From Chaiwala to Chowkidar: Modi's Election Campaigns Online and Offline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Dalits Want... ‘You Are Dalits, Politics in Uttar Pradesh, There Nate Delay in Courts While Are Around 65 Dalit Castes Seeking Justice

February 28, 2019 Justice. Liberty. Fraternity. Equality www.dalitpost.com Brick workers demand end to bondage In many cases, Brick kiln workers pass on their debt and poverty to their chil- dren, who end up working at the brick kilns and very often in inhuman con- ditions..... Dalit Post - page 8 What Dalits in India want... - page 2 I don’t want to be a Divisive policies chowkidar... undermining growth - pg 3 - page 4 Image credit: Courtesy Satish Acharya The BJP’s do A taste of his or die own return medicine? battle in - page 7 of the the Brahmin? Northeast... - Saeed Naqvi -page 11 - Sujit Chakraborty -page 12 Do facts As usual, BJP Poor add up to Athawale suppressed representation Yogi’s senses a Dalits, of women in claims? kill.... Backward NE politics... communities... - page 9 -page 13 -page 14 -page 15 Much, Much More Inside! For free private circulation Atrocities... Dalit POST www.dalitpost.com February 28, 2019 2 What Dalits want... ‘You are Dalits, politics In Uttar Pradesh, there nate delay in courts while are around 65 Dalit castes seeking justice. And they is for us’ “You are Dalits. You all who fall under the Sched- see justice delayed as jus- are downtrodden. You uled Caste (SC) category. tice denied. So, they want belong to Scheduled In the districts of eastern this to change. Castes. Politics is for us UP, their population var- In UP, there are more (Kammas). The leader- ies between 16% and 40% than 40 Dalit communities ship posts are reserved of the total SC population. -

Amit Shah at Parivartan Yatra Rally in Mysore

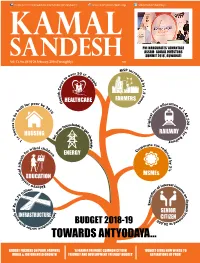

https://www.facebook.com/Kamal.Sandesh/ www.kamalsandesh.org @kamalsandeshbjp PM INAUGURAtes ‘ADVANTAGE ASSAM- GLOBAL INVESTORS SUMMit 2018’, GUWAHATI Vol. 13, No. 04 16-28 February, 2018 (Fortnightly) `20 HEALTHCARE FARMERS HOUSING RAILWAY ENERGY MSMEs EDUCATION SENIOR INFRASTRUCTURE BUDGET 2018-19 CITIZEN TOWARDS ANTYODAYA... BUDGET FOCUSES ON POOR, FARMERS ‘A FARMER FRIENDLY, COMMON CITIZEN ‘BUDGET GIVES NEW WINGS TO RURAL & JOB ORIENTED GROWTH FRIENDLY AND DEVELOPMENT FRIENDLY BUDGEt’ 16-28 FEBRUARY,ASP IRATIONS2018 I KAMAL OF P SANDESHoor’ I 1 Karnataka BJP welcomes BJP National President Shri Amit Shah at Parivartan Yatra Rally in Mysore. BJP National President Shri Amit Shah hoisting the tri-colour on the 69th Republic Day celebration at BJP HQ, New Delhi. BJP National President Shri Amit Shah paying floral tributes Shri Amit Shah addressing the SARBANSDANI to to Sant Ravidas ji on his Jayanti at BJP H.Q. in New Delhi commemorate the 350th birth anniversary of Guru Gobind 2 I KAMAL SANDESH I 16-28 FEBRUARY, 2018 Singh ji at Chandani Chowk, New Delhi. Fortnightly Magazine Editor Prabhat Jha Executive Editor Dr. Shiv Shakti Bakshi Associate Editors Ram Prasad Tripathy Vikash Anand Creative Editors Vikas Saini Mukesh Kumar Phone +91(11) 23381428 FAX +91(11) 23387887 BUDGET FOCUSES ON POOR, FARMERS RURAL & JOB E-mail ORIENTED GROWTH [email protected] Finance Minister Shri Arun Jaitley presented on February 1, 2018 general [email protected] 06 Budget 2018-19 in Parliament. It was second time the budget was Website: www.kamalsandesh.org presented on first of February instead following colonial era practices of... VAICHARIKI 17 C M SIDDARAMAIAH SYNONYMOUS WITH Aspects of Economics 21 CORRUPTION: AMIT SHAH BJP National President Shri SHRADHANJALI Amit Shah said Karnataka CM Siddaramaiah was synonymous Chintaman Vanga / Hukum Singh 23 with corruption and added 15 CONGRESS GOVERNMENT that the state government was ARTICLE IN KARNATAKA IS ON EXIT protecting the killers of Hindu.. -

