Arxiv:1708.00924V2 [Cond-Mat.Stat-Mech]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newtonian Gravity and Special Relativity 12.1 Newtonian Gravity

Physics 411 Lecture 12 Newtonian Gravity and Special Relativity Lecture 12 Physics 411 Classical Mechanics II Monday, September 24th, 2007 It is interesting to note that under Lorentz transformation, while electric and magnetic fields get mixed together, the force on a particle is identical in magnitude and direction in the two frames related by the transformation. Indeed, that was the motivation for looking at the manifestly relativistic structure of Maxwell's equations. The idea was that Maxwell's equations and the Lorentz force law are automatically in accord with the notion that observations made in inertial frames are physically equivalent, even though observers may disagree on the names of these forces (electric or magnetic). Today, we will look at a force (Newtonian gravity) that does not have the property that different inertial frames agree on the physics. That will lead us to an obvious correction that is, qualitatively, a prediction of (linearized) general relativity. 12.1 Newtonian Gravity We start with the experimental observation that for a particle of mass M and another of mass m, the force of gravitational attraction between them, according to Newton, is (see Figure 12.1): G M m F = − RR^ ≡ r − r 0: (12.1) r 2 From the force, we can, by analogy with electrostatics, construct the New- tonian gravitational field and its associated point potential: GM GM G = − R^ = −∇ − : (12.2) r 2 r | {z } ≡φ 1 of 7 12.2. LINES OF MASS Lecture 12 zˆ m !r M !r ! yˆ xˆ Figure 12.1: Two particles interacting via the Newtonian gravitational force. -

1-Crystal Symmetry and Classification-1.Pdf

R. I. Badran Solid State Physics Fundamental types of lattices and crystal symmetry Crystal symmetry: What is a symmetry operation? It is a physical operation that changes the positions of the lattice points at exactly the same places after and before the operation. In other words, it is an operation when applied to an object leaves it apparently unchanged. e.g. A translational symmetry is occurred, for example, when the function sin x has a translation through an interval x = 2 leaves it apparently unchanged. Otherwise a non-symmetric operation can be foreseen by the rotation of a rectangle through /2. There are two groups of symmetry operations represented by: a) The point groups. b) The space groups (these are a combination of point groups with translation symmetry elements). There are 230 space groups exhibited by crystals. a) When the symmetry operations in crystal lattice are applied about a lattice point, the point groups must be used. b) When the symmetry operations are performed about a point or a line in addition to symmetry operations performed by translations, these are called space group symmetry operations. Types of symmetry operations: There are five types of symmetry operations and their corresponding elements. 85 R. I. Badran Solid State Physics Note: The operation and its corresponding element are denoted by the same symbol. 1) The identity E: It consists of doing nothing. 2) Rotation Cn: It is the rotation about an axis of symmetry (which is called "element"). If the rotation through 2/n (where n is integer), and the lattice remains unchanged by this rotation, then it has an n-fold axis. -

Chapter 5 the Relativistic Point Particle

Chapter 5 The Relativistic Point Particle To formulate the dynamics of a system we can write either the equations of motion, or alternatively, an action. In the case of the relativistic point par- ticle, it is rather easy to write the equations of motion. But the action is so physical and geometrical that it is worth pursuing in its own right. More importantly, while it is difficult to guess the equations of motion for the rela- tivistic string, the action is a natural generalization of the relativistic particle action that we will study in this chapter. We conclude with a discussion of the charged relativistic particle. 5.1 Action for a relativistic point particle How can we find the action S that governs the dynamics of a free relativis- tic particle? To get started we first think about units. The action is the Lagrangian integrated over time, so the units of action are just the units of the Lagrangian multiplied by the units of time. The Lagrangian has units of energy, so the units of action are L2 ML2 [S]=M T = . (5.1.1) T 2 T Recall that the action Snr for a free non-relativistic particle is given by the time integral of the kinetic energy: 1 dx S = mv2(t) dt , v2 ≡ v · v, v = . (5.1.2) nr 2 dt 105 106 CHAPTER 5. THE RELATIVISTIC POINT PARTICLE The equation of motion following by Hamilton’s principle is dv =0. (5.1.3) dt The free particle moves with constant velocity and that is the end of the story. -

![Arxiv:1910.10745V1 [Cond-Mat.Str-El] 23 Oct 2019 2.2 Symmetry-Protected Time Crystals](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4942/arxiv-1910-10745v1-cond-mat-str-el-23-oct-2019-2-2-symmetry-protected-time-crystals-304942.webp)

Arxiv:1910.10745V1 [Cond-Mat.Str-El] 23 Oct 2019 2.2 Symmetry-Protected Time Crystals

