Municipal Community Services Based Projects in Ntuzuma: an Opportunity for Local Economic Development?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ETHEKWINI MEDICAL HEALTH Facilitiesmontebellomontebello Districtdistrict Hospitalhospital CC 88 MONTEBELLOMONTEBELLO

&& KwaNyuswaKwaNyuswaKwaNyuswa Clinic ClinicClinic MontebelloMontebello DistrictDistrict HospitalHospital CC 88 ETHEKWINI MEDICAL HEALTH FACILITIESMontebelloMontebello DistrictDistrict HospitalHospital CC 88 MONTEBELLOMONTEBELLO && MwolokohloMwolokohlo ClinicClinic (( NdwedweNdwedweNdwedwe CHC CHCCHC && GcumisaGcumisa ClinicClinic CC MayizekanyeMayizekanye ClinicClinic BB && && ThafamasiThafamasiThafamasi Clinic ClinicClinic WosiyaneWosiyane ClinicClinic && HambanathiHambanathiHambanathi Clinic ClinicClinic && (( TongaatTongaatTongaat CHC CHCCHC CC VictoriaVictoriaVictoria Hospital HospitalHospital MaguzuMaguzu ClinicClinic && InjabuloInjabuloInjabuloInjabulo Clinic ClinicClinicClinic A AAA && && OakfordOakford ClinicClinic OsindisweniOsindisweni DistrictDistrict HospitalHospital CC EkukhanyeniEkukhanyeniEkukhanyeni Clinic ClinicClinic && PrimePrimePrime Cure CureCure Clinic ClinicClinic && BuffelsdraaiBuffelsdraaiBuffelsdraai Clinic ClinicClinic && RedcliffeRedcliffeRedcliffe Clinic ClinicClinic && && VerulamVerulamVerulam Clinic ClinicClinic && MaphephetheniMaphephetheni ClinicClinic AA &’&’ ThuthukaniThuthukaniThuthukani Satellite SatelliteSatellite Clinic ClinicClinic TrenanceTrenanceTrenance Park ParkPark Clinic ClinicClinic && && && MsunduzeMsunduze BridgeBridge ClinicClinic BB && && WaterlooWaterloo ClinicClinic && UmdlotiUmdlotiUmdloti Clinic ClinicClinic QadiQadi ClinicClinic && OttawaOttawa ClinicClinic && &&AmatikweAmatikweAmatikwe Clinic ClinicClinic && CanesideCanesideCaneside Clinic ClinicClinic AmaotiAmaotiAmaoti Clinic -

March 2018 Newsletter

From the Rector’s desk Dear Readers Welcome to our first 2018 edition. The 2018 academic year started in the best possible way with the college attaining good students performances in both NCV and Nated programmes. This boosted morale and enthusi- asm to do better for the College. In my opening address, I did share that 2018 is a year of implementation, together we will ensure that Elangeni TVET College becomes the College of choice. Plans for the Business Unit are at an advanced stages. I am pleased that as the institution we heed to the call of being self sustaining to generate revenue for the College. Part of the Business Unit is to forge strategic partnership with public sector, private sector, parastatals, community at large, especially SMME. This partnership are crucial as they play a role in shaping our student’s future in the job market and SMME. I would like to applaud my team that worked tirelessly in establishing part- nership with UIF which will contribute to skilling our nation, especially the youth. As the College it is our motto to improve relations both with internal and external stakeholders. We are also looking forward to the formation of the SRC which will be the mouth piece of our students. Let me further congratulate new students for joining Elangeni TVET family, and hope that they benefitted a lot during the induction programme at all our 8 Campuses. I would also like to applaud well co-ordinated induction by our Student sup- port service for ensuring participation of our social partners like SAPS, HEIADS and more. -

