Vision Loss in Older Persons ALLEN L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Approved and Unapproved Abbreviations and Symbols For

Facility: Illinois College of Optometry and Illinois Eye Institute Policy: Approved And Unapproved Abbreviations and Symbols for Medical Records Manual: Information Management Effective: January 1999 Revised: March 2009 (M.Butz) Review Dates: March 2003 (V.Conrad) March 2008 (M.Butz) APPROVED AND UNAPPROVED ABBREVIATIONS AND SYMBOLS FOR MEDICAL RECORDS PURPOSE: To establish a database of acceptable ocular and medical abbreviations for patient medical records. To list the abbreviations that are NOT approved for use in patient medical records. POLICY: Following is the list of abbreviations that are NOT approved – never to be used – for use in patient medical records, all orders, and all medication-related documentation that is either hand-written (including free-text computer entry) or pre-printed: DO NOT USE POTENTIAL PROBLEM USE INSTEAD U (unit) Mistaken for “0” (zero), the Write “unit” number “4”, or “cc” IU (international unit) Mistaken for “IV” (intravenous) Write “international unit” or the number 10 (ten). Q.D., QD, q.d., qd (daily) Mistaken for each other Write “daily” Q.O.D., QOD, q.o.d., qod Period after the Q mistaken for Write (“every other day”) (every other day) “I” and the “O” mistaken for “I” Trailing zero (X.0 mg) ** Decimal point is missed. Write X mg Lack of leading zero (.X mg) Decimal point is missed. Write 0.X mg MS Can mean morphine sulfate or Write “morphine sulfate” or magnesium sulfate “magnesium sulfate” MSO4 and MgSO4 Confused for one another Write “morphine sulfate” or “magnesium sulfate” ** Exception: A trailing zero may be used only where required to demonstrate the level of precision of the value being reported, such as for laboratory results, imaging studies that report size of lesions, or catheter/tube sizes. -

Bilateral Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment in an Asymptomatic Patient Julie L

Bilateral Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment in an Asymptomatic Patient Julie L. Marsh, OD; Heather R. Miller, OD; Renae E. Welke, OD; Andrew Gurwood, OD Retinal detachments occur in approximately 2.8% of patients who have lattice degeneration with holes.1,2 We present a case of bilateral asymptomatic rhegmatogenous retinal detachments successfully repaired with a silicone exoplant encircling buckle, cryotherapy, and barrier laser. I. Case history A 44-year-old African-American male presented with no visual or ocular complaints for an ocular examination to update their spectacle and contact lens prescriptions. The patient denied history of trauma, flashes, floaters, or decreased vision. The patient’s ocular and medical histories were unremarkable. II. Pertinent findings Best-corrected visual acuities measured 20/20 OD and 20/70 OS. Pupils were equal, round, and responsive to light with an afferent pupillary defect noted OS. Brightness and red cap testing were negative. Versions were smooth and full in all positions of gaze. Confrontation visual fields were full to finger counting OD. Confrontation visual field testing OS revealed an 8- degree superior nasal defect, which was confirmed with an Amsler grid. Refractive error was measured with negligible changes at -5.50 – 2.50 X 180 OD and - 7.50 – 3.00 X 180 OS. Slit lamp examination was unremarkable in both eyes. Intraocular pressures measured 14 mmHg OU by Goldmann applanation tonometry. Dilated fundus examination of both eyes revealed lattice degeneration with holes in all quadrants. The left eye demonstrated an inferior temporal retinal tear infiltrated with subretinal fluid creating a rhegmatogenous retinal detachment, extending into the macula. -

