Estimates of the Cost of Capital Relevant for Investment Decisions Under Uncertainty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Impact of Relevant Costing for Decision-Making in Ready- Made Garments (Rmgs) Industry of Bangladesh

IOSR Journal of Business and Management (IOSR-JBM) e-ISSN: 2278-487X, p-ISSN: 2319-7668. Volume 16, Issue 3. Ver. I (Mar. 2014), PP 01-07 www.iosrjournals.org The Impact of Relevant Costing for decision-making in Ready- Made Garments (RMGs) industry of Bangladesh. , 1(Department of Accounting, Hajee Mohammad Danesh Science and Technology University, Bangladesh. 2(Lecturer, Department of Accounting, Hajee Mohammad Danesh Science and Technology University, Bangladesh. Abstract: Relevant costing is a management accounting term that relates to focus on only the cost relevant to a specific decision being made. Irrelevant costs are excluded from any incremental decision-making problem because they are supposed to have equal effects on all the available alternatives ( Dillon, R. D. and, J. F. Nash, 1978). This study adopts an observation of quantitative method with primary and secondary data in view of the nature of the analysis. Relevant costing is often used in short-term decision-making and a number of specific practical examples are illustrated in this study. This study has designed to make the aim of assessing the level of perceptions of four areas such as (i) making and buying; (ii) dropping or retaining a segment; (iii) constrained resources; and (iv) special orders; in using relevant costing in Ready-Made Garments (RMGs) industry of Bangladesh. To meet this aim total 100 companies as a sample from Ready-Made Garments (RMGs) industry have been randomly selected. By using variance analysis, authors have found that all four factors have significant influence in using relevant costing. Last, the result of this study suggested that the strengthening the decision-making mechanism required a strong relevant costing benefits and its proper application. -

9.1 Financial Cost Compared with Economic Cost 9.2 How

9.0 MEASUREMENT OF COSTS IN CONSERVATION 9.1 Financial Cost Compared with Economic Cost{l} Since financial analysis relates primarily to enterprises operating in the market place, the data of costs and retums are derived from the market prices ( current or expected) of the transactions as they are experienced. Thus the cost of land, capital, construction, etc. is the ~ recorded price of the accountant. By contrast, in economic analysis ( such as cost bene fit analysis) the costs and benefits of a project are analysed from the point of view of society and not from the point of view of a single agent's utility of the landowner or developer. They are termed economic. Some effects of the project, though conceming the single agent, do not affect society. Interest on borrowing, taxes, direct or indirect subsidies are transfers that do not deploy real resources and do not therefore constitute an economic cost. The costs and the retums are, in part at least, based on shadow prices, which reflect their "social value". Economic rate of retum could therefore differ from the financial costs which are based on the concept of "opportunity cost"; they are measured not in relation to the transaction itself but to the value of the resources which that financial cost could command, just as benefits are valued by the resource costs required to achieve them. This differentiation leads to the following significant rules in conside ring costs in cost benefit analysis, as for example: (a) Interest on money invested This is a transfer cost between borrower and lender so that the economyas a whole is no different as a result. -

RECENT STIMULUS PACKAGES and WTO LAW on SUBSIDIES Santiago Ibáñez Marsilla

World Customs Journal RECENT STIMULUS PACKAGES AND WTO LAW ON SUBSIDIES Santiago Ibáñez Marsilla Abstract Major world economies are simultaneously experiencing deep recession due to the world economic crisis, and in attempting to contain the extent of damage, governments have been introducing unprecedented stimulus packages. These stimulus programs raise many concerns from the perspective of international trade rules. This paper analyses those concerns in relation to possible conflicts with the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (ASCM). The concept of ‘subsidy’ in WTO law is discussed, together with the analysis of two salient measures, export credit support and the automobile industry, that are currently being adopted in response to the current crisis. A further critical analysis is provided on recent developments in the review of the ASCM as part of the Doha Round. 1. Introduction Amid the current economic crisis, that has thrown the major world economies into a simultaneous deep recession, governments are struggling to contain the extent of the damage. Due to the apparent failure of past economic policies that encouraged minimum State intervention and regulation of the markets, previously regarded as ‘heterodox’ economic policies are the order of the day and, as a result, unprecedented stimulus packages have been unleashed.1 These stimulus programs raise many concerns from the perspective of international trade rules. In this paper we will analyse possible conflicts with the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (ASCM). The relevance of this issue is highlighted by the fact that, in the context of the present financial and economic crisis, subsidies in developed countries have so far been the measure causing most concern for the international trade regime.2 In Section 2, we elaborate the concept of subsidy in WTO law3 and establish the elements for an analysis of different measures adopted in response to the current crisis, which is presented in Section 3. -