(Gp) Network List Kwazulu-Natal

WOOLTRU HEALTHCARE FUND GENERAL PRACTITIONER (GP) NETWORK LIST KWAZULU-NATAL PRACTICE AREA PROVIDER NAME TELEPHONE ADDRESS NUMBER ABAQULUSI RURAL 433802 DR KHAYELIHLE NXUMALO 034 9330983 A977 GOBINSIMBI ROAD AMANZIMTOTI 683043 DR ROCHAEL DEBIDEEN 031 9038333 SUITE C5, SEADOONE MALL AMANZIMTOTI 1439502 DADA A T 031 9037170 LAGOON CENTRE, SHOP 7, 361 KINGSWAY ROAD AMANZIMTOTI 1489534 BADUL P D 4 SCHOOL CRESCENT BEREA 473758 TIMOL S 031 2092195 420 RANDLES ROAD BEREA 1495879 RANDEREE S E 031 2072872 249 SPARKS ROAD BEREA 1559753 DR KESHUBANANDA NAIDOO 031 2015281 289 MOORE ROAD BERGVILLE 443883 DR WELCOME VEZI 036 4482929 96 SHARRATT STREET BLUFF 328405 NAIDOO A R 031 4661822 SHOP 14, BLUFF SHOPPING CENTRE, 884 BLUFF ROAD BLUFF 1443747 MAHARAJ A S 031 4611002 217 QUALITY STREET BLUFF 1511548 PILLAY S 031 4685360 NATRAJ CENTRE, SHOP 33, BOMBAY WALK BLUFF 448257 KATHRADA M 031 4671631 658 MARINE DRIVE BROOKDALE 1583344 MAHARAJ N 031 5057436 340 CRESTBROOK DRIVE BULWER 70009 DR SIPHO VISAGIE 039 8320250 SHOP 8, STAVCOM CENTRE CATO RIDGE 1526642 ERASMUS P E & PARTNER 031 7822030 CATO MEDICAL CENTRE, 1 RIDGE ROAD CHATSWORTH 5568 DR ARIVAN MOODLEY 031 4035496 215 CROFTDENE DRIVE CHATSWORTH 517585 DR RYNAL DEVANATHAN 98 LENNY NAIDU DRIVE CHATSWORTH 1423819 SEWPERSAD V 031 4092332 211 HIGH TERRACE, CHATWORTH CHATSWORTH 1427180 SHUNMUGAM S M 031 4049014 110 ARENA PARK DRIVE CHATSWORTH 1461885 BADAT M R S 031 4048498 16 MOORTON DRIVE CHATSWORTH 1473131 PILLAY D 031 4048824 62 ROAD 736 CHATSWORTH 1499564 NUNDLALL H INCORPORATED 031 4041319 33 ROAD -

Ward Councillors Pr Councillors Executive Committee

EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE KNOW YOUR CLLR WEZIWE THUSI CLLR SIBONGISENI MKHIZE CLLR NTOKOZO SIBIYA CLLR SIPHO KAUNDA CLLR NOMPUMELELO SITHOLE Speaker, Ex Officio Chief Whip, Ex Officio Chairperson of the Community Chairperson of the Economic Chairperson of the Governance & COUNCILLORS Services Committee Development & Planning Committee Human Resources Committee 2016-2021 MXOLISI KAUNDA BELINDA SCOTT CLLR THANDUXOLO SABELO CLLR THABANI MTHETHWA CLLR YOGISWARIE CLLR NICOLE GRAHAM CLLR MDUDUZI NKOSI Mayor & Chairperson of the Deputy Mayor and Chairperson of the Chairperson of the Human Member of Executive Committee GOVENDER Member of Executive Committee Member of Executive Committee Executive Committee Finance, Security & Emergency Committee Settlements and Infrastructure Member of Executive Committee Committee WARD COUNCILLORS PR COUNCILLORS GUMEDE THEMBELANI RICHMAN MDLALOSE SEBASTIAN MLUNGISI NAIDOO JANE PILLAY KANNAGAMBA RANI MKHIZE BONGUMUSA ANTHONY NALA XOLANI KHUBONI JOSEPH SIMON MBELE ABEGAIL MAKHOSI MJADU MBANGENI BHEKISISA 078 721 6547 079 424 6376 078 154 9193 083 976 3089 078 121 5642 WARD 01 ANC 060 452 5144 WARD 23 DA 084 486 2369 WARD 45 ANC 062 165 9574 WARD 67 ANC 082 868 5871 WARD 89 IFP PR-TA PR-DA PR-IFP PR-DA Areas: Ebhobhonono, Nonoti, Msunduzi, Siweni, Ntukuso, Cato Ridge, Denge, Areas: Reservoir Hills, Palmiet, Westville SP, Areas: Lindelani C, Ezikhalini, Ntuzuma F, Ntuzuma B, Areas: Golokodo SP, Emakhazini, Izwelisha, KwaHlongwa, Emansomini Areas: Umlazi T, Malukazi SP, PR-EFF Uthweba, Ximba ALLY MOHAMMED AHMED GUMEDE ZANDILE RUTH THELMA MFUSI THULILE PATRICIA NAIR MARLAINE PILLAY PATRICK MKHIZE MAXWELL MVIKELWA MNGADI SIFISO BRAVEMAN NCAYIYANA PRUDENCE LINDIWE SNYMAN AUBREY DESMOND BRIJMOHAN SUNIL 083 7860 337 083 689 9394 060 908 7033 072 692 8963 / 083 797 9824 076 143 2814 WARD 02 ANC 073 008 6374 WARD 24 ANC 083 726 5090 WARD 46 ANC 082 7007 081 WARD 68 DA 078 130 5450 WARD 90 ANC PR-AL JAMA-AH 084 685 2762 Areas: Mgezanyoni, Imbozamo, Mgangeni, Mabedlane, St. -

