Craft Beer in Portugal – a Study About Consumers, Perceptions, Drivers and Barriers of Consumption

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9570/18 ADD 1 REV 1 PR/Cs DGG 2B EN

Council of the European Union Brussels, 8 June 2018 (OR. en) 9570/18 Interinstitutional File: ADD 1 REV 1 2018/0173 (CNS) FISC 238 ECOFIN 546 IA 164 COVER NOTE No. Cion doc.: SWD(2018) 259 final/2 Subject: COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT IMPACT ASSESSMENT Accompanying the document Proposal for a Council Directive amending Directive 92/83/EEC on the harmonization of the structures of excise duties on alcohol and alcoholic beverages Delegations will find attached document SWD(2018) 259 final/2. Encl.: SWD(2018) 259 final/2 9570/18 ADD 1 REV 1 PR/cs DGG 2B EN EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 7.6.2018 SWD(2018) 259 final /2 This document corrects document SWD(2018) 259 final of 25.05.2018. The annexes were not included. The text shall read as follows: COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT IMPACT ASSESSMENT Accompanying the document Proposal for a Council Directive amending Directive 92/83/EEC on the harmonization of the structures of excise duties on alcohol and alcoholic beverages {COM(2018) 334 final} - {SEC(2018) 254 final} - {SWD(2018) 258 final} EN EN CONTENTS 1. Introduction and Context .......................................................................................................... 4 1.1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 4 1.2. Scope for reforms ....................................................................................................................... 5 2. What is the problem and why is it a problem? ........................................................................ -

Sensory & Emotional Profiling of Wine, Beer and Non-Alcoholic Beer

Propositions 1. Wine is calm and loving, beer is adventurous and energetic. (this thesis) 2. The name of “non-alcoholic beer” is a key part in its failure. (this thesis) 3. The lengthy process of scienti c publishing is slowing down the progress of science and innovation. 4. Metaphorical meaning of words are more valuable than p-values. 5. Consumers will always provide an answer, even to silly questions. 6. Only the Dutch correctly refer to the weather for their mood status. Propositions belonging to the PhD thesis, entitled: ‘A fl avour of emotions: sensory & emotional profi ling of wine, beer and non-alcoholic beer’ Ana Patrícia Silva Wageningen, June 26th, 2017 A flavour of emotions Sensory & emotional profiling of wine, beer and non-alcoholic beer Ana Patrícia Silva Thesis committee Promotor Prof. Dr Kees de Graaf Professor of Sensory Science and Eating Behaviour Wageningen University & Research Co-promotors Dr Gerry Jager Associate professor, Division of Human Nutrition Wageningen University & Research Dr Manuela Pintado Associate professor, Escola Superior de Biotecnologia Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Portugal Other members Prof. Dr Edith J.M. Feskens, Wageningen University & Research Dr Carolina Chaya, Technical University of Madrid, Spain Prof. Dr Emely W.M.L. de Vet, Wageningen University & Research Dr Elizabeth H. Zandstra, Unilever R&D Vlaardingen, the Netherlands This research was conducted under the auspices of the Graduate School VLAG (Advanced studies in Food Technology, Agrobiotechnology, Nutrition and Health Sciences). A flavour of emotions Sensory & emotional profiling of wine, beer and non-alcoholic beer Ana Patrícia Silva Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of doctor at Wageningen University by the authority of the Rector Magnificus Prof. -

