Long-Standing Hiccup in a Patient with Sarcoidosis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diaphragmatic Dysfunction Associates with Dyspnoea, Fatigue

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Diaphragmatic dysfunction associates with dyspnoea, fatigue, and hiccup in haemodialysis patients: a cross-sectional study Bin Wang1,5, Qing Yin1,5, Ying-yan Wang2,5, Yan Tu1, Yuchen Han1, Min Gao1, Mingming Pan1, Yan Yang1, Yufang Xue1, Li Zhang1, Liuping Zhang1, Hong Liu1, Rining Tang1, Xiaoliang Zhang1, Jingjie xiao3, Xiaonan H. Wang4 & Bi-Cheng Liu1* Muscle wasting is associated with increased mortality and morbidity in chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients, especially in the haemodialysis (HD) population. Nevertheless, little is known regarding diaphragm dysfunction in HD patients. We conducted a cross-sectional study at the Institute of Nephrology, Southeast University, involving 103 HD patients and 103 healthy volunteers as normal control. Ultrasonography was used to evaluate diaphragmatic function, including diaphragm thickness and excursion during quiet and deep breathing. HD patients showed lower end-inspiration thickness of the diaphragm at total lung capacity (0.386 ± 0.144 cm vs. 0.439 ± 0.134 cm, p < 0.01) and thickening fraction (TF) (0.838 ± 0.618 vs. 1.127 ± 0.757; p < 0.01) compared to controls. The velocity and excursion of the diaphragm were signifcantly lower in the HD patients during deep breathing (3.686 ± 1.567 cm/s vs. 4.410 ± 1.720 cm/s, p < 0.01; 5.290 ± 2.048 cm vs. 7.232 ± 2.365 cm; p < 0.05). Changes in diaphragm displacement from quiet breathing to deep breathing (△m) were lower in HD patients than in controls (2.608 ± 1.630 vs. 4.628 ± 2.110 cm; p < 0.01). After multivariate adjustment, diaphragmatic excursion during deep breathing was associated with haemoglobin level (regression coefcient = 0.022; p < 0.01). -

Intractable Hiccups Post Stroke: Case Report and Review of the Literature

logy & N ro eu u r e o N p h f y o s l i a o l n o Ferdinand and Oke, J Neurol Neurophysiol 2012, 3:5 r g u y o J Journal of Neurology & Neurophysiology ISSN: 2155-9562 DOI: 10.4172/2155-9562.1000140 CaseResearch Report Article OpenOpen Access Access Intractable Hiccups Post Stroke: Case Report and Review of the Literature Phillip Ferdinand* and Anthony Oke Department of Geriatrics and Stroke Medicine, Mid- Staffordshire NHS Trust, Stafford, UK Introduction several admissions for dehydration secondary to this. He was notably depressed and tearful at this meeting and felt his quality of life was very Intractable hiccups are uncommon but important sequelae in poor during hiccup bouts. Baclofen 5 mg tds was commenced and later the aftermath of ischaemic stroke. We present the case of a 50 year titrated up to 10 mg tds. Over the following 12 months he was trialled old gentleman, who developed what we believe to be the first case of on pregabalin (max dose 150 mg twice daily), Nifedipine (5 mg tds) intractable hiccups secondary to cerebellar infarction. The hiccups whilst levomepromazine, dexamethasone and ondansetron were used were refractory to wide range of single pharmaceutical and surgical for their anti-emetic properties. interventions and we eventually found some success with dual pharmaceutical therapy. Intractable hiccups can have a significant 18 months post discharged he was referred to a neurosurgeon. It impact on post stroke rehabilitation and have a considerable was agreed that on account of the fact he had failed multiple medical detrimental impact on an individual’s quality of life. -

