An Overview of Lead and Accompaniment Separation in Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music Standards

5th Grade Singing alone and with others Standard 1 Students sing alone or in groups, on pitch and in rhythm, using good tone, diction, breath control, and posture while maintaining a steady tempo. They sing from memory a variety of song repertoire, including ostinatos, partner songs, rounds, and music of many cultures and styles. They sing accurately with appropriate dynamics, breath control, phrasing, and interpretation. Students in fifth grade sing in groups, blending vocal sounds, matching dynamics, and following the conductor. 5.1.1 Sing warm-ups that stress diction, posture, and an appropriate singing tone. 5.1.2 Sing a round with appropriate dynamics, phrasing and interpretations. Maintain an independent part and keep a steady beat. 5.1.3 Sing a memorized song in a foreign language. 5.1.4 Follow the conductor. Playing an instrument alone and with others Standard 2 Students perform accurately, independently, and expressively on an instrument, either alone or in an ensemble. They echo easy rhythmic, melodic, and chordal patterns. Students perform in groups, blending instrumental tones, matching dynamics, and responding to the conductor. They perform instrumental parts while other students sing or play different parts. 5.2.1 Play an ostinato part independently. 5.2.2 Play a melody or rhythm in the proper tempo, using appropriate dynamics. 5.2.3 Play an accompaniment to a class or group song. Example: On a keyboard, guitar, mallet instrument, or autoharp, play an ostinato pattern while the group sings. 5.2.4 Play a variety of music of various cultures and styles. 5.2.5 Maintain an independent part on an instrument in a group while following the conductor. -

Guitar Best Practices Years 1, 2, 3 and 4 Nafme Council for Guitar

Guitar Best Practices Years 1, 2, 3 and 4 Many schools today offer guitar classes and guitar ensembles as a form of music instruction. While guitar is a popular music choice for students to take, there are many teachers offering instruction where guitar is their secondary instrument. The NAfME Guitar Council collaborated and compiled lists of Guitar Best Practices for each year of study. They comprise a set of technical skills, music experiences, and music theory knowledge that guitar students should know through their scholastic career. As a Guitar Council, we have taken careful consideration to ensure that the lists are applicable to middle school and high school guitar class instruction, and may be covered through a wide variety of method books and music styles (classical, country, folk, jazz, pop). All items on the list can be performed on acoustic, classical, and/or electric guitars. NAfME Council for Guitar Education Best Practices Outline for a Year One Guitar Class YEAR ONE - At the completion of year one, students will be able to: 1. Perform using correct sitting posture and appropriate hand positions 2. Play a sixteen measure melody composed with eighth notes at a moderate tempo using alternate picking 3. Read standard music notation and play on all six strings in first position up to the fourth fret 4. Play melodies in the keys C major, a minor, G major, e minor, D major, b minor, F major and d minor 5. Play one octave scales including C major, G major, A major, D major and E major in first position 6. -

Classical Music from the Late 19Th Century to the Early 20Th Century: the Creation of a Distinct American Musical Sound

Portland State University PDXScholar Young Historians Conference Young Historians Conference 2019 May 1st, 12:30 PM - 1:45 PM Classical Music from the Late 19th Century to the Early 20th Century: The Creation of a Distinct American Musical Sound Ashley M. Christensen Lakeridge High School Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians Part of the Music Theory Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Christensen, Ashley M., "Classical Music from the Late 19th Century to the Early 20th Century: The Creation of a Distinct American Musical Sound" (2019). Young Historians Conference. 13. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians/2019/oralpres/13 This Event is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Young Historians Conference by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. CLASSICAL MUSIC FROM THE LATE 19th CENTURY TO THE EARLY 20th CENTURY: THE CREATION OF A DISTINCT AMERICAN MUSICAL SOUND Marked by the conflict of the Civil War, the late 19th century of American history marks an extremely turbulent time for the United States of America. As the young nation reached the second half of the century, idle threats of a Southern secession from the union bloomed into an all-encompassing conflict. However, through the turbulence of the war, American music persisted. Strengthened in battle, the ideas of a reconstructed American national identity started to form a distinctly different American culture and way of life. This is reflected in the nation’s shift in the music written after the war. -

