Master's Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 the Intersection Between Politics

1 THE INTERSECTION BETWEEN POLITICS, CULTURE, AND SPIRITUALITY: AN INTERDISCIPLINARY INVESTIGATION OF PERFORMANCE ART ACTIVISM AND CONTEMPORARY SOCIETAL PROBLEMS A Thesis Presented to The Honors Tutorial College Ohio University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation from the Honors Tutorial College with the degree of Bachelor of Fine Arts in Dance by Justin M. Middlebrooks June 2012 2 This thesis has been approved by The Honors Tutorial College and the School of Dance Marina Walchli Professor, Dance Thesis advisor Marina Walchli Professor, Dance Honors Tutorial College Director of Studies, Dance Jeremy Webster Dean, Honors Tutorial College 3 Contents Foreword Initial Interactions with Culture, Politics, and Spirituality 4 One An Introduction to the Project 9 Two Perspectives on Contemporary Movements and Sociopolitical Problems 13 Three Performance Art and Activism 31 Four An Emerging Cultural Paradigm Shift 43 Five Summary and Conclusion 66 Glossary 69 Appendix I 71 Appendix II 124 Appendix III DVD Works Cited 143 4 Foreword Initial Interactions with Culture, Politics, and Spirituality Since my early childhood, and throughout my young adult life, I diligently pursued various cultural experiences and forms of artistic expression. My primary interest, for both personal and academic inquiries, is the investigation of various cultural and sub-cultural groups and their experiences. The rituals and performance customs of particular modern and indigenous communities offers an intriguing glimpse into worlds I have yet to travel. I will briefly discuss my previous adventures with international travel, religious and spiritual quests, and my examination of a multitude of artistic and cultural genres like theatre and dance. Both my previous cultural experiences and the performance elements of cross- cultural studies directly influenced my choreography while in the School of Dance at Ohio University. -

Corporation Fonds

The Corporation fonds Compiled by Cobi Falconer (2005) and Tracey Krause (2005, 2006) University of British Columbia Archives Table of Contents Fonds Description o Title / Dates of Creation / Physical Description o Administrative History o Scope and Content o Notes Series Descriptions o Research o Correspondence o Pre-Production o Production . Transcriptions o Post-Production o Audio/Video tapes o Photographs File List Catalogue entry (UBC Library catalogue) Fonds Description The Corporation fonds. - 1994-2004. 2.03 m of textual material. 904 video cassette tapes. 10 audio cassette tapes. 12 photographs. Administrative History The Corporation, a film released in 2004, is a ground breaking movie documentary about the identity, economic, sociological, and environmental impact of the dominant and controversial institution of corporations. Based on the book The Corporation: The Pathological Pursuit of Profit and Power by Joel Bakan, the film portrays corporations as a legal person and how this status has contributed to their rise in dominance, power, and unprecedented wealth in Western society. The Corporation exposes the exploitation of corporations on democracy, the planet, the health of individuals which is carried out through case studies, anecdotes, and interviews. The documentary includes 40 interviews of CEOs, critics, whistle blowers, corporate spies, economists, and historians to further illuminate the "true" character of corporations. The Corporation was the conception of co-creator, Vancouver based, Mark Achbar; and co-creator, associate producer, and writer Joel Bakan. The film, coordinated by Achbar and Jennifer Abbott and edited by Abbott has currently received 26 international awards, and was awarded the winner of the 2004 Sundance Audience Award and Best Documentary at the 2005 Genie Awards. -

