331 the Discovery, Exploration and Early

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MT PERRY Community Development Strategy 2018 to 2020

MT PERRY Community Development Strategy 2018 to 2020 FebruaryMt Perry| 2018 Community Development Strategy 2018-2020 1 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This document has been developed by the Mount Perry Community GAME CHANGING RECOMMENDATIONS Development Board (MPCDB) with input from the community to provide a framework and direction for the economic and community development 1. Work with the Mt Rawden Mine to develop a Mine Tour experience priorities for the next three years. available to visitors and test the concept through Bundaberg North Burnett Tourism Strategic priorities have been developed to align with the MPCDB and community’s development goals, which include increasing quality of life, 2. Redevelopment of the park and the Main Street to become an increasing Mt Perry’s population, the diversification of business and attraction with the assistance of a volunteer workforce to create an employment opportunities and capturing more visitor spend locally. attractive entry to town 3. Lobby for sealing of the Mingo Crossing Road through an economic This has been framed within the context of the current Mt Perry Business Case demographic and economic situation, and highlights key approaches such as: 4. Revitalisation of the Mt Perry summit walk with weeding, signage • Event development and marketing and ongoing maintenance. • Product and experience development 5. Establishment of an Events Coordination Position for a minimum of • Industry support 3 years as a driver of publicity, advocacy and creating further linkages • Visitor services • Community places 6. Undertake an Options Study of the ideal location for a pool either at the School, Caravan Park and Main Street including cost of It is the intention that the actions within these strategic priorities will development and operating models revitalise Mt Perry both socially and economically, providing a secure 7. -

Johnathon Davis Thesis

Durithunga – Growing, nurturing, challenging and supporting urban Indigenous leadership in education John Davis-Warra Bachelor of Arts (Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Studies & English) Post Graduate Diploma of Education Supervisors: Associate Professor Beryl Exley Associate Professor Karen Dooley Emeritus Professor Alan Luke Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Education Queensland University of Technology 2017 Keywords Durithunga, education, Indigenous, leadership. Durithunga – Growing, nurturing, challenging and supporting urban Indigenous leadership in education i Language Weaves As highlighted in the following thesis, there are a number of key words and phrases that are typographically different from the rest of the thesis writing. Shifts in font and style are used to accent Indigenous world view and give clear signification to the higher order thought and conceptual processing of words and their deeper meaning within the context of this thesis (Martin, 2008). For ease of transition into this thesis, I have created the “Language Weaves” list of key words and phrases that flow through the following chapters. The list below has been woven in Migloo alphabetical order. The challenge, as I explore in detail in Chapter 5 of this thesis, is for next generations of Indigenous Australian writers to relay textual information in the languages of our people from our unique tumba tjinas. Dissecting my language usage in this way and creating a Language Weaves list has been very challenging, but is part of sharing the unique messages of this Indigenous Education field research to a broader, non- Indigenous and international audience. The following weaves list consists of words taken directly from the thesis. -

Celebrating Our High Achievers

www.health.qld.gov.au/widebay /widebayhealth [email protected] DEC 18, 2019 Celebrating our high achievers The achievements of health staff and volunteers across Wide Bay were recognised at WBHHS’s second annual Excellence Awards on December 4. The awards, which were held at The Waves sports club in Bundaberg, focused on how the actions of staff and volunteers have led to improvements in care for local patients. Seven awards in total were presented at the dinner, in categories of Leadership, Collaboration and Teamwork, Innovation, Volunteer, Early Achievers, Unsung Heroes – and the major trophy, the Care Comes First Winners and finalists at the WBHHS Exellence Awards, held at The Waves sports club in Bundaberg. Excellence Award. Queensland’s Chief Health Officer, “As an organisation, we can’t achieve what’s being achieved by other WBHHS teams Dr Jeannette Young, also attended the anything without our staff, so the evening and individuals, and to be encouraged and evening and presented several awards to was a great opportunity for us not only to inspired by their colleagues,” Debbie said. finalists and winners, alongside Board Chair congratulate our finalists and winners on Peta Jamieson and Acting Chief Executive their efforts, but also to say thank you for “There was a great deal of diversity in the Debbie Carroll. doing a really important job that helps to finalists and winners – in the geographic improve the lives of our community.” areas people were from, in the services they provide and the projects they’ve been These awards are an important Debbie said the awards were an excellent working on. -