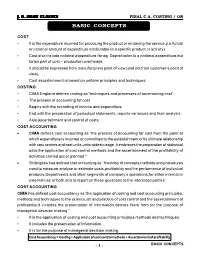

CHAPTER 1.Pmd

JJJ... K. SHAH CLASSES FINAL C.A. COSTING / OR BASIC CONCEPTS COST • It is the expenditure incurred for producing the product or rendering the service.(i.e Actual or notional amount of expenditure attributable to a specific product or activity) • Cost also include notional expenditure.for eg. Depreciation is a notional expenditure but forms part of cost – production overheads. • It should be expressed from manufacturers point of view (and not from customer’s point of view). • Cost ascertainment is based on uniform principles and techniques COSTING • CIMA England defines costing as “techniques and processes of ascertaining cost”. • The process of accounting for cost • Begins with the recording of income and expenditure • End with the preparation of periodical statements, reports variances and their analysis. • Aids ascertainment and control of costs. COST ACCOUNTING • CIMA defines cost accounting as “the process of accounting for cost from the point at which expenditure is incurred or committed to the establishment of its ultimate relationship with cost centres and cost units.units widest usage ,it embraces the preparation of statistical data,the application of cost control methods and the ascertainment of the profitability of activities carried out or planned.” • Shilling law has defined cost accounting as “ the body of concepts,methods and procedures used to measure,analyse or estimate costs,profitability and the performance of individual products.Departments and other segments of company’s operations,for either internal or external use -

WTO Documents Online

WORLD TRADE TN/RL/W/146 11 March 2004 ORGANIZATION (04-1067) Negotiating Group on Rules Original: English PROPOSAL ON ISSUES RELATED TO AFFILIATED PARTIES Paper from Brazil; Colombia; Costa Rica; Hong Kong, China; Japan; Korea; Norway; Singapore; Switzerland; the Separate Customs Territory of Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen and Matsu; and Thailand This proposal concerns the issues related to affiliated parties. These issues have been identified in document TN/RL/W/10. Other Members have also referred to this issue in documents TN/RL/W/66, TN/RL/W/81, TN/RL/W/86 and TN/RL/W/130. This proposal indicates one way to overcome and resolve the problems resulting from the lack of clear definitions of affiliated parties and the problems resulting from the absence of rules in the treatment of affiliated transactions. The discussions in the Negotiating Group may assist in improving this proposal. Consequently, we reserve our right to modify or complement the proposal as appropriate. In preparing and/or analyzing specific provisions, it is clear that amendment of the existing text may have an impact on other Articles of the AD Agreement, which have so far not been explicitly addressed. These links cannot be fully addressed until we have seen a comprehensive overview of proposed amendments. Consequently, we also reserve the right to make proposals on provisions which may not have been explicitly addressed so far for clarification or improvement. Issues: Definition of “Affiliated Party” Transactions and Their Relevance in Determining Normal Value and Constructed Export Price; “Collapsing” of Multiple Entities. Relevant Provisions: Articles 2.2 and 2.3. -

Getting Down to Business: Making the Most of the WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement

GETTING DOWN TO BUSINESS MAKING THE MOST OF THE WTO TRADE FACILITATION AGREEMENT In partnership with: Getting Down to Business Making the Most of the WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement Getting Down to Business: Making the Most of the WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement About the paper Implementing the World Trade Organization’s Trade Facilitation Agreement is a unique opportunity for developing countries and least developed countries to simplify and modernize their trade and border procedures. This report assists policymakers and traders to understand the benefits, legal obligations and key factors for successful implementation of each measure in the Agreement. It provides technical notes and guidelines for step-by-step national implementation plans and checklists to ensure compliance for each measure. Publisher: International Trade Centre Title: Getting down to business: Making the Most of the WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement Publication date and place: Geneva, May 2020 Page count: 150 Language: English ITC Document Number: TFBP-19-129.E Citation: International Trade Centre (2020). Getting down to business: Making the Most of the WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement. ITC, Geneva. For more information, contact: Mohammad Saeed, [email protected] ITC encourages the reprinting and translation of its publications to achieve wider dissemination. Short extracts of this paper may be freely reproduced, with due acknowledgement of the source. Permission should be requested for more extensive reproduction or translation. A copy of the reprinted or translated material should be sent to ITC. Digital image(s) on the cover: © Shutterstock © International Trade Centre (ITC) ITC is the joint agency of the World Trade Organization and the United Nations. -

