Canal and Salt Town Middlewich, Cheshire Heritage Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meeting of the Parish Council

Clerk: Carol Jones Tel: 01270 262636 Email: [email protected] Web: www.shavingtononline.co.uk Parish Councillors are summoned to a MEETING OF THE PARISH COUNCIL DAY/DATE: WEDNESDAY, 3 FEBRUARY 2021 TIME: 7.30 PM MEETING TO BE HELD REMOTELY, VIA VIDEO-LINK PLATFORM: ZOOM ACCESS: Please click the link below. https://us02web.zoom.us/webinar/register/WN_DLGbiCxIRwSKhQNwGWUXYQ Enquiries to: Clerk: Carol Jones Issue date: 29 January 2021 Phone: 01270 262636 Signed: C M Jones To: Members of the Parish Council Councillors V Adams, L Buchanan, N Cooper, B Gibbs (Chairman), K Gibbs, J Hassall, M Ferguson, R Hancock, G McIntyre and R Moore Notes for Members of the Public: a) This meeting is being held remotely in accordance with regulations made under S.78 of the Coronavirus Act 2020. There are, therefore, no paper copies of the agenda or the accompanying documents. b) All documents (other than those which are restricted) can be accessed from the Parish Council’s website - www.shavingtononline.co.uk. c) If you wish to observe the meeting or make a statement under the Public Question Time slot, please ensure that you register using the link above. The system can accommodate a maximum of 100 attendees. Therefore, registration will be on a ‘first come, first served’ basis. Shavington-cum-Gresty Parish Council Agenda – (Meeting – 3 February 2021) A G E N D A 1 APOLOGIES 2 DECLARATION OF INTERESTS Members to declare any (a) disclosable pecuniary interest; (b) personal interest; or (c) prejudicial interest which they have in any item of business on the agenda, the nature of that interest, and in respect of disclosable interests and prejudicial interests, to withdraw from the meeting prior to the discussion of that item. -

Roadside Hedge and Tree Maintenance Programme

Roadside hedge and tree maintenance programme The programme for Cheshire East Higways’ hedge cutting in 2013/14 is shown below. It is due to commence in mid-October and scheduled for approximately 4 weeks. Two teams operating at the same time will cover the 30km and 162 sites Team 1 Team 2 Congleton LAP Knutsford LAP Crewe LAP Wilmslow LAP Nantwich LAP Poynton LAP Macclesfield LAP within the Cheshire East area in the following order:- LAP = Local Area Partnership. A map can be viewed: http://www.cheshireeast.gov.uk/PDF/laps-wards-a3[2].pdf The 2013 Hedge Inventory is as follows: 1 2013 HEDGE INVENTORY CHESHIRE EAST HIGHWAYS LAP 2 Peel Lne/Peel drive rhs of jct. Astbury Congleton 3 Alexandra Rd./Booth Lane Middlewich each side link FW Congleton 4 Astbury St./Banky Fields P.R.W Congleton Congleton 5 Audley Rd./Barley Croft Alsager between 81/83 Congleton 6 Bradwall Rd./Twemlow Avenue Sandbach link FW Congleton 7 Centurian Way Verges Middlewich Congleton 8 Chatsworth Dr. (Springfield Dr.) Congleton Congleton 9 Clayton By-Pass from River Dane to Barn Rd RA Congleton Congleton Clayton By-Pass From Barn Rd RA to traffic lights Rood Hill 10 Congleton Congleton 11 Clayton By-Pass from Barn Rd RA to traffic lights Rood Hill on Congleton Tescos side 12 Cockshuts from Silver St/Canal St towards St Peters Congleton Congleton Cookesmere Lane Sandbach 375199,361652 Swallow Dv to 13 Congleton Dove Cl 14 Coronation Crescent/Mill Hill Lane Sandbach link path Congleton 15 Dale Place on lhs travelling down 386982,362894 Congleton Congleton Dane Close/Cranberry Moss between 20 & 34 link path 16 Congleton Congleton 17 Edinburgh Rd. -

