New Insights Into Secondary Prevention in Post-Traumatic Stress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction: Exploring the Boundaries of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

Introduction Introduction Exploring the Boundaries of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Other Anxiety Disorders Eric Hollander, M.D.; Joseph Zohar, M.D.; and Donatella Marazziti, M.D. Chairs of the International Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Conference Organizing and Scientific Committee © Copyright 2002 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc. he Fifth International Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Conference (5th IOCDC) took Tplace March 29 to April 1, 2001, in the spectacular setting of Sardinia, Italy. This supplement, “Exploring the Boundaries of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Other Anx- iety Disorders: New Developments and Practical Approaches,” is an outgrowth and testa- ment to this exciting meeting and process. The IOCDC has been a premier ongoing series of meetings in the OCD field, bringing together international experts in selected topics of interest to OCD and related disorders. Various research initiatives,One personal such as the copy International may be Treatment-Refractoryprinted OCD Consor- tium and the International OCD Genetics Consortium, have been outgrowths of, and were facilitated by, this process. The 5th IOCDC focused on social anxiety disorder and general- ized anxiety disorder, as well as OCD. These meetings have been generously supported by an unrestricted educational grant from Solvay Pharmaceuticals. This supplement to The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry begins with an article by Nestadt and colleagues on defining the phenotype of OCD, which is essential for genetic and treat- ment studies of this syndrome. The authors describe a family-study approach that further validates the hypothesis that the phenotypic spectrum of OCD is relatively broad, including body dysmorphic disorder, hypochondriasis, and the grooming disorders as a group. This approach may also lead to the identification of more homogeneous subgroups within OCD. -

Serotonin-1D Hypothesis of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: an Update

Zohar et al. Serotonin-1D Hypothesis of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: An Update Joseph Zohar, M.D.; James L. Kennedy, M.D.; Eric Hollander, M.D.; and Lorrin M. Koran, M.D. Support for the serotonin-1D (5-HT1D) hypothesis of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and related conditions comes from a variety of sources. Some pharmacologic challenges with the 5-HT1D ago- nist sumatriptan, and case reports in which prolonged administration of 5-HT1D agonists was associated with a therapeutic effect, suggest that 5-HT1D may play a role in obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Ge- netic studies have also found that polymorphism of the 5-HT1D gene may be preferentially transmitted to those patients with OCD. However, taking into account that OCD is a heterogeneous syndrome, the 5-HT1D hypothesis requires further investigation in order to disentangle the role of the 5-HT1D receptor in this common and often severe disorder. (J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65[suppl 14]:18–21) he pathophysiology of most mental disorders has symptom changes following administration of lactate,7 T yet to be elucidated. One way to study pathophysi- carbon dioxide,8 yohimbine,9 and cholecystokinin receptor ology is by specific activation of the system or receptor(s) agonists10 suggests that OCD patients are not sensitive to hypothesized to be relevant, i.e., pharmacologic challenge. all anxiogenic challenges and that the serotonergic compo- A pharmacologic challenge is designed to induce a set nent of the m-CPP challenge may play a critical role in the of specific and relevant symptoms (e.g., exacerbation of pathology of OCD. -

Joseph Zohar

Joseph Zohar Joseph Zohar is director of psychiatry A and director of the Anxiety and Obsessive Compulsive Clinic at the Sheba Medical Center at Tel Hashomer in Israel. He graduated from Tel Aviv University Sackler School of Medicine in 1973, trained in psychiatry at the University of Washington, Seattle, and at the Jerusalem Mental Health Center in Israel, where he was the director of the Resistant Depression Unit. In 1984, he joined the laboratory of Dennis Murphy at the National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, Maryland, where he was acting director of the Obsessive-Compulsive Clinic. In 1986 he served as chairman of the panel for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder of the American Psychiatric Association Task Force on Treatments of Psychiatric Disorders, and in 1989 as a member of the DSM-IV Obsessive Compulsive subcommittee. In 1992, Joseph Zohar established the International Council on Anxiety and OCD that is currently entitled World Council on Anxiety, and in 1993 he was nominated as the chairman of the anxiety and OCD section of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA) along with his role as the chairperson of the World Council on Anxiety. In 1994 he was the chairman of the 7th meeting of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology (ECNP) and in 1995 was elected as a member of the executive committee of the College and chairman of the Israel Society for Biological Psychiatry. In 1996 he was nominated as a member of the WHO Expert Advisory Panel on Neuroscience. In 1997 he was elected to the executive committee of the World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry. -

