Country Report Cyprus 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Income and Wealth Inequality in Cyprus: Empirical Evidence from the Household Finance and Consumption Survey§

Cyprus Economic Policy Review, Vol. 14, No. 2, pp 50-60 (2020) 1450-4561 Income and Wealth Inequality in Cyprus: Empirical evidence from the Household Finance and Consumption Survey§ Ioanna Evangelou a , Rozmari Hadjicharalambous a, b and Nektarios A. Michail *, a, c a Economic Analysis and Research, Central Bank of Cyprus b Department of Economics, University of Cyprus c Department of Commerce, Finance, Shipping, Cyprus University of Technology, and Cyprus Centre for Business Research. ________________________________________________________ Abstract We estimate the Gini Coefficient for total income, total wealth, net income and net wealth in Cyprus, using microdata from the Eurosystem Household Finance and Consumption Survey over the years 2009-2017. The results suggest that net income inequality increased slightly from 2009 to 2013, most likely attributed to the economic crisis and its consequences on households. After the end of the crisis and during the recovery period, net income inequality decreased. On the other hand, wealth inequality increased significantly in the recovery period, potentially attributed to the deleveraging behaviour observed by many middle and low-income households, who reduced the liabilities they had accumulated before the economic crisis. Wealthier households appear to have potentially benefited from the increase in real estate prices and the decrease in interest rates during the recovery. Keywords: HFCS, Inequality, Survey, Wealth, Cyprus 1. Introduction Economic inequality in a country is created when income or wealth is not distributed equally between the populations and a gap is created between those considered as the rich, at the top percentile of the distribution, and the poor, at the bottom percentile of the distribution (Kuznets, 1995). -

Report Following His Visit To

CommDH(2016)16 Strasbourg, 31 March 2016 English only REPORT BY NILS MUIŽNIEKS COMMISSIONER FOR HUMAN RIGHTS OF THE COUNCIL OF EUROPE FOLLOWING HIS VISIT TO CYPRUS FROM 7 TO 11 DECEMBER 2015 d Summary.........................................................................................................................................................1 Introduction....................................................................................................................................................4 1 Human Rights of Asylum seekers, Refugees and Immigrants ...................................................................5 1.1 Issues concerning the right to seek and enjoy asylum in Cyprus .............................................................5 1.1.1 An overview of the Cypriot asylum system........................................................................................5 1.1.2 Length of asylum procedures.............................................................................................................6 1.1.3 Access to legal assistance...................................................................................................................7 1.1.4 Access to effective remedies..............................................................................................................7 1.1.5 Situation of unaccompanied asylum seeking children.......................................................................8 1.2 Issues concerning reception of asylum seekers and social integration....................................................9 -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Personal Information Name Christos Surname Koutsampelas Date of birth 13 November 1979 Nationality Greek Phone (office) + 30 2741075638 E-mail [email protected] Education 2004-2009 Ph.D. in Economics, Athens University of Economics and Business, Department of International and European Economic Studies. Dissertation: “The distributional effects of non-cash incomes in Greece”, Supervisor: Panos Tsakloglou. 2002-2003 M.Sc. in International Economics, Athens University of Economics and Business, Department of International and European Economic Studies. 1997-2002 B.A. in Economics, Athens University of Economics and Business, Department of Economics. Professional /Research experience Today- Assistant Professor, Department of Social and Educational Policy, University of Peloponnese. 2011-2018 Researcher, Economics Research Centre, University of Cyprus. 2006-2009 Researcher, Research Programme AIM-AP (Accurate Income Measurement for the Assessment of Public Policy), European Commission. 1 Curriculum Vitae Teaching experience 2018-today Undergraduate level: - Economics of Education (Core elective course) - Quantitative Methodology (Compulsory course) - Statistical Data Analysis (Compulsory course) - Methodology in Social and Educational Research (Compulsory Course) - Research Proposal Writing Techniques (Free elective course) Postgraduate level: - Economics of Education Other professional experience 2017-2018 National Coordinator for Cyprus and National Expert on Social Inclusion, European Social Policy Network 2014-2016 National Expert in Social Inclusion for Cyprus, European Social Policy Network. 2014 Expert, for the impact assessment of the introduction of the Guaranteed Minimum Income scheme in Cyprus), for International Labour Office (ILO) and Ministry of Labour and Social Insurance (MLSI). 2011-2013 Member of the Νetwork of Independent Experts on Social Inclusion. 2011 Research Associate, Labour Institute of the Greek General Confederation of Greece. -