DURBAN NORTH 957 Hillcrest Kwadabeka Earlsfield Kenville ^ 921 Everton S!Cteelcastle !C PINETOWN Kwadabeka S Kwadabeka B Riverhorse a !

!C !C^ !.ñ!C !C $ ^!C ^ ^ !C !C !C!C !C !C !C ^ ^ !C !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ñ !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C !C ^ !C !C $ !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ^ ñ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C ^ ñ ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C $ !C !C ^ !C ^ !C !C !C ñ !C !C !C ^ !C !.ñ ñ!C !C !C !C ^ !C ^ !C ^ !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ ñ !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ ñ !C !C ñ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ñ !C !C ^ ^ !C !C !. !C !C ñ ^ !C ^ !C ñ!C !C ^ ^ !C !C $ ^!C $ ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C !C !C ñ!.^ $ !C !C !C ^ !C !C !C !C $ !C ^ !C !C $ !C !C ñ $ !. !C !C !C !C !C !C !. ^ ñ!C ^ ^ !C $!. ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C !. !C !C ñ!C !C !C !C ^ ñ !C !C ñ !C !C !. ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ñ ^ $ ^ !C ñ !C !C !. ñ ^ !C !. !C !C ^ ñ !. ^ ñ!C !C $^ ^ ^ !C ^ ñ ^ !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C ^ !C $ !C !. ñ !C !C ^ !C ñ!. ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C $!C !. !C ^ !. !. !C !C !. ^ !C !C !C ^ ^ !C !C ñ !C !. -

Following Is a Load Shedding Schedule That People Are Advised to Keep

Following is a load shedding schedule that people are advised to keep. STAND-BY LOAD SHEDDING SCHEDULE Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday Block A 04:00-06:30 08:00-10:30 04:00-06:30 08:00-10:30 04:00-06:30 08:00-10:30 08:00-10:30 Block B 06:00-08:30 14:00-16:30 06:00-08:30 14:00-16:30 06:00-08:30 14:00-16:30 14:00-16:30 Block C 08:00-10:30 16:00-18:30 08:00-10:30 16:00-18:30 08:00-10:30 16:00-18:30 16:00-18:30 Block D 10:00-12:30 12:00-14:30 10:00-12:30 12:00-14:30 10:00-12:30 12:00-14:30 12:00-14:30 Block E 12:00-14:30 10:00-12:30 12:00-14:30 10:00-12:30 12:00-14:30 10:00-12:30 10:00-12:30 Block F 14:00-16:30 18:00-20:30 14:00-16:30 18:00-20:30 14:00-16:30 18:00-20:30 18:00-20:30 Block G 16:00-18:30 20:00-22:30 16:00-18:30 20:00-22:30 16:00-18:30 20:00-22:30 20:00-22:30 Block H 18:00-20:30 04:00-06:30 18:00-20:30 04:00-06:30 18:00-20:30 04:00-06:30 04:00-06:30 Block J 20:00-22:30 06:00-08:30 20:00-22:30 06:00-08:30 20:00-22:30 06:00-08:30 06:00-08:30 Area Block Albert Park Block D Amanzimtoti Central Block B Amanzimtoti North Block B Amanzimtoti South Block B Asherville Block H Ashley Block J Assagai Block F Athlone Block G Atholl Heights Block J Avoca Block G Avoca Hills Block C Bakerville Gardens Block G Bayview Block B Bellair Block A Bellgate Block F Belvedere Block F Berea Block F Berea West Block F Berkshire Downs Block E Besters Camp Block F Beverly Hills Block C Blair Atholl Block J Blue Lagoon Block D Bluff Block E Bonela Block E Booth Road Industrial Block E Bothas Hill Block F Briardene Block G Briardene -

