The Recent Four Turnings of Generational Theory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chart Book Template

Real Chart Page 1 become a problem, since each track can sometimes be released as a separate download. CHART LOG - F However if it is known that a track is being released on 'hard copy' as a AA side, then the tracks will be grouped as one, or as soon as known. Symbol Explanations s j For the above reasons many remixed songs are listed as re-entries, however if the title is Top Ten Hit Number One hit. altered to reflect the remix it will be listed as would a new song by the act. This does not apply ± Indicates that the record probably sold more than 250K. Only used on unsorted charts. to records still in the chart and the sales of the mix would be added to the track in the chart. Unsorted chart hits will have no position, but if they are black in colour than the record made the Real Chart. Green coloured records might not This may push singles back up the chart or keep them around for longer, nevertheless the have made the Real Chart. The same applies to the red coulered hits, these are known to have made the USA charts, so could have been chart is a sales chart and NOT a popularity chart on people’s favourite songs or acts. Due to released in the UK, or imported here. encryption decoding errors some artists/titles may be spelt wrong, I apologise for any inconvenience this may cause. The chart statistics were compiled only from sales of SINGLES each week. Not only that but Date of Entry every single sale no matter where it occurred! Format rules, used by other charts, where unnecessary and therefore ignored, so you will see EP’s that charted and other strange The Charts were produced on a Sunday and the sales were from the previous seven days, with records selling more than other charts. -

Smash Hits Volume 34

\ ^^9^^ 30p FORTNlGHTiy March 20-Aprii 2 1980 Words t0^ TOPr includi Ator-* Hap House €oir Underground to GAR! SKias in coioui GfiRR/£V£f/ mjlt< H/Kim TEEIM THAT TU/W imv UGCfMONSTERS/ J /f yO(/ WOULD LIKE A FREE COLOUR POSTER COPY OF THIS ADVERTISEMENT, FILL IN THE COUPON AND RETURN IT TO: HULK POSTER, PO BOXt, SUDBURY, SUFFOLK C010 6SL. I AGE (PLEASE TICK THE APPROPRIATE SOX) UNDER 13[JI3-f7\JlS AND OVER U OFFER CLOSES ON APRIL 30TH 1980 ALLOW 28 DAYS FOR DELIVERY (swcKCAmisMASi) I I I iNAME ADDRESS.. SHt ' -*^' L.-**^ ¥• Mar 20-April 2 1980 Vol 2 No. 6 ECHO BEACH Martha Muffins 4 First of all, a big hi to all new &The readers of Smash Hits, and ANOTHER NAIL IN MY HEART welcome to the magazine that Squeeze 4 brings your vinyl alive! A warm welcome back too to all our much GOING UNDERGROUND loved regular readers. In addition The Jam 5 to all your usual news, features and chart songwords, we've got ATOMIC some extras for you — your free Blondie 6 record, a mini-P/ as crossword prize — as well as an extra song HELLO I AM YOUR HEART and revamping our Bette Bright 13 reviews/opinion section. We've also got a brand new regular ROSIE feature starting this issue — Joan Armatrading 13 regular coverage of the independent label scene (on page Managing Editor KOOL IN THE KAFTAN Nick Logan 26) plus the results of the Smash B. A. Robertson 16 Hits Readers Poll which are on Editor pages 1 4 and 1 5. -