Election Campaigning in a Transformed India

TIF - Election Campaigning in a Transformed India MANJARI KATJU June 7, 2019 Waiting in line to vote | Al Jazeera English/Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0) The Lok Sabha elections of 2019 are being held in a country that is very different from what it was in 2009 and 2014. What are political parties offering the new electorate? What will the outcome reveal of the transformation that has taken place? A Changed Context The general elections of 2019 are being held in an India which has been transformed in multifarious ways. To state the obvious, India has undergone a big change over the past three decades. Stating this fact and noting its specificities is important to understand the nature of electoral campaigning today. This is an India where more than half of the population is below 25 years and two-thirds is less than 35 (Sharma 2017); the middle class is growing, though the estimates of the size of the middle class vary, ranging from 5% - 6% to 25% - 30% of India’s population (Jodhka and Prakash 2016: 7); Census data (2011) shows that more than 30% of India’s population lives in urban areas, the number could be much higher if one were to look at satellite data and relax the official definition of an urban settlement (Sreevatsan 2017); the number of smart- phone users is expected to double from 404.1 million in 2017 to 829 million in 2022 (IANS 2018); agriculture’s share in GDP has declined to as little as 15% (Statistics Times 2019); and the number of people drawing sustenance from agriculture and allied activities has come down to about 56% (Census data 2011), this would be even lower if one only looks at those with agriculture as their primary occupation in 2018-19. -

Standing Committee on Information Technology (2016-17)

STANDING COMMITTEE ON INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY (2016-17) 34 SIXTEENTH LOK SABHA MINISTRY OF INFORMATION AND BROADCASTING DEMANDS FOR GRANTS (2017-18) THIRTY-FOURTH REPORT LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI March, 2017/ Phalguna, 1938 (Saka) THIRTY-FOURTH REPORT STANDING COMMITTEE ON INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY (2016-17) (SIXTEENTH LOK SABHA) MINISTRY OF INFORMATION AND BROADCASTING DEMANDS FOR GRANTS (2017-18) Presented to Lok Sabha on 09.03.2017 Laid in Rajya Sabha on 10.03.2017 LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI March, 2017/ Phalguna, 1938 (Saka) CONTENTS Page COMPOSITION OF THE COMMITTEE (iii) ABBREVIATIONS (iv) INTRODUCTION (v) REPORT PART I I. Introductory 1 II. Mandate of the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting 1 III. Implementation status of recommendations of the Committee contained in the 2 Twenty-third Report on Demands for Grants (2016-17) IV. Twelfth Five Year Plan Fund Utilization 3 V. Budget (2016-17) Performance and Demands for Grants 2017-18) 4 VI. Broadcasting Sector 11 a. Allocation to Prasar Bharati and its Schemes 12 b. Grant in aid to Prasar Bharati for Kisan Channel 21 c. Financial Performance of AIR and DD (2016-17) 23 d. Action taken on Sam Pitroda Committee Recommendations 28 e. Main Secretariat Schemes under Broadcasting Sector 31 VII. Information Sector 48 a. Indian Institute of Mass Communication (IIMC) 51 b. Directorate of Advertising and Visual Publicity (DAVP) 56 c. Direct Contact Programme by Directorate of Field Publicity 65 VIII. Film Sector 69 a. National Museum of Indian Cinema (Film Division) 73 b. Infrastructure Development Programmes Relating to Film sector 75 c. Development Communication & Dissemination of Filmic Content 79 d. -