A Walk from Church Minshull

A Walk to Church Minshull Aqueduct Marina photo courtesy of Bernie Stafford Aqueduct Marina, the starting point for this walk, was opened in February 2009. The marina has 147 berths, a shop and a café set in beautiful Cheshire countryside. With comprehensive facilities for moorers, visiting boaters and anyone needing to do, or have done, any work on their boat, the marina is an excellent starting point for exploring the Cheshire canal system. Starting and finishing at Church Minshull Aqueduct Marina, this walk takes in some of the prettiest local countryside as well as the picturesque village of Church Minshull and the Middlewich Branch of the Shropshire Union Canal. Some alternative routes are also included at the end to add variation to the walk which is about five or six miles, depending on the exact route taken. Built to join the Trent and Mersey Canal with the Chester Canal, the Middlewich Branch carried mainly coal, salt and goods to and from the potteries. Built quite late in the canal building era, like so many other canals, this canal wasn’t as successful as predicted. Today, however, it is a very busy canal providing an essential link between the Trent and Mersey Canal at Middlewich and the Llangollen Canal as well as being part of the Four Counties Ring and linking to the popular Cheshire Ring boating route. The Route Leaving the marina, walk to the end of the drive and turn north (right) onto the B5074 Church Minshull road and walk to the canal bridge. Cross the canal and turn down the steps on the right onto the towpath, then walk back under the bridge, with the canal on your left. -

Holmes Chapel Settlement Report

Cheshire East Local Plan Site Allocations and Development Policies Document Holmes Chapel Settlement Report [ED 33] August 2020 OFFICIAL Contents 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................... 1 2. Holmes Chapel .................................................................................................... 2 Introduction .................................................................................................... 2 Neighbourhood Development Plan ................................................................ 2 Strategy for development in Holmes Chapel ................................................. 2 3. Development needs at Homes Chapel ................................................................ 4 4. Site selection ....................................................................................................... 5 Introduction .................................................................................................... 5 Stage 1: Establishing a pool of sites for Holmes Chapel ............................... 5 Stage 2: First site sift ..................................................................................... 5 Stage 3: Decision point – the need for sites in Holmes Chapel ..................... 6 Stage 4: Site assessment, Sustainability Appraisal and Habitats Regulations Assessment ................................................................................................... 6 Stages 5 to 7: Evaluation and initial recommendations; -

Middlewich Before the Romans

MIDDLEWICH BEFORE THE ROMANS During the last few Centuries BC, the Middlewich area was within the northern territories of the Cornovii. The Cornovii were a Celtic tribe and their territories were extensive: they included Cheshire and Shropshire, the easternmost fringes of Flintshire and Denbighshire and parts of Staffordshire and Worcestershire. They were surrounded by the territories of other similar tribal peoples: to the North was the great tribal federation of the Brigantes, the Deceangli in North Wales, the Ordovices in Gwynedd, the Corieltauvi in Warwickshire and Leicestershire and the Dobunni to the South. We think of them as a single tribe but it is probable that they were under the control of a paramount Chieftain, who may have resided in or near the great hill‐fort of the Wrekin, near Shrewsbury. The minor Clans would have been dominated by a number of minor Chieftains in a loosely‐knit federation. There is evidence for Late Iron Age, pre‐Roman, occupation at Middlewich. This consists of traces of round‐ houses in the King Street area, occasional finds of such things as sword scabbard‐fittings, earthenware salt‐ containers and coins. Taken together with the paleo‐environmental data, which hint strongly at forest‐clearance and agriculture, it is possible to use this evidence to create a picture of Middlewich in the last hundred years or so before the Romans arrived. We may surmise that two things gave the locality importance; the salt brine‐springs and the crossing‐points on the Dane and Croco rivers. The brine was exploited in the general area of King Street, and some of this important commodity was traded far a‐field. -