RECITATIVE STYLE and the FIGURFD BASS THESIS Presented

/O i0 A COURSE IN KEYBOAIO AIMOBy BASED ON THE RECITATIVE STYLE AND THE FIGURFD BASS THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State Teachers College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By George S. Thompson, B. M. 158610 Garland, Texas August, 1948 158610 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ILLUSTFAJTIO.S., Page . 9 , 9 0 v Chapter I. INTRODUCTION . * , " 4 4 . , Statement of the Problem Need for the Study Sources and Validity of Data Method of Presentation II. YIGUREDBASS . * 0 g , * ." 4 III. RECITATIVE . IV. TRIADS . * 0 0* * , I * 13 Root Position of Triads First Inversion of Triads Second Inversion of Triads Modulation V. NON-IARMONIC TONES * * , 9 a 9 , 0 , . The Passing Tone The Suspension The Neighboring Tone The Anticipation The Escape Tone The Appoggiatura The Pedal Point VI. SEVENTH CHORDS . * . * * * . , 43 The Dominant Seventh Chord The Supertonic Seventh Chord The Leading Tone Seventh Chord in Minor The Subdominant Seventh Chord The Tonic Seventh Chord in Major VII* ALTERED CHORDS. .. Altered Chords in Minor Altered Chords in Major 6ii Chapter Page VIII. THE CHORD OF TIE AUGEEIN SIXTH . 58 IX. MODULATIONTO FOREIGNaYS . 61 x. REVIEW . 64 BIBLIOGRAPHY . 67 iv LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Example of the Figurations for the Triad in Root Position . 14 2. Example of the Figurations for the First Inversion of Triads . 21 3. Example of the Figurations for the Second Inversion of Triads . 24 4. Example of the Figurations for the Passing Tone . 29 5. Example of the Figurations for the Suspension . , . 32 6. -

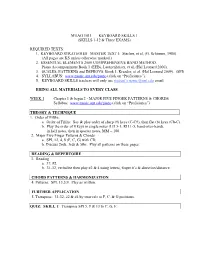

MUAG 1011 KEYBOARD SKILLS 1 (SKILLS 1-12 & Three EXAMS)

MUAG 1011 KEYBOARD SKILLS 1 (SKILLS 1-12 & Three EXAMS) REQUIRED TEXTS: 1. KEYBOARD STRATEGIES MASTER TEXT I: Stecher, et al, (G. Schirmer, 1980). (All pages are KS unless otherwise marked.) 2. ESSENTIAL ELEMENTS 2000 COMPREHENSIVE BAND METHOD, Piano Accompaniment Book 1 (EEB), Lautzenheiser, et al, (Hal Leonard 2000). 3. SCALES, PATTERNS and IMPROVS, Book 1, Kreader, et al, (Hal Leonard 2009). (SPI) 4. SYLLABUS: www.music.unt.edu/piano (click on “Proficiency”). 5. KEYBOARD SKILLS teachers will only use student’s name @unt.edu email. BRING ALL MATERIALS TO EVERY CLASS. WEEK 1 Chapter 1 & begin 2 - MAJOR FIVE FINGER PATTERNS & CHORDS Syllabus: www.music.unt.edu/piano (click on “Proficiency”) THEORY & TECHNIQUE 1. Order of Fifths: a. Order of Fifths: Say & play order of sharp (#) keys (C-C#), then flat (b) keys (Cb-C). b. Play the order of # keys in single notes (LH 5-1; RH 1-5, hand-over-hand), in half notes, then in quarter notes, MM = 100 2. Major Five Finger Patterns & Chords a. SPI, 12, 4, 8 (F, C, G) with CD. b. Discuss 2nds, 3rds & 5ths. Play all patterns on these pages. READING & REPERTOIRE 3. Reading a. 37, #2. b. 31-32, verbalize then play #2 & 4 using letters, finger #’s & direction/distance. CHORD PATTERNS & HARMONIZATION 4. Patterns: SPI, 13,5,9. Play as written. FURTHER APPLICATION 5. Transpose: 31-32, #2 & #4 by intervals to F, C, & G positions. QUIZ: SKILL 1: Transpose SPI 5, 9 & 13 to C, G, F. WEEK 2 Complete Chapter 2 - MAJOR FIVE FINGER PATTERNS & CHORDS THEORY & TECHNIQUE 1. -