The Identity Conflict of the Cypriots the Cypriot Mule

Uluslararası Sosyal Araştırmalar Dergisi The Journal of International Social Research Cilt: 10 Sayı: 52 Volume: 10 Issue: 52 Ekim 2017 October 2017 www.sosyalarastirmalar.com Issn: 1307-9581 Doi Number: http://dx.doi.org/10.17719/jisr.2017.1898 THE IDENTITY CONFLICT OF THE CYPRIOTS • THE CYPRIOT MULE CORPS IN THE FIRST WORLD WAR Nur ÇETİNER** Abstract Cypriot muleteers served in the British army in the Macedonian front during the First World War. Both Cypriot men and island mules were used in the war. Mules were used in the war due to their carrying ability under harsh geographical conditions. The British government utilized the existing economic problems in Cyprus to attract Cypriot support. For some Cypriots joining the war serving in the army was the only way to provide for the livelihood of their family. In fact, Turkish Cypriots participated in the Great War against the Ottoman Empire. Furthermore, there were differences in terms of religious creed between Greek Cypriots and the British: the Greek Cypriots were Orthodox while the British people were Protestant. Hence, both Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots had some troubles about joining the Great War. Despite these differences, Greek and Turkish Cypriots set aside their national and religious feelings and were united in the same army to serve Great Britain. Another important aspect of the Cypriot Mule Corps lies in the fact that the Turkish Cypriots joined the British army not only against their former Sultan but also against their compatriots who migrated to Anatolia and were subsequently recruited to the Ottoman army. Overall, this article aims to illustrate this complex situation of the Cypriot Mule Corps from the standpoint of Cypriots and to show that people can ignore their national and religious identities when they have to. -

Mj0420245enn.En .Pdf (PDF)

EU ENERGY POVERTY Observatory Member State Reports on Energy Poverty 2019 Energy Manuscript completed in May 2020 Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on behalf of the Commission is responsible for the use that might be made of the following information. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2020 PDF ISBN 978-92-76-18582-6 doi: 10.2833/81567 MJ-04-20-245-EN-N © European Union, 2020 Reuse is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. The reuse policy of European Commission documents is regulated by Decision 2011/833/EU (OJ L 330, 14.12.2011, p. 39). For any use or reproduction of photos or other material that is not under the EU copyright, permission must be sought directly from the copyright holders. Contents Introduction 2 Austria 3 Belgium 7 Bulgaria 11 Croatia 15 Cyprus 19 Czechia 23 Denmark 27 Estonia 31 Finland 35 France 39 Germany 43 Greece 47 Hungary 51 Ireland 55 Italy 59 Latvia 63 Lithuania 67 Luxembourg 71 Malta 75 Netherlands 79 Poland 83 Portugal 87 Romania 91 Slovakia 95 Slovenia 99 Spain 103 Sweden 107 United Kingdom 111 1 Introduction The EU Energy Poverty Observatory (EPOV) is an initiative by the European Commission to support Member States in their efforts to alleviate energy poverty. Its principal mission is to engender transformational change in knowledge about the state of energy poverty in Europe, and innovative policies and practices to reduce it. The creation of EPOV is part of the European Commission’s policy efforts to address energy poverty across the EU Member States. -

Report on Disaster Risk Management in the Republic of Cyprus

REPUBLIC OF CYPRUS CYPRUS CIVIL DEFENCE MINISTRY OF INTERIOR GENERAL DIRECTORATE Report on Disaster Risk Management in the Republic of Cyprus Prepared in compliance with Art. 6(1)d of Decision No 1313/2013/EU October 2020 Page 1 of 35 Editor in chief: Dr. Nicholas Paris, Director of Civil Defence, [email protected] Micro-Editors: Maria Ntritsou, Civil Defence Officer A, [email protected] and Olyvia Michaelidou Civil Defence Officer A, [email protected] Organisation: Cyprus Civil Defence, 23 Kennedy Street, Lakatamia, 2314 Nicosia, CYPRUS, Tel. 00357 22403413, Fax. 0035722315638. Site http://www.moi.gov.cy/moi/cd email [email protected] This report is prepared in compliance with Art. 6(1)d of Decision No 1313/2013/EU Note1: References to Decision No 1313/2013/EU (OJ L 347, 20.12.2013, p. 924) should be understood as: Decision No 1313/2013/EU as amended by Decision (EU) 2019/420 (OJ L 77 I, 20.3.2019, p. 1) In light of Article 28(1)a of Decision No 1313/2013/EU. Where reference is made to Member States, it shall be understood as including Participating States as defined in Article 4(12) of Decision No 1313/2013/EU. Note 2: Information contained in this report has been obtain from governmental sources, during 2020, believed to be reliable at the time the information was released. Note 3: Although no sensitive elements are published in this report, no information contained herein may be published or be made otherwise available except on a need-to-see basis by the EU Commission and its associates. -

