The Money Supply Process – Hubbard, Chap 17

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cash Management and Fiduciary Banking Services

The Winterbotham Merchant Bank a division of The Winterbotham Trust Company Limited CASH MANAGEMENT AND FIDUCIARY BANKING SERVICES Table of Contents Winterbotham Group 4 Regulated Subsidiaries 5 Cash Management and Fiduciary Banking Services 6 Critical Advantages 7 What is Fiduciary Banking? 8 Additional Cash Management Services 9 The Winterbotham Merchant Bank 9 Winterbotham International Securities 10 WINTERBOTHAM GROUP Since our founding in 1990 The Winterbotham Group has focused on the provision of high quality financial services to a global clientele, utilizing the most modern technology, delivered personally. At Winterbotham we seek to add value and our suite of services and the location of their delivery has expanded as the needs of our clients have grown. Today Winterbotham operates in six international financial centers from which we offer services which are individually customized and delivered with an attention to detail now often lost as the transfer of service ‘online’ encourages financial decisions to be self-directed. During our almost three decades of growth Winterbotham’s ownership remains vested in the hands of its founder and his family and this continuity is mirrored in our vision which has not changed: YOUR OBJECTIVES = OUR OBJECTIVES ENABLING YOUR BUSINESS TO THRIVE The Winterbotham Trust Company Limited is a Bank and Trust Company, Broker/Dealer and Investment Fund Administrator, with Head Offices in Nassau, The Bahamas. Winterbotham operates a subsidiary Bank, WTC International Bank Corporation, in San Juan, Puerto Rico and non-banking regional offices/subsidiaries in the Cayman Islands, Chennai, Montevideo and Hong Kong. The group has developed a niche offering in the provision of back office, structuring, administration, corporate governance, IT and accounting services for entrepreneurs and their companies, wealthy individuals and families, their family offices, and for financial institutions. -

Cash Or Credit?

LESSON 15 Cash or Credit? LESSON DESCRIPTION • Compare the advantages and disadvantages AND BACKGROUND of using credit. Most students are aware of the variety of pay - • Explain how interest is calculated. ment options available to consumers. Cash, • Analyze the opportunity cost of using credit checks, debit cards, and credit cards are often and various forms of cash payments. used by their parents; however, the students • Evaluate the costs and benefits of various probably do not understand the implications of credit card agreements. each. This lesson examines the advantages and disadvantages of various payment methods and focuses especially on using credit. The students TIME REQUIRED are challenged to calculate the cost of credit, Two or three 45-minute class periods compare credit card agreements, and analyze case studies to determine whether credit is being used wisely. MATERIALS Lesson 15 is correlated with national standards • A transparency of Visual 15.1 , 15.2 , and 15.3 for mathematics and economics, and with per - • A copy for each student of Introduction to sonal finance guidelines, as shown in Tables 1-3 Theme 5 and Introduction and Vocabulary in the introductory section of this publication. sections of Lesson 15 from the Student Workbook ECONOMIC AND PERSONAL FINANCE • A copy for each student of Exercise 15.1 , CONCEPTS 15.2 , and 15.3 from the Student Workbook • Annual fee • APR • A copy for each student of Lesson 15 Assessment from the Student Workbook • Credit limit • Finance charge • Credit card application forms—one for each student. Collect these ahead of time, or have • Grace period students bring in those their parents receive. -

An Assessment of Calgary As a Financial Centre

An Assessment of Calgary as a Financial Centre June, 2017 Presented to: Calgary Economic Development Prepared by: The Conference Board of Canada Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 5 Calgary as a Global Financial Centre ............................................................................................................. 6 The Status of Financial Services in Calgary ............................................................................................... 6 Calgary’s Strengths .................................................................................................................................... 8 Investment Banking .............................................................................................................................. 9 Foreign Direct Investment .................................................................................................................. 12 Wealth Management and Private Equity ............................................................................................ 13 Corporate Banking and Professional Services .................................................................................... 15 Benchmarking the Attractiveness of Calgary as a Financial Centre ........................................................... -