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, Second Edition (WPA Series In

VOLUME 4 Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Second Edition Edited by Mario Maj University of Naples, Italy Norman Sartorius University of Geneva, Switzerland Ahmed Okasha Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt Joseph Zohar Tel Aviv University, Israel WPA Series Evidence and Experience in Psychiatry VOLUME 4 Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Second Edition WPA Series Evidence and Experience in Psychiatry Other Titles in the WPA Series Evidence and Experience in Psychiatry Volume 1ÐDepressive Disorders, Second Edition Mario Maj and Norman Sartorius Volume 2ÐSchizophrenia, Second Edition Mario Maj and Norman Sartorius Volume 3ÐDementia, Second Edition Mario Maj and Norman Sartorius Volume 5ÐBipolar Disorder Mario Maj, Hagop S. Akiskal, Juan Jose LoÂpez-Ibor and Norman Sartorius VOLUME 4 Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Second Edition Edited by Mario Maj University of Naples, Italy Norman Sartorius University of Geneva, Switzerland Ahmed Okasha Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt Joseph Zohar Tel Aviv University, Israel WPA Series Evidence and Experience in Psychiatry Copyright # 2002 John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex PO19 8SQ, England Telephone (+44) 1243 779777 Email (for orders and customer service enquiries): [email protected] Visit our Home Page on www.wileyeurope.com or www.wiley.com First Edition printed in 2000. All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except under the terms of the Copyright, Designs and Patients Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP, UK, without the permission in writing of the Publisher. -

Guidelines for the Pharmacological Treatment of Anxiety Disorders, Obsessive– Compulsive Disorder and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Primary Care

International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice, 2012; 16: 77–84 REVIEW ARTICLE Guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of anxiety disorders, obsessive – compulsive disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder in primary care BORWIN BANDELOW 1 , LEO SHER 2 , ROBERTAS BUNEVICIUS 3 , ERIC HOLLANDER 2 , SIEGFRIED KASPER 4 , JOSEPH ZOHAR 5 , HANS-J Ü RGEN M Ö LLER 6 , WFSBP TASK FORCE ON MENTAL DISORDERS IN PRIMARY CARE a AND WFSBP TASK FORCE ON ANXIETY DISORDERS , OCD AND PTSD b 1 Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University of G ö ttingen, Gö ttingen, Germany, 2 Albert Einstein College of Medicine and Montefi ore Medical Center, New York City, NY, USA, 3 Institute of Psychophysiology and Rehabilitation, Lithuanian University of Health Sciences, Palanga, Lithuania, 4 Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria, 5 Division of Psychiatry, Chaim-Sheba Medical Center, Tel-Hashomer, Ramat Gan, Israel, and 6 Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Ludwig Maximilian University, Munich, Germany Abstract Objective. Anxiety disorders are frequently under-diagnosed conditions in primary care, although they can be managed effectively by general practitioners. Methods. This paper is a short and practical summary of the World Federation of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of anxiety disorders, obsessive– compulsive disorder (OCD) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) for the treatment in primary care. The recommendations were developed by a task force of 30 international experts in the fi eld and are based on randomized controlled studies. Results. First-line pharmacological treatments for these disorders are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (for all disor- ders), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (for some) and pregabalin (for generalized anxiety disorder only). -

