Mental Health Services During the First Wave of the COVID

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joineu-SEE Scholarship Scheme for Academic Exchange Between EU

Consortium members EU Universities • University of Graz, Austria – co-ordinator www.joineusee.eu • Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic • University of Bologna, Italy • University of Granada, Spain • University of Groningen, The Netherlands • University of Latvia, Riga, Latvia • University of Leuven, Belgium • University of Maribor, Slovenia • University of Turku, Finland • Vilnius University, Lithuania Western Balkan Universities • Ss. Cyril and Methodius University in Skopje, FYR of Macedonia • University of Belgrade, Serbia • University of Montenegro, Montenegro • University of Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina • University of Novi Sad, Serbia • University of Prishtina, Kosovo (as defined under UNSCR 1244/99) • University of Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina • University of Tirana, Albania • University of Tuzla, Bosnia and Herzegovina • University of Zadar, Croatia Associate partners Contact • Instituto per l’Europa Centro Orientale e University of Graz Balcanica, Forli, Italy International Relations Office • International Network of Albanian Student Universitaetsplatz 3 Associations, Tirana, Albania 8010 Graz, Austria JoinEU-SEE • know&how Junior Enterprise, Graz, Austria Scholarship scheme for • Kosova Academic Services, Prishtina, Kosovo (as [email protected] defined under UNSCR 1244/99) • World University Service – academic exchange between Austrian Committee, Graz, Austria Imprint: EU and Publisher: University of Graz, International Relations Office © 2010 Editorial: Sylvia Schweiger Western Balkan countries Design, Typesetting -

Telepsychiatry at the University of Virginia

An Overview of Telepsychiatry and the Experience at the University of Virginia August 2016 Anita Clayton, MD Chair Larry Merkel, MD, PhD; Department of Psychiatry What Do We Know About Telepsychiatry?* • It is given high marks for satisfaction by patients and rural practitioners, but less so by mental health professionals • It is as reliable as in-person as to clinical evaluation, diagnosis, and use of rating scales. • It is at least as effective as in-person treatment for depression and serious mental illness. • It may provide a higher level of care than in-person encounters. *References in accompanying manuscript UVA Telemedicine Partner Network University of Virginia Telemedicine Partner Sites Telehealth Education Sites Phases of Development • Phase I: 1998-2002 Individual Psychiatrists • Phase II: 2003-2007 Regularly Scheduled Service (2006 C&F Service begins) • Phase III: 2008-2011 PGY IV Elective • Phase IV: 2012-2016 Integrated into PGY III Training and use of APNPs, expansion to EDs Consultation Care Model • The local clinic identifies the cases • The patient is seen by us in consultation • We make recommendations • It is up to the local clinicians to act on these recommendations • They may contact us if there are problems or non-response • We may or may not see the patient again in follow-up as determined by the local clinician • Ad Hoc education and coordination Collaborative Care Model • A local clinician is identified as the contact person and oversees the mental health care (Behavioral Health Consultant) • They act as a bridge -

Eating Disorders Toolkit

NSW Eating Disorders Toolkit A PRACTICE-BASED GUIDE TO THE INPATIENT MANAGEMENT OF CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS WITH EATING DISORDERS NSW Ministry of Health 73 Miller Street NORTH SYDNEY NSW 2060 Tel. (02) 9391 9000 Fax. (02) 9391 9101 TTY. (02) 9391 9900 www.health.nsw.gov.au Produced by: NSW Ministry of Health This work is copyright. It may be reproduced in whole or in part for clinical use, study or training purposes subject to the inclusion of an acknowledgement of the source. It may not be reproduced for commercial usage or sale. Reproduction for purposes other than those indicated above requires written permission from the NSW Ministry of Health. © NSW Ministry of Health 2018 SHPN (MH) 170582 ISBN is 978-1-76000-743-0 Further copies of this document can be downloaded from the NSW Health webpage www.health.nsw.gov.au February 2018 ii NSW Health NSW Eating Disorders Toolkit Acknowledgements The Toolkit is a revision of the original Toolkit MH-CYP and CEDD would like to thank the whose development was facilitated by the former expert panel who assisted with the revision MH-Kids (now MH-Children and Young People) of this document: in conjunction with a variety of clinicians and academics throughout NSW, nationally and • Ms Danielle Maloney internationally. • Dr Sloane Madden • Ms Joanne Titterton This revision was facilitated by MH-Children and Young People (MH-CYP), of the Mental Health • Ms Mel Hart Branch, NSW Health and the Centre for Eating • Dr Julie Adamson and Dieting Disorders (CEDD), The Boden • Dr Michael Kohn Institute of Obesity, Nutrition, Exercise and Eating • Dr Rod McClymont Disorders, Sydney University. -