Cost Behaviour

1 Cost Behaviour Cost Behaviour 1 Concepts and definitions questions 1.1 Distinguish between (i) Financial accounting (ii) Cost accounting (iii) Management accounting 1.2 State six different benefits of cost accounting. (i) (ii) (iii) (iv) (v) (vi) 1.3 Complete the following statements. (i) A __________ is a unit of product or service in relation to which costs are ascertained. (ii) A __________ cost is an expenditure which can be economically identified with and specifically measured in respect to a relevant cost object. (iii) __________ cost is the total cost of direct material, direct labour and direct expenses. (iv) An __________ or __________ cost is an expenditure on labour, materials or services which cannot be economically identified with a specific saleable cost unit. (v) A cost __________ is a production or service location, function, activity or item of equipment for which costs are accumulated. (vi) A __________ cost is a cost which is incurred for an accounting period and which tends to be unaffected by fluctuations in the levels of activity. (vii) A __________ cost is a cost which changes in total in relation to the level of output. (viii) An example of a fixed cost is __________. (ix) An example of a variable cost is __________. (x) An example of a semi-fixed/semi-variable cost is __________. 3 4 Exam Practice Kit: Fundamentals of Management Accounting 1.4 The relationship between total costs Y and activity X is in the form: Y ϭ a ϩ bX a ϭ b ϭ 1.5 Use the high–low method to calculate the fixed and variable elements of the following costs. -

Identify Relevant and Irrelevant Costs and Benefits in a Decision. 10-2 Relevant Costs and Benefits

10-1 Learning Objective Identify relevant and irrelevant costs and benefits in a decision. 10-2 Relevant Costs and Benefits A relevant cost is a cost that differs between alternatives. A relevant benefit is a benefit that differs between alternatives. 10-3 Identifying Relevant Costs An avoidable cost is a cost that can be eliminated, in whole or in part, by choosing one alternative over another. Avoidable costs are relevant costs. Unavoidable costs are irrelevant costs. Two broad categories of costs are never relevant in any decision. They include: Sunk costs. A future cost that does not differ between the alternatives. 10-4 Keys to Successful Decision-Making 1. Focus only on relevant costs (also called avoidable costs, differential costs, or incremental costs) and relevant benefits (also called differential benefits or incremental benefits). 2. Ignore everything else including sunk costs and future costs and benefits that do not differ between the alternatives. 10-5 Different Costs for Different Purposes Costs that are relevant in one decision situation may not be relevant in another context. Thus, in each decision situation, the manager must examine the data at hand and isolate the relevant costs. 10-6 Identifying Relevant Costs Cynthia, a Boston student, is considering visiting her friend in New York. She can drive or take the train. By car, it is 230 miles to her friend’s apartment. She is trying to decide which alternative is less expensive and has gathered the following information. Automobile Costs (based on 10,000 miles driven -

C01-Fundamentals of Management Accounting

C01-Fundamentals of management accounting Sample Exam Paper (with detailed answers) Question 1 Which of the following words DOES NOT describe a main focus of management accounting? A. Planning B. Control C. External D. Decision-making C-External; Management accounting focuses on the business needs, therefore you should decide what management accounting is and eliminate that most obvious. Question 2 CIMA defines management accounting as: “The application of the principles of accounting and financial management to create, protect, preserve and increase value for the _________________ of for-profit and not-for profit enterprises in the public and private sectors”. A. Auditors B. Stakeholders C. Owners D. Customers B-Stakeholders; These can include shareholders, customers, suppliers, employees or anyone that could be affected by the company internally or externally. For a more detailed explanation of management accountants please visit the website. Question 3 Which of the following statements are true? 1. The main role of the management accountant is to produce financial accounts 2. Management accountants always work within the finance function 3. Management accountants always work in partnership with business managers A. 1 and 2 only B. 2 and 3 only C. 1 and 3 only D. None of the above D-None of the above; Management accountants can work in a variety of roles and also across a range of departments. To find out more about what CIMA students and members do please visit their profiles on the global website. Updated: Aug 2013 1 C01-Fundamentals of management accounting Question 4 Which of the following words complete the statement below? ____________ accounts are prepared for external stakeholders. -

Investment Facilitation and Mode 3 Trade in Services: Are Current Discussions Addressing the Key Issues?