Radio 2 Paradeplaat Last Change Artiest: Titel: 1977 1 Elvis Presley

Radio 2 Paradeplaat last change artiest: titel: 1977 1 Elvis Presley Moody Blue 10 2 David Dundas Jeans On 15 3 Chicago Wishing You Were Here 13 4 Julie Covington Don't Cry For Me Argentina 1 5 Abba Knowing Me Knowing You 2 6 Gerard Lenorman Voici Les Cles 51 7 Mary MacGregor Torn Between Two Lovers 11 8 Rockaway Boulevard Boogie Man 10 9 Gary Glitter It Takes All Night Long 19 10 Paul Nicholas If You Were The Only Girl In The World 51 11 Racing Cars They Shoot Horses Don't they 21 12 Mr. Big Romeo 24 13 Dream Express A Million In 1,2,3, 51 14 Stevie Wonder Sir Duke 19 15 Champagne Oh Me Oh My Goodbye 2 16 10CC Good Morning Judge 12 17 Glen Campbell Southern Nights 15 18 Andrew Gold Lonely Boy 28 43 Carly Simon Nobody Does It Better 51 44 Patsy Gallant From New York to L.A. 15 45 Frankie Miller Be Good To Yourself 51 46 Mistral Jamie 7 47 Steve Miller Band Swingtown 51 48 Sheila & Black Devotion Singin' In the Rain 4 49 Jonathan Richman & The Modern Lovers Egyptian Reggae 2 1978 11 Chaplin Band Let's Have A Party 19 1979 47 Paul McCartney Wonderful Christmas time 16 1984 24 Fox the Fox Precious little diamond 11 52 Stevie Wonder Don't drive drunk 20 1993 24 Stef Bos & Johannes Kerkorrel Awuwa 51 25 Michael Jackson Will you be there 3 26 The Jungle Book Groove The Jungle Book Groove 51 27 Juan Luis Guerra Frio, frio 51 28 Bis Angeline 51 31 Gloria Estefan Mi tierra 27 32 Mariah Carey Dreamlover 9 33 Willeke Alberti Het wijnfeest 24 34 Gordon t Is zo weer voorbij 15 35 Oleta Adams Window of hope 13 36 BZN Desanya 15 37 Aretha Franklin Like -

100 Years: a Century of Song 1970S

100 Years: A Century of Song 1970s Page 130 | 100 Years: A Century of song 1970 25 Or 6 To 4 Everything Is Beautiful Lady D’Arbanville Chicago Ray Stevens Cat Stevens Abraham, Martin And John Farewell Is A Lonely Sound Leavin’ On A Jet Plane Marvin Gaye Jimmy Ruffin Peter Paul & Mary Ain’t No Mountain Gimme Dat Ding Let It Be High Enough The Pipkins The Beatles Diana Ross Give Me Just A Let’s Work Together All I Have To Do Is Dream Little More Time Canned Heat Bobbie Gentry Chairmen Of The Board Lola & Glen Campbell Goodbye Sam Hello The Kinks All Kinds Of Everything Samantha Love Grows (Where Dana Cliff Richard My Rosemary Grows) All Right Now Groovin’ With Mr Bloe Edison Lighthouse Free Mr Bloe Love Is Life Back Home Honey Come Back Hot Chocolate England World Cup Squad Glen Campbell Love Like A Man Ball Of Confusion House Of The Rising Sun Ten Years After (That’s What The Frijid Pink Love Of The World Is Today) I Don’t Believe In If Anymore Common People The Temptations Roger Whittaker Nicky Thomas Band Of Gold I Hear You Knocking Make It With You Freda Payne Dave Edmunds Bread Big Yellow Taxi I Want You Back Mama Told Me Joni Mitchell The Jackson Five (Not To Come) Black Night Three Dog Night I’ll Say Forever My Love Deep Purple Jimmy Ruffin Me And My Life Bridge Over Troubled Water The Tremeloes In The Summertime Simon & Garfunkel Mungo Jerry Melting Pot Can’t Help Falling In Love Blue Mink Indian Reservation Andy Williams Don Fardon Montego Bay Close To You Bobby Bloom Instant Karma The Carpenters John Lennon & Yoko Ono With My -

