E-Cigarettes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transnational Tobacco Companies in Indonesia

The Indonesia Tobacco Market: Foreign Tobacco Company Growth Indonesia is the world’s third largest cigarette market by volume (excluding China) and there are approximately 57 million smokers in the country.2-3 According to one tobacco company, the Indonesia tobacco market consisting of hand-rolled kreteks, machine-rolled kreteks and white cigarettes was 270 billion sticks with a profit pool of RP 26.5 trillion ($2.95 billion USD) in 2010, an increase of 18% since 2007.1 Additionally, Indonesia’s cigarette retail volume and value are predicted to continue to grow consistently over the next five years.2 Indonesia’s growing cigarette market, large population, high smoking prevalence among men, and highly unregulated market, make the country an attractive business opportunity for international tobacco companies attempting to make up for falling profits in developed markets like the United States and Australia. The powerful presence and nature of transnational tobacco companies (TTCs) in Indonesia Source: BAT investor presentation1 increases the threat of the tobacco industry to public health because the companies’ competitive efforts to reach young consumers and female smokers ultimately increase smoking prevalence in markets where they operate. 4 Since 2005, the Indonesian market has shifted from being solely dominated by local manufacturers to a market where the number one, four and six spots are controlled by TTCs: Philip Morris International-owned Sampoerna, British American Tobacco-owned Bentoel, and KT&G-owned Trisakti respectively. In 2010, the combined market share of these three companies made up almost 40% of the Indonesian market.2 Leading local tobacco companies include Gudang Garam (number two), Djarum (number three) and Najorono Tobacco Indonesia (number five). -

I UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the DISTRICT OF

Case 1:99-cv-02496-PLF Document 6276 Filed 08/03/18 Page 1 of 59 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ____________________________________ UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, ) Plaintiff, ) Civil Action No. 99-CV-2496 (PLF) ) and ) ) CAMPAIGN FOR TOBACCO-FREE ) KIDS, et al., ) Plaintiff-Intervenors, ) ) v. ) ) PHILIP MORRIS USA INC., et al., ) Defendants. ) ) and ) ) ITG BRANDS, LLC, et al., ) Post-Judgment Parties ) Regarding Remedies ) PLAINTIFFS’ 2018 SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF ON RETAIL POINT OF SALE REMEDY TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ......................................................................................................... iv INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1 FACTUAL BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................... 5 I. The Deal between Cigarette Manufacturers and Retailers ............................................... 5 II. Benefits to Participating Retailers .................................................................................... 6 III. Manufacturers’ Contractual Control over Space for Cigarette Marketing and Promotional Displays ....................................................................................................... 8 A. The types of retail advertising and marketing space ........................................8 B. The manufacturers’ contractual authority over participating retailers’ space 10 1. The -

PM 12.31.2014 Form 10K Wrap (Incl F/S & MD&A)

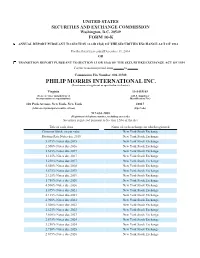

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2014 OR TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission File Number: 001-33708 PHILIP MORRIS INTERNATIONAL INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Virginia 13-3435103 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification No.) 120 Park Avenue, New York, New York 10017 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) 917-663-2000 (Registrant’s telephone number, including area code) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Name of each exchange on which registered Common Stock, no par value New York Stock Exchange Floating Rate Notes due 2015 New York Stock Exchange 5.875% Notes due 2015 New York Stock Exchange 2.500% Notes due 2016 New York Stock Exchange 1.625% Notes due 2017 New York Stock Exchange 1.125% Notes due 2017 New York Stock Exchange 1.250% Notes due 2017 New York Stock Exchange 5.650% Notes due 2018 New York Stock Exchange 1.875% Notes due 2019 New York Stock Exchange 2.125% Notes due 2019 New York Stock Exchange 1.750% Notes due 2020 New York Stock Exchange 4.500% Notes due 2020 New York Stock Exchange 1.875% Notes due 2021 New York Stock Exchange 4.125% Notes due 2021 New York Stock Exchange 2.900% Notes due 2021 New York Stock Exchange -

