Engaging Residents' Groups in Planning Using Focus Groups

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

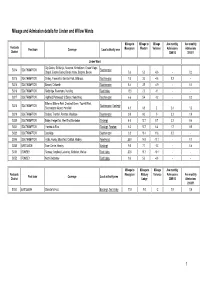

Mileage and Admissions

Mileage and Admission details for Linden and Willow Wards Mileage to Mileage to Mileage Ave monthly Ave monthly Postcode Post town Coverage Local authority area Moorgreen Western Variance Admissions Admissions District 2009/10 2010/11 Linden Ward City Centre, St. Mary's, Newtown, Nicholstown, Ocean Village, SO14 SOUTHAMPTON Southampton Chapel, Eastern Docks, Bevois Valley, Bargate, Bevois 5.6 5.0 -0.6 - 0.2 SO15 SOUTHAMPTON Shirley, Freemantle, Banister Park, Millbrook, Southampton 7.6 3.0 -4.6 0.2 - SO16 SOUTHAMPTON Bassett, Chilworth Southampton 8.4 3.5 -4.9 - 0.1 SO16 SOUTHAMPTON Redbridge, Rownhams, Nursling Test Valley 13.0 2.0 -11 - - SO17 SOUTHAMPTON Highfield, Portswood, St Denys, Swaythling Southampton 6.6 5.4 -1.2 - 0.2 Bitterne, Bitterne Park, Chartwell Green, Townhill Park, SO18 SOUTHAMPTON Southampton , Eastleigh Southampton Airport, Harefield 4.5 6.5 2 2.4 1.2 SO19 SOUTHAMPTON Sholing, Thornhill, Peartree, Woolston Southampton 9.0 9.0 0 3.2 1.9 SO30 SOUTHAMPTON Botley, Hedge End, West End, Bursledon Eastleigh 4.0 12.7 8.7 2.2 0.4 SO31 SOUTHAMPTON Hamble-le-Rice Eastleigh , Fareham 6.3 12.7 6.4 1.7 0.5 SO32 SOUTHAMPTON Curdridge Southampton 3.8 15.4 11.6 0.2 - SO45 SOUTHAMPTON Hythe, Fawley, Blackfield, Calshot, Hardley New Forest 25.9 14.8 -11.1 - 0.1 SO50 EASTLEIGH Town Centre, Hamley Eastleigh 9.0 7.7 -1.3 - 0.6 SO51 ROMSEY Romsey, Ampfield, Lockerley, Mottisfont, Wellow Test Valley 20.8 10.7 -10.1 - - SO52 ROMSEY North Baddesley Test Valley 9.6 5.0 -4.6 - - Mileage to Mileage to Mileage Ave monthly Postcode Moorgreen Melbury Variance Admissions Ave monthly Post town Coverage Local authority area District Lodge 2009/10 Admissions 2010/11 SO53 EASTLEIGH Chandler's Ford Eastleigh , Test Valley 11.0 9.0 -2 1.8 0.6 1 Mileage to Mileage to Mileage Ave monthly Ave monthly Postcode Post town Coverage Local authority area Moorgreen Western Variance Admissions Admissions District 2009/10 2010/11 Willow Ward City Centre, St. -

Policing Southampton Partnership Briefing

Policing Southampton Partnership briefing September 2019 Southampton is a vibrant, busy city that we are all proud to protect and serve. This newsletter is for our trusted partners with the aim to bring you closer to the teams and the people that identify risk, tackle offenders and protect those who most need our help. We will list the challenges we are facing, the problems we are solving, and opportunities to work together. Operation Sceptre We took part in Operation Sceptre which was a national week of action that ran from September 16 to 22. In Southampton we demonstrated our commitment through several engagement events, proactive patrols, visits to parents of young people thought be carrying knives, and we conducted knife sweeps. In Shirley, a PCSO hosted a live, two hours engagement session on Twitter and the team carried out a test purchase operation in four retail outlets. All shops passed which is great news. Through our focus on high harm, we stopped and searched a man who was in possession of an axe and he was charged. We also ar- rested a man after he was reported to be making threats towards his ex partner with a knife. Most notably, a man was reported to have committed three knife point robberies in the centre of Southampton, he was quickly arrested, charged and remanded. For us to be able try and influence young people and prevent the next generation from carrying knives, we produced a campaign via the Police Apprentice Scheme in partnership with schools and the Saints Foundation and asked children come up with an idea that they thought would make their peers aged 9 to 14 think twice about choosing to carry a knife. -

