House of Hospitality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Balboa Park Committee Meeting | APRIL 7, 2016 Workshop Item Attachments

Balboa Park Committee Meeting | APRIL 7, 2016 Workshop Item Attachments Project: Renovation + Addition to Mingei International Museum Location: House of Charm, Balboa Park Architect: LUCE et Studio Architects, Inc. Balboa Park Committee Meeting | APRIL 7, 2016 Workshop Item Attachments Project: Renovation + Addition to Mingei International Museum Location: House of Charm, Balboa Park Architect: LUCE et Studio Architects, Inc. PROJECT SCOPE + ASPIRATIONS A.) Open the museum to the Park Augment existing entries to provide additional access to a Civic Living Room for Park and the City. A full museum floor of galleries, a library, store, restaurant, education space, and sculpture court free and open to the public. Plaza de Panama Alcazar Garden PLAZA LEVEL not to scale N Balboa Park Committee Meeting | APRIL 7, 2016 Workshop Item Attachments Project: Renovation + Addition to Mingei International Museum Location: House of Charm, Balboa Park Architect: LUCE et Studio Architects, Inc. PROJECT SCOPE + ASPIRATIONS B.) A new interior multipurpose space A flexible multipurpose space for lectures, films, dinners, and other events fills in the existing, non-functional loading dock space. COLLABORATIVE LEVEL not to scale N Balboa Park Committee Meeting | APRIL 7, 2016 Workshop Item Attachments Project: Renovation + Addition to Mingei International Museum Location: House of Charm, Balboa Park Architect: LUCE et Studio Architects, Inc. PROJECT SCOPE + ASPIRATIONS C.) Add public landscape space at the sculpture court A Sculpture Court above the multipurpose space provides a new public niche to find repose within the park. In addition, the sculpture court opens directly to the Plaza level and cafe and can be used for private events and the installation of temporary exhibitions. -

Arciiltecture

· BALBOA PARK· CENTRAL MESA PRECISE PLAN Precise Plan • Architecture ARCIIlTECTURE The goal of this section is to rehabilitate and modify the architecture of the Central Mesa ina manner which preserves its historic and aesthetic significance while providing for functional needs. The existing structures built for the 1915 and the 1935 Expositions are both historically and architecturally significant and should be reconstructed or rehabilitated. Not only should the individual structures be preserved, but the entire ensemble in its original composition should be preserved and restored wherever possible. It is the historic relationship between the built and the outdoor environment that is the hallmark of the two Expositions. Because each structure affects its site context to such a great degree, it is vital to the preservation of the historic district that every effort be made to preserve and restore original Exposition building footprints and elevations wherever possible. For this reason, emphasis has been placed on minimizing architectural additions unless they are reconstructions of significant historical features. Five major types of architectural modifications are recommended for the Central Mesa and are briefly described below. 1. Preservation and maintenance of existing structures. In the case of historically significant architecture, this involves preserving the historical significance of the structure and restoring lost historical features wherever possible. Buildings which are not historically significant should be preserved and maintained in good condition. 2. Reconstructions . This type of modification involves the reconstruction of historic buildings that have deteriorated to a point that prevents rehabilitation of the existing structure. This type of modification also includes the reconstruction of historically significant architectural features that have been lost. -