Smash Hits Volume 33

FORTNIGHTLY March 6-19 1980 i: fcMrstfjg i TH LYING LIZARDS .;! albums STS EDMUNDS )ur GRRk/£V£t/HlfLK HATES 7EEJM THAT TVf^ itav UGLYMONSTERS/ ^A \ / ^ / AAGHi. IF THERE'S ONE THING THATMAKES HULK REALLYAM6RY, IT'S PEOPLE WHO DON'T LOOK AFTER THEIRT€€TH! HULK GOES MAD UNLESS PEOPLE CLEAN THEIR TEETH THOROUGHLY EVERY DAY (ESPECIALLY LAST THING ATNIGHT). HE GOES SSRSfRK IFTHEY DON'T VISITTHE DENTIST REGULARLY! IF YOU D0N7 LOOKAFTER YOUR TEETH, SOMEBODY MAY COME BURSTING INTO YOUR HOUSE IN A TERRIBLE TEMPER AND IT WON'T BE THE MamAM...... 1 ! IF YOU WOULD LIKE A FREE COLOUR POSTER COPY OF THIS ADVERTISEMENT, FlU IN THE COUPON AND RETURN IT TO: HULK POSTER P.O BOX 1, SUDBURY, SUFFOLK COlO 6SL. tAeE(PUASETICKTHEAPPROPRIATEBOir)UNDERI3\Z\i3-l7\3lSANDOVER\JOFFERCLOSESONAPRIL30THmO.AUOW2SDAYSFORDELIVERY(sioaMPmisniA5l}l SH 1 uNAME ADDRESS X. i ^i J4 > March 6-19 1980 Vol 2 No. 5 Phew! Talk about moving ANIMATION mountains — we must have The Skids 4 shifted about six Everests' worth of paper this fortnight, what with ALABAMA SONG your voting forms and Walt David Bowie 4 Jabsco entries. With a bit of luck we'll have the poll results ready SPACE ODDITY forthe next issue but you'll find David Bowie 5 our Jabsco winners on page 26 of this issue. There's also an CUBA incredibly generous Ska Gibson Brothers 8 competition on page 24, not to mention our BIG NEWS! Turn to ALL NIGHT LONG the inside back page and find out Rainbow 14 what we mean . I'VE DONE EVERYTHING FOR YOU Sammy Hagar 14 Managing Editor HOT DOG Nick Logan Shakin' Stevens 17 Editor HOLDIN' -

English Song Booklet

English Song Booklet SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER 100002 1 & 1 BEYONCE 100003 10 SECONDS JAZMINE SULLIVAN 100007 18 INCHES LAUREN ALAINA 100008 19 AND CRAZY BOMSHEL 100012 2 IN THE MORNING 100013 2 REASONS TREY SONGZ,TI 100014 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 100015 2012 IT AIN'T THE END JAY SEAN,NICKI MINAJ 100017 2012PRADA ENGLISH DJ 100018 21 GUNS GREEN DAY 100019 21 QUESTIONS 5 CENT 100021 21ST CENTURY BREAKDOWN GREEN DAY 100022 21ST CENTURY GIRL WILLOW SMITH 100023 22 (ORIGINAL) TAYLOR SWIFT 100027 25 MINUTES 100028 2PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 100030 3 WAY LADY GAGA 100031 365 DAYS ZZ WARD 100033 3AM MATCHBOX 2 100035 4 MINUTES MADONNA,JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE 100034 4 MINUTES(LIVE) MADONNA 100036 4 MY TOWN LIL WAYNE,DRAKE 100037 40 DAYS BLESSTHEFALL 100038 455 ROCKET KATHY MATTEA 100039 4EVER THE VERONICAS 100040 4H55 (REMIX) LYNDA TRANG DAI 100043 4TH OF JULY KELIS 100042 4TH OF JULY BRIAN MCKNIGHT 100041 4TH OF JULY FIREWORKS KELIS 100044 5 O'CLOCK T PAIN 100046 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100045 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100047 6 FOOT 7 FOOT LIL WAYNE 100048 7 DAYS CRAIG DAVID 100049 7 THINGS MILEY CYRUS 100050 9 PIECE RICK ROSS,LIL WAYNE 100051 93 MILLION MILES JASON MRAZ 100052 A BABY CHANGES EVERYTHING FAITH HILL 100053 A BEAUTIFUL LIE 3 SECONDS TO MARS 100054 A DIFFERENT CORNER GEORGE MICHAEL 100055 A DIFFERENT SIDE OF ME ALLSTAR WEEKEND 100056 A FACE LIKE THAT PET SHOP BOYS 100057 A HOLLY JOLLY CHRISTMAS LADY ANTEBELLUM 500164 A KIND OF HUSH HERMAN'S HERMITS 500165 A KISS IS A TERRIBLE THING (TO WASTE) MEAT LOAF 500166 A KISS TO BUILD A DREAM ON LOUIS ARMSTRONG 100058 A KISS WITH A FIST FLORENCE 100059 A LIGHT THAT NEVER COMES LINKIN PARK 500167 A LITTLE BIT LONGER JONAS BROTHERS 500168 A LITTLE BIT ME, A LITTLE BIT YOU THE MONKEES 500170 A LITTLE BIT MORE DR. -