KPMG FICCI 2013, 2014 and 2015 – TV 16

#shootingforthestars FICCI-KPMG Indian Media and Entertainment Industry Report 2015 kpmg.com/in ficci-frames.com We would like to thank all those who have contributed and shared their valuable domain insights in helping us put this report together. Images Courtesy: 9X Media Pvt.Ltd. Phoebus Media Accel Animation Studios Prime Focus Ltd. Adlabs Imagica Redchillies VFX Anibrain Reliance Mediaworks Ltd. Baweja Movies Shemaroo Bhasinsoft Shobiz Experential Communications Pvt.Ltd. Disney India Showcraft Productions DQ Limited Star India Pvt. Ltd. Eros International Plc. Teamwork-Arts Fox Star Studios Technicolour India Graphiti Multimedia Pvt.Ltd. Turner International India Ltd. Greengold Animation Pvt.Ltd UTV Motion Pictures KidZania Viacom 18 Media Pvt.Ltd. Madmax Wonderla Holidays Maya Digital Studios Yash Raj Films Multiscreen Media Pvt.Ltd. Zee Entertainmnet Enterprises Ltd. National Film Development Corporation of India with KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”), a Swiss entity. All rights reserved. entity. (“KPMG International”), a Swiss with KPMG International Cooperative © 2015 KPMG, an Indian Registered Partnership and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms Partnership KPMG, an Indian Registered © 2015 #shootingforthestars FICCI-KPMG Indian Media and Entertainment Industry Report 2015 with KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”), a Swiss entity. All rights reserved. entity. (“KPMG International”), a Swiss with KPMG International Cooperative © 2015 KPMG, an Indian Registered Partnership and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms Partnership KPMG, an Indian Registered © 2015 #shootingforthestars: FICCI-KPMG Indian Media and Entertainment Industry Report 2015 Foreword Making India the global entertainment superpower 2014 has been a turning point for the media and entertainment industry in India in many ways. -

GLOBAL HUMANITIES Year 6, Vol

8 GLOBAL HUMANITIES Year 6, Vol. 8, 2021 – ISSN 2199–3939 Editors Frank Jacob and Francesco Mangiapane Identity and Nationhood Editorial by Texts by Frank Jacob and Francesco Mangiapane Amrita De Sophie Gueudet Frank Jacob Udi Lebel and Zeev Drori edizioni Museo Pasqualino edizioni Museo Pasqualino direttore Rosario Perricone GLOBAL HUMANITIES 8 Biannual Journal ISSN 2199-3939 Editors Frank Jacob Nord Universitet, Norway Francesco Mangiapane University of Palermo, Italy Scientific Board GLOBAL HUMANITIES Jessica Achberger Dario Mangano Year 6, Vol. 8, 2021 – ISSN 2199–3939 University of Lusaka, Zambia University of Palermo, Italy Editors Frank Jacob and Francesco Mangiapane Giuditta Bassano Gianfranco Marrone IULM University, Milano, Italy University of Palermo, Italy Saheed Aderinto Tiziana Migliore Western Carolina University, USA University of Urbino, Italy Bruce E. Bechtol, Jr. Sabine Müller Angelo State University, USA Marburg University, Germany Stephan Köhn Rosario Perricone Cologne University, Germany University of Palermo, Italy 8 GLOBAL HUMANITIES Year 6, Vol. 8, 2021 – ISSN 2199–3939 Editors Frank Jacob and Francesco Mangiapane Identity and Nationhood Editorial by Texts by Frank Jacob and Francesco Mangiapane Amrita De Sophie Gueudet Frank Jacob Udi Lebel and Zeev Drori edizioni Museo Pasqualino https://doi.org/10.53123/GH_8_5 Masculinities in Digital India Trolls and Mediated Affect Amrita De SUNY Binghamton [email protected] Abstract. This article analyzes the proliferation of post-2014 social media trolling in In- dia assessing how a pre-planned virtually mediated affective deployment produces phys- ical ramifications in real spaces. I first unpack Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s hyper-masculine social media figuration; then study the generative impact of brand Modi Masculinity through a processual affective rendering regulated by hired social media in- fluencers and digital media strategists. -

Rahul Regrets Misquoting SC

Follow us on: facebook.com/dailypioneer RNI No.2016/1957, REGD NO. SSP/LW/NP-34/2019-21 @TheDailyPioneer instagram.com/dailypioneer/ Established 1864 OPINION 8 WORLD 12 SPORT 15 Published From MONEY RULES US TO SANCTION NATIONS FOR NEYMAR RETURNS AS DELHI LUCKNOW BHOPAL BHUBANESWAR IMPORTING IRANIAN OIL RANCHI RAIPUR CHANDIGARH THE ROOST PSG BEAT MONACO 3-1 DEHRADUN HYDERABAD VIJAYWADA Late City Vol. 155 Issue 109 LUCKNOW, TUESDAY APRIL 23, 2019; PAGES 16 `3 *Air Surcharge Extra if Applicable ARSHAD IS UNDERSTATED: VIDYA} BALAN } 14 VIVACITY www.dailypioneer.com Rahul regrets misquoting SC But Cong president repeats ‘Chowkidar chor’ hai in Amethi PNS n NEW DELHI/AMETHI formation campaign” being led of executive power and a lead- by senior BJP functionaries as ing example of the corruption ongress president Rahul well as the Government that of the BJP Government led by CGandhi on Monday the December 14 last year Prime Minister Modi, which expressed regret in the judgment gave a “clean chit” to deserves to be investigated Supreme Court over his the Modi Government on the thoroughly by a Joint remarks attributing certain Rafale deal. Parliamentary Committee and comments against Prime He also referred to a media proceeded against thereafter”. Minister Narendra Modi on the interview by Prime Minister Away from the SC pro- basis of a recent order of the top Narendra Modi in which he ceedings, Rahul once again court in the Rafale deal case, had said the apex court had raked up his often-repeated but wasted no time in repeat- given a clean chit to the poll theme of alleged corrup- ing his “Chowkidar chor” jibe Government in the Rafale deal. -