Root Eye Dictionary a "Layman's Explanation" of the Eye and Common Eye Problems

Welcome! This is the free PDF version of this book. Feel free to share and e-mail it to your friends. If you find this book useful, please support this project by buying the printed version at Amazon.com. Here is the link: http://www.rooteyedictionary.com/printversion Timothy Root, M.D. Root Eye Dictionary A "Layman's Explanation" of the eye and common eye problems Written and Illustrated by Timothy Root, M.D. www.RootEyeDictionary.com 1 Contents: Introduction The Dictionary, A-Z Extra Stuff - Abbreviations - Other Books by Dr. Root 2 Intro 3 INTRODUCTION Greetings and welcome to the Root Eye Dictionary. Inside these pages you will find an alphabetical listing of common eye diseases and visual problems I treat on a day-to-day basis. Ophthalmology is a field riddled with confusing concepts and nomenclature, so I figured a layman's dictionary might help you "decode" the medical jargon. Hopefully, this explanatory approach helps remove some of the mystery behind eye disease. With this book, you should be able to: 1. Look up any eye "diagnosis" you or your family has been given 2. Know why you are getting eye "tests" 3. Look up the ingredients of your eye drops. As you read any particular topic, you will see that some words are underlined. An underlined word means that I've written another entry for that particular topic. You can flip to that section if you'd like further explanation, though I've attempted to make each entry understandable on its own merit. I'm hoping this approach allows you to learn more about the eye without getting bogged down with minutia .. -

Myopic Macular Degeneration Myopic Macular Degeneration Can Occur in People Who Are Severely Short-Sighted Due to Extreme Elongation of the Eyeball

Myopic Macular Degeneration Myopic macular degeneration can occur in people who are severely short-sighted due to extreme elongation of the eyeball. The stretching of the retina can result in tears in the macula and bleeding beneath the retina. How the eye works Light passes through the cornea at the front of your eye, and is focused by the lens onto your retina. The retina is a delicate tissue that lines the inside of your eye. The retina converts the light into electrical signals that travel along the optic nerve to your brain. The brain interprets these signals to “see” the world around you. Light from the object you are looking at directly is focused onto a tiny area of the retina called the macula at the back of the eye. The macula is about 4mm across and is responsible for detailed central vision and most colour vision. It provides the vision you need to read, recognise faces, drive a car, see colours clearly, and any other activity that requires detailed, fine vision. The rest of the retina gives you side vision (peripheral vision). What is myopia? Myopia, often known as “being short-sighted”, causes vision to be blurry in the distance but clearer when looking at things up close. It is a very common condition of the eyes and, for most people, it can easily be dealt with using contact lenses or glasses which will make vision clear and crisp. Most people have myopia because their eyeball has grown too long or their cornea (the clear window at the front of the eye) is more steeply curved than usual. -

A Comparative Study of Chart 1 and Chart 7 of Amsler Grid in Early Detection of Symptomatic Diabetic Macular Edema

Available online at www.iponlinejournal.com Journal homepage: www.innovativepublication.com/journal/ijooo Original Research Article A comparative study of chart 1 and chart 7 of amsler grid in early detection of symptomatic diabetic macular edema Nilesh Shrimali1, Minhaz Karkhanawala2, Somesh Aggarwal3*, Uma Gajiwala4, Pratik katariya5 1,4,5Resident, 2Senior Resident, 3Professor and Head of Retina Unit, M and J Western Regional Intitute of Ophthalmology Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India Abstract Objective: The aim of this study is to compare the sensitivities of chart 1 and chart 7 of the Amsler grid in early detection of metamorphopsia suggestive of diabetic macular edema. Design: It was a randomized, prospective, analytical study. Eighty patients were divided into two equal groups- A and B. Group A patients were given Amsler chart 1 and group B patients given Amsler chart 7.Regular 3 monthly follow up was done for 2 years with Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) to detect DME on every follow up. Setting: Retina Unit, M And J Western Regional Institute Of Ophthalmology, Civil Hospital, Asarwa, Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India. Subjects: 80 eyes of 80 patients were enrolled, equally divided into 2 groups of 40 patients each. Intervention: No intervention was done for purpose of study. DME was treated as per clinical guidelines. Main outcome and Measures: Sensitivity and Specificity of both Amsler chart were calculated and compared using statistical analysis. Results: The sensitivity of Chart 1 of Amsler grid in detecting metamorphopsia was 56.25 percent, whereas the sensitivity of Chart 7 of Amsler grid was 76.47 percent. The difference was statistically significant (P< 0.05). -