Gayndah Jewellers

The Issue: 03/13 Wednesday, 10 April 2013 $1.20 Gayndah GazetteGazette Locally Owned and Produced Phone: 4161 1477 Fax: 4161 1098 Email: [email protected] 63 Capper Street (PO Box 215), Gayndah Qld 4625 Brooke Geary Takes Out 2013 Miss Showgirl Title The Gayndah Town Hall was the venue being actively involved in promoting an honour to win, but I entered for the n for the Gayndah Show Society Miss events in our town and being advocates amazing opportunity this will give me. Showgirl presentations last Saturday night, for our community especially in light of The interview and process will provide April 6. A crowd of around 100 people the floods and devastation we experienced an experience valuable to my future. I have saw 18 year old Brooke Geary announced earlier this year.” seen small shows struggle to survive over as Miss Showgirl 2013 with Juanita Elllis The entrants were judged during a the past few years and believe they play an as Runner up from four entrants. morning tea which was hosted by Central extremely important role in communities. Miss Showgirl co-ordinators, Stacey and Upper Burnett District Home for the The Showgirl competition provides an Duncan and Amy Hampson said “We Aged. opportunity to raise the profile of local commend these girls on their decision to Brooke, a full time university student shows and is one way that allows me to enter the Gayndah Miss Showgirl was asked why she would like to win show my support. If I’m offered the competition. It is great to see young people Miss Showgirl and she said “It would be opportunity to be Miss Showgirl, I will endeavour to represent my district to the best of my ability and showcase its people, agriculture and show.” Brooke will represent Gayndah at the regional Miss Showgirl judging which will take place in Mundubbera. -

Surface Water Ambient Network (Water Quality) 2020-21

Surface Water Ambient Network (Water Quality) 2020-21 July 2020 This publication has been compiled by Natural Resources Divisional Support, Department of Natural Resources, Mines and Energy. © State of Queensland, 2020 The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) licence. Under this licence you are free, without having to seek our permission, to use this publication in accordance with the licence terms. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the State of Queensland as the source of the publication. Note: Some content in this publication may have different licence terms as indicated. For more information on this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The information contained herein is subject to change without notice. The Queensland Government shall not be liable for technical or other errors or omissions contained herein. The reader/user accepts all risks and responsibility for losses, damages, costs and other consequences resulting directly or indirectly from using this information. Summary This document lists the stream gauging stations which make up the Department of Natural Resources, Mines and Energy (DNRME) surface water quality monitoring network. Data collected under this network are published on DNRME’s Water Monitoring Information Data Portal. The water quality data collected includes both logged time-series and manual water samples taken for later laboratory analysis. Other data types are also collected at stream gauging stations, including rainfall and stream height. Further information is available on the Water Monitoring Information Data Portal under each station listing. -

FLOOD WARNING SYSTEM for the BURNETT RIVER

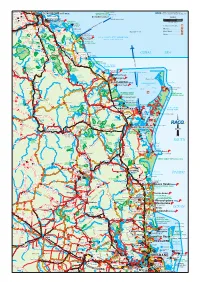

Bureau Home > Australia > Queensland > Rainfall & River Conditions > River Brochures > Burnett FLOOD WARNING SYSTEM for the BURNETT RIVER This brochure describes the flood warning system operated by the Australian Government, Bureau of Meteorology for the Burnett River. It includes reference information which will be useful for understanding Flood Warnings and River Height Bulletins issued by the Bureau's Flood Warning Centre during periods of high rainfall and flooding. Contained in this document is information about: (Last updated September 2019) Flood Risk Previous Flooding Flood Forecasting Local Information Flood Warnings and Bulletins Interpreting Flood Warnings and River Height Bulletins Flood Classifications Other Links Burnett River at Mundubbera Flood Risk The Burnett River is located on the southern Queensland coast with the mouth of the river sited just north of the City of Bundaberg. The total area of the catchment is about 33,000 square kilometres. The Burnett River rises in the Dawes Range, just north of Monto and flows south through Eidsvold and Mundubbera. Along the way it is joined by the Nogo and Auburn Rivers which drain large areas in the west of the catchment. Just before Mundubbera, the main river is joined by the Boyne River draining areas from the south and then begins its northeasterly journey to the coast. Between Gayndah and Mt Lawless, the Barker-Barambah Creeks system joins the Burnett River. Major flooding in the Burnett River is relatively infrequent. However, under favourable meteorological conditions such as a tropical low pressure system, heavy rainfalls can occur throughout the catchment which can result in significant river level rises and floods. -