The Corporation: the Pathological Pursuit of Profit and Power Ebook, Epub

THE CORPORATION: THE PATHOLOGICAL PURSUIT OF PROFIT AND POWER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Joel Bakan | 272 pages | 23 Jun 2005 | Little, Brown Book Group | 9781845291747 | English | London, United Kingdom The Corporation: The Pathological Pursuit of Profit and Power PDF Book Sort order. View 1 comment. I cannot believe that these corporations get away with so much even after violating human rights on daily basis. Today, I'm giving it five stars because it is a succinct summary of what I know and believe about the institution of corporation, and because it is presented and backed up fantastically. View all 7 comments. Finally, something that is not really a complaint, but more an observation: this book was published in Complaint two: no consideration of contradictory evidence. This is what I gained from reading this short book. This book was an eye-opening and overall good read. This results in a pattern of social costs imposed by bsuiness in exchange for private gains for its executives and owners. Some of my favorite phrases were: "market fundamentalism and its facilitation of deregulation and privatization," "the expanding role of the state in protecting corporations from citizens," "socialism for the rich and capitalism for the poor," "rationalized greed and mandated selfishness," and "the co-optation of government by business. In what Simon and Schuster describes as "the most revolutionary assessment of the corporation since Peter Drucker's early works", The Corporation makes the following claims:. Through vignettes and interviews, The Corporation examines and criticizes corporate business practices. How can we keep better eyes on the corporations that impact our society? Bakan includes these among his remedies on pages Granted, while I may not own a car, and resist the temptation to buy things that I do not need, I still live a rather luxurious life, and the fact that I can jump on a plane and fly to Europe and back, is a testament to that. -

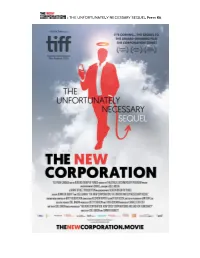

THE UNFORTUNATELY NECESSARY SEQUEL Press

: THE UNFORTUNATELY NECESSARY SEQUEL Press Kit : THE UNFORTUNATELY NECESSARY SEQUEL Press Kit Logline The Corporation examined an institution within society; The NEW CORPORATION reveals a society now fully remade in the corporation's image, tracking devastating consequences and also inspiring movements for change. Short Synopsis (50 words) The Corporation (2003) examined an institution within society; The New Corporation reveals a world now fully remade in the corporation's image, perilously close to losing democracy. We trace the devastating consequences, connecting the dots between then and now, and inspire with stories of resistance and change from around the world. Short Synopsis (100 words) From Joel Bakan and Jennifer Abbott, filmmakers of the multi-award-winning global hit, The Corporation, comes this hard-hitting and timely sequel. The New Corporation reveals how the corporate takeover of society is being justified by the sly rebranding of corporations as socially conscious entities. From gatherings of corporate elites in Davos, to climate change and spiralling inequality; the rise of ultra-right leaders, to Covid-19 and racial injustice, the film looks at corporations' devastating power. In the face of inequality, climate change, and the hollowing out of democracy The New Corporation is a cry for social justice, democracy, and transformative solutions. Synopsis (125 words) From Joel Bakan and Jennifer Abbott, filmmakers of the multi-award-winning global hit, The Corporation, comes this hard-hitting and timely sequel. The New Corporation reveals how the corporate takeover of society is being justified by the sly rebranding of corporations as socially conscious entities. From gatherings of corporate elites in Davos, to climate change and spiralling inequality; the rise of ultra-right leaders to Covid-19 and racial injustice, the film looks at corporations' devastating power. -

Media Studies 11-12 Textbook

Media Study Guides by Teachers in EDCP 481 Table of Contents Identity & Culture 1. Ma Vie en Rose (Lucas Mann & Marie-Anne Hellinckx) 2. Mean Girls (Chelsea Campbell & Michelle Fatkin) 3. Little Miss Sunshine (Chris Howey & Yik Wah Penner) 4. A Warrior’s Religion (Paramjit Koka & Rupinder Grewal) 5. Thirteen (Kelly Skehill & Kat Ast) 6. 16 and Pregnant (Thomas Froh & Peter Maxwell) 7. My Sister’s Keeper (Stephanie Malloy & Jon Schmidt) 8. One Week (Ashley MacKenzie & Alex Thureau) 9. Schindler’s List (Paul Eberhardt & Rhonda Lochhead) 10. Family Guy & The Simpsons (Amerdeep Nann & Ashley Bayles) 11. Bright Star (Mark Brown) 12. Freedom Writers (Grace Woo & Chris Flannelly) 13. Schindler’s List (Jennifer Olson, Jenn Mansour & Sarah Kharikian) 14. The Television Family (Melissa Evans & Shaun Beach) Culture, Fiction, Power, and Politics 15. Lord of the Rings (Lance Peters & Alex McKillop) 16. The Dark Knight (Adam Deboer & Alvin Lui) 17. Advertising & the End of the World (Safi Arnold & Zachary Pinette) 18. The Office (Fay Sterne & Brittaney Boone) 19. The Corporation (Michael Wuensche & John Ames) 20. Outsourced (Michael Bui & Jennifer Neff) 21. Food Inc. (Liilian Ryan & Sarah James) 22. Mad Men (Graham Haigh & Dean Morris) Environment, Ecology, and Reality 23. Avatar (Wendy Sigaty & Haley Lucas) 24. Wall-e (Rachel Fales & Jennifer Visser) 25. Into the Wild (Kady Huhn and Hannah Yu) 26. Wall-e (Kara Troke and Taha Anjarwalla) 27. 127 Hours (Nick De Santis & Nam Pham) 28. Lost (Dianna Stashuk and Adam Alvaro) Music and Gaming Culture 29. Where is the Love? (Stef Dubrowski & Jess Lee) 30. Popular Music and Videos (Alexander McKechnie) 31. -