Healthy Preterm Infant Responses to Taped Maternal Voice

J Perinat Neonat Nurs CONTINUING EDUCATION Vol. 22, No. 4, pp. 307–316 Copyright c 2008 Wolters Kluwer Health | Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Healthy Preterm Infant Responses to Taped Maternal Voice Maryann Bozzette, PhD, RN This study was a repeated measures design, examining behavioral and physiologic responses of premature infants to taped maternal voice. Fourteen stable, premature infants, 31 to 34 weeks’ gestation and serving as their own controls, were monitored and videotaped 4 times each day for 3 consecutive days during the first week of their life. There were no significant differences found in heart rate or oxygen saturation between study conditions. Behavioral data revealed less motor activity and more wakefulness, while hearing the maternal tape, suggesting some influence on infant state regulation. Attending behaviors were significantly greater, with more eye brightening and facial tone. Minimal distress was seen throughout the study, as indicated by stable heart rate and oxygen saturation and by the absence of behaviors such as jitteriness, loss of tone, or loss of color. The results of this preliminary study suggest that premature infants are capable of attending to tape recordings of their mother’s voice. Key words: infant stimulation, parent-infant relations, premature infants ost newborn infants are in close physical con- ture infants in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). Mtact with their mothers, and the rhythmic stim- Nevertheless, the potential for a mother’s voice to off- ulation of movement and intermittent speech experi- set overstimulating sensory input in the NICU and to enced during fetal development continues after birth. soothe a premature infant remains a relatively unex- The mother’s regulatory role for system organization plored area of research. -

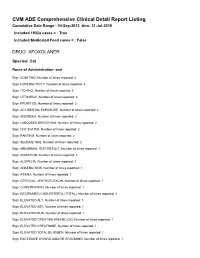

FDA CVM Comprehensive ADE Report Listing for Afoxolaner

CVM ADE Comprehensive Clinical Detail Report Listing Cumulative Date Range : 04-Sep-2013 -thru- 31-Jul-2018 Included 1932a cases = : True Included Medicated Feed cases = : False DRUG: AFOXOLANER Species: Cat Route of Administration: oral Sign: VOMITING, Number of times reported: 4 Sign: HYPERACTIVITY, Number of times reported: 3 Sign: ITCHING, Number of times reported: 3 Sign: LETHARGY, Number of times reported: 3 Sign: PRURITUS, Number of times reported: 3 Sign: ACCIDENTAL EXPOSURE, Number of times reported: 2 Sign: ANOREXIA, Number of times reported: 2 Sign: LABOURED BREATHING, Number of times reported: 2 Sign: NOT EATING, Number of times reported: 2 Sign: PANTING, Number of times reported: 2 Sign: SEIZURE NOS, Number of times reported: 2 Sign: ABNORMAL TEST RESULT, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: AGITATION, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ALOPECIA, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ANAEMIA NOS, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ATAXIA, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: CERVICAL VENTROFLEXION, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: CONSTIPATION, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: DECREASED CHOLESTEROL (TOTAL), Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ELEVATED ALT, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ELEVATED AST, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ELEVATED BUN, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ELEVATED CREATINE-KINASE (CK), Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ELEVATED CREATININE, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ELEVATED TOTAL BILIRUBIN, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: EXCESSIVE LICKING AND/OR GROOMING, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: FEVER, -

The Leakey Foundation |

Origin Stories Episode 2 Why Do We Get Hiccups? June 8, 2016 Origin Stories Episode 2: Why Do We Get Hiccups? June 8, 2016 Meredith Johnson 0:00:04 This is Origin Stories, the Leakey Foundation podcast. I’m Meredith Johnson. Today’s story is from producer, Ben Nimkin and it’s about something we’ve all experienced, but don’t usually think much about. Hi, Ben. Ben Nimkin Hey, Meredith. Meredith Johnson So, why hiccups? Ben Nimkin Yeah. So, my girlfriend, Anna, pretty much always gets the hiccups when she goes outside on a winter day. Page 1 Origin Stories Episode 2 Why Do We Get Hiccups? June 8, 2016 Meredith Johnson That’s pretty weird. Ben Nimkin I know, right? And they totally drive her crazy, because hiccups are annoying and they’re also super wacky and they don’t seem to serve any purpose. And it got me thinking—you know—there’s something else going on here. You know, there needs to be some reason for humans to have hiccups. Meredith Johnson And it turns out there is a reason—an ancient reason. There’s a lot more to the hiccup than you think. For most of us, it’s a temporary annoyance, gone in a few minutes. But some people aren’t so lucky. Ben Nimkin Charles Osborne was a farmer living in Iowa, 28 years old, 5’4” tall, and pretty muscular. And one day in 1922, he was feeling pretty sure of himself and he lifted up a 350-pound pig for slaughter, but the pig got the best of him and he fell to the ground. -