Sheriff Inanda1.Pdf

# # !C # # # # # ^ !C # !.!C # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # !C ^ # # # # # ^ # # # # ^ !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # !C!C # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # !C # # # # # # # !C ^ # # # # # # # # ^ # # # !C # # # # # # # !C # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # !C # !C # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # ^ # !C # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # ^ # # !C # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C !C # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # #!C # # # # # !C # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # ^ # # # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # !C # # # # !C # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # !C # # ## # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # !C # !C # # # # # # ## # !C # !C # # # !C !. # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # ^ # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C !C # ## # # # # # # !C # # # !C # # # # # # # # !C # !C # # # # # ^ # # !C # # # # ^ # # !C # # !C # !C # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # -

Profile of Poverty in the Durban Region

J .. ~ PROFILE OF POVERTY IN THE DURBAN REGION PROJECT FOR STATISTICS ON LIVING STANDARDS AND DEVELOPMENT PREPARED BY J Cobbledick and M Sharratt Economic Research Unit University of Natal Durban OCTOBER 1993 ~, ~' - ( /) .. During 1992 the World Bank approached the Southern Africa Labour and Development Research Unit (SALDRU) at the University of Cape Town to coordinate, a study in South Africa called the Project on Statistics for Living $tandards and Development. This study was carried out during 1993, and consisteci of two phases. The first of these was a situation analysis, consisting of a number of regional poverty profiles and cross-cutting studies on a na~ional level. The second phase was a country wide household surVey conducted in the latter half of 1993. The Project has been built on the Second Carnegie Inquiry into Poverty, which assessed the situation up to the mid 1980's. Whilst preparation of these papers for the situation analysis, using common guidelines, involved much discussion and criticism amongst all those involved in the Project, the final paper remains the responsibility of its authors. .' -<, '" -) 1 In the series of working papers on reilional poverty and cross- '"" . cutting themes there are 12 papers: Regional Poverty Profiles: Ciskei Durban Eastern and Northern Transvaal NatallKwazulu OFS and Qwa-Qwa Port Elizabeth - Uitenhage PWV' Transkei Western Cape Cross-Cutting Studies: Energy Nutrition Urbanisation & Housing Water Supply TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION No. PAGE No. 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 CONTEXTUALISING THE DURBAN -