Casa Del Prado in Balboa Park

Chapter 19 HISTORY OF THE CASA DEL PRADO IN BALBOA PARK Of buildings remaining from the 1915 Panama-California Exposition, exhibit buildings north of El Prado in the agricultural section survived for many years. They were eventually absorbed by the San Diego Zoo. Buildings south of El Prado were gone by 1933, except for the New Mexico and Kansas Buildings. These survive today as the Balboa Park Club and the House of Italy. This left intact the Spanish-Colonial complex along El Prado, the main east-west avenue that separated north from south sections The Sacramento Valley Building, at the head of the Plaza de Panama in the approximate center of El Prado, was demolished in 1923 to make way for the Fine Arts Gallery. The Southern California Counties Building burned down in 1925. The San Joaquin Valley and the Kern-Tulare Counties Building, on the promenade south of the Plaza de Panama, were torn down in 1933. When the Science and Education and Home Economy buildings were razed in 1962, the only 1915 Exposition buildings on El Prado were the California Building and its annexes, the House of Charm, the House of Hospitality, the Botanical Building, the Electric Building, and the Food and Beverage Building. This paper will describe the ups and downs of the 1915 Varied Industries and Food Products Building (1935 Food and Beverage Building), today the Casa del Prado. When first conceived the Varied Industries and Food Products Building was called the Agriculture and Horticulture Building. The name was changed to conform to exhibits inside the building. -

Balboa Park Facilities

';'fl 0 BalboaPark Cl ub a) Timken MuseumofArt ~ '------___J .__ _________ _J o,"'".__ _____ __, 8 PalisadesBuilding fDLily Pond ,------,r-----,- U.,..p_a_s ..,.t,..._---~ i3.~------ a MarieHitchcock Puppet Theatre G BotanicalBuild ing - D b RecitalHall Q) Casade l Prado \ l::..-=--=--=---:::-- c Parkand Recreation Department a Casadel Prado Patio A Q SanD iegoAutomot iveMuseum b Casadel Prado Pat io B ca 0 SanD iegoAerospace Museum c Casadel Prado Theate r • StarlightBow l G Casade Balboa 0 MunicipalGymnasium a MuseumofPhotograph icArts 0 SanD iegoHall of Champions b MuseumofSan Diego History 0 Houseof PacificRelat ionsInternational Cottages c SanDiego Mode l RailroadMuseum d BalboaArt Conservation Cente r C) UnitedNations Bui lding e Committeeof100 G Hallof Nations u f Cafein the Park SpreckelsOrgan Pavilion 4D g SanDiego Historical Society Research Archives 0 JapaneseFriendship Garden u • G) CommunityChristmas Tree G Zoro Garden ~ fI) ReubenH.Fleet Science Center CDPalm Canyon G) Plaza deBalboa and the Bea Evenson Fountain fl G) HouseofCharm a MingeiInternationa l Museum G) SanDiego Natural History Museum I b SanD iegoArt I nstitute (D RoseGarden j t::::J c:::i C) AlcazarGarden (!) DesertGarden G) MoretonBay Ag T ree •........ ••• . I G) SanDiego Museum ofMan (Ca liforniaTower) !il' . .- . WestGate (D PhotographicArts Bui lding ■ • ■ Cl) 8°I .■ m·■ .. •'---- G) CabrilloBridge G) SpanishVillage Art Center 0 ... ■ .■ :-, ■ ■ BalboaPar kCarouse l ■ ■ LawnBowling Greens G 8 Cl) I f) SeftonPlaza G MiniatureRail road aa a Founders'Plaza Cl)San Diego Zoo Entrance b KateSessions Statue G) War MemorialBuil ding fl) MarstonPoint ~ CentroCu lturalde la Raza 6) FireAlarm Building mWorld Beat Cultura l Center t) BalboaClub e BalboaPark Activ ity Center fl) RedwoodBrid geCl ub 6) Veteran'sMuseum and Memo rial Center G MarstonHouse and Garden e SanDiego American Indian Cultural Center andMuseum $ OldG lobeTheatre Comp lex e) SanDiego Museum ofArt 6) Administration BuildingCo urtyard a MayS. -

“All Artists Group Show”