A Brief History of Time Crystals Vedika Khemania,b,∗, Roderich Moessnerc, S. L. Sondhid aDepartment of Physics, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138, USA bDepartment of Physics, Stanford University, Stanford, California 94305, USA cMax-Planck-Institut f¨urPhysik komplexer Systeme, 01187 Dresden, Germany dDepartment of Physics, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey 08544, USA Abstract The idea of breaking time-translation symmetry has fascinated humanity at least since ancient proposals of the per- petuum mobile. Unlike the breaking of other symmetries, such as spatial translation in a crystal or spin rotation in a magnet, time translation symmetry breaking (TTSB) has been tantalisingly elusive. We review this history up to recent developments which have shown that discrete TTSB does takes place in periodically driven (Floquet) systems in the presence of many-body localization (MBL). Such Floquet time-crystals represent a new paradigm in quantum statistical mechanics — that of an intrinsically out-of-equilibrium many-body phase of matter with no equilibrium counterpart. We include a compendium of the necessary background on the statistical mechanics of phase structure in many- body systems, before specializing to a detailed discussion of the nature, and diagnostics, of TTSB. In particular, we provide precise definitions that formalize the notion of a time-crystal as a stable, macroscopic, conservative clock — explaining both the need for a many-body system in the infinite volume limit, and for a lack of net energy absorption or dissipation. Our discussion emphasizes that TTSB in a time-crystal is accompanied by the breaking of a spatial symmetry — so that time-crystals exhibit a novel form of spatiotemporal order. -

Translational Symmetry and Microscopic Constraints on Symmetry-Enriched Topological Phases: a View from the Surface

PHYSICAL REVIEW X 6, 041068 (2016) Translational Symmetry and Microscopic Constraints on Symmetry-Enriched Topological Phases: A View from the Surface Meng Cheng,1 Michael Zaletel,1 Maissam Barkeshli,1 Ashvin Vishwanath,2 and Parsa Bonderson1 1Station Q, Microsoft Research, Santa Barbara, California 93106-6105, USA 2Department of Physics, University of California, Berkeley, California 94720, USA (Received 15 August 2016; revised manuscript received 26 November 2016; published 29 December 2016) The Lieb-Schultz-Mattis theorem and its higher-dimensional generalizations by Oshikawa and Hastings require that translationally invariant 2D spin systems with a half-integer spin per unit cell must either have a continuum of low energy excitations, spontaneously break some symmetries, or exhibit topological order with anyonic excitations. We establish a connection between these constraints and a remarkably similar set of constraints at the surface of a 3D interacting topological insulator. This, combined with recent work on symmetry-enriched topological phases with on-site unitary symmetries, enables us to develop a framework for understanding the structure of symmetry-enriched topological phases with both translational and on-site unitary symmetries, including the effective theory of symmetry defects. This framework places stringent constraints on the possible types of symmetry fractionalization that can occur in 2D systems whose unit cell contains fractional spin, fractional charge, or a projective representation of the symmetry group. As a concrete application, we determine when a topological phase must possess a “spinon” excitation, even in cases when spin rotational invariance is broken down to a discrete subgroup by the crystal structure. We also describe the phenomena of “anyonic spin-orbit coupling,” which may arise from the interplay of translational and on-site symmetries. -

About Symmetries in Physics

LYCEN 9754 December 1997 ABOUT SYMMETRIES IN PHYSICS Dedicated to H. Reeh and R. Stora1 Fran¸cois Gieres Institut de Physique Nucl´eaire de Lyon, IN2P3/CNRS, Universit´eClaude Bernard 43, boulevard du 11 novembre 1918, F - 69622 - Villeurbanne CEDEX Abstract. The goal of this introduction to symmetries is to present some general ideas, to outline the fundamental concepts and results of the subject and to situate a bit the following arXiv:hep-th/9712154v1 16 Dec 1997 lectures of this school. [These notes represent the write-up of a lecture presented at the fifth S´eminaire Rhodanien de Physique “Sur les Sym´etries en Physique” held at Dolomieu (France), 17-21 March 1997. Up to the appendix and the graphics, it is to be published in Symmetries in Physics, F. Gieres, M. Kibler, C. Lucchesi and O. Piguet, eds. (Editions Fronti`eres, 1998).] 1I wish to dedicate these notes to my diploma and Ph.D. supervisors H. Reeh and R. Stora who devoted a major part of their scientific work to the understanding, description and explo- ration of symmetries in physics. Contents 1 Introduction ................................................... .......1 2 Symmetries of geometric objects ...................................2 3 Symmetries of the laws of nature ..................................5 1 Geometric (space-time) symmetries .............................6 2 Internal symmetries .............................................10 3 From global to local symmetries ...............................11 4 Combining geometric and internal symmetries ...............14 -