Comparison of Criminal Activity Between Israeli Veterans with and Without PTSD

Sherman, S., Fostick, L. , Zohar, J. (accepted). Comparison of Criminal Activity between Israeli Veterans with and Without PTSD. Depression and Anxiety . ***This is a self-archiving copy and does not fully replicate the published version*** Comparison of Criminal Activity between Israeli Veterans with and Without PTSD Shany Sherman *1 , Leah Fostick *2 , Joseph Zohar 1, 3 , on behalf of the Israeli Consortium on PTSD † 1 – Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel 2 – Ariel University, Ariel, Israel 3 – Department of Psychiatry, Chaim Sheba Medical Center, Tel Hashomer, Israel * - Shany Sherman and Leah Fostick are acknowledged to have made an equal contribution to the manuscript. † - The Israeli Consortium on PTSD includes: Zohar J(chair), Bleich A, Kaplan Z, Katz I, Klein E, Kotler M, Shalev AY, Ohry A, and Weissman Z. Address for correspondence: Dr. J. Zohar; Department of Psychiatry; Sheba Medical Center; Tel Hashomer; Israel. Telephone: 972-3530-3300. Fax: 972-3535-2788. Email: [email protected]. Zohar J has received grant/research support from Lundbeck, Servier and Pfizer, has served as a consultant or on advisory boards for Servier, Pfizer, Abbott, Actelion, AstraZeneca and Roche, and has served on speakers’ bureaus for Lundbeck, GSK, AstraZeneca and Abbott. ZOHAR JOSEPH This study was partially supported by a grant from the Rehabilitation Center of the Israeli Ministry of Defense. Key words Posttraumatic stress disorder; Veterans; Military; Violence; Criminal record 2 ZOHAR JOSEPH Abstract Background: The literature, based on US Vietnam veterans, suggests that PTSD is associated with increased criminal activity, especially violence, alcohol and drug abuse, although more recent studies, which tested data from the US as well as the UK, suggest a more moderate effect for this relationship. -

High Prevalence of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Among Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Patients

Nacasch, N., Fostick, L. , Zohar, J. (2011). High prevalence of obsessive-compulsive disorder among posttraumatic stress disorder patients. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 21, 876– 879. ***This is a self-archiving copy and does not fully replicate the published version*** High prevalence of obsessive -compulsive disorder among posttraumatic stress disorder patients Nitsa Nacasch 1, Leah Fostick 2, Joseph Zohar 1 1Division of Psychiatry, Chaim Sheba Medical Center, Tel Hashomer, 52621, Israel 2Ariel University Center, Ariel, 40700, Israel Corresponding author: Prof. J. Zohar, Department of Psychiatry; Sheba Medical Center; Tel Hashomer 52621; Israel. Telephone: 972-3530-3300. Fax: 972-3535-2788. Email: [email protected] High prevalence of obsessive compulsive disorder among posttraumatic stress disorder patients Posttraumatic obsessions have been reported in a few studies and case series. However, the magnitude of this phenomenon is still unknown. In the current study we systematically evaluated the prevalence of OCD in a sample of combat and terror related PTSD patients. Out of 44 referrals, 43% of the participants had PTSD with no OCD and 41% were diagnosed also with OCD. Six percent had sub-threshold OC symptoms. No difference was found between PTSD and PTSD-OCD participants' characteristics (including demographics, trauma-related factors, and other psychiatric co-morbidity). The surprisingly high number of OCD found in the current study suggests that PTSD-OCD might be underdiagnosed, signifies the importance of direct assessment -

Pharmacological Interventions for Preventing Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (Review)

Pharmacological interventions for preventing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Review) Amos T, Stein DJ, Ipser JC This is a reprint of a Cochrane review, prepared and maintained by The Cochrane Collaboration and published in The Cochrane Library 2014, Issue 7 http://www.thecochranelibrary.com Pharmacological interventions for preventing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Review) Copyright © 2014 The Cochrane Collaboration. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. TABLE OF CONTENTS HEADER....................................... 1 ABSTRACT ...................................... 1 PLAINLANGUAGESUMMARY . 2 SUMMARY OF FINDINGS FOR THE MAIN COMPARISON . ..... 4 BACKGROUND .................................... 6 OBJECTIVES ..................................... 7 METHODS ...................................... 7 RESULTS....................................... 13 Figure1. ..................................... 14 Figure2. ..................................... 17 Figure3. ..................................... 18 ADDITIONALSUMMARYOFFINDINGS . 23 DISCUSSION ..................................... 26 AUTHORS’CONCLUSIONS . 27 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . 28 REFERENCES ..................................... 28 CHARACTERISTICSOFSTUDIES . 33 DATAANDANALYSES. 56 Analysis 1.1. Comparison 1 Propranolol versus placebo, Outcome 1 Treatment efficacy. 56 Analysis 1.2. Comparison 1 Propranolol versus placebo, Outcome 2 Sensitivity analysis - observed cases. 57 Analysis 2.1. Comparison 2 Hydrocortisone versus placebo, Outcome 1 Treatment efficacy. 58 Analysis 2.2. Comparison -