Buttermaking on the Farm

O F E S O D AIR" CHIEF F IC R F THE AND COLD STORAGE ' mm s n . A UDDICK s J . R Co i io er . , ' ’ v r r . J N L N hi f o f i rke t n d . I EI O C e D s D a "a s a l Sto . S G C . , i i ion y o d age F - v o f a P . Chief , Di isi n o D iry roduce C v s n r R esea rc h hief , Di i io of Dai y En fo rc em en t In Charge , of Dairy La ws . I C . n harge , Milk Utilization Service S n r a r P u e ra d H H C G . OS J . I e io D i y rod c er T . PRINC IP AL SERVICES ASSIG NED TO THE STORAG E BR ANCH ( 1 ) Grading of D a iry Prod uc e ; ( 2 ) Scien tific R esea r ch i n ’ Study of World s Co n ditions in Dairying ; (4) C orr espondence a l l M atte rs relating to D a iry ing ; ( 5 ) In specti on of Perish a b Can adia n a n d United Kin gdom Po rts ; (6 ) R efrigera to r Ca r D airy Ma rket Intelligence ; (8) Pr omoting Uniformity in 5- n B d ee t "h b on ( 9 ) Ji1 d gi g utter an Ch se a E i iti s ; (10) Cold Storag e Ac t a nd Creamery C ol d Stora ge B onuses ; ” D a i L s a n d ( 1 2 the on an d Its Pr ry aw , ) Utilizati of Milk a Dairy butter as defined by The D iry Industry Act , is butter t a m ade from the milk of less h n fifty cows . -

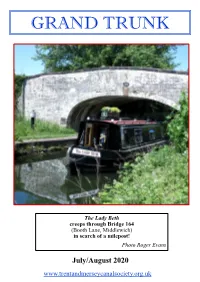

2020 Jul-Aug

GRAND TRUNK The Lady Beth creeps through Bridge 164 (Booth Lane, Middlewich) in search of a milepost! Photo Roger Evans July/August 2020 www.trentandmerseycanalsociety.org.uk Chairman’s Bit Will July 4th be celebrated as “Independence Day” in England now as well as in the USA??? We have been making a short 1-day cruise each week since they were allowed, but on 4th July we will be heading off for our much-delayed annual “Spring” cruise around the “Four Counties Ring” (and Yes, we have booked Harecastle Tunnel). By the time you read this we will be safely back home plan- ning our next outing (probably the Caldon to see if we fit through Froghall Tunnel). How do I know that we will be safely back home before you read this? Simple, because it is Margaret and I who will be posting it to you … What condition will be find our canal in ? Based on our short local outings, I expect to find the towpath almost invisible from the canal in many places and several bottom lock-gates to be much leakier with locks slower to fill. A couple of weeks of busy boat movements will probably get those gates to swell-up and seal better again, but I suspect that the “invisible” towpaths will take longer to reappear. Never mind, we will enjoy our first week’s cruise regardless and some days we may even forget “Covid-19” still exists. That’s what canal boating is all about. Thank you to the 14 people who returned a Gift-Aid form (physically or on- line) after my appeal in the last issue. -