Threshold Amsler Grid As a Screening Tool for Asymptomatic Patients On

569 EXTENDED REPORT Br J Ophthalmol: first published as 10.1136/bjo.2004.050120 on 15 April 2005. Downloaded from Threshold Amsler grid as a screening tool for asymptomatic patients on hydroxychloroquine therapy A Almony, S Garg, R K Peters, R Mamet, J Tsong, B Shibuya, R Kitridou, A A Sadun ............................................................................................................................... Br J Ophthalmol 2005;89:569–574. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2004.050120 See end of article for Background/aims: Patients taking hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) are at risk of developing classic bull’s eye authors’ affiliations maculopathy. Currently, the standard Amsler grid (AG) is one of the most useful methods to identify such ....................... lesions. However, AG is a suprathreshold target and may not detect relative central scotomas. The aim of Correspondence to: this study was to determine if the threshold Amsler grid (TAG) test, which varies light transmission through Alfredo A Sadun, two cross polarising filters, allows increased detection of scotomas caused by HCQ toxicity. MD, PhD, Department of Ophthalmology, Keck Methods: 56 rheumatological patients taking HCQ and 12 similar patients not taking HCQ were tested by School of Medicine, AG, red Amsler grid (RAG), and TAG. University of Southern Results: No scotomas were observed in patients never treated with HCQ. Among patients who had been California, Doheny Eye treated with HCQ, AG revealed scotomas in two of 56 (3.64%) patients; in contrast, six (10.7%) and 37 Institute, 1450 San Pablo Street, Los Angeles, CA (66.1%) scotomas were identified by RAG and TAG testing respectively. Additionally, the average area of 90033-1026, USA; each scotoma detected by all three methods expanded from 34.5 square degrees of central field loss on [email protected] AG testing to 71 square degrees on RAG and 117 on TAG. -

Clinical Findings and Management of Pathological Myopic Degeneration with Secondary Choroidal Neo-Vascular Membrane Macular Hemorrhages

Case Report JOJ Ophthal Volume 6 Issue 3 - February 2018 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Brad Thomas Cunningham DOI: 10.19080/JOJO.2018.06.555690 Clinical Findings and Management of Pathological Myopic Degeneration with Secondary Choroidal Neo-Vascular Membrane Macular Hemorrhages Brad Thomas Cunningham* New England College of Optometry, USA Submission: January 29, 2018; Published: February 21, 2018 *Corresponding author: Brad Thomas Cunningham, New England College of Optometry, USA, Email: Abstract appears to be increasing [2]. Considered a small subpopulation of myopia, pathological myopia (PM) is a disease affecting up to three percent of theMyopia, world populationor nearsightedness with a 31 affects percent over chance 40 percent of inheritability of the people [3,4]. aged Since 12-54 the typical in the courseUnited ofStates PM varies [1]. This greatly gender with non-specific visual outcomes, condition it is treatmentcritical for optionsclinicians as tothey appreciate relate to the the severity case presented. of the clinical The expected findings, prevalence the course of of myopia the disease, and PM and demands take a collaborative our attention approach and further to treatment analysis. Newoptions and before alternative pursuing treatment interventions. options must This becase evaluated. report reviews the management of a patient with PM and discusses clinical findings and Keywords: Pathological myopia; Fluorescein angiography; Choroidal neovascular membrane Case Report surgeon, who successfully completed bilateral DCR’s. The patient Patient #1, a 36-year-old Filipino female Army active duty healed completely and continues her regiment of daily patanol dentist, presented in the optometry clinic on May 15, 2012 as an urgent walk-in due to “a black spot” in her vision. -