Derivation of Generalized Einstein's Equations of Gravitation in Some

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 5 February 2021 doi:10.20944/preprints202102.0157.v1 Derivation of generalized Einstein's equations of gravitation in some non-inertial reference frames based on the theory of vacuum mechanics Xiao-Song Wang Institute of Mechanical and Power Engineering, Henan Polytechnic University, Jiaozuo, Henan Province, 454000, China (Dated: Dec. 15, 2020) When solving the Einstein's equations for an isolated system of masses, V. Fock introduces har- monic reference frame and obtains an unambiguous solution. Further, he concludes that there exists a harmonic reference frame which is determined uniquely apart from a Lorentz transformation if suitable supplementary conditions are imposed. It is known that wave equations keep the same form under Lorentz transformations. Thus, we speculate that Fock's special harmonic reference frames may have provided us a clue to derive the Einstein's equations in some special class of non-inertial reference frames. Following this clue, generalized Einstein's equations in some special non-inertial reference frames are derived based on the theory of vacuum mechanics. If the field is weak and the reference frame is quasi-inertial, these generalized Einstein's equations reduce to Einstein's equa- tions. Thus, this theory may also explain all the experiments which support the theory of general relativity. There exist some differences between this theory and the theory of general relativity. Keywords: Einstein's equations; gravitation; general relativity; principle of equivalence; gravitational aether; vacuum mechanics. I. INTRODUCTION p. 411). Theoretical interpretation of the small value of Λ is still open [6]. The Einstein's field equations of gravitation are valid 3. -

PHYS 402: Electricity & Magnetism II

PHYS 610: Electricity & Magnetism I Due date: Thursday, February 1, 2018 Problem set #2 1. Adding rapidities Prove that collinear rapidities are additive, i.e. if A has a rapidity relative to B, and B has rapidity relative to C, then A has rapidity + relative to C. 2. Velocity transformation Consider a particle moving with velocity 푢⃗ = (푢푥, 푢푦, 푢푧) in frame S. Frame S’ moves with velocity 푣 = 푣푧̂ in S. Show that the velocity 푢⃗ ′ = (푢′푥, 푢′푦, 푢′푧) of the particle as measured in frame S’ is given by the following expressions: 푑푥′ 푢푥 푢′푥 = = 2 푑푡′ 훾(1 − 푣푢푧/푐 ) 푑푦′ 푢푦 푢′푦 = = 2 푑푡′ 훾(1 − 푣푢푧/푐 ) 푑푧′ 푢푧 − 푣 푢′푧 = = 2 푑푡′ (1 − 푣푢푧/푐 ) Note that the velocity components perpendicular to the frame motion are transformed (as opposed to the Lorentz transformation of the coordinates of the particle). What is the physics for this difference in behavior? 3. Relativistic acceleration Jackson, problem 11.6. 4. Lorenz gauge Show that you can always find a gauge function 휆(푟 , 푡) such that the Lorenz gauge condition is satisfied (you may assume that a wave equation with an arbitrary source term is solvable). 5. Relativistic Optics An astronaut in vacuum uses a laser to produce an electromagnetic plane wave with electric amplitude E0' polarized in the y'-direction travelling in the positive x'-direction in an inertial reference frame S'. The astronaut travels with velocity v along the +z-axis in the S inertial frame. a) Write down the electric and magnetic fields for this propagating plane wave in the S' inertial frame – you are free to pick the phase convention. -

The Lorentz Transformation

The Lorentz Transformation Karl Stratos 1 The Implications of Self-Contained Worlds It sucks to have an upper bound of light speed on velocity (especially for those who demand space travel). Being able to loop around the globe seven times and a half in one second is pretty fast, but it's still far from infinitely fast. Light has a definite speed, so why can't we just reach it, and accelerate a little bit more? This unfortunate limitation follows from certain physical facts of the universe. • Maxwell's equations enforce a certain speed for light waves: While de- scribing how electric and magnetic fields interact, they predict waves that move at around 3 × 108 meters per second, which are established to be light waves. • Inertial (i.e., non-accelerating) frames of reference are fully self-contained, with respect to the physical laws: For illustration, Galileo observed in a steadily moving ship that things were indistinguishable from being on terra firma. The physical laws (of motion) apply exactly the same. People concocted a medium called the \aether" through which light waves trav- eled, like sound waves through the air. But then inertial frames of reference are not self-contained, because if one moves at a different velocity from the other, it will experience a different light speed with respect to the common aether. This violates the results from Maxwell's equations. That is, light beams in a steadily moving ship will be distinguishable from being on terra firma; the physical laws (of Maxwell's equations) do not apply the same. -