Policy Research Working Paper 9229 Public Disclosure Authorized Investment Facilitation and Mode 3 Trade in Services Public Disclosure Authorized Are Current Discussions Addressing the Key Issues? Roberto Echandi Pierre Sauvé Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Macroeconomics, Trade and Investment Global Practice May 2020 Policy Research Working Paper 9229 Abstract Based on a novel approach to measuring the cost of trade in internationally. The paper explores the policy opportunity services for Modes 1 (cross-border supply), 2 (consumption costs arising from the decision to focus the investment facil- abroad), and 4 (temporary movement of service suppliers), itation agenda on matters of regulatory transparency and developed by the World Trade Organization Secretariat, this the streamlining of administrative procedures. It recalls how pper reviews available evidence on factors affecting trade reducing regulatory heterogeneity, tackling discriminatory costs for services supplied via a commercial presence in impediments to cross-border investment, and developing a host country market, so-called Mode 3 trade. It does investor-state conflict management mechanisms to retain so with a view to answering the question of whether the and expand investment and prevent dispute escalation— current “facilitation” agendas on services and investment all issues left unaddressed by ongoing negotiations—hold proceeding at the World Trade Organization focus on the important potential for reducing Mode 3 trade costs and most important factors affecting Mode 3–related trade costs, facilitating expanded investment. by far the most important of all modes of supplying services This paper is a product of the Macroeconomics, Trade and Investment Global Practice. It is part of a larger effort by the World Bank to provide open access to its research and make a contribution to development policy discussions around the world. -

Module 13 : Relevant Costs in Decision Making Lecture 1

Module 13 : Relevant Costs in Decision Making Lecture 1 : Relevant Costs in Decision Making Objectives In this lecture you will learn the following Decision Making Introduction. Relevant Vs. Sunk cost. Make or Buy decision making. Shutdown Cost. Joint Product. Joint Product Cost Allocation. Introduction of new product. Relevant Cost Cost which are relevant for a particular business decision. They are not historical cost but future costs to be associated with different inputs and activities related a particular business decision. Relevant cost is expected future cost which differs for alternative course. Usually variable costs are relevant while fixed cost are non-relevant. Ex. Make or Buy, Special Pricing. However, It is not essential that all variable cost are relevant and all fixed cost are irrelevant. Fixed or variable costs that differ for various alternatives are relevant costs. Relevant costs draw our alternation to those elements of cost which are relevant for decision. e.g. 1) Fixed Cost for project X is Rs. 5 lakhs and for alternative project Y it is 7 lakhs. therefore fixed cost is relevant in this example. E.g. 2) Direct material under alternative I- Rs. 150 per Kg. Direct material under alternative II- Rs. 150 per Kg. therefore variable cost is not relevant in this example. SUNK COSTS Sunk costs are all costs incurred or committed in the past that cannot be changed by any decision made now or in the future. Sunk costs should not be considered in decisions. E.g. cost incurred on research of a product will be irrelevant while making decision whether to undertake production or not. -

UNIT 8 COST CONCEPTS and ANALYSIS I Objectives After Going Through This Unit, You Should Be Able To

UNIT 8 COST CONCEPTS AND ANALYSIS I Objectives After going through this unit, you should be able to: understand some of the cost concepts that are frequently used in the managerial decision making process; differentiate between different cost concepts; distinguish between economic costs and accounting costs. Structure 8.1 Introduction 8.2 Actual Costs and Opportunity Costs 8.3 Explicit and Implicit Costs 8.4 Accounting Costs and Economic Costs 8.5 Direct Costs and Indirect Costs 8.6 Total Cost, Average Cost and Marginal Cost 8.7 Fixed and Variable Costs 8.8 Short-Run and Long-Run Costs 8.9 Summary 8.10 Self-Assessment Questions 8.11 Further Readings 8.1 INTRODUCTION The analysis of cost is important in the study of managerial economics because it provides a basis for two important decisions made by managers: (a) whether to produce or not and (b) how much to produce when a decision is taken to produce. In this Unit, we shall discuss some important cost concepts that are relevant for managerial decisions. We analyse the basic differences between these cost concepts and also, examine how accountants and economists differ on treating different cost concepts. We will continue the discussion on cost concepts and analysis in Unit 9. 8.2 ACTUAL COSTS AND OPPORTUNITY COSTS Actual costs are those costs, which a firm incurs while producing or acquiring a good or service like raw materials, labour, rent, etc. Suppose, we pay Rs. 150 per day to a worker whom we employ for 10 days, then the cost of labour is Rs.