Subject: ACCEPTED FORM TYPE 10-K (0001193125-12-076983) Date: 24-Feb-2012 09:29

Subject: ACCEPTED FORM TYPE 10-K (0001193125-12-076983) Date: 24-Feb-2012 09:29 THE FOLLOWING SUBMISSION HAS BEEN ACCEPTED BY THE U.S. SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION. COMPANY: Philip Morris International Inc. FORM TYPE: 10-K NUMBER OF DOCUMENTS: 17 RECEIVED DATE: 24-Feb-2012 09:28 ACCEPTED DATE: 24-Feb-2012 09:29 FILING DATE: 24-Feb-2012 09:28 TEST FILING: NO CONFIRMING COPY: NO ACCESSION NUMBER: 0001193125-12-076983 FILE NUMBER(S): 1. 001-33708 THE PASSWORD FOR LOGIN CIK 0001193125 WILL EXPIRE 09-Feb-2013 13:14. PLEASE REFER TO THE ACCESSION NUMBER LISTED ABOVE FOR FUTURE INQUIRIES. REGISTRANT(S): 1. CIK: 0001413329 COMPANY: Philip Morris International Inc. ACCELERATED FILER STATUS: LARGE ACCELERATED FILER FORM TYPE: 10-K FILE NUMBER(S): 1. 001-33708 24-Feb-2012 09:29 Page 1 of 1 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K ⌧ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2011 OR TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission File Number: 001-33708 PHILIP MORRIS INTERNATIONAL INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Virginia 13-3435103 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification No.) 120 Park Avenue, New York, New York 10017 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) 917-663-2000 (Registrant’s telephone number, including area code) Securities registered -

Transforming Our Business

Transforming our business A cigarette manufacturing line (on the left-hand side) and a heated tobacco unit manufacturing line (on the right-hand side) at our factory in Neuchâtel, Switzerland Replacing cigarettes with While several attempts have been made to develop better alternatives to smoking, smoke-free products drawbacks in the technological capability of these products and a lack of consumer In 2017, PMI manufactured and shipped acceptance rendered them unsuccessful. 791 billion cigarettes and other Recent advances in science and combustible tobacco products and technology have made it possible to 36 billion smoke‑free products, reaching develop innovative products that approximately 150 million adult consumers consumers accept and that are less in more than 180 countries. harmful alternatives to continued smoking. Smoking cigarettes causes serious PMI has developed a portfolio of disease. Smokers are far more likely smoke‑free products, including heated Contribution of Smoke-Free than non‑smokers to get heart disease, tobacco products and nicotine‑containing Products to PMI’s Total lung cancer, emphysema, and other e‑vapor products that have the potential diseases. Smoking is addictive, and it Net Revenues to significantly reduce individual risk and 13% can be very difficult to stop. population harm compared to cigarettes. The best way to avoid the harms of Many stakeholders have asked us about smoking is never to start, or to quit. the role of these innovative smoke‑free But much more can be done to improve products in the context of our business the health and quality of life of those vision. Are these products an extension of who continue to use nicotine products, our cigarette product portfolio? Are they through science and innovation. -

Altria Group, Inc. Annual Report

Altria Group, Inc. 2019 Annual Report an Altria Company an Altria Company an Altria Company an Altria Company an Altria Company an Altria Company an Altria Company an Altria Company an Altria Company an Altria Company an Altria Company an Altria Company an Altria Company an Altria Company an Altria Company an Altria Company an Altria Company an Altria Company an Altria Company an Altria Company an Altria Company an Altria Company an Altria Company an Altria Company an Altria Company Howard A. Willard III Dear Fellow Shareholders Chairman of the Board and CEO Altria delivered solid performance in a dynamic year for the tobacco industry. Our core tobacco businesses delivered outstanding financial performance, and we made significant progress advancing our non-combustible product platform. We believe Altria’s enhanced business platform positions us well for future success. 2019 Highlights n Grew adjusted diluted earnings per share (EPS) by 5.8%, primarily driven by our core tobacco businesses; and types of legal cases pending against it, especially during the fourth n Achieved $600 million in annualized cost savings, exceeding our $575 quarter of the year. Altria recorded two impairment charges of our JUUL million target announced in December 2018; asset in 2019, reducing our investment to $4.2 billion at year-end, down from n Increased our regular quarterly dividend for the 54th time in 50 years $12.8 billion, our 2019 initial investment. JUUL remains the U.S. leader in the and paid shareholders approximately $6.1 billion in dividends; and e-vapor category, and in January 2020 we revised certain terms governing n Repurchased 16.5 million Altria shares for a total cost of $845 million. -