Sops) Sinovac Vaccine (Coronavac

Date: 21April 2021 Document Code: 63-01 Version: 01 Guidelines and Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) Sinovac Vaccine (CoronaVac) 1 Target Audience • All the concerned national, provincial & district health authorities and health care workers who are involved in the COVID-19 vaccine operations, establishment, and management of COVID-19 Vaccination Counters both at public and private health facilities. Objective of this document • To provide guidance on Sinovac COVID-19 Vaccine (CoronaVac) storage, handling, administration and safe disposal along with recommendations for vaccine recipients. Vaccination should not be considered as an alternate for wearing a mask, physical distancing and observing other SOPs for COVID-19 prevention. Vaccine Basic Information • CoronaVac manufactured by Sinovac Biotech Ltd. is an inactivated virus COVID-19 vaccine. • Active ingredient: Inactivated SARS-CoV-2 Virus (CZ02 strain). • Adjuvant: Aluminum hydroxide. • Excipients: Disodium hydrogen phosphate dodecahydrate, sodium dihydrogen phosphate monohydrate, sodium chloride. • CoronaVac is a milky-white suspension. Stratified precipitate may form which can be dispersed by shaking. Vaccine Dose • Two doses should be administered by intramuscular injection in the deltoid region of the upper arm. • The second dose is preferably given 28 days after the first dose. • Each vial (syringe) contains 0.5 mL of single dose containing 600S8U of inactivated SARS-CoV-2 virus as antigen. Who should receive CoronaVac: • Individuals who are above 18 years of age. Who should NOT receive CoronaVac: • Individuals who are below 18 years of age. The safety and efficacy of CoronaVac in children and adolescents below 18 have yet to be established. • People with history of allergic reaction to CoronaVac or other inactivated vaccine, or any component of CoronaVac (active or inactive ingredients, or any material used in the process). -

Resmed Origins Contents

ResMed Origins Contents Foreword 2 Preface 3 OSA in antiquity to 20th Century 5 Sleep research in the 20th Century 6 Professor Colin Edward Sullivan 9 Nasal CPAP 11 Dr Peter Craig Farrell 14 Baxter Centre for Medical Research 1986 - 1989 16 ResCare 1989 -1995 21 Epilogue 31 Treatments of OSA (other than CPAP) 33 Comorbidities 34 Awards ResMed group 35 Awards Dr Peter C Farrell 37 ResMed Patents issuing prior to IPO 37 Timeline of product introductions 38 ResCare staff 2 June 1995 40 References 41 ResCare Organisation Chart 43 Lancet 18 April 1981, pp 862-5 44 Endnotes 48 Photo Galleries 55 Foreword As is detailed later in this document, in 1981 Colin Sullivan and his colleagues introduced their invention of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. In my opinion, the only possible rival for a single product that would produce such an upturn in life expectation and quality of life for humanity was the introduction of penicillin. Although sleep specialists were aware that obstructive sleep apnea was a very serious illness and surprisingly commonplace, it would be more than a decade after the introduction of CPAP before the true and stunningly high prevalence would be documented by Terry Young and her colleagues. Rarely in the history of medicine has an eff ective treatment for an illness been developed before the true magnitude of the problem was scientifi cally established. The next big challenge after 1981 was to convert the Colin Sullivan vacuum cleaner device into a practical, eff ective, and dependable treatment for the literally millions of apnea victims around the world. -