PREACHING PLACES and MEETING HOUSES a Provisional Gazetteer of Nineteenth-Century Protestant Nonconformity in Southampton by Veronica Green

PREACHING PLACES AND MEETING HOUSES A Provisional Gazetteer of Nineteenth-Century Protestant Nonconformity in Southampton By Veronica Green Nineteenth-century nonconformists were prone to rebellion and revival, to schism and secession. New congregations arose by division from an existing church, by the missionary efforts of travelling preachers, by the inspiration of charismatic evangelists. They met in rooms over pubs and workshops, in scaffold lofts and converted laundries. They rented the Victoria Rooms, of the Philharmonic Hall, or Mr Monk’s Schoolroom, until they could build for themselves, or come into an inheritance from another denomination moving on to better things, or failing to keep up the payments on an ambitious building. Some of the back-street chapels and the smaller groups played “musical chapels” well into this century. This is a chapel gazetteer, in that it lists nonconformist places of worship. It is not only a list of chapels, that is, buildings used exclusively for worship, but also of known meeting rooms and private houses used for worship. It attempts to trace the history of worshippers as well as the buildings they worshipped in, and for the moment it concentrates on the old borough before the boundary extensions in 1895. It excludes the French Protestant congregation at St Julian’s, which had conformed in the eighteenth century, and Roman Catholics, who were listed as “nonconformists” in nineteenth-century directories, but would not now be so described. Basic sources, other than those mentioned in the text, are: Directories 1803-1899 Appendix A: Buildings used as Methodist places of worship, in The story of St Andrew’s Methodist Church, Sholing, by James W M Brown, Sholing Press, 1995 Willis, Arthur J: A Hampshire Miscellany, Vol. -

U6H Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

U6H bus time schedule & line map U6H Highƒeld View In Website Mode The U6H bus line (Highƒeld) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Highƒeld: 11:35 PM (2) Lordswood: 6:01 AM - 10:35 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest U6H bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next U6H bus arriving. Direction: Highƒeld U6H bus Time Schedule 27 stops Highƒeld Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 11:35 PM Monday 11:35 PM Southampton Nocs, Eastern Docks Tuesday 11:35 PM Platform Tavern, Town Quay Wednesday 11:35 PM Telephone House, Town Quay Thursday 11:35 PM High Street, Southampton Friday 11:35 PM Holyrood Church, Southampton City Centre 135 High Street, Southampton Saturday 11:35 PM Westquay, Southampton City Centre Portland Terrace, Southampton Asda & Marlands, Southampton City Centre U6H bus Info Direction: Highƒeld Civic Centre, Southampton City Centre Stops: 27 Windsor Terrace, Southampton Trip Duration: 27 min Line Summary: Southampton Nocs, Eastern Docks, Park Walk, Southampton City Centre Platform Tavern, Town Quay, Telephone House, Town Quay, Holyrood Church, Southampton City Centre, Solent University, Southampton City Centre Westquay, Southampton City Centre, Asda & Marlands, Southampton City Centre, Civic Centre, Rsh Hospital, Nicholstown Southampton City Centre, Park Walk, Southampton St Marys Road, Southampton City Centre, Solent University, Southampton City Centre, Rsh Hospital, Nicholstown, Denzil Avenue, Denzil Avenue, Bevois Valley Bevois Valley, Aldi Store, Bevois Valley, Spring 54 Onslow -

Public Transport

Travel Destinations and Operators Operator contacts Route Operator Destinations Monday – Saturday Sunday Bus operators Daytime Evening Daytime Bluestar Quay Connect Bluestar Central Station, WestQuay, Town Quay 30 mins 30 mins 30 mins 01202 338421 Six dials 1 Bluestar City Centre, Bassett, Chandlers Ford, Otterbourne, Winchester 15 mins 60 mins 30 mins www.bluestarbus.co.uk B1 Xelabus Bitterne, Sholing, Bitterne 3 per day off peak (Mon, Weds, Fri) City Red and First Solent Premier National Oceanography Centre, Town Quay, City Centre, Central 0333 014 3480 Inn U1 Uni-link 7/10 mins 20 mins 15 mins Station, Inner Avenue, Portswood, University, Swaythling, Airport www.cityredbus.co.uk Night service. Leisure World, West Quay, Civic Centre, London Road, 60 mins U1N Uni-link Royal South Hants Hospital, Portswood, Highfield Interchange, (Friday and Saturday nights) Salisbury Reds Airport, Eastleigh 01202 338420 City Centre, Inner Avenue, Portswood, Highfield, Bassett, W1 Wheelers 30/60 mins www.salisburyreds.co.uk W North Baddesley, Romsey I N T O N ST City Centre, Inner Avenue, Portswood, Swaythling, North Stoneham, 2 Bluestar 15 mins 60 mins 30 mins Eastleigh, Bishopstoke, Fair Oak Uni-link 2 First City Red City Centre, Central Station, Shirley, Millbrook 8/10 mins 20 mins 15 mins 023 8059 5974 www.unilinkbus.co.uk B2 Xelabus Bitterne, Midanbury, Bitterne 3 per day off peak (Mon, Weds, Fri) U2 Uni-link City Centre, Avenue Campus, University, Bassett Green, Crematorium 10 mins 20 mins 20 mins Wheelers Travel 023 8047 1800 3 Bluestar City Centre, -