Cyprus and Its Responsibility Towards the World's Poor

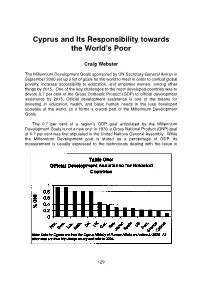

Cyprus and Its Responsibility towards the World’s Poor Craig Webster The Millennium Development Goals sponsored by UN Secretary-General Annan in September 2000 set up a list of goals for the world to meet in order to combat global poverty, increase accessibility to education, and empower women, among other things by 2015. One of the key challenges to the most developed countries was to devote 0.7 per cent of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) to official development assistance by 2015. Official development assistance is one of the means for investing in education, health, and basic human needs in the less developed societies of the world, so it forms a crucial part of the Millennium Development Goals. The 0.7 per cent of a region’s GDP goal articulated by the Millennium Development Goals is not a new one: in 1970, a Gross National Product (GNP) goal of 0.7 per cent was first stipulated in the United Nations General Assembly. While the Millennium Development goal is stated as a percentage of GDP, its measurement is usually expressed to the technocrats dealing with the issue in 129 THE CYPRUS REVIEW (VOL. 19:2 FALL 2007) terms of a percentage of the Gross National Income (GNI) which, taking subsidies into consideration is a measure of the size of the economy of a country. It can be seen in table 1 that as far as the goal of reaching the minimum amounts of official development assistance as GNI, few countries have lived up to the 0.7 per cent goal they agreed to meet. -

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 26.2.2020 SWD(2020) 512 Final

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 26.2.2020 SWD(2020) 512 final COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT Country Report Cyprus 2020 Accompanying the document COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE EUROPEAN COUNCIL, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN CENTRAL BANK AND THE EUROGROUP 2020 European Semester: Assessment of progress on structural reforms, prevention and correction of macroeconomic imbalances, and results of in-depth reviews under Regulation (EU) No 1176/2011 {COM(2020) 150 final} EN EN CONTENTS Executive summary 4 1. Economic situation and outlook 8 2. Progress with country-specific recommendations 16 3. Summary of the main findings from the MIP in-depth review 22 4. Reform priorities 28 4.1. Public finances and taxation 28 4.2. Financial sector 33 4.3. Labour market, education and social policies 42 4.4. Competitiveness, reforms and investment 52 4.5. Environmental sustainability 62 Annex A: Overview Table 67 Annex B: Commission debt sustainability analysis and fiscal risks 75 Annex C: Standard Tables 76 Annex D: Investment guidance on Just Transition Fund 2021-2027 for Cyprus 82 Annex E: Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 84 References 89 LIST OF TABLES Table 1.1: Key economic and financial indicators – Cyprus 15 Table 2.1: Assessment of the 2019 country-specific recommendations implementation 18 Table 3.1: Macroeconomic imbalance procedure assessment matrix – Cyprus 26 Table 4.2.1: Financial soundness indicators, all banks in Cyprus 35 Table 4.4.1: Selected indicators on digitalisation of businesses, -

FES CYPRUS NEWSLETTER Nr. 58 / APRIL 2017

FES CYPRUS NEWSLETTER Nr. 58 / APRIL 2017 Contents 1. Cyprus Problem ....................................................................................... 2 2. Hydrocarbons .......................................................................................... 4 3. Greek Cypriots ........................................................................................ 6 Economic Developments ........................................................................ 6 Domestic Developments ......................................................................... 7 Foreign policy .......................................................................................... 8 Labour Relations and Trade Unions ........................................................ 8 4. Turkish Cypriots ...................................................................................... 9 Economic Developments ........................................................................ 9 Relations with Turkey ........................................................................... 10 Domestic Developments ....................................................................... 10 Labor Relations and Trade Unions ........................................................ 11 Foreign Policy ........................................................................................ 11 5. FES Cyprus Events ................................................................................. 12 FES NEWS - please follow and visit us on - @FESCyprus - www.FEScyprus.org - www.facebook.com/FEScyprus -