Thoughts on 1000 Beers

TThhoouugghhttss OOnn 11000000 BBeeeerrss DDaavviidd GGooooddyy Thoughts On 1000 Beers David Goody With thanks to: Friends, family, brewers, bar staff and most of all to Katherine Shaw Contents Introduction 3 Belgium 85 Britain 90 Order of Merit 5 Czech Republic 94 Denmark 97 Beer Styles 19 France 101 Pale Lager 20 Germany 104 Dark Lager 25 Iceland 109 Dark Ale 29 Netherlands 111 Stout 36 New Zealand 116 Pale Ale 41 Norway 121 Strong Ale 47 Sweden 124 Abbey/Belgian 53 Wheat Beer 59 Notable Breweries 127 Lambic 64 Cantillon 128 Other Beer 69 Guinness 131 Westvleteren 133 Beer Tourism 77 Australia 78 Full Beer List 137 Austria 83 Introduction This book began with a clear purpose. I was enjoying Friday night trips to Whitefriars Ale House in Coventry with their ever changing selection of guest ales. However I could never really remember which beers or breweries I’d enjoyed most a few months later. The nearby Inspire Café Bar provided a different challenge with its range of European beers that were often only differentiated by their number – was it the 6, 8 or 10 that I liked? So I started to make notes on the beers to improve my powers of selection. Now, over three years on, that simple list has grown into the book you hold. As well as straightforward likes and dislikes, the book contains what I have learnt about the many styles of beer and the history of brewing in countries across the world. It reflects the diverse beers that are being produced today and the differing attitudes to it. -

Read the Impact Assessment

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 7.6.2018 SWD(2018) 259 final /2 This document corrects document SWD(2018) 259 final of 25.05.2018. The annexes were not included. The text shall read as follows: COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT IMPACT ASSESSMENT Accompanying the document Proposal for a Council Directive amending Directive 92/83/EEC on the harmonization of the structures of excise duties on alcohol and alcoholic beverages {COM(2018) 334 final} - {SEC(2018) 254 final} - {SWD(2018) 258 final} EN EN CONTENTS 1. Introduction and Context .......................................................................................................... 4 1.1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 4 1.2. Scope for reforms ....................................................................................................................... 5 2. What is the problem and why is it a problem? ......................................................................... 5 2.1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 5 2.2. Scope of the problems................................................................................................................ 6 2.3. Problem 1 - Dysfunctions in the application of exemptions for denatured alcohol .................. 6 2.4. Problem 2 – Dysfunctions in the classification of certain alcoholic beverages ........................10 -

International Beer Market: Drivers and Challenges of Development

ASSOCIAÇÃO DE POLITÉCNICOS DO NORTE (APNOR) INSTITUTO POLITÉCNICO DE BRAGANÇA International beer market: drivers and challenges of development Astapenka Kseniya Final Dissertation presented to Instituto Politécnico de Bragança To obtain the Master Degree in Management, Specialisation in Business Management Supervisors: Ana Paula Monte Alena Petrushkevich Bragança, may, 2018. ASSOCIAÇÃO DE POLITÉCNICOS DO NORTE (APNOR) INSTITUTO POLITÉCNICO DE BRAGANÇA International beer market: drivers and challenges of development Astapenka Kseniya Supervisors: Ana Paula Monte Alena Petrushkevich Bragança, may, 2018. Abstract The uncertain conditions in the beer market related with the tendency on downsizing of consumption of alcoholic beverages in favour to non alcoholic ones have invoked the need to determine competitive advantages of the brewery companies in the international market. At the same time, it is interesting to analyse competitiveness of Belarussian and Portuguese breweries in the international beer market taking into account different location, finance, government regulation, etc. The main purpose of this research is to study the situation in the International beer market in order to estimate the prospects of Belarussian and Portuguese beer companies’ development. Therefore, the objectives of the research are (i) to analyse international beer market, dynamics of sale volumes and prices, regulatory framework; (ii) to analyse Belarussian and Portuguese beer market and to determine its prospects; and (iii) to analyse competitiveness of Belarussian and Portuguese breweries in the international beer market. To achieve these objectives, it was applied techniques and methods to analyse the competitiveness of the market such as Porter’s analysis, SWOT and PEST analysis and others, using qualitative and quantitative analysis, secondary and primarily data (using sources from OECD databases, national institute of statistics and government statistics and others). -