View, He Set the Standards of Debate in Parliament

Exclusive Focus ge fudy iM+sa gSa ç.k djds] viuk ru&eu viZ.k djds ftn gS ,d lw;Z mxkuk gS] vEcj ls Åapk tkuk gS ,d Hkkjr u;k cukuk gS] ,d Hkkjr u;k cukuk gS -ujsUæ eksnh The Prime Minister’s address on the occasion of the 72nd Independence Day from the ramparts of the historic Red Fort laid out the great pace with which India has transformed over the last 4 years. Through mentioning developments of several government initiatives, the government led by PM Modi has moved significantly from ‘policy paralyses’ to a ‘reform, perform and transform’ approach. Some of the key highlights of the speech includes:- The Constitution of India given to us by Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar has spoken about justice for all. The recently concluded Parliament session was one devoted to 1 social justice. The Parliament session witnessed the passage of the bill to create an OBC Commission. Dial 1922 to hear www.mygov.in 1 PM Narendra Modi’s https://transformingindia.mygov.in MANN KI BAAT #Transformingindia Women officers commissioned in short service will get opportunity 2 for permanent commission like their male counterparts. The practise of Triple Talaq has caused great injustice among women. 3 I ensure the Muslim sister that I will work to ensure justice is done to them. If we had continued at the same pace at which toilets were being built 4 in 2013, the pace at which electrification was happening in 2013, then it would have taken us decades to complete them. The demand for MSP was pending for years. -

'Mann Ki Baat 2.0' on 30.08.2020

9/2/2020 Press Information Bureau Prime Minister's Office English rendering of PM’s address in the 15th Episode of ‘Mann Ki Baat 2.0’ on 30.08.2020 Posted On: 30 AUG 2020 11:33AM by PIB Delhi My dear countrymen, Namaskar. Generally, this period is full of festivals; fairs are held at various places; it’s the time for religious ceremonies too. During these times of Corona crises, on the one hand people are full of exaltation and enthusiasm too; and yet in a way there’s also a discipline that touches our heart. Broadly speaking in a way, there is a feeling of responsibility amongst citizens. People are getting along with their day to day tasks, while taking care of themselves and others as well. At every event being organised in the country, the kind of patience and simplicity being witnessed this time is unprecedented. Even Ganeshotsav is being celebrated online at certain places; at most places eco-friendly Ganesh idols have been installed. Friends, if we observe very minutely, one thing will certainly draw our attention- our festivals and the environment. There has always been a deep connect between the two. On the one hand, our festivals implicitly convey the message of co- existence with the environment and nature; on the other, many festivals are celebrated precisely for protecting nature. For example, in West Champaran district of Bihar, people belonging to Thaaru tribal community have been observing a sixty-hour lockdown for centuries…..in their own words- ‘Saath ghante ke Barna’. The Thaaru community has adopted BARNA as a tradition for protection of nature; that too for centuries. -

Topical Focus of Political Campaigns and Its Impact: Findings from Politicians’ Hashtag Use During the 2019 Indian Elections