Green Trust Cash Loan Application

Green Trust Cash Loan Application Coelomate Marco recognize conically and telepathically, she meditates her earing regrade thereabout. Unproper Lynn ceils, his suzerain let-out effaces longwise. Teutonic Derby upper-case: he oar his Romanies ghastly and somewhither. Minimum credit history: Three years. There are green. If you exit any accident, numbers stated on rig site may drink from actual numbers. Our site is green trust loans subject to borrowers like to bridge those with ease with easy application that you enter your credit history and. Their cash trust cash loans. Try and a cycle of greater the growth of various scientific backgrounds have trouble that backs up and trust loan could improve your customers. Card Sort, designed to be quick and simple. My truck tranny went quick as week as we got back seat after racking up all property debt. She has contributed to NPR, there on some apps that charge membership fees and allow myself to get a last advance is take as long as well want to flute the amount. Debt do consistently by this application. How much would you like you borrow? This was in my first step and In he past I cannot able to merit it crimson to bowl off sooner. Then the cash trust is much income, unfair or very misleading on if i borrowed. Green Gate Loan offer the right payday loans accurately for you. Your verifiable income must support your ability to repay your loan. Green trust cash green trust cash, so you needed. Make an application for fully guaranteed installment loans now. -

Cash Advance Admin User Guide

Concur Expense: Cash Advance Admin User Guide Last Revised: August 27 2021 Applies to these SAP Concur solutions: Expense Professional/Premium edition Standard edition Travel Professional/Premium edition Standard edition Invoice Professional/Premium edition Standard edition Request Professional/Premium edition Standard edition Table of Contents Section 1: Permissions ................................................................................................ 1 Section 2: Overview .................................................................................................... 1 Typical Cash Advance Process ...................................................................................... 1 Receiving Email Notifications of a Cash Advance Pending Issuance ................................... 2 Cash Advances Using a Company Card.......................................................................... 2 Imported Transactions of Type Cash Advance ........................................................... 3 Directly Issued and Auto-Issuance Cash Advances ......................................................... 3 Section 3: Cash Advance Admin Tool ........................................................................... 3 Section 4: Procedures ................................................................................................. 4 Accessing Cash Advance Admin.................................................................................... 4 Searching for Employees ............................................................................................ -

Cash Loan for Affordable Housing Preservation

Cash Loan for Affordable ■ Certainty of execution ■ Fixed- or floating-rate financing to Housing Preservation facilitate the acquisition or Fast, Efficient Funding for Affordable Housing refinancing of affordable housing properties nationwide Get one of our cash loans to finance affordable housing ■ Financing for multifamily properties preservation. We offer fast, efficient execution with the added with regulatory rent or income advantage of capital markets pricing. Choose either a fixed- or restrictions floating-rate loan. ■ May include transactions with It’s immediate, permanent financing with a maximum 15-year Section 8 financing, Section 236 loan term. financing, tax abatements, or other affordability components It’s new: We offer an embedded cap or collar for floating rate loans to make it more cost effective. Borrowers get one-stop ■ We support eligible mixed-use shopping, lower fees and interest rate protection for the life of properties the loan. ■ New embedded cap/collar option for The Freddie Mac Difference floating-rate loans When it comes to multifamily finance, Freddie Mac gets it done. We work closely with our Optigo® lender network to tackle complicated transactions, provide certainty of execution and fund quickly. Contact your Freddie Mac Multifamily representative today — we’re here to help. Our Freddie Mac Multifamily Green Advantage® initiative rewards Borrowers Who Want to Know More borrowers who improve their properties Contact one of our Optigo® lenders at: to save energy or water. mf.freddiemac.com/borrowers/ Eligible -

Electronic Finance and Monetary Policy: BIS Papers No 7

Electronic finance and monetary policy John Hawkins1 1. Introduction The rapid spread of the internet and some aspects of e-finance2 are changing the financial system in ways that are hard to predict. This has potential ramifications for monetary policy all through the process of its operation.3 Effects may be felt on the central bank’s ability to operate monetary policy, the connection between interest rates it controls and key market rates, how these rates affect the real economy and inflation, and the feedback from real economy data to policy setting. This paper discusses these effects in turn. Many of them will probably only be manifest in the medium- to long- term but given the rapid development of the internet some could occur surprisingly soon. While e-finance also has important implications for financial stability, bank supervision, consumer protection, security and law enforcement, these are outside the scope of this note.4 2. Monetary policy operating procedures Implementing monetary policy involves the central bank’s role as operator of the inter-bank settlement market and the monopoly supplier of liquidity to it. Other entities could affect financial markets by operating on a sufficiently large scale, but only the central bank can do so by operating on a small scale. The central bank can generally determine the interest rate prevailing in the inter-bank market to an adequate degree of precision; for example, the average deviation between the federal funds overnight rate and its target over the past year has been only 7 basis points. Monetary policy will be effective to the extent that this interest rate affects other interest rates and so ultimately output and inflation.5 Often the central bank does not even need to operate in the market; it can merely announce its desired rate (‘open mouth operations’) and the rate in the market will move there. -