Local Plan Strategy Statement of Consultation (Regulation 22) C

PreSubmission Front green Hi ResPage 1 11/02/2014 14:11:51 Cheshire East Local Plan Local Plan Strategy Statement of Consultation (Regulation 22) C M Y CM MY CY May 2014 CMY K Chapters 1 Introduction 2 2 The Regulations 4 3 Core Strategy Issues and Options Paper (2010) 6 4 Place Shaping (2011) 11 5 Rural Issues (2011) 17 6 Minerals Issues Discussion Paper (2012) 21 7 Town Strategies Phase 1 (2012) 27 8 Wilmslow Vision (Town Strategies Phase 2) (2012) 30 9 Town Strategies Phase 3 (2012) 32 10 Development Strategy and Policy Principles (2013) 36 11 Possible Additional Sites (2013) 43 12 Pre-Submission Core Strategy and Non-Preferred Sites (2013) 46 13 Local Plan Strategy - Submission Version (2014) 52 14 Next Steps 58 Appendices A Consultation Stages 60 B List of Bodies and Persons Invited to Make Representations 63 C Pre-Submission Core Strategy Main Issues and Council's Responses 72 D Non-Preferred Sites Main Issues and Council's Reponses 80 E Local Plan Strategy - Submisson Version Main Issues 87 F Statement of Representations Procedure 90 G List of Media Coverage for All Stages 92 H Cheshire East Local Plan Strategy - Submission Version: List of Inadmissible Representations 103 Contents CHESHIRE EAST Local Plan Strategy Statement of Consultation (Reg 22): May 2014 1 1 Introduction 1.1 This Statement of Consultation sets out the details of publicity and consultation undertaken to prepare and inform the Cheshire East Local Plan Strategy. It sets out how the Local Planning Authority has complied with Regulations 18, 19, 20 and 22 of the Town and Country Planning (Local Planning)(England) Regulations 2012 in the preparation of the Local Plan Strategy (formerly known as the Core Strategy). -

ABC Butter Making, by Burch 30 Harris' Cheese and Butter Maker's Hand Book 1 50 the Jersey, Alderney Aud Ouernsey Cow 1 75 Feeding Animals

ABC BUTTER MAKING Hand-Book for the Beginner. BY F. S. BUI^CH, Editok of The Dairy World. CHICAGO : C. S. BuRCH Publishing Company. 1888. 6S9 Entered according- lo Act of Congress, in the year 1888, by F. S. BURCH, In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at ^Vashington, D. C. CONTENTS. Page MlIiKING 17 Washing the Udder—The Slow Milker — The Jerky Milker—Best Time to Milk- Kicking Cows—Feeding during the Milking — Loud Talking — Milking Tubes — The Stool—The Pail. Cake of Milk 23 Animal Heat — Milk as an Absorbant — Stable Odors—Cooling—Keeping in Pantry or Cellar—Deep Setting—Temperature of the Water—To Raise Cream Quickly—When to Skim. The Milk Room 27 To have well Ventilated—Controlling the Temperature—Pure Air —Management of Cream—Stirring the Cream—Proper Tem- perature at which to keep Cream—Ripen- ing Cream—Straining Cream—Cream in Winter. Butter Color • • • 30 Rich Orange Color — White butter —The — X CONTENTS. Page Juice of Carrots—The Use of Annato—Com- mercial Colors—Beginners generally use too much. Churning 32 The Patent Lightning Churn—Churning too Quickly—The amount of time to prop- erly do the Work—Churning Cream at 60 degrees—Winter Churning — Starting the Churn at a Slow Movement—The Churn with a Dasher—Stopping at the proper time —Granular Butter—Draining off the Butter- milk—Washing in the Churn—To have the . Churn sufficiently Large—Churning whole Milk—The Best Churn for the Dairy. WOEKING THE BuTTEE 38 The Right Temperature—To get the Butter- milk all out—Half Worked Butter—Over- working—Use of the Lever—Working in the Salt—Rule for Salting—Butter Salting Scales. -

Four Counties Ring from Stone | UK Canal Boating

UK Canal Boating Telephone : 01395 443545 UK Canal Boating Email : [email protected] Escape with a canal boating holiday! Booking Office : PO Box 57, Budleigh Salterton. Devon. EX9 7ZN. England. Four Counties Ring from Stone Cruise this route from : Stone View the latest version of this pdf Four-Counties-Ring-from-Stone-Cruising-Route.html Cruising Days : 8.00 to 12.00 Cruising Time : 60.00 Total Distance : 110.00 Number of Locks : 93 Number of Tunnels : 2 Number of Aqueducts : 0 From the Shropshire Union Canal through the rolling Cheshire Plains to the Trent & Mersey Canal, the Staffordshire & Worcester Canal and back via the Shropshire Union the Four Counties Ring is one of the more rural Cruising Rings and is best savoured slowly. The four counties that the routes passes through are Cheshire, Staffordshire, Worcestershire and Shropshire. Highlights include the Industrial Canal Heritage of the Stoke-on-Trent potteries region, the wealthy pasturelands of Cheshire, to the stunning remote sandstone cuttings of Shropshire, as well as the Harecastle Tunnel at 2926 yards one of the longest in Britain and reputed to be haunted by a headless corpse whose body was dumped in the Canal. This is an energetic cruise over 7 days, and more leisurely over 10/11 nights Cruising Notes Day 1 The bulk of Stone lies to the east bank. There is a profusion of services and shops in Stone with the High Street being pedestrianized and lying just a short walk from the canal it is very convenient. South of Stone the trees surrounding the canal thin out somewhat opening up views of land that is flatter than a lot that came before it giving far reaching views across endless farmland. -