Melody and Accompaniment Articles for EPMOW (Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World) by Philip Tagg

P Tagg: 1 Melody and Accompaniment articles for EPMOW (Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World) by Philip Tagg Contents melody 2 Defining parameters 2 General characteristics of popular melody 2 Metaphorical nomenclature 3 Typologies of melody 4 Structural typologies 4 Pitch contour 4 Tonal vocabulary 7 Dynamics and mode of articulation 8 Rhythmic profile 8 Body and melodic rhythm 9 Language and melodic rhythm 9 Culturally specific melodic formulae 10 Patterns of recurrence 12 Connotative typologies 15 accompaniment 17 Bibliography 20 Musical references 22 P Tagg: melody Defining parameters 2 melody From the two Ancient Greek words mélos (m°low = a song, or the music to which a song is set) and ode (”dÆ = ode, song, poem), the English word melody seems to have three main meanings: [1] a monodic tonal sequence, accompanied or unaccom- panied, perceived as a musical statement with distinct rhythmic profile and pitch contour; [2] the monodic musical foreground to which ACCOMPANIMENT (see p.17 ff.) and HARMONY (see Tagg’s Harmony Handout) are, at least within most popular music traditions of Europe and the Americas, understood as providing the back- ground; [3] all such monodic tonal sequences and/or aspects of musical foreground within one complete song (e.g. ‘Auld Lang Syne is a popular Scottish melody’). It should be noted in the latter case that mélodie, Melodie, melodia, melodi (French, German, Latin and Scandinavian languages respectively) can in popular parlance sometimes denote the entirety of any TUNE or SONG (including lyrics and accompa- niment) in which melody, defined according to [1] and [2] above, is a prominent fea- ture. -

A Cappella – Choral Music Without Instrumental Accompaniment

MUSIC VOCABULARY TERMS A Cappella – Choral music without instrumental accompaniment Accelerando – (accel.) Gradually increasing in speed Adagio – Slowly, leisurely Allargando – Gradually slower, louder and broader Allegretto – Light and cheerful, faster than moderato, slower than allegro Allegro – Lively, brisk, rapid Andante – In a moderately slow time, flowing easily and gracefully Animato – With life and animation Antagonist – person who opposes, fights or competes with another opponent or rival Aperture – hole or opening in an instrument Arco – to be played with the bow Aria – a solo song (in an opera) expressing a character’s feelings Baroque Period – This time period lasted from the 1600 – 1750. The main elements of this time period were complexity and ornamentation. The music seemed to curl and twist with elaborate detail. Two main musical forms appeared in this time period orchestral music and opera. Some of the greatest composers of this time period were Handel, Bach, Vivaldi, Monteverdi, and Purcell. Bell – cup shaped flared opening at the end of a brass or woodwind instrument Blues – (1930s) style of music originating in the Mississippi Delta region, features guitar, soulful sound, use of blue notes and introduction of the singer Boogie Woogie – (1920s) used primarily piano, repeating pattern in bass line (left hand) with syncopated choral melody in treble (right hand), dance oriented Book Musical – A type of musical in which the characters act out the plot which leads to a clear outcome. Book musicals can be either Musical -