GREEN NEWS Portswood

GREEN NEWS Katherine Barbour Local Green Party Portswood Candidate WORKING HARD ALL YEAR ROUND Did you know that cycling exposes us to the least pollution on our commute? It is also the best for our health so a WIN- WIN Jack’s Story The recent decision to not implement Die-In at the Bargate a Clean Air Zone is bad news for No Clean Air Zone – people like Jack in Bitterne. He has Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary shame on our City Disease (COPD) and struggles to Southampton City Council were breathe when he comes into the city. proposing to create a clean air zone, The air quality in parts of the city is charging lorries, buses and taxis to getting worse and little is being done enter the city. This proposal is to address this. Jack says, “you can’t expected to be thrown out by the see it, you are breathing it all the Labour council. This means we will time” continue breathing polluted air. To The Green Party has a set of policies highlight this many people to tackle this; stopping airport demonstrated at the Bargate on expansion, ensuring cruise liners plug Saturday 12th January – this was in in, expanding bus routes and memory of the 110 people who die building safe cycle routes in the city prematurely from poor air each year in our city –many more struggle every day with breathing difficulties. I believe SCC should reconsider implementing a clean air zone – 56% of respondents to the clean air consultation were in favour - and not buckle under the pressure from businesses and politicians. -

Public Consultation GP Practice Premises In

Public Consultation GP practice premises in Southampton City Centre May 2016 Contents The case for change ................................................................ 3 The current service at the Bargate Medical Centre ................ 4 Our proposal for future services ............................................. 6 What about staff? ................................................................... 7 Why are we consulting? ......................................................... 7 Why happens next? ................................................................ 8 How can I give my views? ....................................................... 9 2 The case for change St Mary’s Surgery is committed to improving the health and wellbeing of the people of Southampton. The main practice team is based in a purpose built two-story accommodation in the St Mary’s district of the city, adjacent to the City Centre and Docks. The practice also provides services from two branch surgeries: Telephone House Surgery and the Bargate Medical Centre. Telephone House Surgery is in the historic French Quarter of the City and was opened in February 2009. The Bargate Medical Centre is positioned at the rear of the Boots store on Above Bar Street and can be accessed from the store. The premises at the Bargate Medical Centre were very much a short term solution to deal with issues around accessibility of the previous Oxford Street Surgery premises. Accessibility at the Bargate Medical Centre remains a major issue. The premises at the Bargate Medical Centre are not fit for 21st century healthcare, and cannot be expanded to make them fit for the future. This consultation is about exploring options around relocating the services provided at the Bargate Medical Centre within St Mary’s Surgery and Telephone House Surgery. 3 The current service at the Bargate Medical Centre In September 2013 the Care Quality Commission, the independent regulator of health and adult social care in England, reviewed the premises at the Bargate Medical Centre. -