Altria Group, Inc. Annual Report

ananan Altria Altria Altria Company Company Company an Altria Company ananan Altria Altria Altria Company Company Company | Inc. Altria Group, Report 2020 Annual an Altria Company From tobacco company To tobacco harm reduction company ananan Altria Altria Altria Company Company Company an Altria Company ananan Altria Altria Altria Company Company Company an Altria Company Altria Group, Inc. Altria Group, Inc. | 6601 W. Broad Street | Richmond, VA 23230-1723 | altria.com 2020 Annual Report Altria 2020 Annual Report | Andra Design Studio | Tuesday, February 2, 2021 9:00am Altria 2020 Annual Report | Andra Design Studio | Tuesday, February 2, 2021 9:00am Dear Fellow Shareholders March 11, 2021 Altria delivered outstanding results in 2020 and made steady progress toward our 10-Year Vision (Vision) despite the many challenges we faced. Our tobacco businesses were resilient and our employees rose to the challenge together to navigate the COVID-19 pandemic, political and social unrest, and an uncertain economic outlook. Altria’s full-year adjusted diluted earnings per share (EPS) grew 3.6% driven primarily by strong performance of our tobacco businesses, and we increased our dividend for the 55th time in 51 years. Moving Beyond Smoking: Progress Toward Our 10-Year Vision Building on our long history of industry leadership, our Vision is to responsibly lead the transition of adult smokers to a non-combustible future. Altria is Moving Beyond Smoking and leading the way by taking actions to transition millions to potentially less harmful choices — a substantial opportunity for adult tobacco consumers 21+, Altria’s businesses, and society. To achieve our Vision, we are building a deep understanding of evolving adult tobacco consumer preferences, expanding awareness and availability of our non-combustible portfolio, and, when authorized by FDA, educating adult smokers about the benefits of switching to alternative products. -

Temporary Compliance Waiver Notice the Linked Files May Not Be Fully Accessible to Readers Using Assistive Technology

Temporary Compliance Waiver Notice The linked files may not be fully accessible to readers using assistive technology. We regret any inconvenience that this may cause our readers. In the event you are unable to read the documents or portions thereof, please email [email protected] or call 1-877-287-1373. Philip Morris Products S.A. THS Page 1 PMI Research & Development 2.7 Executive Summary MRTPA Section 2.7 Executive Summary Confidentiality Statement Confidentiality Statement: Data and information contained in this document are considered to constitute trade secrets and confidential commercial information, and the legal protections provided to such trade secrets and confidential information are hereby claimed under the applicable provisions of United States law. No part of this document may be publicly disclosed without the written consent of Philip Morris International. Philip Morris Products S.A. THS Page 2 PMI Research & Development 2.7 Executive Summary TABLE OF CONTENTS 2.7.1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .....................................................................................9 2.7.2 PROPOSED MODIFIED RISK AND MODIFIED EXPOSURE CLAIMS ........15 2.7.3 MODIFIED RISK TOBACCO PRODUCTS AND HARM REDUCTION .........17 2.7.4 PRODUCT DESCRIPTION AND SCIENTIFIC RATIONALE ..........................19 Development Rationale and Product Description for THS ............................................19 Heating Instead of Burning Reduces Harmful Constituents ......................................19 Product Description ...................................................................................................20 -

Complete Annual Report

Philip Morris International 2016 Annual Report THIS CHANGES EVERYTHING 2016 Philip Morris Annual Report_LCC/ANC Review Copy February 22 - Layout 2 We’ve built the world’s most successful cigarette company with the world’s most popular and iconic brands. Now we’ve made a dramatic decision. We’ve started building PMI’s future on breakthrough smoke-free products that are a much better choice than cigarette smoking. We’re investing to make these products the Philip Morris icons of the future. In these changing times, we’ve set a new course for the company. We’re going to lead a full-scale effort to ensure that smoke- free products replace cigarettes to the benefit of adult smokers, society, our company and our shareholders. Reduced-Risk Products - Our Product Platforms Heated Tobacco Products Products Without Tobacco Platform Platform 1 3 IQOS, using the consumables Platform 3 is based on HeatSticks or HEETS, acquired technology that features an electronic holder uses a chemical process to that heats tobacco rather Platform create a nicotine-containing than burning it, thereby 2 vapor. We are exploring two Platform creating a nicotine-containing routes for this platform: one 4 vapor with significantly fewer TEEPS uses a pressed with electronics and one harmful toxicants compared to carbon heat source that, once without. A city launch of the Products under this platform cigarette smoke. ignited, heats the tobacco product is planned in 2017. are e-vapor products – without burning it, to generate battery-powered devices a nicotine-containing vapor that produce an aerosol by with a reduction in harmful vaporizing a nicotine solution. -