SAN DIEGO ART INSTITUTE SINCE 1941 Museum Hours Tuesday - Saturday: 10am - 4pm Sunday - Noon - 4pm Closed Monday website: sandiego-art.org VOL. 9/10-10 SEPT/OCT 2010 MEMBERSHIP NEWS “All Artists Group Show” Cross-Pollination: 14 Contemporary Artists in Digital Media The San Diego Art Institute’s “Museum of the Pollination: Jill Rowe Living Artist” is celebrating the artistic diversity of our community with the 1st “All Artists Group Show.” SDAI members are encouraged to showcase their creative visions in this inclusive exhibition. One entry per artist member will be on display in the gallery from Oct. 1 through Nov. 14, 2010. The museum will hold a reception for the artists on Oct. 8th, 2010 from 6 to 8 pm. Admission is $3 for nonmembers. The public is welcome to attend. All visitors are invited to vote for the “People’s Choice Award” ($1 per ticket); the top 2 choices Location: New Americans Museum Gallery NTC Promenade at Liberty Station win all proceeds. 2875 Dewey Rd., Suite 103 San Diego, CA, 92106 ARTISTS: Check-in dates: September 14 - 26 – 1 piece per artist member. Exhibition Dates: Friday, Sept 3 – Sunday, 19, 2010 Any questions? Contact Kerstin Robers at 619.236.0011 Gallery Hours: Friday, Saturday, Sunday, 10 am – 4 pm. Admission is free Help SDAD Raise Public Events: The Public is invited to meet the artists $2,500 For A New Kiln! at the Opening Reception, Friday night, September 3, The kiln is a very important part of the San Diego 5 – 8 pm in conjunction with “Friday Liberty,” the monthly Art Department. -

1935 California Pacific International Exposition Excerpts from San Diego’S Balboa Park by David Marshall, AIA February 17, 2009

1935 California Pacific International Exposition Excerpts from San Diego’s Balboa Park by David Marshall, AIA February 17, 2009 ■ Summary Still feeling the effects from the Great Depression in 1933, San Diego’s civic boosters be lieved that another expo sition in Balboa Park would help the economy and promote the city as a business and tourist destination. The 1935 California Pacific International Exposition, also known as America’s Exposition, was born. The new buildings were paid for in part by the first WPA funds allocated to an American city. Balboa Park was re-configured by San Diego architect Richard S. Requa who also oversaw the design and construction of many new buildings. The second exposition left behind a legacy of colorful stories with its odd and controversial exhibits and sideshow entertainment. America’s Exposition also provided visitors with early glimpses of a walking silver robo t and a strange electrical device known as a “television.” Only two years after it was first conceived, the 1935 California Pacific International Exposition opened on May 29, 1935. Like the first exposition, the 1935 fair was so successful it was extended for a second year. Opening ceremonies for the second season began when President Franklin D. Roosevelt pressed a gold t elegraph ke y in the White House to turn on the exposition’s lights. When the final numbers were tallied, the 1935-1936 event counted 6.7 million visitors – almost double the total of the 1915-1916 exposition. ■ Buildings Constructed for the 1935 Exposition House of Hospitality Courtyard. For this popular patio, architect Richard Requa literally carved o ut the center of the hangar-like 1915 Foreign Arts Building and opened it to the sky. -

The Art Traveler Guide: a Portrait of Balboa Park Copyright ©2016 Save Our Heritage Organisation Edited by Alana Coons.Text by Ann Jarmusch

THE ART TRAVELER GUIDE A PORTRAIT OF BALBOA PARK 1 THE ART TRAVELER GUIDE A PORTRAIT OF BALBOA PARK ON THE COVER: “Mr. Goodhue’s Dream” (detail of Cabrillo Bridge and the California State Building) by RD Riccoboni®, a.k.a. the Art Traveler. He created all the paintings reproduced in this guide in acrylic on canvas or paper, working in Balboa Park and his San Diego studio (2006-2014). Paintings from Beacon Artworks Collection, ©RD Riccoboni. www.rdriccoboni.com MR. GOODHUE’S DREAM Acrylic on canvas, 2012 | 16 x 20 inches The Art Traveler Guide: A Portrait of Balboa Park Copyright ©2016 Save Our Heritage Organisation Edited by Alana Coons.Text by Ann Jarmusch. All rights reserved. No part of this book, either text or image may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior written permission of the publisher. Published by Our Heritage Press, 2476 San Diego Avenue, San Diego, CA 92110 ISBN-13 978-0-9800950-5-0 ISBN-10 0-9800950-5-0 THE ART TRAVELER GUIDE A PORTRAIT OF BALBOA PARK Paintings by RD Riccoboni Forward✥ by ✥ Bruce ✥ Coons Executive Director, Save Our Heritage Organisation Alana Coons, Editor Ann Jarmusch, Writer Martina Schimitschek, Designer Will Chandler and Michael Kelly, Editorial Consultants Second Edition An Our Heritage Press publication to commemorate the Centennial of the 1915 Panama-California Exposition, and to promote the preservation and celebration of historic Balboa Park in the heart of San Diego. Table of Contents Forward by Bruce Coons, Executive Director, Save Our Heritage Organisation ........ -