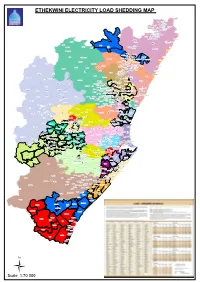

Ethekwini Electricity Load Shedding Map

ETHEKWINI ELECTRICITY LOAD SHEDDING MAP Lauriston Burbreeze Wewe Newtown Sandfield Danroz Maidstone Village Emona SP Fairbreeze Emona Railway Cottage Riverside AH Emona Hambanathi Ziweni Magwaveni Riverside Venrova Gardens Whiteheads Dores Flats Gandhi's Hill Outspan Tongaat CBD Gandhinagar Tongaat Central Trurolands Tongaat Central Belvedere Watsonia Tongova Mews Mithanagar Buffelsdale Chelmsford Heights Tongaat Beach Kwasumubi Inanda Makapane Westbrook Hazelmere Tongaat School Jojweni 16 Ogunjini New Glasgow Ngudlintaba Ngonweni Inanda NU Genazano Iqadi SP 23 New Glasgow La Mercy Airport Desainager Upper Bantwana 5 Redcliffe Canelands Redcliffe AH Redcliff Desainager Matata Umdloti Heights Nellsworth AH Upper Ukumanaza Emona AH 23 Everest Heights Buffelsdraai Riverview Park Windermere AH Mount Moreland 23 La Mercy Redcliffe Gragetown Senzokuhle Mt Vernon Oaklands Verulam Central 5 Brindhaven Riyadh Armstrong Hill AH Umgeni Dawncrest Zwelitsha Cordoba Gardens Lotusville Temple Valley Mabedlane Tea Eastate Mountview Valdin Heights Waterloo village Trenance Park Umdloti Beach Buffelsdraai Southridge Mgangeni Mgangeni Riet River Southridge Mgangeni Parkgate Southridge Circle Waterloo Zwelitsha 16 Ottawa Etafuleni Newsel Beach Trenance Park Palmview Ottawa 3 Amawoti Trenance Manor Mshazi Trenance Park Shastri Park Mabedlane Selection Beach Trenance Manor Amatikwe Hillhead Woodview Conobia Inthuthuko Langalibalele Brookdale Caneside Forest Haven Dimane Mshazi Skhambane 16 Lower Manaza 1 Blackburn Inanda Congo Lenham Stanmore Grove End Westham -

Crime Statistics

CRIME STATISTICS CRIME SITUATION IN REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA TWELVE (12) MONTHS ( APRIL TO MARCH 2018_19) TABLE OF CONTENTS . Introduction . Broad categories of crime . Crime Statistics Analysis . Highlights of the 17 Community-Reported Serious Crimes . National crime overview . Provincial crime overview . Contact Crimes . Kidnapping . Trio crimes . Contact Related Crimes . Property Related Crimes . Other Serious Crimes . Crime Dependent on Police Action . Core Diversion 2 . Environmental Crimes CATEGORIESFinancial year 2017/2018 OF CRIME 17 COMMUNITY REPORTED SERIOUS CRIMES CDPA Contact Contact Property Other Crimes Crime Related Related Serious Dependent on Murder Arson Burglary Theft other Police Action for Detection Attempted Malicious Residential Commercial murder Damage to Burglary Crime Illegal possession of firearms and Assault GBH Property Business Shoplifting ammunition Assault Theft of Motor Drug related crimes Common Vehicle Driving under the Aggravated Theft out/from influence of alcohol Robbery Motor Vehicle and drugs Common Stock Theft Sexual offences Robbery detected as result 3 Sexual Offences of police action NATIONAL CRIME SITUATION APRIL TO MARCH 2018_19 RSA: APRIL TO MARCH 2018_19 CRIME CATEGORY 2009/2010 2010/2011 2011/2012 2012/2013 2013/2014 2014/2015 2015/2016 2016/2017 2017/2018 2018/2019 Case Diff % Change CONTACT CRIMES ( CRIMES AGAINST THE PERSON) Murder 16 767 15 893 15 554 16 213 17 023 17 805 18 673 19 016 20 336 21 022 686 3.4% Sexual Offences 66 992 64 921 60 539 60 888 56 680 53 617 51 895 49 660 50 108 -