Sales -- Implied Warranty -- Cigarette Manufacturer's Liability for Lung Cancer Henry S

NORTH CAROLINA LAW REVIEW Volume 42 | Number 2 Article 18 2-1-1964 Sales -- Implied Warranty -- Cigarette Manufacturer's Liability for Lung Cancer Henry S. Manning Jr. Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/nclr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Henry S. Manning Jr., Sales -- Implied Warranty -- Cigarette Manufacturer's Liability for Lung Cancer, 42 N.C. L. Rev. 468 (1964). Available at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/nclr/vol42/iss2/18 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Law Review by an authorized editor of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NORTH CAROLINA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 42 lingering, ominous cloud of illegality under the Robinson-Patman Act. JAMES M. TALLEY, JR. Sales-Implied Warranty-Cigarette Manufacturer's Liability for Lung Cancer Plaintiff's decedent initiated suit in the United States District Court for the Southern District of Florida to recover damages for personal injuries resulting from lung cancer allegedly incurred by smoking Lucky Strike cigarettes. Shortly thereafter, he died from this condition and this claim1 was consolidated with another brought under the Florida wrongful death statute.' The district court sub- mitted the case to the jury on theories of negligence and breach of implied warranty.' In addition to rendering a general verdict for defendant, the jury answered specific interrogatories4 to the effect that the fatal lung cancer was proximately caused by the smoking of Lucky Strikes and that, as of the time of the discovery of the cancer, defendant could not by the reasonable application of human skill and foresight have known of the danger to users of his product. -

Hong Kong: Marlboro Tries It on (The Pack) Italy

Tobacco Control 2002;11:171–175 Tob Control: first published as 10.1136/tc.11.3.171 on 1 September 2002. Downloaded from Newsanalysis................................................................................ Hong Kong: than pocket sized mini-billboards. circumstances—occupation (teacher), Apart from the health warning, each genetic background, living con- Marlboro tries it on large face was largely covered in ditions—the panel concluded that the images of that universal symbol of disease was at least 80% attributable (the pack) independence who shores up the to smoking. Whenever a government announces morale of PM’s nicotine captives. Building on the traditional approach tobacco control measures which to- Reports from Hong Kong suggest to toxic torts, the panel tried to find bacco companies suspect will be effec- this was a classic trial run. Will they the fingerprint of carcinogens of tive, the companies’ first reaction, at get away with it? They did that time, it tobacco smoke. According to the best least in private, is to work out ways of seems. Will they be back? And if they forensic evidence, these can now be getting round them. Under self regula- can get away with it in Hong Kong, found in the genes of the victim, tion, they implement whatever will they try it elsewhere? Make sure contained in the victim’s cells collected and preserved at the time of hospital schemes they think will most com- your legislation is tightly drafted, then administration. More specifically, re- pletely negate the measures they have sit back and watch this space. just agreed to, and continue for as long cent scientific literature suggests that as they can get away with it. -

EU Tobacco Products Directive 2014/40/EC

29.4.2014 EN Official Journal of the European Union L 127/1 I (Legislative acts) DIRECTIVES DIRECTIVE 2014/40/EU OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 3 April 2014 on the approximation of the laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the Member States concerning the manufacture, presentation and sale of tobacco and related products and repealing Directive 2001/37/EC (Text with EEA relevance) THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, Having regard to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, and in particular Articles 53(1), 62 and 114 thereof, Having regard to the proposal from the European Commission, After transmission of the draft legislative act to the national parliaments, Having regard to the opinion of the European Economic and Social Committee ( 1 ), Having regard to the opinion of the Committee of the Regions ( 2), Acting in accordance with the ordinary legislative procedure ( 3 ), Whereas: (1) Directive 2001/37/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council ( 4) lays down rules at Union level concerning tobacco products. In order to reflect scientific, market and international developments, substantial changes to that Directive would be needed and it should therefore be repealed and replaced by a new Directive. (2) In its reports of 2005 and 2007 on the application of Directive 2001/37/EC the Commission identified areas in which further action was considered useful for the smooth functioning of the internal market. In 2008 and 2010 the Scientific Committee on Emerging and Newly Identified Health Risks (SCENIHR) provided scientific advice to the Commission on smokeless tobacco products and tobacco additives.