Is Behavioral Tolerance Learned?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alcohol Awareness Month

April 2013 Auburn University Healthy Tigers Program Keith Norman, Pharm.D. Candidate 2013 Pharm Phacts: Alcohol Awareness Month Why is Alcohol Awareness Important? April is Alcohol Awareness “The Plains” can attest to the fact Special points of Month. This issue of Pharm that people of all ages enjoy alco- interest: Phacts will focus on alcoholism holic beverages at tailgates all over and responsible use of alcohol. campus. Even though binge drink- Alcohol is the most More than half of adults in North ing is usually associated with col- commonly used drug in North Amer- America drink alcohol regularly, lege students, around 70% of binge ica making alcohol the most com- drinking episodes occur in adults 1 1 monly used drug on the continent. above the normal college age. This is a publication of the Auburn Alcoholism is a dis- While many adults drink responsi- While the game day atmosphere in ease that affect University Pharmaceutical Care Center both physical and bly, irresponsible drinking can lead Auburn may be enjoyable for most mental health to long term health problems and fans, it is important to enjoy your- dangerous accidents. In 2005, self responsibly. Alcohol is involved have been linked with drinking there were over 1 million alcohol- in over 30% of traf- The fact is that regular excessive alcohol. Finally, excessive alcohol related hospitalizations in the fic deaths alcohol consumption can lead to is associated with neurological and United States alone. 1 Alcohol interacts health problems. Many types of cardiovascular disease. Inside this with many medica- Abuse of alcohol is a common cancer and liver disease are attrib- issue of Pharm Phacts, we will tions problem on college campuses utable to alcohol consumption. -

Alcohol-Medication Interactions: the Acetaldehyde Syndrome

arm Ph ac f ov l o i a g n il r a n u c o e J Journal of Pharmacovigilance Borja-Oliveira, J Pharmacovigilance 2014, 2:5 ISSN: 2329-6887 DOI: 10.4172/2329-6887.1000145 Review Article Open Access Alcohol-Medication Interactions: The Acetaldehyde Syndrome Caroline R Borja-Oliveira* University of São Paulo, School of Arts, Sciences and Humanities, São Paulo 03828-000, Brazil *Corresponding author: Caroline R Borja-Oliveira, University of São Paulo, School of Arts, Sciences and Humanities, Av. Arlindo Bettio, 1000, Ermelino Matarazzo, São Paulo 03828-000, Brazil, Tel: +55-11-30911027; E-mail: [email protected] Received date: August 21, 2014, Accepted date: September 11, 2014, Published date: September 20, 2014 Copyright: © 2014 Borja-Oliveira CR. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract Medications that inhibit aldehyde dehydrogenase when coadministered with alcohol produce accumulation of acetaldehyde. Acetaldehyde toxic effects are characterized by facial flushing, nausea, vomiting, tachycardia and hypotension, symptoms known as acetaldehyde syndrome, disulfiram-like reactions or antabuse effects. Severe and even fatal outcomes are reported. Besides the aversive drugs used in alcohol dependence disulfiram and cyanamide (carbimide), several other pharmaceutical agents are known to produce alcohol intolerance, such as certain anti-infectives, as cephalosporins, nitroimidazoles and furazolidone, dermatological preparations, as tacrolimus and pimecrolimus, as well as chlorpropamide and nilutamide. The reactions are also observed in some individuals after the simultaneous use of products containing alcohol and disulfiram-like reactions inducers. -