The Corporation the Pathological Pursuit of Profit and Power By: Joel Bakan ISBN: 0743247469 See Detail of This Book on Amazon.Com

The Corporation The Pathological Pursuit of Profit and Power By: Joel Bakan ISBN: 0743247469 See detail of this book on Amazon.com Book served by AMAZON NOIR (www.amazon-noir.com) project by: PAOLO CIRIO paolocirio.net UBERMORGEN.COM ubermorgen.com ALESSANDRO LUDOVICO neural.it Page 1 Introduction As images of disgraced and handcuffed corporate executives parade across our television screens, pundits, politicians, and business leaders are quick to assure us that greedy and corrupt individuals, not the system as a whole, are to blame for Wall Street's woes. "Have we just been talking about some bad apples?" Sam Donaldson recently asked former New York Stock Exchange chief Richard Grasso on ABC's This Week, "or is there something in the system that is broken?" "Well, Sam," Grasso explained, "we've had some massive failures, and we've got to root out the bad people, the bad practices; and certainly, whether the number is one or fifteen, that's in comparison to more than ten thousand publicly traded corporations-but one, Sam, just one WorldCom or one Enron, is one too many." Despite such assurances , citizens today-and many business leaders too-are concerned that the faults within the corporate system run much deeper than a few tremors on Wall Street would indicate. These larger concerns are the focus of this book. A key premise is that the corporation is an institution-a unique structure and set of imperatives that direct the actions of people within it. It is also a legal institution, one whose existence and capacity to operate depend upon the law. -

A Provocative, Entertaining, and at Times Chilling Documentary.” – Indiwire

From the co-director of MANUFACTURING CONSENT “A provocative, entertaining, and at times chilling documentary.” – IndiWIRE Winner of 16 International Awards PRESS CONTACT: Released in Australia by DISTRIBUTOR CONTACT: Teri Calder Gil Scrine Films 4 Moore Street 44 Northcote Street Bondi NSW 2026 East Brisbane QLD 4169 Tel/Fax: 02 9130 6153 Tel: 07 3391 0124 Mob: 0425 230 679 Fax: 07 3391 0154 [email protected] Mob: 0418 596 482 Email:[email protected] www.gilscrinefilms.com.au One hundred and fifty years ago, the corporation was a relatively insignificant entity. Today, it is a vivid, dramatic and pervasive presence in all our lives. Like the Church, the Monarchy and the Communist Party in other times and places, the corporation is today’s dominant institution. But history humbles dominant institutions. All have been crushed, belittled or absorbed into some new order. The corporation is unlikely to be the first to defy history. In this complex, exhaustive and highly entertaining documentary, Mark Achbar, co-director of the influential and inventive MANUFACTURING CONSENT: NOAM CHOMSKY AND THE MEDIA, teams up with co-director Jennifer Abbott and writer Joel Bakan to examine the far-reaching repercussions of the corporation’s increasing preeminence. Based on Bakan’s book THE CORPORATION: THE PATHOLOGICAL PURSUIT OF PROFIT AND POWER, the film is a timely, critical inquiry that invites CEOs, whistle-blowers, brokers, gurus, spies, players, pawns and pundits on a graphic and engaging quest to reveal the corporation’s inner workings, curious history, controversial impacts and possible futures. Featuring illuminating interviews with Noam Chomsky, Michael Moore, Howard Zinn and many others, THE CORPORATION charts the spectacular rise of an institution aimed at achieving specific economic goals as it also recounts victories against this apparently invincible force. -