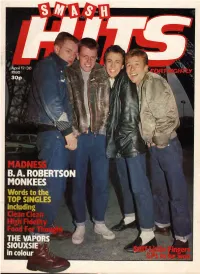

Smash Hits Volume 36

4pril 17-30 ^ 1980 m 30p 1 4. \ t, i% \ '."^.iiam 1 \ # »^» r ,:?^ ) ^ MARNF B. A. ROBERTSON NONKEES THE originals/ The Atlantic Masters — original soul music from the Atlantic label. Ten seven inch E.P.s, each with four tracks and at least two different artists. Taken direct from the original master tapes. Re-cut, Re-issued, Re-packaged. £1.60^ 11168 2 SMASH HITS April 17-30 1980 Vol 2 No. 8 WILL I HOLD IT right there! Now before WHAT DO WITHOUT YOU? you all write in saying how come Lene Lovich 4 there's only four of Madness on CLEAN CLEAN the cover, we'll tell ya. That heap of metalwork in the background The Buggies 5 IS none other than the Eiffel DAYDREAM BELIEVER Tower and the other trois {that's i'our actual French) scarpered off The Monkees 7 up it instead of having their photo MODERN GIRL taken. Now you know why Sheena Easton 8 they're called Madness! More nuttiness can be found on pages SILVER DREAM RACER 12 and 13, and other goodies in David Essex 14 this issue include another chance to win a mini-TV on the I'VE NEVER BEEN IN LOVE crossword, a binder offer for all Suzi Quatro 15 your back issues of Smash Hits CHECK OUT THE GROOVE (page 36), another token towards Mandging Editor your free set of badges (page 35) Nick Logan Bobby Thurston 19 and our great Joe Jackson SEXY EYES competition featuring a chance to Editor himself! (That's Dr. Hook 22 meet the man on Ian Cranna page 28). -

Ackitain'toverpaulcarrackitain'tover Paulcarra Paulcarrackitain'tover

ackItAin’tOverPaulCarrackItAin’tOverPaulCarrackItAin’tOverPaulCarra 1.SheLivedDownTheStreet 2.Nothin’ToLose 3.ItAin’tOver 4.HappyToSeeYouAgain 5.WhereDidIGoWrong? 6.EmptySpace 7.OneSmallStep 8.Forever 9.NeverTooLate 10.JustALittleLie 11.Ain’tNoLove BonusTracks 12.Georgia 13.LoveWillKeepUsAlive 14.AnyDayNow 15.TheLivingYears 12 - 14: Live from the Royal Albert Hall concert, 2002 12: Featuring Rod Argent on piano 15: Live from Abbey Road Featuring the London Community Gospel Choir www.paulcarrack.net PCARiT5 P2014 Carrack-UK. g2014 Carrack-UK. Unauthorised copying, reproduction, hiring, lending, public performance and broadcasting prohibited. All rights reserved. Unauthorised duplication is a violation of applicable laws. veDownTheStreetSheLivedDownTheStreetSheLivedDownTheStreetSheLiv SheLivedDownTheStreet She lived down the street / They shared the same school / Their lives intertwined like two balls of wool / And love was the word that never saw them rest / On this family tree they found themselves a nest / She grew up with him, right into their teens / He got his first job and entered her dreams / Their love was on fire each word on the flame / On this family tree they carved out one name / A lifetime of love in each others heart / She walked through his life along the same path / They married and moved into a new house / Their roots were put down and friends came around / This peaceful retreat became full of life / On their family tree a family sleeps tonight / A lifetime of love in each others heart / She walked through his life along -