2 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

2 bus time schedule & line map 2 Eastleigh View In Website Mode The 2 bus line (Eastleigh) has 4 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Eastleigh: 7:50 AM - 8:50 PM (2) Eastleigh: 11:02 PM (3) Fair Oak: 12:30 AM - 11:20 PM (4) Southampton City Centre: 4:56 AM - 10:09 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 2 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 2 bus arriving. Direction: Eastleigh 2 bus Time Schedule 37 stops Eastleigh Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 11:45 PM Monday 7:50 AM - 8:50 PM Bargate, Southampton City Centre 6 Hanover Buildings, Southampton Tuesday 7:50 AM - 8:50 PM Above Bar, Southampton City Centre Wednesday 7:50 AM - 8:50 PM 93 Above Bar Street, Southampton Thursday 7:50 AM - 8:50 PM Cenotaph, Southampton City Centre Friday 7:50 AM - 8:50 PM Above Bar Street, Southampton Saturday 7:50 PM - 8:50 PM Giddy Bridge, Bedford Place 41 London Road, Southampton Law Courts, Bedford Place 2 bus Info Archers Road, Banister Park Direction: Eastleigh Stops: 37 Stag Gates, Banister Park Trip Duration: 34 min 144 Lodge Road, Southampton Line Summary: Bargate, Southampton City Centre, Above Bar, Southampton City Centre, Cenotaph, Cedar Road, Portswood Southampton City Centre, Giddy Bridge, Bedford 98-100 Lodge Road, Southampton Place, Law Courts, Bedford Place, Archers Road, Banister Park, Stag Gates, Banister Park, Cedar Spring Crescent, Portswood Road, Portswood, Spring Crescent, Portswood, 51 Portswood Road, Southampton Waitrose, Portswood, Portswood Broadway, Portswood, Sainsbury, Portswood, -

Drugs Problem, Albion Towers, St Mary's, Southampton

Tilley Award 2003 Operation Acer Drugs Problem, Albion Towers, St Mary's, Southampton. Consideration for the category of Partnership. Hampshire Constabulary. Authorising Officer: Acting ACCTO Graham Wyeth Mr S Smith, Area Housing Manager, Southampton City Council Mr R Honey, Community Safety Team Contact Details: Sergeant Dick Partridge Community Beat Sergeant Southampton Central Police Station Havelock Road Southampton Hampshire SOW 4 7LG Tell: 023 8067 4368 Fax: 023 8867 4370 OPERATION ACER - Drugs problem, Albion Towers - Summary Forcer Hampshire Constabulary Contact: Sgt Dick Partridge 02380 674368 Nature of the problem Albion Towers is a 15 storey block of flats, situated on the inner city council estate of Golden Grove within the St Marys area of Southampton. There has been a long history of drug related crime within the St Marys area, particularly linked to Albion Towers. At least three addresses were known to be dealing drugs and users came from both in and out of the city meaning that many 'shot up"in the vicinity, including the stair areas of the block and in bushed areas on the lacal estate. Thus the problem was not only of dealers but also of the drug related litter left behind, including needles. Evidence of the problem There has always been drug related problems within Albion Towers and Golden Grove, however in the summer of 2002 the two wardens, who live and work in Albion Towers became increasingly concerned about the amount of drug litter in the stair areas. They were collecting up to 3 bucket fulls of rubbish each day, containing needles, blood swabs, tin foil, matches and ofcourse the associated litter of sweet, crisp wrappers. -

Ward Councilors: (See Also Google Map)

Ward Councilors: (See also Google Map) Name Ward/Next standing Party Councillor Sarah Bogle Bargate ‘18 L Councillor John Noon Bargate ‘19 L Councillor Darren Paffey Bargate ‘20 L Councillor Beryl Harris Bassett ‘18 C Councillor Les Harris Bassett ‘19 C Councillor John Hannides Bassett ‘20 C Councillor Derek Burke Bevois ‘18 L Councillor Jacqui Rayment Bevois ‘19 L Councillor Stephen Barnes-Andrews Bevois ‘20 L Councillor Simon Letts Bitterne ‘18 L Councillor John Jordan Bitterne ‘19 L Councillor Frances Murphy - New Bitterne ‘20 L Councillor John Inglis Bitterne Park ‘18 C Councillor David Fuller Bitterne Park ‘19 C Councillor Ivan White Bitterne Park ‘20 C Councillor Keith Morrell Coxford ’18 IL Councillor Don Thomas Coxford ‘19 IL Councillor Tammy Thomas - New Coxford ‘20 IL Councillor Jeremy Moulton Freemantle ‘18 C Councillor Brian Parnell Freemantle ‘19 C Councillor David Shields Freemantle ‘20 L Councillor Val Laurent - New Harefield ‘18 C Councillor Daniel Fitzhenry Harefield ‘19 C Councillor Peter Baillie Harefield ‘20 C Councillor Mike Denness Millbrook ‘18 L Councillor David Furnell Millbrook ‘19 L Councillor Sarah Taggart - New Millbrook ‘20 L Councillor Paul Lewzey Peartree ‘18 L Councillor Alex Houghton Peartree ‘19 C Councillor Eammonn Keogh Peartree ‘20 L Councillor Paul O’Neill Portswood ‘18 C Councillor Matthew Claisse Portswood ‘19 C Councillor John Savage - New Portswood ‘20 L Councillor Cathie McEwing Redbridge ‘18 L Councillor Andrew Pope Redbridge ‘19 IL Councillor Lee Whitbread Redbridge ‘20 L Councillor Hannah Coombs Shirley ‘18 L Councillor Satvir Kaur Shirley ‘19 L Councillor Mark Chaloner Shirley ’20 L Councillor Nigel Hecks Sholing ‘18 C Councillor Graham Wilkinson Sholing ‘19 C Councillor James Baillie - New Sholing ‘20 C Councillor Bob Painton Swaythling ‘18 C Councillor Spiros Vassiliou Swaythling ‘19 C Councillor Sharon Mintoff Swaythling ‘20 L Councillor Sue Blatchford Woolston ‘18 L Councillor Warwick Payne Woolston ‘19 L Councillor Christopher Hammond Woolston ‘20 L . -