PTSD Prevention with Escitalopram

Zohar, J., Fostick, L., Juven-Wetzler, A., Kaplan, Z., Shalev, H., Schreiber, G., Miroshnik, N., Shalev, A.Y., Stein, D., Suliman, S., Klein, E. (in press). Secondary Prevention of Chronic PTSD by Early and Short-Term Administration of Escitalopram: A Prospective Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind Trial. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. ***This is a self-archiving copy and does not fully replicate the published version*** Secondary prevention of chronic PTSD by early and short administration of esitalopram: a prospective randomized controlled double blind trial Joseph Zohar, MD1, Leah Fostick, PhD2, Alzabeta Juven-Wetzler, MD1, Zeev Kaplan, MD3, Hadar Shalev, MD4, Gavriel Schreiber, MD5,6, Natalie Miroshnik, MD5, Arieh Y. Shalev , MD7,8, Dan Stein, MD9, Sharain Suliman, PhD10, Ehud Klein, MD11 1 Department of Psychiatry, Chaim Sheba Medical Center, Tel-Hashomer, Israel 2 Department of Communication Disorders, Ariel University, Ariel, Israel 3 Beer-Sheva Mental Health Center, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beer-Sheva, Israel. 4 Soroka Medical Center, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beer-Sheva, Israel. 5 Department of Psychiatry, Barzilai Medical Center, Ashkelon, Israel 6 Department of Psychiatry, Faculty for Health Sciences, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beer Sheva, Israel 7 Department of Psychiatry, Hadassah University Hospital, Jerusalem, Israel 8 Department of Psychiatry, New York University Langone Medical Center, New York, NY 9 Department of Psychiatry & Mental Health, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa 10 Department of Psychiatry, Stellenbosch University, Cape Town, South Africa 11 Department of Psychiatry, Rambam Medical Health Center, Haifa, Israel Running title: PTSD prevention with SSRI 1 Corresponding author: Joseph Zohar, Department of Psychiatry, Chaim Sheba Medical Center, Tel Hashomer, Israel 52621 [email protected]. -

Currentp SYCHIATRY

Currentp SYCHIATRY Terror-related stress How ready are you to deal with it? Peter A. Kelly Theresa Fiore Lavery After the Sept. 11 attacks and the anthrax scare, psychiatrists are seeing exacerbated or recurrent PTSD in existing patients and trauma-related symptoms in new patients. In this special report from the editors, we offer clues to the differential diagnosis from comorbid disorders and suggestions that can help manage ongoing public fears. ince September 11, America has carried on under a 4. Managing fear in your communities—in response to the cloud of fear. Though the cloud is lifting, it will not Sept. 11 attacks, to the anthrax scare, or in anticipation S disappear for months or years. The terrorist attacks of an impending catastrophe. on New York City and Washington, DC, the resultant mili- To bring you this special report, the editors of Current tary action in Afghanistan, and the anthrax scare—combined Psychiatry have reviewed the literature and interviewed psy- with pervasive, nagging doubts about homeland security and chiatrists nationwide and in countries such as Israel and the specter of another possible future terrorist attack—all are Colombia, where terrorism has been a fact of life for years straining the nation’s collective emotional well-being. (see “PTSD lessons from Israel, Colombia,” page 33). Psychiatrists in America have reported new cases of ter- ror-inspired acute stress disorder, anxiety, depression, and Terror and your patients other illnesses, as well as recurrences of posttraumatic stress Which symptoms are you most likely to see in existing disorder (PTSD) in existing patients, in the weeks after the patients subsequent to recent events? In the weeks following recent attacks and the anthrax scare. -