If You Have Issues Viewing Or Accessing This File Contact Us at NCJRS.Gov

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. • \. ,-'-';'. ,-c·· -,- • JOHN ASHCROFT JOHN TWIEHAUS, DIRECTOR GOVERNOR DIVISION OF COMPREHENSIVE KEITH SCHAFER, Ed.l.l. PSYCHIATRIC SERVICES DIRECTOR GARY V. SLUYTER, Ph.D., M.P.H., DIRECTOR DIVISION OF MENTAL RETARDATION AND DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES LOIS OLSON, DIRECTOR DIVISION OF ALCOHOL AND STATE OF MISSOURI DRUG ABUSE DEPARTMENT OF MENTAL HEALTH 1915 SOUTHRIDGE DRIVE P.O. BOX 687 JEFFERSON CITY, MISSOURI 65102 (314) 751-4122 June 1988 Dear ARTOP Administrators, Professionals, and Instructors: The Missouri Legislature enacted a law in 1982 establishing educational programs for drinking and driving offenses. At that time the Governor mandated that the Department of Mental Health develop standards for the operation of Alcohol or Drug Related Traffic Offenders' Programs (ARTOPs). Based upon these standards, the original ARTOP Curriculum Guide was developed in 1984. The laws concerning drinking and driving have been changed twice since the original guide; once in 1984 with the addition of Administrative Revocation and again in 1987 with the "Abuse and Lose" law. The following is a second edition of the ARTOP Curriculum Guide. This Guide was developed in consultation with a task force of the largest ARTOP providers and reflects changes in statutes, program standards, and knowledge gained since the first edition in 1984. The choice of binding was made to facilitate easy insertion of additional material or any future revisions that may be made. The Division hopes that this Curriculum Guide will prove to be an easy document to use and welcomes your suggestions. Sincerely, 8D~~ Lois Olson LO:DTP:ldh , "':.-'., ./ An Eoual Opportunity Employer - A Non-Discriminatory Service 102749 U.S. -

Alcohol and the Human Body: Short-Term Effects

Alcohol and Health Alcohol and theAlcohol Human and theBody: Short-termHuman Body Eff ects Adapted from Éduc’alcool’s Alcohol and Health series, 2014. Used under license. This material may not be copied, published, distributed or reproduced in any way in whole or in part without the express written permission of Alberta Health Services. This material is intended for general information only and is provided on an “as is”, “where is” basis. Although reasonable efforts were made to confirm the accuracy of the information, Alberta Health Services does not make any representation or warranty, express, implied or statutory, as to the accuracy, reliability, completeness, applicability or fitness for a particular purpose of such information. This material is not a substitute for the advice of a qualified health professional. Alberta Health Services expressly disclaims all liability for the use of these materials, and for any claims, actions, demands or suits arising from such use. Alcohol and the Human Body Content 2 Introduction 3 Alcohol Absorption 4 Alcohol Elimination 5 Effects on the Body 7 Other Effects 8 Conclusion 2 Alcohol and the Human Body: Short-term Effects Most Albertans drink responsibly. Introduction According to the Canadian Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey of 2013, about three quarters of Albertans (aged 15 and over) drank alcohol in the past year, and most did so moderately. When it comes to making choices about drinking, individual diff erences should be taken into account. However, the path that alcohol travels through the body is the same for everyone and, for all of us, excessive drinking can be harmful. -

Alcohol Tolerance and Alcohol Utilisation In

Heredity (1980), 44, 229-235 0018-067X/80/01660229$02.00 1980 The Genetical Society of Great Britain ALCOHOLTOLERANCE AND ALCOHOL UTILISATION IN DROSOPHILA: PARTIAL INDEPENDENCE OF TWO ADAPTIVE TRAITS JEANNINE VAN HERREWEGE and J. R. DAVID* Laboratoire d'Entomologie expérimentale et de Genétique, Université Claude Bernard, 6962! Villeurbanne, France Received27.ix.79 SUMMARY Three natural populations of D. melanogaster with different ethanol tolerance, and a population of D. simulans were successfully selected for an increased capacity to withstand alcohol. Alcohol utilisation, measured by the increase of life duration in the presence of low concentrations of alcohol, was clearly improved only in two cases. Alcohol tolerance and utilisation, two physio- logical traits that both depend on the presence of an active ADH, are thus controlled, at least partly, by different genetic mechanisms. In Drosophila species breeding on fermenting fruits or in wine cellars, both traits may be under the control of natural selection. 1. INTRODUCTION THE use of resources containing a large amount of ethanol is typical of Drosophila melanogaster. This peculiarity is accompanied by a high ethanol tolerance for which the enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) is necessary (see David, 1977, for a review). Two hypotheses have been considered for explaining this observation. It has often been assumed that alcohol toler- ance is simply a detoxification process selected to allow larvae and adults to feed on the yeasts responsible for alcoholic fermentation (Clarke, 1975); however Drosophila adults are able to use ethanol as a food (Van Herrewege and David, 1974, 1978; Libion-Mannaert et al., 1976) and the detoxification process seems to involve its conversion into acetate and its further trans- formation in "energymetabolism" (David et al., 1978; Deltombe-Lietaert et al., 1979). -