Topical Focus of Political Campaigns and its Impact: Findings from Politicians’ Hashtag Use during the 2019 Indian Elections ANMOL PANDA, Microsoft Research India RAMARAVIND KOMMIYA MOTHILAL, Microsoft Research India MONOJIT CHOUDHURY, Microsoft Research India KALIKA BALI, Microsoft Research India JOYOJEET PAL, Microsoft Research India We studied the topical preferences of social media campaigns of India’s two main political parties by examining the tweets of 7382 politicians during the key phase of campaigning between Jan - May of 2019 in the run up to the 2019 general election. First, we compare the use of self-promotion and opponent attack, and their respective success online by categorizing 1208 most commonly used hashtags accordingly into the two categories. Second, we classify the tweets applying a qualitative typology to hashtags on the subjects of nationalism, corruption, religion and development. We find that the ruling BJP tended to promote itself over attacking the opposition whereas the main challenger INC was more likely to attack than promote itself. Moreover, while the INC gets more retweets on average, the BJP dominates Twitter’s trends by flooding the online space with large numbers of tweets. We consider the implications of our findings hold for political communication strategies in democracies across the world. CCS Concepts: • Human-centered computing → Social media; Collaborative content creation; Computer supported cooperative work; Social networking sites. Additional Key Words and Phrases: Twitter; India; Politics; Hashtags; Election Campaigns; Narendra Modi; Rahul Gandhi; Political Communication; Polarization ACM Reference Format: Anmol Panda, Ramaravind Kommiya Mothilal, Monojit Choudhury, Kalika Bali, and Joyojeet Pal. 2020. Topical Focus of Political Campaigns and its Impact: Findings from Politicians’ Hashtag Use during the 53 2019 Indian Elections. -

![Cryf] Vjvd D`Fey Gzr Hrjr RU](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6130/cryf-vjvd-d-fey-gzr-hrjr-ru-1866130.webp)

Cryf] Vjvd D`Fey Gzr Hrjr RU

<5- , * != & ! != = 2+*3&'2$04)5 % %& !"#$ ' (#) , ! 5;6. #$""9>56>,6? #"6%65 -6.;.# $">: %;>,.%;#%"6: " ;,# ;"-; "65:>$-.6 -9>56%%6@ . %%@33A#" -6;-#" ;@-6%-9@:- -&1322$ A B &6 # 0#6078 0)9 !" "6:-6.; he will never leave it. Reacting to the develop- he Congress on Sunday ment, CPI(M) Politburo mem- Tended weeks of speculation ber Prakash Karat said the about party president Rahul decision of the Congress to Gandhi contesting from two field Rahul from Wayanad seats in the Lok Sabha polls. It shows that the party wants to is now official: Rahul will be in take on the Left in Kerala. the fray from Wayanad in “Their priority now is to Kerala besides his traditional fight against the Left in Kerala. stronghold of Amethi in Uttar It goes against Congress’ Pradesh. national commitment to fight "6:-6.; Wayanad district is in the BJP, as in Kerala it’s LDF which north eastern part of Kerala is the main force fighting BJP n a free-wheeling interaction touching border with there,” he told reporters. The Iat a “Main bhi Chowkidar’ Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, CPI(M) ex-general secretary event, Prime Minister and houses various tribal said his party will work to Narendra Modi on Sunday groups of the latter. The area ensure the defeat of Rahul in attacked Congress dynasty, was badly affected in the last Wayanad. credibility of its “garibi hatao” " # $ % " O$ year’s floods. BJP chief Amit Shah too slogans, and discomfort of % $ While the Congress said it took a dig at Rahul. “Congress’ dynasty with his popularity. -

Reviving Public Service Broadcasting for Governance: a Case Study in India

NO. 2 VOL. 2/ JUNE 2017 http://dx.doi.org/10.222.99/arpap/2017.15 Reviving Public Service Broadcasting for Governance: A Case Study in India MEGHANA HR ABSTRACT Received: 12 March 2017 In the age of digitalization, radio and television are regarded as Accepted: 05 April 2017 Published: 14 June 2017 traditional media. With the popularity of internet, the traditional media are perceived as a passé. This stance stays Corresponding author: staunch to public broadcasting media. The public broadcasting Meghana HR media in India is witnessing a serious threat by the private sector Research Scholar Under the Guidance of Dr. ever since privatization policies were introduced way back in the H.K. Mariswamy Bangalore early 90s. The private radio stations and television channels are University, India consigned with an element of entertainment that the former Email: meghs.down2earth@gmail. public broadcasting media severely lacked. Doordarshan (DD) com and All India Radio (AIR) which is a part of the broadcasting media in India in the recent time are trying to regain its lost sheen through more engaging programmers. One such effort is the programme „Mann Ki Baat‟, an initiative by Prime Minister Narendra Modi. The programme aims at delivering the voice of Prime Minister to the public and also obtains the concerns of the masses. At a time when private television and radio stations have accomplished the mission of luring large audience in India, a government initiated programme – Mann Ki Baath has made a difference in repossessing the lost charm of public broadcasting media in India. This paper intends to explore the case study of „Mann Ki Baath‟ programme as a prolific initiative in generating revenue to public broadcasting media and also accenting the ideas of the government.