The COVID-19 Pandemic and Eating Disorders in Children, Adolescents

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Libraries & Cultural Resources Open Access Publications 2021-04-16 The COVID-19 pandemic and eating disorders in children, adolescents, and emerging adults: virtual care recommendations from the Canadian consensus panel during COVID-19 and beyond Couturier, Jennifer; Pellegrini, Danielle; Miller, Catherine; Bhatnagar, Neera; Boachie, Ahmed; Bourret, Kerry; Brouwers, Melissa; Coelho, Jennifer S; Dimitropoulos, Gina; Findlay, Sheri... Journal of Eating Disorders. 2021 Apr 16;9(1):46 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/113266 Journal Article Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca Couturier et al. Journal of Eating Disorders (2021) 9:46 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-021-00394-9 GUIDELINE Open Access The COVID-19 pandemic and eating disorders in children, adolescents, and emerging adults: virtual care recommendations from the Canadian consensus panel during COVID-19 and beyond Jennifer Couturier1,2* , Danielle Pellegrini1, Catherine Miller3, Neera Bhatnagar1, Ahmed Boachie4, Kerry Bourret5, Melissa Brouwers6, Jennifer S. Coelho7, Gina Dimitropoulos8, Sheri Findlay1,2, Catherine Ford9, Josie Geller7, Seena Grewal4, Joanne Gusella10, Leanna Isserlin6, Monique Jericho8, Natasha Johnson1,2, Debra K. Katzman4, Melissa Kimber1, Adele Lafrance11, Anick Leclerc2, Rachel Loewen12, Techiya Loewen13, Gail McVey4, Mark Norris6, David Pilon10, Wendy Preskow14, Wendy Spettigue6, Cathleen Steinegger4, Elizabeth Waite15 and Cheryl Webb1,2 Abstract Objective: The COVID-19 pandemic has -

Telepsychiatry: Overcoming Barriers to Implementation

Telepsychiatry: Overcoming barriers to implementation Providing treatment via videoconferencing can improve access to care lthough many states have substantial health services in urban areas, these services—particularly men- Atal health care—are relatively scarce in rural areas.1 Telepsychiatry, in which clinicians provide mental health care from a distance in real time by using interactive, 2-way, audio-video communication (videoconferencing), could mitigate workforce shortages that affect remote and un- derserved areas.2 Psychiatry is one of the biggest users of telemedicine, which refers to any combination of communi- cation technology and medicine.3-5 This article discusses tele- psychiatry’s effectiveness in providing psychiatric diagnosis and treatment, and the clinical implications of this technol- ogy, including improving access, cost, and quality of mental © OCEAN/CORBIS health services. Sy Atezaz Saeed, MD Professor and Chair Richard M. Bloch, PhD Outcomes comparable to face-to-face care Professor and Director of Research Telepsychiatry is used primarily in rural areas or correc- John M. Diamond, MD tional institutions or with underserved populations such Professor and Director as veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder or children. Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Although the literature generally is weak, there has been • • • • more research on psychiatry than other medical special- Department of Psychiatric Medicine ties because psychiatric clinicians rely on mental status Brody School of Medicine examinations and verbal communications, not physical East Carolina University Greenville, NC exams. Telepsychiatry can be considered a part of an evolv- ing “connected health” system that offers many benefits to patients and clinicians (see the Table at CurrentPsychiatry. com). -

