidate Newt Gingrich as ago at the Hudson Institute’s an upcoming keynote speak- Bradley Center for er? There’s nothing wrong Philanthropy and Civic Renewal, during a program titled with hearing Gingrich’s take on public events, but as a “Vision and Philanthropy.” The Weekly Standard’s Bill keynoter on philanthropy? Kristol, the Heritage Foundation’s Stuart Butler, the Gingrich’s track record of philanthropic benevolence in Manhattan Institute’s Heather MacDonald, David Keene of the 1990s earned him several years of serious scrutiny the American Conservative Union, and several others pro- from the Internal Revenue Service and a troubling ethics vided remarkably erudite perspectives, hardly in lock-step review by the House Committee on Standards of Official agreement, on the past and future of American philanthro- Conduct (back in the days when the ethics committee py. -

Jack & Rationalizations

In It To Win: Jack & Rationalizations In It To Win: Jack & Rationalizations introduces the concept of rationalizations, which are the excuses people give themselves for not living up to their own, or society’s, own ethical standards. For example, an employee might pad their expense account while telling themselves that “everybody does it.” Rationalizations play an incredibly important role in facilitating unethical behavior. Questions for classroom discussions In It To Win: Jack & Rationalizations 1) Can you explain in your own words how rationalizations work to facilitate unethical activity? 2) Can you give examples of common rationalizations that are used in the business world? 3) Can you give examples of rationalizations that Jack Abramoff used? 4) Can you think of situations where you have used rationalizations? 5) How can we guard against rationalizing our own wrongdoing? 6) Dan Ariely and colleagues ran an experiment where a clerk gave too much change to the subject of the experiment. In general 45% of the subjects returned the extra change. However, when Ariely had the clerk annoy the subject by rudely ignoring them for just a bit, only 14% returned the extra change. How might the rationalization process have played a role in the outcome of these experiments? 7) Murphy and Mayhew ran a study in which they learned that when people misreport numbers they generally feel bad, but they don’t feel as bad if they were instructed to do so by superiors. How might the rationalization process play a role in this outcome? 1 Additional Teaching Note The instructional resources in this series include a feature documentary, In It To Win: The Jack Abramoff Story (25 minutes), and six short videos (approx. -

Investigation of Tribal Lobbying Matters, September

CHAPTER III CAPITAL ATHLETIC FOUNDATION ABRAMOFF: The package on the ground is $4K per person. that [sic] covers rooms, tee times and ground transpor- tation. One idea is that we could use one of my founda- tions for the trip—Capital Athletic Foundation—and get and make contributions so this is easier. OK? REED: OK but we need to discuss. It is an election year. Email between Jack Abramoff and Ralph Reed concerning golfing junket to Scot- land, May 15, 2002 RUDY: J ack wants this. BOULANGER: What is it? I’ve never heard of it. RUDY: It is something our friends are raising money for. BOULANGER: I’m sensing shadiness. I’ll stop asking. Email between Todd Boulanger and Tony Rudy concerning suggested Tribal con- tributions to CAF, June 20, 2002 BOZNIAK: He [CAF funds recipient Shmuel Ben Svi] did suggest that he could write some kind of letter with his Sniper Workshop Logo and letter head. It is an ‘‘edu- cational’’ entity of sorts. ABRAMOFF: no [sic] I don’t want a sniper letterhead. Email between Jack Abramoff and Allison Bozniak, September 19, 2002 A. INTRODUCTION At its hearings over the past two years, the Committee disclosed and discussed evidence that Jack Abramoff might have used Cap- ital Athletic Foundation (‘‘CAF’’), his private charitable foundation, in ways grossly inconsistent with its tax exempt status and mis- sion. Based on multiple interviews and records, the Committee con- clusively finds that (1) CAF was simply another vehicle in Abramoff and Scanlon’s ‘‘gimme five’’ scheme; (2) Indian tribes paid CAF, directly and indirectly, knowingly and unknowingly, approxi- mately $3,657,000; and, (3) Abramoff treated CAF as his own per- sonal slush fund, apparently using it to evade taxes, finance lob- bying activities such as a golfing trip to Scotland, purchase para- military equipment, and for other purposes inconsistent with CAF’s tax exempt status and stated mission. -