Songs by Title

16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Songs by Title 16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Title Artist Title Artist (I Wanna Be) Your Adams, Bryan (Medley) Little Ole Cuddy, Shawn Underwear Wine Drinker Me & (Medley) 70's Estefan, Gloria Welcome Home & 'Moment' (Part 3) Walk Right Back (Medley) Abba 2017 De Toppers, The (Medley) Maggie May Stewart, Rod (Medley) Are You Jackson, Alan & Hot Legs & Da Ya Washed In The Blood Think I'm Sexy & I'll Fly Away (Medley) Pure Love De Toppers, The (Medley) Beatles Darin, Bobby (Medley) Queen (Part De Toppers, The (Live Remix) 2) (Medley) Bohemian Queen (Medley) Rhythm Is Estefan, Gloria & Rhapsody & Killer Gonna Get You & 1- Miami Sound Queen & The March 2-3 Machine Of The Black Queen (Medley) Rick Astley De Toppers, The (Live) (Medley) Secrets Mud (Medley) Burning Survivor That You Keep & Cat Heart & Eye Of The Crept In & Tiger Feet Tiger (Down 3 (Medley) Stand By Wynette, Tammy Semitones) Your Man & D-I-V-O- (Medley) Charley English, Michael R-C-E Pride (Medley) Stars Stars On 45 (Medley) Elton John De Toppers, The Sisters (Andrews (Medley) Full Monty (Duets) Williams, Sisters) Robbie & Tom Jones (Medley) Tainted Pussycat Dolls (Medley) Generation Dalida Love + Where Did 78 (French) Our Love Go (Medley) George De Toppers, The (Medley) Teddy Bear Richard, Cliff Michael, Wham (Live) & Too Much (Medley) Give Me Benson, George (Medley) Trini Lopez De Toppers, The The Night & Never (Live) Give Up On A Good (Medley) We Love De Toppers, The Thing The 90 S (Medley) Gold & Only Spandau Ballet (Medley) Y.M.C.A. -

4KQ's Sizzling 70S Weekend

4KQ's Sizzling 70s Weekend A GLASS OF CHAMPAGNE SAILOR A LITTLE RAY OF SUNSHINE AXIOM A MATTER OF TIME RAILROAD GIN ABSOLUTELY RIGHT FIVE MAN ELECTRICAL ANGIE ROLLING STONES ANNABELLE DANIEL BOONE ARIZONA MARK LINDSAY BABY BLUE BADFINGER BAND ON THE RUN PAUL McCARTNEY/WINGS BANG BANG BA ROBERTSON BARRACUDA HEART BELIEVE IT JUST LIKE ME AZTECS BEST OF MY LOVE EAGLES BLACK BETTY RAM JAM BLACK WATER DOOBIE BROTHERS BLINDED BY THE LIGHT MANFRED MANNS EARTH BAND BLUE CHEVROLET BALLERINA ROSS RYAN BORN TO RUN BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN BORN WITH A SMILE ON MY FACE STEPHANIE DE SYKES CALLING OCCUPANTS CARPENTERS CAN THE CAN SUZI QUATRO CARRY THAT WEIGHT COLLEEN HEWETT CHICAGO GRAHAM NASH CHILDREN OF THE REVOUTION T-REX CHILD'S PLAY SHERBET CINDY INCIDENTLY FACES COCAINE J.J. CALE COLD AS ICE FOREIGNER COME AND GET IT BADFINGER COME BACK AGAIN DADDY COOL COME ON FEEL THE NOIZE SLADE CRACKLIN' ROSIE NEIL DIAMOND CROCODILE ROCK ELTON JOHN CRUEL TO BE KIND NICK LOWE DAISY MAE HAMILTON, JOE FRANK & REYNOLDS DANCE WITH ME ORLEANS DAY AFTER DAY BADFINGER DECEMBER 1963 FOUR SEASONS DEPARTMENT OF YOUTH ALICE COOPER DEVIL GATE DRIVE SUZI QUATRO DO WHAT YOU DO AIR SUPPLY DO YA ELECTRIC LIGHT ORCHESTRA DOCTOR'S ORDERS CAROL DOUGLAS DON'T FALL IN LOVE FERRETS DON'T GO BREAKING MY HEART ELTON JOHN /KIKI DEE DON'T STOP FLEETWOOD MAC DREAM WEAVER GARY WRIGHT EASY COMMODORES/LIONEL RITCHIE EBONY EYES BOB WELCH EGO (IS NOT A DIRTY WORD) SKYHOOKS EVERY LITTLE BIT HURTS SHIRLEY STRACHAN EVERY TIME I THINK OF YOU BABYS FAREWELL AUNTY JACK GRAHAME BOND FAT BOTTOMED GIRLS -