CHESHIRE OBSERVER 1 August 5 1854 Runcorn POLICE COURT

CHESHIRE OBSERVER 1 August 5 1854 Runcorn POLICE COURT 28TH ULT John Hatton, a boatman, of Winsford, was charged with being drunk and incapable of taking care of himself on the previous night, and was locked up for safety. Discharged with a reprimand. 2 October 7 1854 Runcorn ROBBERY BY A SERVANT Mary Clarke, lately in the service of Mrs Greener, beerhouse keeper, Alcock Street, was, on Wednesday, charged before Philip Whiteway Esq, at the Town Hall, with stealing a small box, containing 15s 6d, the property of her late mistress. The prisoner, on Monday evening, left Mrs Greener's service, and the property in question was missed shortly afterwards. Early on Tuesday morning she was met by Davis, assistant constable, in the company of John Bradshaw, a boatman. She had then only 3 1/2d in her possession, but she subsequently acknowledged that she had taken the box and money, and said she had given the money to a young man. She was committed to trial for the theft, and Bradshaw, the boatman, was committed as a participator in the offence, but was allowed to find bail for his appearance. 3 April 14 1855 Cheshire Assizes BURGLARY William Gaskell, boatman, aged 24, for feloniously breaking into the dwelling house of Thomas Hughes, clerk, on the night of the 8th August last, and stealing therefrom a silver salver and various other articles. Sentenced to 4 years penal servitude. FORGERY Joseph Bennett, boatman, was indicted for forging an acceptance upon a bill of exchange, with intent to defraud Mr Henry Smith, of Stockport, on the 29th of August last; also with uttering it with the same intent. -

Submission July 2015 Brereton Parish Neighbourhood Plan Brereton Neighbourhood Plan

Brereton Neighbourhood Plan Submission July 2015 Brereton Parish Neighbourhood Plan Brereton Neighbourhood Plan “What you hear from the people of the parish and what you can see with your own eyes is how fortunate we are to live here. With our surrounding local towns expanding by the day we have a responsibility to preserve the best of what we have whilst meeting the needs of current and future generations.” John Charlesworth, Brereton resident and Neighbourhood Plan team member. Page 1 Brereton Parish Neighbourhood Plan About This Document Brereton Parish Neighbourhood Plan Submission This document is the Submission version of the Brereton Parish Neighbourhood Plan (the Plan). Regulation 15 of The Neighbourhood Planning (General) Regulations 2012, directs that the Submission of the Neighbourhood Plan is used to submit to Cheshire East Council for formal consideration and wider consultation. In January 2013 Brereton Parish Council began to develop the Neighbourhood Plan with the aim of shaping the vision for Brereton Parish until 2030. In consultations over the last two years the whole community has helped to develop the Plan. You have told us what changes you would like to see within the Parish and how we can enhance and preserve the things you value most. This Plan and its proposed polices reflects these community aspirations and views, and will significantly influence future planning decisions for new developments within the Parish. Reference to Supporting Documents is widely used throughout the Plan. These references, for example (ref. SD/B01), relate to the table of Supporting Documents listed in Appendix B. The Plan has been prepared by Brereton Parish Council, the qualifying body responsible for creating the Neighbourhood Plan.