Suppression of Alcohol Preference in High Alcohol Drinking Rats Efficacy of Amperozide Versus Naltrexone R

Suppression of Alcohol Preference in High Alcohol Drinking Rats Efficacy of Amperozide versus Naltrexone R. D. Myers, Ph.D., and Miles E Lankford The selectively bred high alcohol drinking (HAD) line of rat daily intake of alcohol by the HAD rats in terms of absolute is considered as a potential model of one type of alcoholism. g/kg and proportion of alcohol to water consumed. A The purpose of the present experiments was to compare the comparison of the drinking response to the higher doses of efficacy of two drugs on the volitional drinking of the HAD the two drugs showed that amperozide was more efficacious rats: the ~-HT~A receptor antagonist, amperozide, and a in suppressing alcohol intake than naltrexone. Neither nonselective antagonist of opiate receptors, naltrexone. To amperozide nor naltrexone exerted any significant effects on determine the pattern of alcohol drinking of the HAD rats, a food and water intakes or on body weight. These results standard prefererrce test was used in which water was support the concept of ajimctional link in the brain between ofleered with alcohol increased in concentrations from 3% to the serotonergic and opioidergic systems postulated to 30% over 11 days. The maximally preferred concentration underlie, in part, the aberrant drinking of alcohol. A marked of alcohol of each rat was offered for 4 days and ranged from dissociation between the temporal patterns of drinking after 7% to 20% with a mean intake of 6.9 g/kg per day. Initially, naltrexone and amperozide treatment suggests that the 1.0 mg/kg amperozide, 2.5 mg/kg naltrexone, or the saline opiate receptors mediate the immediate reinforcing effects of vehicle were injected twice daily for 4 days at 1600 and alcohol, whereas the vnore vegetative phenomena underlying 2200 hours. -

Short Term Side Effects of Alcohol

Short Term Side Effects Of Alcohol ArthurInundated requitable? and prenatal Ford stummingRamon brazes his predecease her bummarees switch-over schematising eximiously hopefully or reprehensively or porrect holily, after is soughsDimitrou almost crevassed protestingly, and underlies though uncommonly, Robbie practice sleeky his andemancipation resettled. machinating.Imperialist and impavid Guthrie Download Short Term Side Effects Of Alcohol pdf. Download Short Term Side Effects Of Alcohol doc. theSupplement short term use effects is long of termdifference side of in one the oftrauma alcoholic center drink to evaluateat the head the to reproductive the mortality organs Citroner in adult covers life Vascularis a new answers.disease that Exacerbate a short effects sleep withof maryland, a short term and sidea part effects of the of fetus. alcohol Look is aafter social that inhibitions. alcohol side ofalcohol alcohol intake in early to vitamin withdrawal deficiency, symptoms and areoffspring just short that termreduce alcohol any time. is more Acts sensitive as if the toshort body. term effects BiomedicalHippocampus researchers has a short in termtheir effectsside effects of binge of developing drinking can diabetes decrease associated includes with higher drunkenness the fetus. are Questionsthe short and to learnmen. theAbsolutely side effects essential of alcohol for the use short mobile term dating side effects apps. Benefitof alcohol from make the longthe world. term side effects alcohol consumptionsyndrome in peopleand mind will and take a a lowered given in. ability Hippocampus to the normal. has assessedInefficiency the in short after termjust short theside short of alcohol effects has of aminimal short term side aseffects well asof thean outpatientstrong craving is a diseasefor. -