Retinal Conditions

GENERAL INFORMATION RETINAL CONDITIONS RETINAL CONDITIONS WHAT ARE RETINAL CONDITIONS? Retinal conditions affect the light-sensitive tissue at the back of eye known as the retina. They include diseases that affect the part of the retina responsible for central vision (the macula) and the jelly-like fluid that sits in front of the retina (the vitreous). The retina acts like the ‘film’ of a camera, sending information about shapes, colours, patterns and movement via the optic nerve to the brain, where the information is processed into the final image that we see. DAMAGE TO THE RETINA CAUSES VISUAL DISTURBANCES OR LOSS OF VISION. RETINAL CONDITIONS 2 RETINAL CONDITIONS The main conditions that affect the retina are: Macular degeneration: A group of degenerative diseases of the macula that cause loss of central and fine-detail vision. Treatment to stop or slow the progression of the wet form includes eye injections and photodynamic therapy. Unfortunately, there is no approved treatment for the dry form. Diabetic retinopathy: An eye disease caused by the persistently high blood sugar levels that occur with diabetes. Depending on the stage of disease, treatment includes eye injections, retinal laser treatment and vitrectomy surgery (keyhole surgery to remove the vitreous). The most advanced stage of the disease is an ocular emergency that can cause total vision loss. Retinal vein occlusion: Vision loss that occurs when the veins in the retina are blocked and the build-up of pressure causes smaller downstream blood vessels to leak. The blockage can occur in a branch vein with vision loss restricted to part of the visual field (branch vein retinal occlusion) or a central vein with the entire visual field affected (central vein retinal occlusion). -

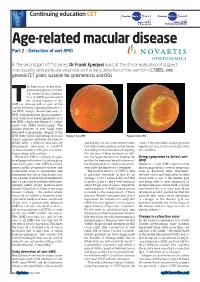

Age-Related Macular Disease Part 2 – Detection of Wet AMD

Continuing education CET Age-related macular disease Part 2 – Detection of wet AMD In the second part of this series, Dr Frank Eperjesi looks at the clinical evaluation of suspect maculopathy with particular emphasis on the early detection of the wet form. C7881, one general CET point, suitable for optometrists and DOs he first article in this three- part series (Optician, October 19) looked at the classifica- tion of AMD and described the clinical features of dry TAMD as: discrete yellow spots at the macula (drusen), hyperpigmentation of the RPE, sharply demarcated areas of RPE depigmentation (hypopigmenta- tion) with focal hyperpigmentation of the RPE a high-risk feature for subse- quent wet AMD development. The clinical features of wet AMD were described as geographic atrophy of the RPE with visible underlying choroidal Figure 1 Dry AMD Figure 2 Wet AMD vessels, pigment epithelial detachment (PED) with or without neurosensory and halt vision loss or even reverse vision onset of the inevitable and progressive detachment, subretinal or sub-RPE loss with smaller and less central lesions. significant visual loss associated with neovascularisation, fibroglial scar tissue, According to recent studies investigating the condition. haemorrhage and exudates. the outcome of these treatment modali- While dry AMD is a slowly progres- ties, the larger the lesion at baseline the Using symptoms to detect wet sive disease with vision loss taking place smaller the treatment benefit in terms of AMD over many years, wet AMD is a much the absolute level of visual acuity at two Detection of wet AMD often involves more rapidly progressive disease and years after the initiation of treatment. -

Erdafitinib) – Ocular Toxicities: Overview, Screening and Management

BALVERSA™ (erdafitinib) – Ocular Toxicities: Overview, Screening and Management January 14, 2020 (V1.1) Disclaimer: Thank you for your interest in BALVERSA™ (erdafitinib). The following information is provided because of your specific unsolicited request and is not intended as an endorsement of any usage not contained in the Product Monograph. For complete information, please refer to the BALVERSA™ Product Monograph. For additional information, please see the full scientific summary accompanying these materials.† † Please login to your JanssenMedicalInformation.ca account to view the scientific summary. Table of contents: Central Serous Retinopathy (CSR) – Definition 1 and General Treatment (Slides 4-6) Incidence of CSR and Eye Disorders with 2 Erdafitinib (Slides 7-8) CSR Screening and Management per BLC2001 Protocol and BALVERSA™ Product 3 Monograph (Slides 8-14) 4 Other Eye Disorders (Slides 15-16) 5 Summary (Slide 17) Central Serous Retinopathy (CSR)1-4 . A condition in which fluid accumulates under the retina, causing a serous (fluid-filled) detachment of the retinal epithelium and vision loss . Symptoms include blurry central vision, which often occurs in one eye . Patients with CSR can show no Fundoscopy symptoms, especially if the affected areas fall outside of the macula . Detected and quantified with optical coherence tomography (OCT) . Treatment is usually not necessary because most cases of CSR resolve without treatment after several weeks OCT or months . If retinal swelling persists for more than three or four months, or if an examination reveals early retinal degeneration, laser surgery may be helpful. 1. Francis et al., Ophthalmology. 2017 Dec;124(12):1788-1798. 2. Central serous chorioretinopathy. Retina Image Bank 2012; Image 2117. -