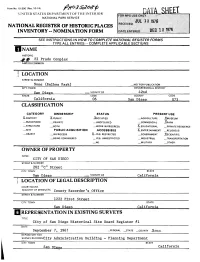

National Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMEl^OE THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Balboa Park AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET& NUMBER California Quadrangle 41 _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE California 06 San Diego 073 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE Y Y •/T") I STRICT A. p| ] pi j p .^OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE ^MUSEUM —BUtLDING(S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL J^PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS X_EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE X-ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —^YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED _YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO _MILITARY —OTHER: |OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME ________City of San _Diegp_ STREET & NUMBER City Hall, 202 C_Street____ CITY. TOWN STATE San DiegQ__________—— VICINITY OF California LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC. Qffice STREETS NUMBER 1222 First Street CITY, TOWN STATE San Diecro i •FoTni a [1 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE City of San Diego Site Board Register #1 DATE 1967 — FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY J^LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS ci Administration Building- -Planning Department CITY, TOWN STATE San Diego California DESCRIPTION W CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X_ORIGINAL SITE XGOOD _RUINS X.ALTERED _MOVED DATE_____ —FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE A brief description of the grounds at Balboa Park should begin with Bertram Goodhue's plan: "The entrance was approached across a long bridge across a canyon up to what appears to be a fortified European town—the California and Fine Arts building domi nate the view. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form Name Classification Owner of Property Location of Legal Descri

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR SHEET NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC El Prado Complex AND/OR COMMON STREET& NUMBER None CBalboa Park) _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT San Diego __ VICINITY OF 42nd STATE CODE COUNTY CODE California 06 San Diego 073 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE X_D I STRICT X-PUBLIC —^OCCUPIED _AGRICULTURE -XMUSEUM _BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL J^PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS X_EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE _SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE X-ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS X-YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT -XSCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED __YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME CITY OF SAN DIEGO STREET & NUMBER 202 "C" Street CITY, TOWN STATE San Diego VICINITY OF California LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEps.ETc. County Recorder * s Office STREET& NUMBER 1222 First Street CITY, TOWN STATE San Diego California REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE City of San Diego Historical Site Board Register #1 DATE September 7, 1967 -FEDERAL —STATE _COUNTY J$LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY REcoRosCity Administration Building - Planning Department CITY, TOWN STATE San Dj.ego California DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED ^UNALTERED -

Every Day Is Earth Day in Balboa Park Coloring Book Welcome to Balboa Park in Sunny San Diego, California