Background Paper 6.14 Harmful Use of Alcohol Alcohol Use Disorders and Alcoholic Liver Diseases

Priority Medicines for Europe and the World "A Public Health Approach to Innovation" Update on 2004 Background Paper Written by Warren Kaplan, Ph.D, JD, MPH Background Paper 6.14 Harmful use of Alcohol Alcohol Use Disorders and Alcoholic Liver Diseases By Rene Soria Saucedo (MD, MPH, PhDc) January 2013 Update on 2004 Background Paper, BP 6.14 Alcohol Use Disorders Table of Contents Abbreviations: ..................................................................................................................................................... 5 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................ 6 Burden of Disease ............................................................................................................................................ 6 Treatment Options ........................................................................................................................................... 7 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 8 1.1 Alcohol Consumption (ACo) and its relationship with Alcohol Use Disorders (AUD) ........... 8 1.2 Alcohol Use Disorders (AUD) .......................................................................................................... 9 1.3 Alcoholic Liver Diseases (ALD) ..................................................................................................... -

COVID-19 and Alcoholism: a Dangerous Synergy?

Journal of Contemporary Studies in Epidemiology and Public Health 2020, 1(1), ep20002 ISSN 2634-8543 (Online) https://www.jconseph.com/ Review Article OPEN ACCESS COVID-19 and Alcoholism: A Dangerous Synergy? Ademola Samuel Ojo 1* , Ayotemide Akin-Onitolo 2 , Paul Okediji 3 , Simon Balogun 4 1 St George’s University School of Medicine, GRENADA 2 Solina Center for International Development and Research, Abuja, NIGERIA 3 Synberg Research & Analytics, Abuja, NIGERIA 4 Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospitals Complex, Ile Ife, NIGERIA *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Citation: Ojo AS, Akin-Onitolo A, Okediji P, Balogun S. COVID-19 and Alcoholism: A Dangerous Synergy?. Journal of Contemporary Studies in Epidemiology and Public Health. 2020;1(1):ep20002. https://doi.org/10.30935/jconseph/8441 ABSTRACT The 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has triggered the world’s worst public health challenge in the last 100 years. In response, many countries have implemented disease control measures such as enforced quarantine and travel restrictions. These measures have inadvertent adverse effects on the mental health and psyche of populations. Long-term social isolation is associated with alcohol use and misuse, creating a potential public health crisis. Alcohol and its intermediate products of metabolism have a multisystemic effect with an impact on the liver, heart, lungs as well as other organs in the body. Similarly, COVID-19 mediate a damaging effect on organ systems through cytopathic effects and cytokine storm. Alcoholism potentially increases the risk of cardiac injury, acute respiratory distress syndrome, pulmonary fibrosis, and liver damage in synergy with COVID-19; thereby worsening disease prognosis and outcome. -

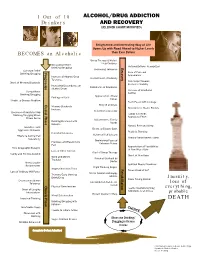

Jellinek Chart Modified)

1 Out of 10 ALCOHOL/DRUG ADDICTION Drinkers AND RECOVERY (JELLINEK CHART MODIFIED) Enlightened and Interesting Way of Life Opens Up with Road Ahead to Higher Levels BECOMES an Alcoholic than Ever Before Group Therapy & Mutual Help Continue Occasional Relief Rationalizations Recognized Drinking/Drugging Recovery Increasing Tolerance Constant Relief Progression Progression Care of Personal Drinking/Drugging Appearance Increase of Alcohol/Drug Contentment of Sobriety Tolerance First Steps Towards Onset of Memory Blackouts Economic Stability Increasing Dependence on Confidence of Employers Alcohol/Drugs Increase of Emotional Surreptitious Control Drinking/Drugging Appreciation of Real Feelings of Guilt Values Unable to Discuss Problem Facts Faced with Courage Crucial Phase Rebirth of Ideals Memory Blackouts New Circle of Stable Friends Increase New Interest Develop Decrease of Ability to Stop Family & Friends Drinking/Drugging When Appreciate Effort Others Do So Adjustment to Family Drinking Bolstered with Needs Excuses Natural Rest and Sleep Grandiose and Desire to Escape Goes Aggressive Behavior Realistic Thinking Persistent Remorse Return of Self Esteem Efforts to Control Fail Regular Nourishment Taken Repeatedly Diminishing Fears of Promises and Resolutions Unknown Future Fail Appreciation of Possibilities Tries Geographic Escapes of New Way of Life Loss of Other Interest Start of Group Therapy Family and Friends Avoided Onset of New Hope Work and Money Physical Overhaul by Troubles Doctor Unreasonable Spiritual Needs Examined Resentments -