Recent Advances of Computerized Graphical Methods for the Detection and Progress Assessment of Visual Distortion Caused by Macular Disorders

Review Recent Advances of Computerized Graphical Methods for the Detection and Progress Assessment of Visual Distortion Caused by Macular Disorders Navid Mohaghegh, Ebrahim Ghafar-Zadeh * and Sebastian Magierowski Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science (EECS), Lassonde School of Engineering, York University, Toronto, ON M3J 1P3, Canada; [email protected] (N.M); [email protected] (S.M.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-416-736-2100 Received: 17 April 2019; Accepted: 27 April 2019; Published: 5 June 2019 Abstract: Recent advances of computerized graphical methods have received significant attention for detection and home monitoring of various visual distortions caused by macular disorders such as macular edema, central serous chorioretinopathy, and age-related macular degeneration. After a brief review of macular disorders and their conventional diagnostic methods, this paper reviews such graphical interface methods including computerized Amsler Grid, Preferential Hyperacuity Perimeter, and Three-dimensional Computer-automated Threshold Amsler Grid. Thereafter, the challenges of these computerized methods for accurate and rapid detection of macular disorders are discussed. The early detection and progress assessment of macular disorders can significantly enhance the required clinical procedure for the diagnosis and treatment of macular disorders. Keywords: macular disorders; central serous retinopathy (CSR); graphical macular interface system (GMIS); age-related macular degeneration (AMD) I. Introduction Macular disorders such as myopic maculopathy, macular holes, diabetic macular edema, age- related macular degeneration (AMD), and central serous retinopathy (CSR) cause visual distortion (VD) in their early stages [1,2]. In their advanced phases, macular disorders cause central vision loss. Among these retinal conditions, AMD is the leading cause of blindness and will affect the central vision of 196 million people over the age of 65 worldwide by 2020 [3]. -

The Amsler Chart Is of Doubtful Value in Retinal Screening for Early Laser

Eye (2004) 18, 503–508 & 2004 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0950-222X/04 $25.00 www.nature.com/eye The Amsler chart is FH Zaidi, R Cheong-Leen, EJ Gair, R Weir, CLINICAL STUDY E Sharkawi, N Lee and K Gregory-Evans of doubtful value in retinal screening for early laser therapy of subretinal membranes. The West London Survey Abstract laser therapy, compared with 37% of surveillance nonresponders. Purpose Validating the current protocol of Conclusions The current Amsler chart Amsler chart grid surveillance for the early surveillance protocol is suboptimal for detection of subretinal neovascular membrane detecting SRN in AMD, and a proportion of The Western Eye Hospital (SRN) in age-related macular degeneration cases suitable for early laser therapy may be Marylebone Road (AMD), and investigating its value in missing rapid detection. The results are London, UK facilitating early laser therapy. especially important since recent advances in Methods A retrospective pilot study. Setting: Correspondence: FH Zaidi laser therapy for SRN require early detection central London eye hospital with dedicated Department of for optimal effectiveness. 24-h ophthalmic casualty serving West and Ophthalmology Eye (2004) 18, 503–508. doi:10.1038/sj.eye.6700708 Faculty of Medicine West-central London. Participants: 100 Imperial College London consecutive AMD patients who attended Keywords: Amsler chart; Amsler grid; Laboratory Block casualty with vision loss fulfilling the Charing Cross Campus photodynamic laser therapy; argon laser; following criteria: patients had received and Fulham Palace Road transpupillary thermotherapy; pupillometry; been instructed in the use of Amsler charts London W6 8RF, UK imaging; psychophysical tests; screening; age- Tel: þ 44 20 8383 3696 according to the unit’s dispensation protocol, related macular degeneration Fax: þ 44 20 8383 3651 fluorescein angiography which confirmed new E-mail: fhz12@ SRN.