State of the Park 2016

Magazine of National Parks Association of Queensland state of the park 2016 why advocacy matters bunya mountains national park warrie circuit walk lamington spiny crayfish the national park experience Issue 7 February-March 2016 1 Welcome to Contents the February/ Welcome to Protected 2 March edition of State of the park 2016 3 Protected Why advocacy matters 6 Bunya Mountains National Park 8 Michelle Prior, NPAQ President Warrie Circuit walk, Springbrook 10 As this edition of Protected goes to Lamington spiny crayfish 12 press, NPAQ is eagerly awaiting the outcome of the Nature Conservation The National Park Experience 13 and Other Legislation Amendment Bill What’s On 14 2015, which if passed, will reinstate Letters to the Editor 15 the nature as the sole goal of the NC Act (which governs the creation and management of national parks Council President Michelle Prior in Queensland), and undo some Vice Presidents Tony O’Brien retrograde amendments made during Athol Lester the Newman term of government. Hon Secretary Debra Marwedel Asst Hon Secret Yvonne Parsons Another important issue currently Hon Treasurer Graham Riddell in the pipeline is the opportunity to Councillors Julie Hainsworth phase out sand mining on North Peter Ogilvie Stradbroke Island by 2019, supported Richard Proudfoot by an economic transition package. Des Whybird The Bill which proposes this end Mike Wilke date also serves to respect the rights Staff of the native title holders of North Conservation Principal: Stradbroke Island. The government Kirsty Leckie has a responsibility to protect and Business Development Officer: preserve what remains of the island’s Anna Tran remarkable natural environment and Project & Office Administrator: stem the tide of irreversible damage. -

AUSTRALIAN BIODIVERSITY RECORD ______2007 (No 2) ISSN 1325-2992 March, 2007 ______

AUSTRALIAN BIODIVERSITY RECORD ______________________________________________________________ 2007 (No 2) ISSN 1325-2992 March, 2007 ______________________________________________________________ Some Taxonomic and Nomenclatural Considerations on the Class Reptilia in Australia. Some Comments on the Elseya dentata (Gray, 1863) complex with Redescriptions of the Johnstone River Snapping Turtle, Elseya stirlingi Wells and Wellington, 1985 and the Alligator Rivers Snapping Turtle, Elseya jukesi Wells 2002. by Richard W. Wells P.O. Box 826, Lismore, New South Wales Australia, 2480 Introduction As a prelude to further work on the Chelidae of Australia, the following considerations relate to the Elseya dentata species complex. See also Wells and Wellington (1984, 1985) and Wells (2002 a, b; 2007 a, b.). Elseya Gray, 1867 1867 Elseya Gray, Ann. Mag. Natur. Hist., (3) 20: 44. – Subsequently designated type species (Lindholm 1929): Elseya dentata (Gray, 1863). Note: The genus Elseya is herein considered to comprise only those species with a very wide mandibular symphysis and a distinct median alveolar ridge on the upper jaw. All members of the latisternum complex lack a distinct median alveolar ridge on the upper jaw and so are removed from the genus Elseya (see Wells, 2007b). This now restricts the genus to the following Australian species: Elseya albagula Thomson, Georges and Limpus, 2006 2006 Elseya albagula Thomson, Georges and Limpus, Chelon. Conserv. Biol., 5: 75; figs 1-2, 4 (top), 5a,6a, 7. – Type locality: Ned Churchwood Weir (25°03'S 152°05'E), Burnett River, Queensland, Australia. Elseya dentata (Gray, 1863) 1863 Chelymys dentata Gray, Ann. Mag. Natur. Hist., (3) 12: 98. – Type locality: Beagle’s Valley, upper Victoria River, Northern Territory. -