Contribution Made by Beer to the European Economy Full Report - December 2013

The Contribution made by Beer to the European Economy Full Report - December 2013 The Brewers of Europe The Contribution made by Beer to the European Economy Full Report Bram Berkhout Lianne Bertling Yannick Bleeker Walter de Wit (EY) Geerten Kruis Robin Stokkel Ri-janne Theuws Amsterdam, December 2013 A report commissioned by The Brewers of Europe and conducted by Regioplan Policy Research and EY The Brewers of Europe ISBN 978-2-9601382-2-1 EAN 9782960138221 © Published December 2013 4 The Contribution made by Beer to the European Economy ChapterTable of Titlecontents here Table of contents 5 Table of contents Introduction ...............................................................................................................6 Foreword by The President of The Brewers of Europe ...............................................8 Executive summary .................................................................................................10 01 A sector with global presence .................................................................................13 02 A sector with impact ...............................................................................................19 03 The impact on suppliers ..........................................................................................30 04 The impact on the hospitality sector ........................................................................41 05 Government revenues .............................................................................................51 Countries -

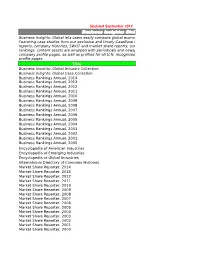

Reference Title List 2-2012

Updated September 2014 Business Insights: Global Business Insights: Global lets users easily compare global economies, companies and industries. Featuring case studies from our exclusive and timely CaseBase collection, global industry research reports, company histories, SWOT and market share reports, corporate chronologies, and business rankings, content assets are wrapped with periodicals and newspapers in hundreds of thousands of company profile pages, as well as profiles for all U.N. recognized countries and hundreds of industry profile pages. Title Business Insights: Global Industry Collection Business Insights: Global Case Collection Business Rankings Annual, 2014 Business Rankings Annual, 2013 Business Rankings Annual, 2012 Business Rankings Annual, 2011 Business Rankings Annual, 2010 Business Rankings Annual, 2009 Business Rankings Annual, 2008 Business Rankings Annual, 2007 Business Rankings Annual, 2006 Business Rankings Annual, 2005 Business Rankings Annual, 2004 Business Rankings Annual, 2003 Business Rankings Annual, 2002 Business Rankings Annual, 2001 Business Rankings Annual, 2000 Encyclopedia of American Industries Encyclopedia of Emerging Industries Encyclopedia of Global Industries International Directory of Company Histories Market Share Reporter, 2014 Market Share Reporter, 2013 Market Share Reporter, 2012 Market Share Reporter, 2011 Market Share Reporter, 2010 Market Share Reporter, 2009 Market Share Reporter, 2008 Market Share Reporter, 2007 Market Share Reporter, 2006 Market Share Reporter, 2005 Market Share Reporter, -

In This Edition Hybrid Theory Tribute Band Set for Global Domination

FREE JULY 2021 | EDITION 116 In this edition Hybrid Theory Tribute Band Set for global domination A Modern History of Portugal Told by author Barry Hatton Turning Over a New Leaf The Portuguese art of basket making Once Upon a Time An internationally renowned doll artist Indian Tand��ri Re�taurant ��������10% On all Take Aways We would like to inform our customers that we are Plus a Poppadums and chutney tray following all the hygiene and safety regulations ‘on the house’ recommended, to help us implement these regulations please call in advance to book your table. Scan the QR code to see our menu Call to place your order: Largo Portas de Portugal 14, 8600-657 Lagos (Near Repsol garage o Avenida) 00351 282 762 249 www.delhidarbar.eu | 00351 282 762 249 | 00351 923 206 701 00351 923 206 701 REF.: 10164 BARÃO DE SÃO MIGUEL 4.400 sqm of land with with permission to build a large villa, featuring panoramic countryside views and good access. € 350,000 LAND SPACE 4,400 M² SCAN FOR MORE DETALS Algarve Real Estate Agents, specialising in properties for sale in the Western Algarve EN - 125, Entrada do Parque da Floresta 8650 - 060 Budens www.ppiestateagents.com +351 282 698 621 / 926 035 326 [email protected] Michelle and Barry Sadler Editor's note I am dedicating the July issue of the Tomorrow magazine to my mother-in-law Michelle Sadler who passed away on 13 June. The last interaction I had with her was as she left my house, following a birthday tea for my daughter.