APA Provides Testimony for House

Testimony of the American Psychiatric Association On April 28, 2021 Submitted for the record to the U.S. House of Representatives Ways and Means Committee In reference to the HELP SUBCOMMITTEE HEARING: Charting the Path Forward for Telehealth Chairman Doggett, Ranking Member Nunes, and distinguished members of the Health Subcommittee of the House Ways and Means Committee, thank you for the opportunity to submit testimony for the record on behalf of the over 37,400 psychiatrists of the American Psychiatric Association (APA) for your April 28, 2021 hearing entitled “Charting the Path Forward on Telehealth.” The APA is dedicated to providing our physician members with education and training on the most modern evidence-based treatments to diagnose and treat patients with mental illness and substance use disorders (SUD). The APA and our members are focused on ensuring humane care and effective treatment for all persons with mental illness and SUD and are actively engaged in pursuing policies that affect our patients’ access to quality care. In our statement, we want to highlight data and policies related to the access of mental health and SUD care via telepsychiatry. During the COVID-19 pandemic, swift actions by Congress and the Administration have allowed many of our psychiatrists to transition from seeing most patients in person to delivering much of their psychiatric care via telepsychiatry. We have both Congress and the current and previous Administrations to thank for the lifting of geographic and site of service restrictions, including allowing patients to be seen in their homes, and allowing the use of clinically appropriate audio-only for telehealth when a patient lacks the technology, ability or the bandwidth for video. -

New Technologies for Improving Behavioral Health

ISSUE BRIEF New Technologies for Improving Behavioral Health A National Call for Accelerating the Use of New Methods for Assessing and Treating Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders Prepared by: Adam Powell, PhD along with The Kennedy Forum senior leadership team, including Patrick J. Kennedy, and Garry Carneal, JD, Steve Daviss, MD and Henry Harbin, MD. Kennedy Forum Focus Group Participants:* Ŋ Patrick J. Kennedy Ŋ Jocelyn Faubert, PhD Ŋ Sharon Kilcarr Ŋ Steve Ronik, PhD The Kennedy Forum Université de Montréal HealthTrackRx Henderson Behavioral Health Ŋ Alicia Aebersold Ŋ Majid Fotuhi, MD, PhD Ŋ Mike Knable, DO, DFAPA Ŋ Linda Rosenberg National Council for Behavioral NeuroGrow Brain Fitness Center Sylvan C. Herman Foundation National Council for Community Health Behavioral Health Ŋ Don Fowls, MD Ŋ Allison Kumar Ŋ Ŋ Alan Axelson, MD Don Fowls and Associates FDA/CDRH Kevin Scalia InterCare Health Systems Limited Netsmart Ŋ Shanti Fry Ŋ Corinna Lathan, PhD, PE Ŋ Ŋ Bill Bucher Neuromodulation Working Group AnthroTronix, Inc. Michael Schoenbaum, PhD LabCorp National Institute of Mental Health Ŋ Adam Gazzaley, MD, PhD Ŋ David Lischner, MD Ŋ Ŋ Michael Byer Neuroscience Imaging Center Valant Steve Sidel M3 Information Mindoula Ŋ Robert Gibbons Ŋ Jay Lombard, DO Ŋ Ŋ John H. Cammack University of Chicago GenoMind Kate Sullivan, MS, CCC-SLP, Cammack Associates, LLC CBIS Ŋ Robert Gibbs Ŋ Zack Lynch Walter Reed National Military Medical Center Ŋ Garry Carneal, JD, MA Genomind Neurotechnology Industry Organization The Kennedy Forum Ŋ Ŋ Evian -

Advancing Gender Equality at SAGE Universities: International University of Sarajevo