Persistent Periodic Hiccups Following Brain Abscess: a Case Report

Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 1990;53:83-84 83 J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.53.1.83 on 1 January 1990. Downloaded from SHORT REPORT Persistent periodic hiccups following brain abscess: a case report P H P Jansen, E M G Joosten, H M Vingerhoets Abstract Recovery from this illness was incomplete A case is reported of a patient with and the patient was discharged from his job as periodic persistent hiccups and secon- medically unfit. His seizures were rare and dary generalised epilepsy lasting for a mostly provoked by stress. period of five years following a right Six months later the patient was woken at temporal brain abscess. The recurring night by rapid hiccups with a frequency of 30 episodes of hiccups had a ten day rhyth- per minute, which continued during his sleep. micity and unlike epileptic convulsions The bouts of hiccuping invariably lasted be- were unresponsive to treatment. tween 9-5 and 10-5 days and nights, alternating with 9-5-10-5 hiccup-free days and nights. Single precise and ryhthmic hiccup-sounds Hiccuping is one of the first movements of the could be heard, accompanied by abrupt human embryo and starts in the eighth week of movements of the respiratory musculature. gestation. Their purpose is unclear. Hiccups These were independent of respiratory cycle, may represent a vestigial element of a primitive respiratory rate and time of day. Fluoroscopy reflex, the significance of which is now lost. showed that the diaphragmatic movements Alternatively, it may represent an early res- were bilateral. -

Hiccups in the Neuro-Critical Care Unit: a Symptom Less Studied?

www.jmri.org.in Brief Communication Hiccups in the Neuro-Critical Care Unit: A Symptom Less Studied? Charu Dutt Arora*1, Jaya Wanchoo1, Garima Khera1 Quick Access Code ABSTRACT Article Details Background: Hiccups (also referred to as “hiccoughs”) are usually a transient condition Date Received: 06/04/2017 that affects almost everyone in their lifetime. However, persistent and intractable Date Revised: 08/04/2017 hiccups are the types which are linked with unfavorable outcomes and can also result in Date Accepted: 09/04/2017 Date Published: 10/04/2017 respiratory alkalosis in intubated patients. There is no accurate estimate of the DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.495730 prevalance of hiccups in the patients admitted in the neuro-ICU. The most commonly Editor(s): Varshil Mehta witnessed hiccups in the neuro-ICU are intractable and neurogenic in nature. In this Reviewer(s): Shyam Vora communication, we discuss the strategy of respiratory care and pharmacological Krutarth Shah management of hiccups in an adult male post decompressive craniotomy in view of Author Affiliation unilateral basal ganglion bleed. He suffered from persistent hiccups and was managed conservatively with intravenous Metachlorpromide 10 mg on as and when needed (SOS) 1. Institute of Critical Care and basis. In conclusion, it seems that persistent and intractable hiccups as a risk factor for Anesthesia, Medanta - The ventilator-associated pneumonia in patients who are intubated and mechanically Medicity, Gurgaon, India. ventilated should be given due attention. We encourage clinical trials in this area of Corresponding Author critical care medicine and should also encourage more studies to analyse the effectiveness of non-pharmacological methods. -