MONTO Agricultural Strategy a Regional Approach to Growing Australia’S Economy and Rural Communities

August 2019 MONTO Agricultural Strategy A regional approach to growing Australia’s economy and rural communities 1 2 Monto Agricultural Strategy Strategy Officer: Naomi Purcell Compiled by: Misty Neilson-Green Contributors: Katie Muller, Hannah Vicary, Melinda Clarke, Marisa Young and Kirstie Roffey Burnett Catchment Care Association Inc., 2019 Front Cover Photo: Dieta Salisbury Photo Contributors: BCCA, Dieta Salisbury, Katie Muller, Melinda Clarke, Melissa Brown, Misty Green, Naomi Purcell, Pixabay.com 3 Acknowledgements We wish to acknowledge the traditional owners of the lands and waters that support our region and recognise their continued spiritual and cultural connection to land, water and community. We pay our respects to Elders past, present and emerging. The Monto Agricultural Strategy was developed by Burnett Catchment Care Association in partnership with the North Burnett Regional Council (NBRC), Burnett Inland Economic Development Organisation (BIEDO), Monto Growers Group and FARMstuff Monto. This project was made possible thanks to the Australian Government’s ‘Building Better Regions Fund – Community Investment Stream’. Monto Growers Group 4 Contents Message from the Mayor ........................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 About the Monto Agricultural Strategy ...................................................................................................................................................................... -

(In Ballot Paper Order) 2008 North Burnett Regional Council

2008 North Burnett Regional Council - Councillor Election held on 15/03/2008 Candidate Details (in Ballot Paper order) Division 1 Candidate: CROWTHER, Andrew Contact Person: Andrew Norman Crowther Ph (B): (07) 4166 3373 21 KELVIN Street MONTO QLD 4630 Candidate: LOBEGEIER, Paul Contact Person: Paul William Lobegeier Ph (B): (07) 4167 2257 986 KAPALDO Road Ph (AH): (07) 4167 2257 KAPALDO QLD 4630 Mob: 0427 678 972 Fax: (07) 4167 2089 Division 2 Candidate: FRANCIS, Paul Contact Person: Paul Wilson Francis Ph (B): (07) 4167 8134 CANIA HOMESTEAD Ph (AH): (07) 4167 8134 570 CANIA Road MOONFORD QLD 4630 Fax: (41) 6781 34 Email: [email protected] Candidate: BOOTHBY, Margaret Contact Person: Margaret Alison Boothby Ph (B): (07) 4165 0852 CHESS PARK Ph (AH): (07) 4165 0852 16555 REDBANK Road EIDSVOLD WEST QLD 4627 Email: [email protected] Division 3 Candidate: WHELAN, Faye Contact Person: Faye Olive Whelan Ph (B): (07) 4165 4311 6 RYAN Avenue Ph (AH): (07) 4165 4363 MUNDUBBERA QLD 4626 Mob: 0428 654 676 Fax: (07) 4165 4311 Email: [email protected] Candidate: DOESSEL, Loris Contact Person: LORIS JEAN DOESSEL Ph (B): (07) 4165 3261 PO Box 46 Ph (AH): (07) 4165 3261 MUNDUBBERA QLD 4626 Mob: 0429 654 012 Fax: (07) 4165 3261 Email: [email protected] Candidate: SINNAMON, Phil Contact Person: Phillip John Sinnamon Ph (B): (04) 2765 4623 PO Box 94 Mob: 0427 654 623 MUNDUBBERA QLD 4626 Fax: (07) 4165 3190 Email: [email protected] Tuesday February 17 2015 11:05 AM Page 1 of 3 2008 North Burnett Regional Council - -

Open to Full Area Map (4MB)