ESPN Thematic Report on Social Investment

ESPN Thematic Report on Social Investment Cyprus 2015 Panos Pashardes with Christos Koutsampelas and Mamas Theodorou January – 2015 EUROPEAN COMMISSION Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion Directorate D — Europe 2020: Social Policies Unit D.3 — Social Protection and Activation Systems Contact: Valdis ZAGORSKIS E-mail: [email protected] European Commission B-1049 Brussels EUROPEAN COMMISSION EUROPEAN SOCIAL POLICY NETWORK (ESPN) ESPN Thematic Report on Social Investment Cyprus 2015 Panos Pashardes with Christos Koutsampelas and Mamas Theodorou Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion 2015 The European Social Policy Network (ESPN) was established in July 2014 on the initiative of the European Commission to provide high-quality and timely independent information, advice, analysis and expertise on social policy issues in the European Union and neighbouring countries. The ESPN brings together into a single network the work that used to be carried out by the European Network of Independent Experts on Social Inclusion, the Network for the Analytical Support on the Socio-Economic Impact of Social Protection Reforms (ASISP) and the MISSOC (Mutual Information Systems on Social Protection) secretariat. The ESPN is managed by CEPS/INSTEAD and APPLICA, with the support of OSE - European Social Observatory. For more information on the ESPN, see: http://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=1135&langId=en Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union. Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) The information given is free, as are most calls (though some operators, phone boxes or hotels may charge you). -

THE CYPRUS REVIEW a Journal of Social, Economic and Political Issues

THE CYPRUS REVIEW A Journal of Social, Economic and Political Issues James Ker-Lindsay An Irreparable Breakdown of Trust: Relations between the UN Secretary-General and the Greek Cypriots Before and After the 2004 Referendum Evagoras C. Leventis and Andreas Tsokkalides Protracted Social Conflict Analysis and Cyprus: An Assessment Emel Akçali The ‘Other’ Cypriots and their Cyprus Questions Andreas Stergiou Soviet Policy toward Cyprus Marina Vasilara and Gotelenne Piaton The Role of Civil Society in Cyprus Commentary Articles by Mike Hajimichael Craig Webster Book Reviews Oliver P. Richmond and Henry F. Carey Subcontracting Peace: The Challenges of NGO Peacebuilding Stefan Talmon Collective Non-Recognition of Illegal States Evanthis Hatzivassiliou Greece and the Cold War: Frontline State, 1952-1967 Volume 19 Fall 2007 Number 2 Published by INTERCOLLEGE / UNIVERSITY OF NICOSIA V O L U M E 19 N U M B E R 2 THE CYPRUS REVIEW A Journal of Social, Economic and Political Issues The Cyprus Review, a Journal of Social, Economic and Political Issues, P.O. Box 24005, 1700 Nicosia, Cyprus. Telephone: 22-353702 ext 301, 22-841500 E-mail:[email protected] Telefax: 22-353682, 22-357481, www.unic.ac.cy To access site: > Research > UNic Publications Subscription Office: The Cyprus Review University of Nicosia 46 Makedonitissas Avenue 1700 Nicosia, Cyprus Copyright: © 2007 University of Nicosia, Cyprus. ISSN 1015-2881. All rights reserved. No restrictions on photo-copying. Quotations from The Cyprus Review are welcome, but acknowledgement of the source must be given. TCR Staff Editor in Chief: Hubert Faustmann Co-Editors: James Ker-Lindsay Craig Webster Managing Editor: Nicos Peristianis Assistant Editor: Christina McRoy V O L U M E 19 N U M B E R 2 THE CYPRUS REVIEW A Journal of Social, Economic and Political Issues Peter Allen, Ph.D., Rhode Island College, U.S.A. -

Food, Housing, Family and Welfare Regimes

Food, Housing, Family and Welfare Regimes: The Case of Cyprus Christos Minas, BA, MSc (Accounting and Finance) Submitted for the award of PhD Dublin City University Business School Dublin City University Supervisors: Professor David Jacobson Professor Darach Turley Dr Caroline McMullan January 2013 I hereby certify that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of PhD is entirely my own work, that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge breach any law of copyright, and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed: ____________ (Candidate) ID No.: 54174538 Date: _______ 1 Acknowledgments This dissertation would not have been possible without the guidance and the help of several individuals who in one way or another contributed and extended their valuable assistance in the preparation and completion of this study. First and foremost, my utmost gratitude to Professor David Jacobson whose sincerity and encouragement I will never forget. Professor Jacobson has been my inspiration as I hurdle all obstacles in the completion of this thesis. Dr Caroline McMullan stood by me and supported me in difficult times, showing me light at the end of the tunnel when everything seemed dark to me. Professor Darach Turley deserves thanks for his unselfish and unfailing support as my co- supervisor. When it comes to thanking family for pointing me towards education, there is one person who deserves credit and that is my mother, Veta.