Principles of the Corporation Give It a Highly Anti-Social “Personality”: It Is

150 years ago, the corporation was a relatively insignificant institution. Today, it is a vivid, dramatic, and pervasive presence in all our lives. Like the Church, the Monarchy and the Communist Party in other times and places, the corporation is today's dominant institution. But history humbles dominant institutions. All have been crushed, belittled or absorbed into some new order. The corporation is unlikely to be the first to defy history. A timely, critical inquiry, THE CORPORATION invites players, pawns and pundits on a graphic and engaging quest to reveal the corporation’s inner workings, curious history, controversial impacts and possible futures. Case studies, anecdotes and true confessions reveal behind-the-scenes tensions and influences in several corporate and anti-corporate dramas. Each illuminates an aspect of the corporation’s complex character. Among the 42 interview subjects are CEOs and top-level executives from a range of industries: oil, pharmaceutical, computer, tire, manufacturing, public relations, branding, advertizing and undercover marketing; in addition, a Nobel-prize winning economist, the first management guru, a corporate spy, and a range of academics, critics, historians and thinkers. (for details, please see separate file: Who’s Who in The Corporation.) A LEGAL “PERSON” In the mid-1800s the corporation emerged as a legal ”person”. Imbued with a “personality” of pure self-interest, the next 100 years saw the corporation’s rise to dominance. The corporation created unprecedented wealth. But at what cost? The remorseless rationale of “externalities”—as Milton Friedman explains: the unintended consequences of a transaction between two parties on a third—is responsible for countless cases of illness, death, poverty, pollution, exploitation and lies. -

HOW the BRAIN SCIENCES CAN INFORM SOCIAL JUSTICE STRATEGIES by MARC ANDREW BRILLINGER a THESIS SUBMITTED in PARTI

BRAINSTORMING: HOW THE BRAIN SCIENCES CAN INFORM SOCIAL JUSTICE STRATEGIES by MARC ANDREW BRILLINGER A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Doctor of Philosophy in THE COLLEGE OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Interdisciplinary Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Okanagan) November 2014 © Marc Andrew Brillinger, 2014 Abstract Anthropogenic climate disruption (global warming) and income inequality are in the process of spiraling out of control, pushing humanity to the brink of global collapse and mass extinction of species. Underlying this profound issue is an epic struggle taking place between two alternate worldviews. Corporate institutional power has morphed economics, capitalism and the ―free market‖ into a suicide machine that increasingly extracts, exploits and selfishly hordes the bulk of the world‘s wealth for the few. The obscene wealth and power of the plutocrats and oligarchs has rigged both economics and politics to benefit the one percent and destroy the environment. Alternately, social justice led by activists have made valiant attempts to slow down this process and regain some sanity with a return to community, sociality and cooperation. A world worth living in hangs precariously in the balance. This interdisciplinary research focuses on the critical, yet unexplored, intersection of social justice and the burgeoning brain sciences. The ―brain sciences‖ refers to the rapidly increasing interdisciplinary understanding (from neuroscience, biology, social sciences etc.) of the human brain, mind, consciousness and their relationship to institutions, cultures, society and human belief and behaviour. A synthesis of the knowledge arising out of the brain sciences, as it applies to existing social activist strategies and tactics, now seems a necessity in the attempt to restrain corporate institutional power that is currently running amok in North America and globally. -

The Corporation As Person and Psychopath: Multimodal Metaphor, Rhetoric and Resistance

The Corporation as Person and Psychopath: Multimodal Metaphor, Rhetoric and Resistance Copyright © 2013 Critical Approaches to Discourse Analysis across Disciplines http://cadaad.net/journal Vol. 6 (2): 114 – 136 ISSN: 1752-3079 ARRAN STIBBE University of Gloucestershire [email protected] Abstract This article conducts a detailed analysis of multimodal metaphor in the documentary film The Corporation, with particular focus on the metaphor THE CORPORATION IS A PERSON. The metaphors that make up the film are analysed within the immediate context of the rhetorical structure of the film, the discursive context of the use of THE CORPORATION IS A PERSON metaphor by corporations to gain power, and the background context of THE CORPORATION IS A PERSON as a ubiquitous conceptual metaphor in everyday cognition. The metaphors in the film are then compared with other multimodal metaphors from two protest videos. The article can be thought of as Positive Discourse Analysis, in that the use of metaphors in the film and videos is held up as an example of how multimodal media can be used to resist hegemonic discourses that harm people and the environment. A practical aim of the analysis is to reveal the detailed workings of the metaphors in order to provide resources that can be drawn on in the construction of effective materials for challenging hegemonic constructions of the corporation in the future. Key words: multimodal metaphor, corporate personhood, positive discourse analysis, rhetoric 1. Introduction This is an article about a metaphor, one that plays an important role in the structuring of contemporary industrial society and one which, according to those who resist it, causes great harm to both people and the environment. -