Host's Master Artist List for Game 1

Host's Master Artist List for Game 1 You can play the list in the order shown here, or any order you prefer. Tick the boxes as you play the songs. Paula Abdul Donny Osmond Level 42 Culture Club Gabrielle Livin Joy Moloko Tommy Steel Gloria Gaynor John Travolta MC Hammer Samantha Fox Pat Benatar Clash Grace Jones Blondie Dina Carroll D Ream Soft Cell Hanson M People Eddie Cochran Tiffany Joycelyn Brown Georgie Fame B52s Black Box Ugly Kid Joe Osmonds Stevie Wonder Bjork Toyah Whitney Houston Police ELO BA Robertson Europe Jimi Hendrix Troggs Specials Wurzels The Farm James Al Green Showaddywaddy Dolly Parton East 17 Nirvana Byrds Billy Jo Spears Copyright QOD Page 1/53 Host's Master Artist List for Game 2 You can play the list in the order shown here, or any order you prefer. Tick the boxes as you play the songs. Jimi Hendrix Huey Lewis & The News Aretha Franklin Hue & Cry Spandau Ballet Erasure Kiss Dolly Parton Lulu Jimmy Ruffin Police Kirsty McColl Transvision Vamp Peter Andre Mis-Teeq Natalie Imbruglia P J Proby Phil Collins Kool & The Gang Gerry & The Pacemakers Sonny & Cher Foreigner Cyndi Lauper Bruce Springsteen Vic Reeves Village People Steve Harley Reef Boyz II Men Contours Snap Frankie Valli Suzi Quatro Men At Work Aswad Eminem Bon Jovi Ken Dodd Morrissey Betty Boo Surviver Thompson Twins Visage Genesis London Beat Inxs T.Rex Aerosmith Eagles Soul II Soul Copyright QOD Page 2/53 Host's Master Artist List for Game 3 You can play the list in the order shown here, or any order you prefer. -

Homestar Karaoke Song Book

HomeStar Karaoke Songs by Artist Karaoke Shack Song Books Title DiscID Title DiscID 10cc Avril Lavigne Good Morning Judge HSW216-04 Sk8er Boi HSW001-07 2 Play B.A. Robertson So Confused HSW022-10 Bang Bang HSG011-08 50 Cent Bang Bang HSW215-01 In Da Club HSG005-05 Knocked It Off HSG011-10 In Da Club HSW013-06 Knocked It Off HSW215-04 50 Cent & Nate Dogg Kool In The Kaftan HSG011-11 21 Questions HSW013-01 Kool In The Kaftan HSW215-05 ABBA To Be Or Not To Be HSG011-12 Chiquitita HSW257-01 To Be Or Not To Be HSW215-09 Chiquitita SFHS104-01 B.A. Robertson & Maggie Bell Dancing Queen HSW251-04 Hold Me HSG011-09 Does Your Mother Know HSW252-01 Hold Me HSW215-02 Fernando HSW257-03 B2K & P. Diddy Fernando SFHS104-02 Bump, Bump, Bump HSW001-02 Gimme Gimme Gimme (A Man After Midnight) HSW257-04 Baby Bash Gimme Gimme Gimme (A Man After Midnight) SFHS104-04 Suga Suga HSW024-09 I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do HSW252-03 Bachelors, The I Have A Dream HSW258-01 Chapel In The Moonlight HSW205-03 I Have A Dream SFHS104-05 I Wouldn't Trade You For The World HSW205-09 Knowing Me, Knowing You HSW257-07 Love Me With All Of Your Heart HSW206-02 Knowing Me, Knowing You SFHS104-06 Ramona HSW206-06 Mama Mia HSW251-07 Bad Manners Money, Money, Money HSW252-05 Buona Sara HSW204-02 Name Of The Game, The HSW258-09 Hey Little Girl HSW204-05 Name Of The Game, The SFHS104-13 Just A Feeling HSG011-03 S.O.S.