Camperdown NU Umzinto NU Inanda NU Inanda NU Lower

New Hanover NU Hoqweni Menyane Mayesweni Hlomantethe Lower Tugela NU KwaHlwemini Sonkonbo/Esigodi Mkhomazi Engoleleni Thongathi Lower Tugela NU Swayimana W osiyane Village Mnamane/ Usuthu Shudu New Hanover NU Emnamane Indaka Mnyameni Umhlali Beach Mambedwini Hengane Mangangeni Mona KwaSokesimbone Ukhalo/Mhlungwini Nqwayini Msunduze Lower Tugela NU Thompson's Bay KwaMophumula Trust Feed Inhlabamkhosi Ndondolo Nobanga Deepdene Makhuluseni Lauriston Deepdale Odlameni Ndwedwe Newtown Ngedleni 6 Burbreeze W ewe Ikhohlwa Sandfield Umsinduzi Mission Reserve Ballito Bay Vuka Nonoti Gcumisa SP Hambanathi Ext 4 Maidstone Village Msilili Mthembeni Magwaveni Pietermaritzburg NU Esthezi Emona SP Fairbreeze Shangase Village Tugela Intaphuka Emona Riverside AH Railway Cottage Ezindlovini Hambanathi Ext 1 Cuphulaka Ziweni Ekhukanyeni W hiteheads Vanrova Gardens Dores Flats Mapumulu SP Mbhukubhu Hillview Tongaat CBD Kwazini Inanda NU Gandhinagar Tongaat Central Ngabayena Ezibananeni Mdlonti Trurolands Mithanagar Maqomgoo Ogunjini Belvedere Imeme 61 W atsonia Tongova M ews Mbhava Mgezanyoni Buffelsdale Chelmsford Heights Tongaat Beach Table Mountain Kwasumubi Nonzila Mbeka Mgezanyoni Inanda Makapane W estbrook Bhulushe Hazelmere Pietermaritzburg NU Amatata Jojweni Gunjini Ngudlintaba New Glasgow Ngonweni Enbuyeni 60 Genazano Cuphulaka Iqadi SP New Glasgow Nkanyezini La M ercy Airport Mdluli SP Abehuzi Amatata Desainager Upper Bantwana Ashburton Training Centre Mlahlanja Mdaphuma Mlahlanja 59 Redcliffe Nkanyezini Canelands Inanda NU 58 Umdloti Heights Ophokweni -

Province Physical Suburb Physical Town Physical

PROVINCE PHYSICAL SUBURB PHYSICAL TOWN PHYSICAL ADDRESS1 PRACTICE NAME CONTACT NUMBER PRACTICE NUMBER KWAZULU-NATAL AMANZIMTOTI AMANZIMTOTI Suite 103 1st Floor Kingsway Hospital BOTHA 0319043563 1525808 KWAZULU-NATAL AMANZIMTOTI AMANZIMTOTI Shop 12 -13 Lagoon Centre DADA 0319037170 1439502 KWAZULU-NATAL AMANZIMTOTI AMANZIMTOTI Suite 205 Netcare Kingsway Hospital HAVEMANN LEIGH D U 0319041394 1452819 KWAZULU-NATAL AMANZIMTOTI AMANZIMTOTI Emergency Dept Netcare Kingsway Hospital HOWLETT 0319043744 1573942 KWAZULU-NATAL AMANZIMTOTI AMANZIMTOTI 6 Ibis Lane HUGO INCORPORATED 0319035040 0278890 KWAZULU-NATAL AMANZIMTOTI AMANZIMTOTI 303 Andrew Zondo Road OETS 0319032301 1493019 KWAZULU-NATAL AMANZIMTOTI AMANZIMTOTI 271 Ipahla Road VAN RENSBURG 0319041313 1461052 KWAZULU-NATAL ATHLONE PARK AMANZIMTOTI Edwin Swales Occupational Centre BADUL 0319042061 1489534 KWAZULU-NATAL ATHLONE PARK AMANZIMTOTI Medexcel Centre Intercare Amanzimtoti BROWN 0319047460 0256005 KWAZULU-NATAL ATHLONE PARK AMANZIMTOTI Medexcel Centre Intercare Amanzimtoti DU PLESSIS 0319047460 1557742 KWAZULU-NATAL ATHLONE PARK AMANZIMTOTI Medexcel Centre DYER, DU PLESSIS AND BROWN INCORPORATED 0319047460 0454419 KWAZULU-NATAL ATHLONE PARK AMANZIMTOTI 30 Prince Street SOOKRAM J 0319045555 0368830 KWAZULU-NATAL ATHLONE PARK AMANZIMTOTI Medexcel Centre TOTIMED 0319041218 1546775 KWAZULU-NATAL KINGSBURGH AMANZIMTOTI 6 Sykes Road JOOSUB N 0319027779 0174270 KWAZULU-NATAL UMBOGINTWINI AMANZIMTOTI Suite 3a Southgate Industrial Park LIEBENBERG 0319144892 1440411 KWAZULU-NATAL TRENANCE PARK