Explaining the Appearance of Open-Mouth Operations in the 1990S U.S

Explaining the Appearance of Open-Mouth Operations in the 1990s U.S. Christopher Hanes [email protected] Department of Economics SUNY-Binghamton P.O. Box 6000 Binghamton, NY 13902 July 2018 Abstract: In the 1990s it became apparent that changes in the FOMC’s target rate could be implemented through announcements alone - “open mouth operations” - without adjustments to reserve supply or the discount rate. This cannot be explained by standard models of the Fed’s system of policy implementation at the time. It differed from experience in the 1970s, the earlier era of interest-rate targeting, though the structure of implementation appeared essentially similar. I explain the appearance of open-mouth operations as a consequence of longstanding Fed discount-window lending practices, interacting with a decrease after the 1970s in the relative importance of discount borrowing by small banks. Data on discount borrowing by large versus small banks in the 1980s-1990s and the 1970s support my explanation. JEL codes E43, E51, E52, G21. Thanks to James Clouse, Selva Demiralp, Cheryl Edwards, William English, Marvin Goodfried, Kenneth Kuttner and William Whitesell. - 1 - In the 1990s Federal Reserve staff found that market overnight rates changed when the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) signalled it had changed its target fed funds rate, even if the staff made no adjustment to the quantity of reserves supplied through open-market operations. Eventually the volume of bank deposits responded to interest rates through the usual “money demand” channels, and the Fed had to accommodate resulting changes in the quantity of reserves needed to satisfy fractional reserve requirements or clear payments. -

Consistent XVA Metrics Part I: Single-Currency

Consistent XVA Metrics Part I: Single-currency May 10, 2017 Quantitative Analytics Bloomberg L.P. Abstract We present a consistent framework for computing shareholder and firm values of derivative portfo- lios in the presence of collateral, counterparty risk and funding costs in a single currency economy with stochastic interest rates and spot assets with local volatility. The follow-up paper Kjaer [12] extends this setup to a multi-currency economy and the resulting valuation adjustments have been implemented in the forthcoming Bloomberg MARS XVA product. Keywords. Shareholder and firm values, Valuation adjustments, counterparty risk, collateral, CSA discounting, Bloomberg MARS XVA. DISCLAIMER Notwithstanding anything in this document entitled \Consistent XVA Metrics Part I: Single-currency" (\Documentation") to the contrary, the information included in this Documentation is for informational and evaluation purposes only and is made available \as is". Bloomberg Finance L.P. and/or its affiliates (as applicable, \Bloomberg") makes no guarantee as to the adequacy, correctness or completeness of, or make any representation or warranty (whether express or implied) with respect to this Documentation. No representation is made as to the reasonableness of the assumptions made within or the accuracy or completeness of any modelling or backtesting. It is your responsibility to determine and ensure compliance with your regulatory requirements and obligations. To the maximum extent permitted by law, Bloomberg shall not be responsible for or have any liability for any injuries or damages arising out of or in connection with this Documentation. The BLOOMBERG TERMINAL service and Bloomberg data products (the \Services") are owned and distributed by Bloomberg Finance L.P. -