Guitar Audition Requirements

Prospective students may do a classical guitar OR jazz guitar audition. Please see audition requirements below. Prospective students wishing to audition in a different style of music (such as rock, blues, country, bluegrass, or pop) are welcome, and may contact Dr. Fowler directly ([email protected]) to discuss alternative requirements. Classical guitar audition: Undergraduate classical guitar audition: 1) Perform two contrasting compositions such as: -A composition from the Renaissance or Baroque period -A composition from the Classical or Romantic period -A composition from the 20th or 21st Century 2) Scales and fret-board harmony !Play the following scales-two octaves: C major, C harmonic minor,! C melodic minor, and C chromatic. ! Play two voicings of the following chords in C and G: major, minor, major 7th, dominant 7th, minor 7th, half diminished 7th, and diminished 7th. Graduate classical guitar audition: 1) Perform three contrasting compositions 2) Scales and fret-board harmony ! Play the following scales-two octaves in any key: major, harmonic minor,! melodic minor, whole-tone, and chromatic.! Four voicings for each of the following chords in any key: major, minor, major 7th, dominant 7th, minor 7th, half diminished 7th, and diminished 7th. Jazz guitar audition: Undergraduate jazz guitar audition 1) Perform two contrasting jazz compositions such as: -Blues !-Up-tempo standard -Ballad At least one composition must be with performed with a backing track and must demonstrate the ability to play the melody (head), the accompaniment (comping), and improvise (solo). 2) Scales and fret-board harmony ! Play the following scales-two octaves: C major, C harmonic minor, C melodic minor, and C chromatic. -

2Music of the Middle Ages

M usic of the Middle Ages 2Elizabeth Kramer 2.1 OBJECTIVES 1. Demonstrate knowledge of historical and cultural contexts of the Middle Ages 2. Recognize musical styles of the Middle Ages 3. Identify important genres and uses of music of the Middle Ages 4. Identify aurally, selected compositions of the Middle Ages and critically evaluate its style 5. Compare and contrast music of the Middle Ages with today’s contemporary music 2.2 KEY TERMS AND INDIVIDUALS • a cappella • drone • Alfonso the Wise • gothic • bubonic plague • Guillaume de Machaut • cadence • Hildegard of Bingen • cathedrals • hymn • Catholic Church • mass • chant • melisma • classical Greece and Rome • Middle Ages (450-1400 CE) • clergy • nobility • commoners • Perotin • courtly love • polyphony • courts • Pope • Crusades • Pythagoras Page | 34 UNDERSTANDING MUSIC MUSIC OF THE MIDDLE AGES • refrain • syllabic • rhythm according to the text • university • Roman Empire (27 BCE – 476 CE) • vernacular literatures • song • verse • strophes • Virgin Mary 2.3 INTRODUCTION AND HISTORICAL CONTEXT 2.3.1 Musical Timeline Events in History Events in Music 2nd millennia BCE: First Hebrew Psalms are written 7th Century BCE: Ancient Greeks and Romans use music for entertainment and religious rites 6th Century BCE: Pythagoras and his experi- ments with acoustics From the 1st Century CE: Spread of Christianity through the Roman Empire 4th Century BCE: Plato and Aristotle write 4th Century CE: Founding of the monastic about music movement in Christianity c. 400 CE: St Augustine writes about church c. 450 CE: Fall of Rome music 4th – 9th Century CE: Development/Codification of Christian Chant c. 800 CE: First experiments in Western Music 11th Century CE: Rise of Feudalism & the Three Estates 11th Century CE: Guido of Arezzo refines of mu- 11th Century: Growth of Marian Culture sic notation and development of solfège 1088 CE: Founding of the University of Bolo- gna 12th Century CE: Hildegard of Bingen writes c. -