Advancing gender equality at SAGE universities: International University of Sarajevo. September 2018 – February 2019 International University of Sarajevo received a grant as part of project Horizon 2020 from Council of Ministers of BiH for 2017-2018. Namely, Horizon 2020 “Gender Equality in Higher Education” plan which was being implemented at the International University of Sarajevo (IUS) is first of its kind in this region. Project coordinator Dr Jasminka Hasić Telalović decided to present this plan at other, public universities in Bosnia and Herzegovina by applying to the Council of Ministers grant. The grant would allow IUS to position itself as leader in implementation of gender equality policies in higher education area, through workshops and lectures. IUS SAGE Team organized meetings with representatives of public universities in Bosnia and Herzegovina, which were included: University of East Sarajevo, University of Mostar, University of Banja Luka, University of Zenica, University of Tuzla, “Džemal Bijedić” University in Mostar and University of Sarajevo. IUS SAGE Team was host of the workshop, where 13 universities’ participants were met with facts of introducing systemic actions for gender equality in higher education, and how it could be helpful for the quality of education. Workshop was mentored by expertise: Dr Jasminka Hasic Telalovic, who presented creation and implementation process of Gender Equality Plan at IUS. Prof Eileen Drew, coming from Trinity College Dublin, who is SAGE project Coordinator and Prof Yvonne Galligan, Queens University Belfast, presented their experiences as the leaders of gender equality in higher education in United Kingdom and Ireland. Professor Eileen Drew lectured about: Turning Gender GAPs into Gender Equality Plans (GEPs): Lessons from Trinity College Dublin. -

Pediatric Telepsychiatry Curriculum for Graduate Medical Education

Pediatric Telepsychiatry Curriculum Graduate Medical Education (GME) and Continuing Medical Education (CME) May 2020 AUTHORS Sandra M. DeJong, MD, MSc Cambridge Health Alliance/Harvard Medical School 1493 Cambridge Street, Cambridge MA 02139 [email protected] Members of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) Telepsychiatry Committee: Dan Alicata, MD Debbie Brooks, MD Shabana Khan, MD – Co -Chair Kathleen Myers, MD David Pruitt, MD – Co-Chair Ujjwal Ramtekkar, MD David Roth, MD Lan Chi ”Krysti” Vo, MD Additional Contributors: Bianca Busch, MD 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Topic Page 2 Table of Contents…………………………………………. 3 3 Introduction………………………………………………… 4 4 Curriculum Overview……………………………….…….. 8 5 Goals and Objectives……………………………….……. 10 6 Curriculum Outline…………………………………..……. 16 7 Curriculum Guide…………………………………………. 23 8 Evaluation Tools…………………………………………… 33 9 Evaluation and Dissemination of Curriculum……… 69 10 Acknowledgements………………………………………. 70 11 References…………………………………………………. 71 12 Appendix………………………………………………… 75 3 Section 3 INTRODUCTION This curriculum was developed using Kern’s 6-stage model of curriculum development. KERN’S 6-STAGE MODEL OF CURRICULUM DEVELOPMENT 1. Identification of the core need/problem and general needs assessment 2. Targeted needs assessment 3. Development of broad goals and measurable specific objectives 4. Development of educational content and method 5. Implementation 6. Evaluation and feedback at the level of the individual learner and the program Thomas, et al. 2016 PROBLEM IDENTIFICATION AND NEEDS ASSESSMENT The United States currently faces a dire shortage of child/adolescent psychiatrists (CAPs). While the estimated need is 30,000, only 8,000 CAPs are in practice nationally, and their mean age is 53 years. Most counties in the United States (US) have no CAPs, and the average wait time to see a CAP is 7.5 weeks (AACAP 2018). -