Casino Jack Just a Few Months Ago, a Major Documentary Film Was

Casino Jack Just a few months ago, a major documentary film was released called “Casino Jack and the United States of Money” which outlined the stunning rise and abrupt fall of the Washington über-lobbyist Jack Abramoff (see my take in the “Reviews” section on this site). That film, made by documentarist Alex Gibney, gave a vigorous, warts and all, portrayal of this super-hustler of the Bush Era as he suborned officials and legislators, feathered his luxury nest, and offered a calamitous model of hard-ball politics. Turns out that the Abramoff story was entertaining enough to trigger another telling, this time in a fiction film called “Casino Jack” (no originality there) and starring Kevin Spacey as smiling Jack. Here, however, the tenor of the film is sardonic wit and knowing snideness, confirming to audience members just how unbelievably crass our political process has become. Call it a comedy of bad manners. Spacey, as a matter of fact, looks nothing like the real Abramoff, but it hardly matters (especially to viewers outside Washington, who have little sense of the man as a public figure) because, while the real Jack was coarse and fat, the actor is cool and slim. However, Spacey is also appropriately oily and smooth, the very picture of a well- dressed slimeball who could say just the right things to a beleaguered Congressman or a cowed bureaucrat. The one time the film tries to duplicate the actual Abramoff is the image everybody remembers, when the man is under indictment, with his (semi-famous) black flat-brim fedora and pinched double-breasted coat. -

DU Alumnus Tom Rodgers Sought Justice for Fellow Native Americans in One of the Largest Scandals Washington Had Ever Seen

DU Alumnus Tom Rodgers Sought Justice For Fellow Native Americans In One Of The Largest Scandals Washington Had Ever Seen Lisa Marshall Special Report Editor’s Note: In January, 2006, Washington D.C. lobbyist Jack Abramoff pleaded guilty to fraud, tax evasion, and conspiracy to bribe public officials, and admitted to defrauding American Indian tribes out of tens of millions of dollars. His plea (and the more than two years of testimony he has since provided about his powerful Capitol Hill allies) exposed the largest congressional influence peddling scandal in history, led to a dozen indict- ments, landed one congressman in jail, and precip- itated a sweeping ethics reform bill. A new light on the practice of lobbyists buying favors from politi- cians, and some say D.C. will never be the same. But little is known about just how Abramoff was exposed, and by whom. In fact, it was a small group of Native Americans – including DU Law graduate Tom Rodgers (JD'86, LLM'88) – who worked behind the scenes for years to help bring Abramoff and his circle of co-conspirators to jus- tice. This is their story. Tom Rodgers had just flipped on only his closest friends and family to their lands, or forestalling rebel leader, Jonas Savimbi. an early-morning ESPN recap of a members what he was up to. In a perceived legislative threats, “I started stringing the pearls Pittsburgh Steelers game when – at sense, some associates say, he was Abramoff’s close alliances with together,” says Rodgers, who began 1 a.m. on a January day in 2003 – the “Deep Throat” of the D.C. -

Casino Jack Recently Had Its World Premiere at the 2010 Toronto International Film Festival 1

In Association with ROLLERCOASTER ENTERTAINMENT, HANNIBAL PICTURES and TRIGGER STREET PRODUCTIONS A ROLLERCOASTER ENTERTAINMENT, MCG and VORTEX WORDS + PICTURES Production In association with AN OLIVE BRANCH Kevin Spacey Barry Pepper Kelly Preston Jon Lovitz with Rachelle Lefevre and Maury Chaykin Directed by George Hickenlooper RATING: R RUNNING TIME: 108 Minutes STUDIO CONTACT: NEW YORK AGENCY: LOS ANGELES AGENCY: IDP/ATO Pictures 42West GS Entertainment Marketing Group Liza Burnett Fefferman Tom Piechura Steven Zeller Teresa DiMartino 220 W 42nd Street 12th Fl. Todd Zeller 1133 Broadway Suite 1120 New York, NY 10036 522 No. Larchmont Blvd. New York, NY 10010 212.277.7552 Los Angeles, CA 90004 212.367.9435 [email protected] 323.860.0270 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] CASINO JACK RECENTLY HAD ITS WORLD PREMIERE AT THE 2010 TORONTO INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL 1 DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT In 2005, when the lobbying scandal surrounding Jack Abramoff and Michael Scanlon broke, and how, together, they were involved in what was being touted as the biggest political impropriety to hit the Beltway since Watergate, I became fascinated. It was a story of hubris and greed so Gothic that as details unfolded it seemed to play out more like a satiric novel by Paddy Chayefsky rather than Woodward's non fiction masterpiece All the President’s Men. More interestingly, Abramoff came to be an icon of the “culture of greed” that seemed to be sweeping the capitol. The butt of jokes from Letterman to Leno, scorned publicly by George Clooney while he accepted his Golden Globe award for GOOD NIGHT AND GOOD LUCK, Abramoff became the focus of news specials and documentaries that made his outrageous misdeeds seem worthy of the big screen.