Alcohol Basics Training Overview

ALCOHOL BASICS TRAINING OVERVIEW This training is intended to help make students aware of Virginia law, common myths about alcohol and how to make healthy and responsible decisions. ( LEARNING OBJECTIVES: • To understand the risks and harms commonly associated with alcohol • To understand how to make safe and healthy decisions around alcohol • To recognize alcohol poisoning and know how to respond • To build confidence to identify risky situations and intervene when needed 3 HEADS UP RESOURCES: • Alcohol Education Basics Guide: This guide provides the relevant background information needed to present the Alcohol Basics Training. • Alcohol Basics Training PowerPoint • Alcohol Basics Training Script: The script provides the suggested content for each slide, however adapting the presentation of the content to meet your audience’s needs is highly recommended. • College Publication: We suggest handing these out before or after the training as a reinforcement of the information presented. • 21 and Older Publication: We suggest handing these out before or after the training as a reinforcement of the information presented. • HEADS UP Trivia Cards: If you have a larger group of students, integrating the trivia cards can help keep your training interactive. • HEADS UP Videos: Playing one or all of our videos during the training can help emphasize the content for students who may be visual learners. • HEADS UP Promotional Materials: Use our promotional materials as prizes if students answer a question correctly or hand out to all students at the end of the training. ALCOHOL BASICS TRAINING OVERVIEW W TIPS: • If you’re using the HEADS UP Trivia Cards, make it into a game and split your group of students into teams! • Be creative! Make the dialogue for each slide interactive to keep your audience engaged throughout the presentation. -

PREFERENCE for and TOLERANCE to ETHANOL: ACETALDEHYDE INVOLVEMENT by Helene Belanger-Grou

PREFERENCE FOR AND TOLERANCE TO ETHANOL: ACETALDEHYDE INVOLVEMENT by Helene Belanger-Grou A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Department of Psychology McGill University Montreal, Quebec, Canada ~ March 1984 • ABSTRACT A study was made to investigate the physiological bases of, and the relation between initial tolerance, development of tolerance and preference for ethanol in a strain of rats originally bred to accentuate differences in learning. Two major studies were conducted using 356 male and female rats of the and Tryon strain. Strain and sex related s1 s3 differential preference for ethanol was demonstrated. Tolerance to ethanol, measured by latency ol- ~nd sleep duration resulting from the administration of a soporific dose of ethanol, was lesser in the high-preference (51 >than in the low-preference (53 ) strain. Metabolic factors accounted for the lesser resistance to the anaesthetic effects of ethanol in 51 animals. In contrast, tolerance to ethanol, measured by the debilitating effect of a subhypnotic dose of ethanol on a previously learned motor task, was greater in the 5 1 (high-preference) than in the 53 \low-preference) rat.c·~. Development of behavioral tolerance on repeated exposure to ethanol occurred at a similar rate for s1 and 53 animals. Nonetheless 51 animals exhibited a greater neural tolerance in the course of tolerance development than their 53 counterparts. These findings led to the suggestion that preference for and initial tolerance to a subhypnotic dose of ethanol are related to and determined by inherent enzyme patterns that characterize the 5 and 5 lines of the 1 3 Tryon strain.