Arxiv:Gr-Qc/0507001V3 16 Oct 2005

October 29, 2018 21:28 WSPC/INSTRUCTION FILE ijmp˙october12 International Journal of Modern Physics D c World Scientific Publishing Company Gravitomagnetism and the Speed of Gravity Sergei M. Kopeikin Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Missouri-Columbia, Columbia, Missouri 65211, USA [email protected] Experimental discovery of the gravitomagnetic fields generated by translational and/or rotational currents of matter is one of primary goals of modern gravitational physics. The rotational (intrinsic) gravitomagnetic field of the Earth is currently measured by the Gravity Probe B. The present paper makes use of a parametrized post-Newtonian (PN) expansion of the Einstein equations to demonstrate how the extrinsic gravitomag- netic field generated by the translational current of matter can be measured by observing the relativistic time delay caused by a moving gravitational lens. We prove that mea- suring the extrinsic gravitomagnetic field is equivalent to testing relativistic effect of the aberration of gravity caused by the Lorentz transformation of the gravitational field. We unfold that the recent Jovian deflection experiment is a null-type experiment testing the Lorentz invariance of the gravitational field (aberration of gravity), thus, confirming existence of the extrinsic gravitomagnetic field associated with orbital motion of Jupiter with accuracy 20%. We comment on erroneous interpretations of the Jovian deflection experiment given by a number of researchers who are not familiar with modern VLBI technique and subtleties of JPL ephemeris. We propose to measure the aberration of gravity effect more accurately by observing gravitational deflection of light by the Sun and processing VLBI observations in the geocentric frame with respect to which the Sun arXiv:gr-qc/0507001v3 16 Oct 2005 is moving with velocity ∼ 30 km/s. -

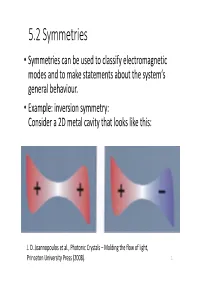

5.2 Symmetries • Symmetries Can Be Used to Classify Electromagnetic Modes and to Make Statements About the System‘S General Behaviour

5.2 Symmetries • Symmetries can be used to classify electromagnetic modes and to make statements about the system‘s general behaviour. • Example: inversion symmetry: Consider a 2D metal cavity that looks like this: J. D. Joannopoulos et al., Photonic Crystals – Molding the flow of light, Princeton University Press (2008). 1 • The shape is somewhat arbitrary, making an analytical solution difficult, but it has inversion symmetry if is a mode with frequency , then must also be a mode with frequency • Unless is a member of a degenerate family of modes, then if has the same frequency, it must be the same mode, i.e. it must be a multiple of : . • If we invert the system twice we obtain or . • A given nondegenerate mode must be of one of the two types, either it is invariant under inversion (even mode) or it becomes its own opposite (odd mode). • Thereby we have classified the modes of the system based on how they respond to one of its symmetry operations. 2 • Let‘s capture this idea in a more abstract language • Suppose is an operator (a 3x3 matrix) that inverts vectors (3x1 matrices), so that • To invert a vector field, we need an operator that inverts both the vector and ist argument : • For an inversion symmetric system it does not matter if we operate with or if we first invert the coordinates, then operate with , and then change them back, i.e.: (73) • This equation can be rearranged: =0 • We can define the commutator (74) which is itself an operator 3 • For our inversion symmetric example system we have ,Θ 0. -

![Arxiv:2108.07786V2 [Physics.Class-Ph] 18 Aug 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5874/arxiv-2108-07786v2-physics-class-ph-18-aug-2021-1795874.webp)

Arxiv:2108.07786V2 [Physics.Class-Ph] 18 Aug 2021

Demystifying the Lagrangians of Special Relativity Gerd Wagner1, ∗ and Matthew W. Guthrie2, † 1Mayener Str. 131, 56070 Koblenz, Germany 2 Department of Physics, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT 06269 (Dated: August 19, 2021) Special relativity beyond its basic treatment can be inaccessible, in particular because introductory physics courses typically view special relativity as decontextualized from the rest of physics. We seek to place special relativity back in its physics context, and to make the subject approachable. The Lagrangian formulation of special relativity follows logically by combining the Lagrangian approach to mechanics and the postulates of special relativity. In this paper, we derive and explicate some of the most important results of how the Lagrangian formalism and Lagrangians themselves behave in the context of special relativity. We derive two foundations of special relativity: the invariance of any spacetime interval, and the Lorentz transformation. We then develop the Lagrangian formulation of relativistic particle dynamics, including the transformation law of the electromagnetic potentials, 2 the Lagrangian of a relativistic free particle, and Einstein’s mass-energy equivalence law (E = mc ). We include a discussion of relativistic field Lagrangians and their transformation properties, showing that the Lagrangians and the equations of motion for the electric and magnetic fields are indeed invariant under Lorentz transformations. arXiv:2108.07786v2 [physics.class-ph] 18 Aug 2021 ∗ [email protected] † [email protected] 2 I. Introduction A. Motivation Lagrangians link the relationship between equations of motion and coordinate systems. This is particularly impor- tant for special relativity, the foundations of which lie in considering the laws of physics within different coordinate systems (i.e., inertial reference frames).