Chemistry Education in Bosnia and Herzegovina

c e p s Journal | Vol.10 | No1 | Year 2020 83 doi: 10.26529/cepsj.715 Chemistry Education in Bosnia and Herzegovina Meliha Zejnilagić-Hajrić*1 and Ines Nuić2 • In this paper, the education system in Bosnia and Herzegovina is pre- sented in the light of current state-level legislation, with an emphasis on chemistry education at the primary, secondary and tertiary level. The consequences of the last war in our country still persist and are visible in many aspects of everyday life, including the education system, thus lim- iting the efforts of education professionals to follow international trends in education. There are three valid curricula for primary education at the national level, each of which differs in the national group of school subjects. Teaching methods are common for all three curricula and are mainly teacher-oriented. The situation is similar with regard to second- ary education. Study programmes at the university level are organised in accordance with the Bologna principles. The programmes are made by the universities themselves and approved by the corresponding ministry of education. Chemical education research in Bosnia and Herzegovina is mainly conducted at the University of Sarajevo. It deals with (1) the problems of experimental work in chemistry teaching, resulting in more than 60 experiments optimised for primary and secondary school, (2) integrating the knowledge of chemistry, physics and physical chemis- try for university students, with regard to students’ difficulties observed during university courses and potential solutions, and (3) the effective- ness of web-based learning material in primary school chemistry for the integration of macroscopic and submicroscopic levels. -

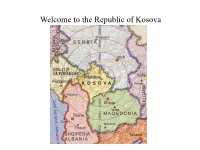

UNIVERSITY of PRISHTINA the University-History

Welcome to the Republic of Kosova UNIVERSITY OF PRISHTINA The University-History • The University of Prishtina was founded by the Law on the Foundation of the University of Prishtina, which was passed by the Assembly of the Socialist Province of Kosova on 18 November 1969. • The foundation of the University of Prishtina was a historical event for Kosova’s population, and especially for the Albanian nation. The Foundation Assembly of the University of Prishtina was held on 13 February 1970. • Two days later, on 15 February 1970 the Ceremonial Meeting of the Assembly was held in which the 15 February was proclaimed The Day of the University of Prishtina. • The University of Prishtina (UP), similar to other universities in the world, conveys unique responsibilities in professional training and research guidance, which are determinant for the development of the industry and trade, infra-structure, and society. • UP has started in 2001 the reforming of all academic levels in accordance with the Bologna Declaration, aiming the integration into the European Higher Education System. Facts and Figures 17 Faculties Bachelor studies – 38533 students Master studies – 10047 students PhD studies – 152 students ____________________________ Total number of students: 48732 Total number of academic staff: 1021 Visiting professors: 885 Total number of teaching assistants: 396 Administrative staff: 399 Goals • Internationalization • Integration of Kosova HE in EU • Harmonization of study programmes of the Bologna Process • Full implementation of ECTS • Participation -

Reviewer Acknowledgements

Journal of Politics and Law; Vol. 13, No. 2; 2020 ISSN 1913-9047 E-ISSN 1913-9055 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Reviewer Acknowledgements Journal of Politics and Law wishes to acknowledge the following individuals for their assistance with peer review of manuscripts for this issue. Their help and contributions in maintaining the quality of the journal are greatly appreciated. Journal of Politics and Law is recruiting reviewers for the journal. If you are interested in becoming a reviewer, we welcome you to join us. Please contact us for the application form at: [email protected] Reviewers for Volume 13, Number 2 Ali Qtaishat, Al-Imam Muhammed Ibn Saud Islamic University, Saudi Arabia Ana Rodica Stăiculescu, “OVIDIUS” University of Constanta, Romania Arusyak Hovhannisyan, RUDN, Russia Daniel Lena Marchiori Neto, Catholic University of Pelotas, Brazil David Schultz, Hamline University, USA Davor Trlin, International Burch University Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina Diogo Monteiro Dario, University of St Andrews, Brazil Drozdova Alexandera, North-Caucasian Federal University, Russia Elisa D’Alterio, University of Catania, Italy Emmanouela Mylonaki, London South Bank University, UK Fábio Albergaria de Queiroz, Brazilian War College, Brazil Farouq Shibli, Philadelphia University, Jordan Gnatovskaya Elena, Primorye State Agricultural Academy, Russia Hasmi Rusli Mamychev, University of Sains Islam Malasya, Malaysia Ibrahim El Hussari, Lebanese American University, Lebanon Ida Madieha Azmi, International Islamic University