Is PTSD-Phenotype Associated with HPA-Axis Sensitivity? Feedback Inhibition and Other Modulating Factors of Glucocorticoid Signaling Dynamics

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Is PTSD-Phenotype Associated with HPA-Axis Sensitivity? Feedback Inhibition and Other Modulating Factors of Glucocorticoid Signaling Dynamics Dor Danan 1, Doron Todder 1, Joseph Zohar 2 and Hagit Cohen 1,* 1 Anxiety and Stress Research Unit, Beer-Sheva Mental Health Center, Ministry of Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beer-Sheva 84170, Israel; [email protected] (D.D.); [email protected] (D.T.) 2 Post-Trauma Center, Sheba Medical Center, Tel Aviv 52621, Israel; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +972-544-369106 Abstract: Previously, we found that basal corticosterone pulsatility significantly impacts the vulner- ability for developing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Rats that exhibited PTSD-phenotype were characterized by blunted basal corticosterone pulsatility amplitude and a blunted corticosterone response to a stressor. This study sought to identify the mechanisms underlining both the loss of pulsatility and differences in downstream responses. Serial blood samples were collected manually via jugular vein cannula at 10-min intervals to evaluate suppression of corticosterone following methylprednisolone administration. The rats were exposed to predator scent stress (PSS) after 24 h, and behavioral responses were assessed 7 days post-exposure for retrospective classification into behavioral response groups. Brains were harvested for measurements of the glucocorticoid Citation: Danan, D.; Todder, D.; receptor, mineralocorticoid receptor, FK506-binding protein-51 and arginine vasopressin in specific Zohar, J.; Cohen, H. Is brain regions to assess changes in hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal axis (HPA) regulating factors. PTSD-Phenotype Associated with Methylprednisolone produced greater suppression of corticosterone in the PTSD-phenotype group. -

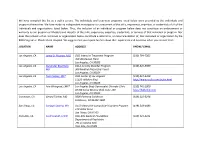

We Have Compiled This List As a Public Service. the Individuals and Treatment Programs Listed Below Were Provided by the Individuals and Programs Themselves

We have compiled this list as a public service. The individuals and treatment programs listed below were provided by the individuals and programs themselves. We have made no independent investigation or assessment of the skills, experience, expertise, or credentials of all of the individuals and organizations listed below. Thus, the inclusion of an individual or program below does not constitute an endorsement or warranty by our program or Rhode Island Hospital of the skills, experience, expertise, credentials, or services of that individual or program. Nor does the inclusion of an individual or organization below constitute a referral to, or recommendation of, that individual or organization by the BDD Program or Rhode Island Hospital. We suggest that you inquire further about their experience and expertise when you contact them. LOCATION NAME ADDRESS PHONE/ EMAIL Los Angeles, CA Jamie D. Feusner, M.D OCD Intensive Treatment Program (310) 794-7305 760 Westwood Plaza Los Angeles, CA 90095 Los Angeles, CA Alexander Bystritsky UCLA Anxiety Disorder Program (310) 825-9989 MD 300 Medical Plaza (2nd Floor) Los Angeles, CA 90024 Los Angeles, CA Tom Corboy, MFT OCD Center of Los Angeles (310) 824-5200 11620 Wilshire Blvd. http://www.ocdla.com/index.html Los Angeles, CA 90025 Los Angeles, CA Arie Winograd, LMFT Los Angeles Body Dysmorphic Disorder Clinic (310) 741-2000 10780 Santa Monica Blvd, Suite 120 http://bddclinic.com Los Angeles, CA 90025 Calabasas, CA Gerald Tarlow, MD 5000 Parkway Calabasas (818) 222-0294 Calabasas, CA 91302-1400 San Diego, CA Sanjaya Saxena, MD UCSD Obsessive-Compulsive Disorders Program (619) 543-6883 140 Arbor Drive San Diego, CA 92103 Palo Alto, CA Scott Granet, LCSW Palo Alto Medical Foundation (650) 321-4121 Department of Psychiatry 795 El Camino Real Palo Alto, CA 94301 Fort Lauderdale, FL Bruce M.