Repeated Musical Patterns

SECONDARY/KEY STAGE 3 MUSIC – HOOKS AND RIFFS 5 M I N UTES READING Repeated Musical Patterns 5 MINUTES READING #1 Repetition is important in music where sounds or sequences are often “Essentially my repeated. While repetition plays a role in all music, it is especially prominent contribution was to in specific styles. introduce repetition into Western music “Repetition is part and parcel of symmetry. You may find a short melody or a as the main short rhythm that you like and you repeat it through the course of a melody or ingredient without song. This sort of repetition helps to unify your melody and serves as an any melody over it, identifying factor for listeners. However, too much of a good thing can get without anything just patterns, annoying. If you repeat a melody or rhythm too often, it will start to bore the musical patterns.” listener”. (Miller, 2005) - Terry Riley “Music is based on repetition...Music works because we remember the sounds we have just heard and relate them to ones that are just now being played. Repetition, when done skillfully by a master composer, is emotionally satisfying to our brains, and makes the listening experience as pleasurable as it is”. (Levitin, 2007) During the Eighteenth Century, musical concerts were high-profile events and because someone who liked a piece of music could not listen to it again, musicians and composers had to think of a way to make the music ‘sink in’. Therefore, they would repeat parts of their songs or music at times, making Questions to think about: their music repetitive, without becoming dull. -

Music Vocabulary a Cappella. Unaccompanied Choral Singing

Music Vocabulary A cappella. Unaccompanied choral singing. Accompaniment. A vocal or solo part that supports or is background for a solo part. Articulation. In performance, the characteristics of attack and decay of tones and the manner and extent to which tones in sequence are connected or disconnected. Atonal. Music in which no single tone is the home base or key center. Bar. A unit of music, such as 12-bar or 8-bar, denoting length. Beat. A unit of measure in rhythmic time. Binary. A musical form consisting of two main sections. Cadence. A group of notes or chords at the end of a phrase or piece of music that gives a feeling of pausing or finality. Cadenza. A parenthetic flourish in a solo piece commonly just before a final or other important cadence. Canon. A musical form in which melody is imitated exactly in one or more parts, similar to a round. Chord. Three or more tones played simultaneously. Classroom instruments. Instruments typically used in the general music classroom, including, for example, recorder-type instruments, chorded zithers, mallet instruments, simple percussion instruments, fretted instruments, keyboard instruments, and electronic instruments. Coda. A "tail" or short closing section added at the end of a piece of music. Compose. To create original music by organizing sound. Usually written down for others to perform. Composition. A single, complete piece of music, (also , piece and work). Compound meter. Meter characterized by 3:1 relationship of the beat to the subdivided beat (the note receiving the beat in compound meter is always a dotted note.). -

![Arxiv:2001.02360V3 [Cs.SD] 27 Apr 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0906/arxiv-2001-02360v3-cs-sd-27-apr-2021-1900906.webp)

Arxiv:2001.02360V3 [Cs.SD] 27 Apr 2021

Automatic Melody Harmonization with Triad Chords: A Comparative Study Yin-Cheng Yeh, Wen-Yi Hsiao, Satoru Fukayama, Tetsuro Kitahara, Benjamin Genchel, Hao-Min Liu, Hao-Wen Dong, Yian Chen, Terence Leong, and Yi-Hsuan Yang ARTICLE HISTORY Compiled April 28, 2021 ABSTRACT Several prior works have proposed various methods for the task of automatic melody harmonization, in which a model aims to generate a sequence of chords to serve as the harmonic accompaniment of a given multiple-bar melody sequence. In this paper, we present a comparative study evaluating and comparing the performance of a set of canonical approaches to this task, including a template matching based model, a hidden Markov based model, a genetic algorithm based model, and two deep learning based models. The evaluation is conducted on a dataset of 9,226 melody/chord pairs we newly collect for this study, considering up to 48 triad chords, using a standardized training/test split. We report the result of an objective evaluation using six different metrics and a subjective study with 202 participants. KEYWORDS Symbolic music generation; automatic melody harmonization; functional harmony 1. Introduction Automatic melody harmonization, a sub-task of automatic music generation (Fern´andez& Vico, 2013), refers to the task of creating computational models that can generate a harmonic accompaniment for a given melody (Chuan & Chew, 2007; Simon, Morris, & Basu, 2008). Here, the term harmony, or harmonization, is used to refer to chordal accompaniment, where an accompaniment is defined relative to the melody as the supporting section of the music. Figure 1 illustrates the inputs and outputs for a melody harmonization model.