Hoskyn Islands Mount Larcom 19 16 All Rights Reserved RACQ May 2010 BRUCE 2GLADSTONE CAPRICORNIA CAYS For more detail refer to RACQ District Map Series Machine Creek Yarwun NAT PK (scientific) Fairfax Is (Locality) Gatcombe Head East R SCALE End BUNKER GROUP Bracewell 12 17 10 0 10 20 27 19 19 Boyne Island Lady Musgrave Island R Tannum Sands Cedarvale 7 EURIMBULA KILOMETRES (Locality) Wild Cattle Island 16 Benaraby RODDS BAY NATIONAL PARK land 4 2 A1 6 7 Hummock Hill Bustard Head Island Lighthouse sgrave Is Heritage, Historic Site . HWY Mu Calliope R Turkey Beach Museum . 15 16 Middle Island N Taragoola Boat to Lady Awoonga 64 Bustard Bay Lady Elliot Island Whale Watch . DAWSO Dam 17 Barmundu Iveragh Round Hill Head HWY Winery . Seventeen Seventy DAD DAN 6 GREAT BARRIER REEF MARINE PARK NAT PARK CASTLE 10 EURIMBULA Agnes Water Boynedale TOWER Bororen NAT PKOyster Rocky Point (MACKAY / CARRICORN SECTION) M NAT PK A WIETALABA N 18 DEEPWATER 28 Y 4WD NAT PARK Boyne PEA 63 NATIONAL PARK Wietalaba 13 KS Miriam Vale RA 13 Creek Nagoorin BULBURIN 6 KROOMBITCALLIOPE NAT PK 20 6 River 16 TOPS Ubobo A1 Fligh 31 (Locality) NAT PARK Oyster Creek MT COLOSSEUM CORAL SEA 6 Petrol (Locality) ts Littlemore NAT (Locality) No petrol between t Baffle o L RA PK Rules Beach 8 here and Gin Gin 26 Creek ad DAWES 20 Lowmead y NATIONAL Many Peaks (Locality) Elliot PARK LITTABELLA Lake BULBURIN 16 NATIONAL PARK Isla 26 NATIONAL Rosedale Cania 15 GREAT SANDY nd PARK BRUCE Cania Dam MARINE PARK CANIA GORGE Kolan WARRO NATIONAL BURNETT Kalpowar 99 NATIONAL Sandy Cape -

Gayndah-Baptisms-15Feb2021.Pdf

Diocesan Records Archives Gayndah Baptisms 1860-1877 ; 1891-1894 ID Surname Christian Names Date of Birth Date of Baptism Father's Surname Father's Christian Name Father's Profession Mother's Maiden Name Mother's Christian Abode Town or Parish Celebrant or Notes and Links Names Priest 1 Speering James Julius 1/05/1858 4/11/1860 Speering James Tailor Angelina Gayndah Gayndah D.C. Mackenzie Andrews 2 Speering Edwin Ernest 5/05/1860 4/11/1860 Speering James Tailor Augelina Gayndah Gayndah D.C. Mackenzie Charles 3 Rien Anna Margarita 30/11/1856 9/11/1860 Rien Conrad Labourer Elizabeth Boorinia Gayndah Bishop E.W. Tufnell 4 Rien Catherine 16/04/1859 9/11/1860 Rien Conrad Labourer Elizabeth Boorinia Gayndah Bishop E.W. Tufnell 5 Walker Gustav 19/11/1856 20/11/1860 Walker John George Shepherd Frederica Coranga Gayndah D.C. Mackenzie 6 Walker William 22/05/1858 20/11/1860 Walker John George Shepherd Frederica Coranga Gayndah D.C. Mackenzie 7 Tobler Nicholas 18/06/1860 28/11/1860 Tobler Frederick Labourer (German) Agnes Hawkwood Gayndah D.C. Mackenzie 8 Cheery William 12/11/1857 2/12/1860 Cherry John Overseer Sarah Boondooma Gayndah D.C. Mackenzie 9 Cherry Eliza 4/03/1860 2/12/1860 Cherry John Overseer Sarah (entered as Boondooma Gayndah D.C. Mackenzie 'George') 10 Weldon Rosa 20/09/1860 9/12/1860 Weldon Henry Alexander Groom Elizabeth Jane Tabinga Gayndah D.C. Mackenzie 11 Mason Margaret Jane 19/06/1860 11/12/1860 Mason Charles Superintendent Margaret Barambah Gayndah D.C.