53949-Laryngeal-Manifestations-Of-Intractable-Singultus.Pdf

Open Access Case Report DOI: 10.7759/cureus.13730 Laryngeal Manifestations of Intractable Singultus Jhon F. Martinez Paredes 1 , Chandler C. Thompson 1 , Amy L. Rutt 1 1. Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, USA Corresponding author: Jhon F. Martinez Paredes, [email protected] Abstract Hiccup is a common phenomenon experienced by almost everyone in life. Although the exact physiology of this phenomenon remains unknown, it is associated with multiple central and peripheral etiologic causes. Vocal fold granulomas are benign laryngeal lesions typically caused by iatrogenic trauma, voice misuse, or chronic irritation. We present, for the first time, an association between intractable hiccups and vocal fold granulomas with good response to acupuncture and voice therapy in a 62-year-old male patient. This is an important contribution to the literature as the first report describing the co-occurrence of these pathologies in the context of a patient with several treatment failures, including vagal nerve stimulator. Categories: Family/General Practice, Otolaryngology, Other Keywords: intractable hiccups, singultus, vocal fold, granuloma, larynx Introduction Hiccup is a common phenomenon experienced by almost everyone in life [1]. Nearly 4,000 hospitalizations a year in the United States can be attributed to this condition [2]. Singultus, derived from the Latin word “singult,” meaning “to catch one’s breath while sobbing,” is the medical term for hiccups [3]. It involves coordinated and involuntary contractions of the inspiratory muscles associated with a delayed and sudden closure of the glottis, which is responsible for the characteristic noise [1,4]. Some causes of hiccups related to the oropharynx and larynx are neck cysts, pharyngitis, laryngitis, esophagitis, esophageal lesions, and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) [5]. -

A Dictionary of Neurological Signs.Pdf

A DICTIONARY OF NEUROLOGICAL SIGNS THIRD EDITION A DICTIONARY OF NEUROLOGICAL SIGNS THIRD EDITION A.J. LARNER MA, MD, MRCP (UK), DHMSA Consultant Neurologist Walton Centre for Neurology and Neurosurgery, Liverpool Honorary Lecturer in Neuroscience, University of Liverpool Society of Apothecaries’ Honorary Lecturer in the History of Medicine, University of Liverpool Liverpool, U.K. 123 Andrew J. Larner MA MD MRCP (UK) DHMSA Walton Centre for Neurology & Neurosurgery Lower Lane L9 7LJ Liverpool, UK ISBN 978-1-4419-7094-7 e-ISBN 978-1-4419-7095-4 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-7095-4 Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London Library of Congress Control Number: 2010937226 © Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2001, 2006, 2011 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. While the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of going to press, neither the authors nor the editors nor the publisher can accept any legal responsibility for any errors or omissions that may be made. -

Case Report: Two Cases of Persistent Hiccups Complicating COVID-19

Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg., 104(5), 2021, pp. 1713–1715 doi:10.4269/ajtmh.21-0190 Copyright © 2021 by The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene Case Report: Two Cases of Persistent Hiccups Complicating COVID-19 Hande Ikitimur,1* Betul Borku Uysal,2 Barıs Ikitimur,3 Sefika Umihanic,4 Jasmina Smajic,5 Rahima Jahic,6 and Ayhan Olcay7 1Department of Pulmonary Diseases, Biruni University Medical Faculty, Istanbul, Turkey; 2Department of Internal Medicine, Biruni University Medical Faculty, Istanbul, Turkey; 3Department of Cardiology, Cerrahpasa School of Medicine, University-Cerrahpasa, Istanbul, Turkey; 4Department Oncology, Clinic for Pulmonary Disease, Tuzla, Bosnia and Herzegovina; 5Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation Clinic, Intensive Care Unit University Medical Center Tuzla, Tuzla, Bosnia and Herzegovina; 6Clinic for Infectious Diseases, Tuzla, Bosnia and Herzegovina; 7Department of Cardiology, Istanbul Aydın University, Istanbul, Turkey Abstract. Two cases are presented with coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19)-related hiccups: one during initial pre- sentation and one 10 days after COVID-19 diagnosis. Hiccups in both patients were resistant to treatment and responded only to chlorpromazine. COVID-19 patients may present with hiccups and also may have hiccups after treatment. Resistant hiccups without any underlying disease other than COVID-19 should be considered in association with COVID- 19 and may respond well to chlorpromazine. INTRODUCTION chest tightness, or shortness of breath. He arrived at the neurology department with a complaint of hiccups. His neu- Hiccups are familiar to everyone; they are repetitive con- rological examination and magnetic resonance images of the tractions of the diaphragm and the intercostal muscles. The head were normal. The patient was then referred to the internal fi classi cation of hiccups is based on their duration.