Final Recommendations on the Future Electoral Arrangements for Southampton in Hampshire

Final recommendations on the future electoral arrangements for Southampton in Hampshire Report to the Secretary of State for the Environment, Transport and the Regions July 2000 LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND This report sets out the Commission’s final recommendations on the electoral arrangements for the city of Southampton in Hampshire. Members of the Commission are: Professor Malcolm Grant (Chairman) Professor Michael Clarke CBE (Deputy Chairman) Peter Brokenshire Kru Desai Pamela Gordon Robin Gray Robert Hughes CBE Barbara Stephens (Chief Executive) © Crown Copyright 2000 Applications for reproduction should be made to: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office Copyright Unit. The mapping in this report is reproduced from OS mapping by the Local Government Commission for England with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, © Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Licence Number: GD 03114G. This report is printed on recycled paper. Report no: 165 ii LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND CONTENTS page LETTER TO THE SECRETARY OF STATE v SUMMARY vii 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 CURRENT ELECTORAL ARRANGEMENTS 5 3 DRAFT RECOMMENDATIONS 9 4 RESPONSES TO CONSULTATION 11 5 ANALYSIS AND FINAL RECOMMENDATIONS 13 6 NEXT STEPS 29 APPENDIX A Draft Recommendations for Southampton (January 2000) 31 A large map illustrating the proposed ward boundaries for Southampton is inserted inside the back cover of this report. LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND iii iv LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND Local Government Commission for England 25 July 2000 Dear Secretary of State On 20 July 1999 the Commission began a periodic electoral review of Southampton under the Local Government Act 1992. -

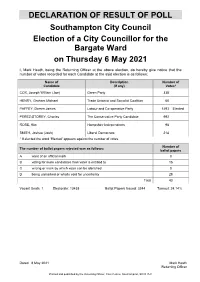

Declaration of Result of Poll

DECLARATION OF RESULT OF POLL Southampton City Council Election of a City Councillor for the Bargate Ward on Thursday 6 May 2021 I, Mark Heath, being the Returning Officer at the above election, do hereby give notice that the number of votes recorded for each Candidate at the said election is as follows: Name of Description Number of Candidate (if any) Votes* COX, Joseph William (Joe) Green Party 338 HENRY, Graham Michael Trade Unionist and Socialist Coalition 66 PAFFEY, Darren James Labour and Co-operative Party 1493 Elected PEREZ-STOREY, Charles The Conservative Party Candidate 992 ROSE, Kim Hampshire Independents 98 SMITH, Joshua (Josh) Liberal Democrats 214 * If elected the word 'Elected' appears against the number of votes. Number of The number of ballot papers rejected was as follows: ballot papers A want of an official mark 0 B voting for more candidates than voter is entitled to 15 C writing or mark by which voter can be identified 0 D being unmarked or wholly void for uncertainty 28 Total 43 Vacant Seats: 1 Electorate: 13438 Ballot Papers Issued: 3244 Turnout: 24.14% Dated 8 May 2021 Mark Heath Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Civic Centre, Southampton, SO14 7LY DECLARATION OF RESULT OF POLL Southampton City Council Election of a City Councillor for the Bassett Ward on Thursday 6 May 2021 I, Mark Heath, being the Returning Officer at the above election, do hereby give notice that the number of votes recorded for each Candidate at the said election is as follows: Name of Description Number of Candidate (if any) Votes* BLACKMAN, Richard Liberal Democrat 1373 GORE, Stephen George (Steve) Green Party 204 HANNIDES, John Michael Local Conservatives 1795 Elected MARX, Michael (Mike) Trade Unionist and Socialist Coalition 24 MINTO, Ashley Mark Labour Party 614 * If elected the word 'Elected' appears against the number of votes.