Every Day is Earth Day in Balboa Park Coloring Book Welcome to Balboa Park in sunny San Diego, California. Join our feathered friends, Muir and Carson, on a tour of some of the Park’s eco-friendly features. You will see how every day is Earth Day in Balboa Park! Muir is named after John Muir, a world-famous naturalist and ecologist. He founded the Sierra Club in 1892 to protect wilderness areas. Now the Sierra Club helps protect 250 million acres of wilderness areas. Carson is named after Rachel Louise Carson. She is famous for writing Silent Spring, a book about the dangers of polluting our air and water. Let’s get going! Thank you to our partner This program is funded by California utility customers and administered by San Diego Gas & Electric® (SDG&E®) under the auspices Illustrations by Cristina Byvik. of the California Public Utilities Commission. Go on a Balboa Park Sustainability Scavenger Hunt. Be sure to write down what you find! 1. Solar energy helps power 7. A public bus can take the Park, list at least one you to the Balboa Park place in the Park that Carousel! What number bus collects energy from the is it? sun to produce electricity. 8. There are 10 green 2. Recycling is easy. Can you buildings, also known as spot the recycle bins and LEED certified buildings in list what items you can the Park. Can you find and recycle? name one? Hint: You might find one in the coloring 3. List 3 desert plants found in pages. -

Speakers for the Opening Banquet at the Panama-California Exposition Held at the Cafe Cristobal, January 1, 1915

Speakers for the opening banquet at the Panama-California Exposition held at the Cafe Cristobal, January 1, 1915. San Diego Invites the World: The 1915 Exposition A Pictorial Essay Iris Engstrand and Matthew Schiff The first substantial groups of people traveled to California from the East Coast during the Gold Rush in 1848-49. They soon found that trains were confined to east of the Mississippi and slow-moving ships carried passengers and cargo around Cape Horn. The first railroad to cross overland and connect the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans was opened in 1855 across the Isthmus of Panama, then a part of Colombia. With the completion of the first U.S. transcontinental railroad in 1869 followed by the Santa Fe railroad in 1885, thousands of people were able to travel to California more easily, leading to a real estate boom in the 1880s. San Diego planned a city park of 1,400 acres on a central mesa. Unfortunately for San Diego, the Panic of 1893 led to a quick decline in population and properties were left vacant. With a gradual economic recovery during the early 1900s, San Diego evolved into a small city with big ambitions. Residents believed their port and city could become an important base for the US Navy, especially after the visit of Theodore Roosevelt’s Great White Fleet in 1908. An initial attempt by France to build a sea-level canal across Panama in the 1880s failed, but only after considerable excavation was carried out. This effort was useful to the United States, which completed the present Panama Canal in Iris Engstrand is Professor of History at the University of San Diego and co-editor of The Journal of San Diego History. -

California Pacific International Exposition 1935

Be sure to come to the JUNKET EXHIBIT Booths 35 and 36— Palace of Foods and Beverages * • San Diego Exposition See how easy it is to make CREAMIER ICE CREA in your electric refrigerator or hand freezer with JUNKET MIX Get a FREE ice cream cone full of smooth, creamy Junket ice cream. No trouble at all to make. No cooking. No warming. No stirring while freez ing. And perfectly delicious ice cream is the result, every single time. So much easier to digest than all other ice creams, too, because Junket ice cream contains the Junket enzyme. Approved by Good Housekeeping In stitute. Doctors recommend it. Pure and wholesome for children . and how they love it! Dainty Junket desserts digest twice as fast In one minute Junket Powder or Junket Tablets transform milk into delicious, nourishing des serts which children love. The Junket enzyme makes Junket desserts digest approximately twice as fast as fresh milk. Make Junket with either Junket Powder or Junket Tablets. Junket Powder is sweetened and flavored: Vanilla Chocolate Lemon Orange Raspberry Caramel Junket Tablets, not sweetened or flavored. Add sugar and flavor to taste. The Junket Folks Dept. 5, Little Falls, N. Y. JUNKET MIX TOT K*« U. 3 P,t. Off. •W« • ^^ Vanilla making Chocolate orMople Ice Cream A cone foil of Junket ice cream given FREE »« «-.L . v T-n rKtt to each person at exhibit TRANSPORTATION At the Exposition, or on the road/ TOR COMPUTE INfOHM ATI ON Coming to the Exposition Within the Grounds Because of the convenient location of Balboa Inside the Exposition Grounds will be oper Park it is quickly accessible via Street Car or ated the Special Exposition Buses.