1 Court File No. ONTARIO SUPERIOR COURT of JUSTICE BETWEEN

Court File No. ONTARIO SUPERIOR COURT OF JUSTICE BETWEEN JOEL BAKAN First Applicant and COOL WORLD TECHNOLOGIES, INC. Second Applicant and GRANT STREET PRODUCTIONS Third Applicant and ETHEL KATHERINE DODDS Fourth Applicant and CANADA Respondent APPLICATION UNDER RULE 14.05 OF THE RULES OF CIVIL PROCEDURE NOTICE OF APPLICATION TO THE RESPONDENTS A LEGAL PROCEEDING HAS BEEN COMMENCED by the Applicant. The claim made by the Applicant appears on the following page. THIS APPLICATION will come on for a hearing on , at 10:00 am, at 393 University Avenue, 10th Floor, Toronto ON, M5G 1E6. 1 IF YOU WISH TO OPPOSE THIS APPLICATION, to receive notice of any step in the application or to be served with any documents in the application you or an Ontario lawyer acting for you must forthwith prepare a notice of appearance in Form 38A prescribed by the Rules of Civil Procedure, serve it on the Applicant’s lawyer or, where the Applicant does not have a lawyer, serve it on the Applicant, and file it, with proof of service, in this court office, and you or your lawyer must appear at the hearing. IF YOU WISH TO PRESENT AFFIDAVIT OR OTHER DOCUMENTARY EVIDENCE TO THE COURT OR TO EXAMINE OR CROSS-EXAMINE WITNESSES ON THE APPLICATION, you or your lawyer must, in addition to serving your notice of appearance, serve a copy of the evidence on the Applicant’s lawyer or, where the Applicant does not have a lawyer, serve it on the Applicant, and file it, with proof of service, in the court office where the application is to be heard as soon as possible, but at least four days before the hearing. -

From the Co-Director of MANUFACTURING CONSENT “A Provocative, Entertaining, and at Times Chilling Documentary.” – Indiwire

From the co-director of MANUFACTURING CONSENT “A provocative, entertaining, and at times chilling documentary.” – IndiWIRE Winner of 26 International Awards One hundred and fifty years ago, the corporation was a relatively insignificant entity. Today, it is a vivid, dramatic and pervasive presence in all our lives. Like the Church, the Monarchy and the Communist Party in other times and places, the corporation is today’s dominant institution. But history humbles dominant institutions. All have been crushed, belittled or absorbed into some new order. The corporation is unlikely to be the first to defy history. In this complex, exhaustive and highly entertaining documentary, Mark Achbar, co-director of the influential and inventive MANUFACTURING CONSENT: NOAM CHOMSKY AND THE MEDIA, teams up with co-director Jennifer Abbott and writer Joel Bakan to examine the far-reaching repercussions of the corporation’s increasing preeminence. Based on Bakan’s book THE CORPORATION: THE PATHOLOGICAL PURSUIT OF PROFIT AND POWER, the film is a timely, critical inquiry that invites CEOs, whistle-blowers, brokers, gurus, spies, players, pawns and pundits on a graphic and engaging quest to reveal the corporation’s inner workings, curious history, controversial impacts and possible futures. Featuring illuminating interviews with Noam Chomsky, Michael Moore, Howard Zinn and many others, THE CORPORATION charts the spectacular rise of an institution aimed at achieving specific economic goals as it also recounts victories against this apparently invincible force. www.thecorporation.com 2 Media Praise For THE CORPORATION “Coolheaded and incisive...thorough and informative... It leaves audiences with a cold shiver!” -San Francisco Chronicle “Compelling and entertaining....likely to stir the sensibilities of anyone with a conscience greater than a flytrap and amuse anybody born with a funny bone...check it out and pass the word.” -San Francisco Examiner “Brilliant.