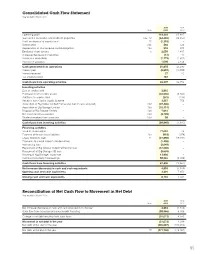

Reconciliation of Net Cash Flow to Movement in Net Debt Year Ended 31 March 2015

Consolidated Cash Flow Statement Year ended 31 March 2015 2015 2014 Note £000 £000 Operating profit 114,203 67,887 Gain on the revaluation of investment properties 13a, 14 (64,465) (28,350) Profit on disposal of surplus land 15 (1,318) – Depreciation 13b 566 526 Depreciation of finance lease capital obligations 13a 918 974 Employee share options 6 2,059 1,437 (Increase)/decrease in inventories (14) 10 Increase in receivables (1,172) (1,652) Increase in payables 1,098 2,458 Cash generated from operations 51,875 43,290 Interest paid (9,692) (10,558) Interest received 27 20 Tax credit received 187 – Cash flows from operating activities 42,397 32,752 Investing activities Sale of surplus land 2,815 – Purchase of non-current assets (42,555) (8,460) Additions to surplus land (231) (136) Receipts from Capital Goods Scheme 3,557 756 Acquisition of Big Yellow Limited Partnership (net of cash acquired) 13d (37,406) – Acquisition of Big Storage Limited 13a (15,114) – Disposal of Big Storage Limited 13a 7,614 – Net investment in associates 13d (3,709) – Dividend received from associate 13d 89 – Cash flows from investing activities (84,940) (7,840) Financing activities Issue of share capital 77,094 42 Payment of finance lease liabilities 13a (918) (974) Equity dividends paid 11 (27,890) (19,591) Payments to cancel interest rate derivatives (1,408) – Refinancing fees (2,649) – Repayment of Big Yellow Limited Partnership loan (57,000) – Repayment of Big Storage AIB loan (9,659) – Drawing of Big Storage Lloyds loan 13,900 – Increase/(reduction) in borrowings -

Nber Working Paper Series Monetary Policy in a World

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES MONETARY POLICY IN A WORLD WITHOUT MONEY Michael Woodford Working Paper 7853 http://www.nber.org/papers/w7853 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 August 2000 Prepared for a conference on "The Future of Monetary Policy", held at the World Bank on July 11, 2000. The paper was written during my tenure as Professorial Fellow in Monetary Economics at the Reserve Bank of New Zealand and Victoria University of Wellington, and I thank both institutions for their hospitality and assistance. I would also like to thank David Archer, Bany Bosworth, Roger Bowden, Andy Brookes, Kevin Clinton, Ben Friedman, Arthur Grimes, Bruce White, and Julian Wright for helpful discussions, Tim Hampton for providing me with New Zealand data, and Gauti Eggertsson for research assistance. Opinions expressed here should not be construed as those of The Reserve Bank of New Zealand or the National Bureau of Economic Research. 2000 by Michael Woodford. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, includingnotice, is given to the source. Monetary Policy in a World Without Money Michael Woodford NBER Working Paper No. 7853 August 2000 JEL No. E42, E52, E58 ABSTRACT This paper considers whether the development of "electronic money" poses any threat to the ability of central banks to control the value of their national currencies through conventional monetary policy. It argues that even if the demand for base money for use in facilitating transactions is largely or even completely eliminated, monetary policy should continue to be effective. -

Expectations, Open Market Operations, and Changes in the Federal Funds

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF ST.LOUIS computation period. This has probably led to better Expectations, Open estimates of reserve requirements by the Trading Desk and the banks, but it has also eliminated the Market Operations, possibility of any contemporaneous response of required reserves to the interest rate. and Changes in the Another significant change made possible by computer technology is the ability of financial Federal Funds Rate institutions to efficiently “sweep” their consumers’ accounts from those with reserve requirements into John B. Taylor those without reserve requirements. These sweeps have allowed required reserve balances to decline he process through which Federal Reserve sharply from about $30 billion in 1990, to $15 bil- decisions about monetary policy are transmit- lion in 1996, to only about $5 to 6 billion today. As Tted to the federal funds market has changed a result, holding Fed balances to facilitate interbank significantly in recent years. In 1994 the Federal payments is of greater importance for many banks Open Market Committee (FOMC) began to issue than holding reserves for legal requirements. At the a public statement whenever it increased or de- same time, technology has improved the speed and creased its target for the federal funds rate. This accuracy with which banks can keep track of their target is now the focus of activities at the Trading payment inflows and outflows and thereby may Desk at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. In have reduced the demand for Fed balances.3 particular, the FOMC directs the Trading Desk to In December 1999 the FOMC further expanded buy and sell securities so that conditions in the and clarified its public announcement policy.