Prosecution in America a Historical and Comparative Account

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Way in Which Large Organisations Conduct Private Prosecutions; RSPCA

JUSTICE COMMITTEE, PRIVATE PROSECUTIONS BY ORGANISATONS BY MS.P. WALLWORK The way in which large organisations conduct private prosecutions; RSPCA Navigating the submission. Submission summary in bullet points page 2 POINT NUMBERS BELOW The RSPCA in a prosecution role, with the reasons it should not continue 1 – 36 Lawfulness of any RSPCA prosecution? 6 – 36 Role of the police, 37 – 43 Role of the RSPCA 44 – 85 A. Charitable status 44 -46 B. Prosecution lack of legal oversight 47 – 49 C. Crown Prosecution Service not involved 50 – 68 D. Lack of oversight by the courts 69 – 85 RSPCA double standards 86 – 91 RSPCA without police present and where police do not have a warrant 92 -105 RSPCA witness statements 106 – 115 RSPCA and the Courts 116 – 122 RSPCA and the legal profession 123 –125 RSPCA and the cost to the charity of a prosecution policy 126 – 129 Cost to the public from an RSPCA prosecution 130 – 135 RSPCA relationship with local authorities 136 – 144 Benefit to animal welfare 145 – 147 Cost to local authorities of implementing section 51 inspectors 148 -162 Proposals - page 30 Additional material in support of points made in the body of the submission Twenty ways to have your animals taken unlawfully page 32 RSPCA recruitment – demonstrating that ‘inspector’ level employees are unqualified to inspect animals. (Direct from RSPCA ) page 33. Wooler report page 35 RSPCA, firearms, and killing animals page 40 CASE FILES PAGE 44 - 57 end off submission. 1 JUSTICE COMMITTEE, PRIVATE PROSECUTIONS BY ORGANISATONS BY MS.P. WALLWORK The author of this submission. The writer of this document re ‘private prosecutions’ by organisations has been researching the subject of the RSPCA since 2015, including many cases in depth, having graduated with a law degree, completed examinations to become a solicitor, and lectured within a university setting to law undergraduates. -

Traffic Tickets-**ITHACA CITY COURT ONLY

The Ithaca City Prosecutor’s Office prosecutes traffic tickets within the City of Ithaca and as part of that responsibility also makes offers to resolve tickets in writing. Please note that written dispositions can only be accommodated in cases in which the charges do not involve misdemeanors. If you are charged with any misdemeanor, including Driving While Intoxicated or Aggravated Unlicensed Operation you must appear in person in Court. The following applies to traffic tickets in the City of Ithaca that are not misdemeanors. All questions about fines, penalties and rescheduling of court dates/appearances must be addressed to the Court. If you have an upcoming Court date on a traffic ticket, only the Court can excuse your appearance. If you fail to appear in Court, the Court can suspend your driver license. If you wish to request that an upcoming appearance be rescheduled to allow time to correspond with our office, you must contact the Court directly. Contact information for the Ithaca City Court can be found here How to Request an Offer to Resolve Your Traffic Ticket Pending in Ithaca City Court Due to the large volume of the traffic caseload we only respond to email requests. Please do not use mail, fax or phone calls to solicit an offer. Please do not contact the Tompkins County District Attorney, the Tompkins County Attorney, or the Ithaca City Attorney- only the Ithaca City prosecutor. To confirm that this is the correct court, check the bottom left of your ticket- it should state that the matter is scheduled for Ithaca City Court, 118 East Clinton Street. -

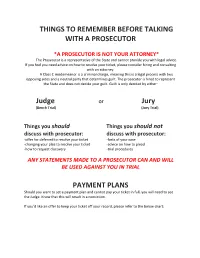

Things to Remember Before Talking with a Prosecutor

THINGS TO REMEMBER BEFORE TALKING WITH A PROSECUTOR *A PROSECUTOR IS NOT YOUR ATTORNEY* The Prosecutor is a representative of the State and cannot provide you with legal advice. If you feel you need advice on how to resolve your ticket, please consider hiring and consulting with an attorney. A Class C misdemeanor is a criminal charge, meaning this is a legal process with two opposing sides and a neutral party that determines guilt. The prosecutor is hired to represent the State and does not decide your guilt. Guilt is only decided by either: Judge or Jury (Bench Trial) (Jury Trial) Things you should Things you should not discuss with prosecutor: discuss with prosecutor: -offer for deferred to resolve your ticket -facts of your case -changing your plea to resolve your ticket -advice on how to plead -how to request discovery -trial procedures ANY STATEMENTS MADE TO A PROSECUTOR CAN AND WILL BE USED AGAINST YOU IN TRIAL PAYMENT PLANS Should you want to set a payment plan and cannot pay your ticket in full, you will need to see the Judge. Know that this will result in a conviction. If you’d like an offer to keep your ticket off your record, please refer to the below chart: How To Resolve Your Case With The Prosecutor Do you want an offer to pay for your ticket? YES NO Do you want to accept the offer No Set for trial that has been made? YES Do you need more time to save for the offer? YES NO Ask Judge for a Complete deferred continuance if you agreement and haven't had one. -

The American Prosecutor: Independence, Power, and the Threat of Tyranny

American University Washington College of Law Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law Articles in Law Reviews & Other Academic Journals Scholarship & Research 2001 The American Prosecutor: Independence, Power, and the Threat of Tyranny Angela J. Davis American University Washington College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/facsch_lawrev Part of the Administrative Law Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, Criminal Law Commons, Law and Politics Commons, and the Legal Profession Commons Recommended Citation Davis, Angela J., "The American Prosecutor: Independence, Power, and the Threat of Tyranny" (2001). Articles in Law Reviews & Other Academic Journals. 1397. https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/facsch_lawrev/1397 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Scholarship & Research at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles in Law Reviews & Other Academic Journals by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The American Prosecutor: Independence, Power, and the Threat of Tyranny AngelaJ. Davis' INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 395 I. DISCRETION, POWER, AND ABUSE ......................................................... 400 A. T-E INDF-ENDENT G E z I ETu aAD RESPO,\SE.................... -

Going Public: How the Government Assumed the Authority to Prosecute in the Southern United States

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects January 2016 Going Public: How The Government Assumed The Authority To Prosecute In The outheS rn United States Jason Twede Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/theses Recommended Citation Twede, Jason, "Going Public: How The Government Assumed The Authority To Prosecute In The outheS rn United States" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 1975. https://commons.und.edu/theses/1975 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GOING PUBLIC: HOW THE GOVERNMENT ASSUMED THE AUTHORITY TO PROSECUTE IN THE SOUTHERN UNITED STATES by Jason Allan Twede Bachelor of Arts, Weber State University, 2003 Juris Doctor, Thomas M. Cooley Law School, 2006 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of North Dakota in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Grand Forks, North Dakota May 2016 PERMISSION Title Going Public: How the Government Assumed the Authority to Prosecute in the Southern United States Department Criminal Justice Degree Doctor of Philosophy In presenting this dissertation in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a graduate degree from the University of North Dakota, I agree that the library of this University shall make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for extensive copying for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor who supervised my dissertation work or, in his absence, by the Chairperson of the department or the dean of the School of Graduate Studies. -

Criminal Prosecution Guide

CAREER DEVELOPMENT OFFICE JOB GUIDE CRIMINAL PROSECUTION Description Types of Employers Prosecutors work in all levels of government–local, state, Federal—U.S. Department of Justice: and federal. Prosecutors are responsible for representing the government in criminal cases, including Post-Graduate Jobs. The DOJ hires entry-level attorneys felonies and misdemeanors. At the state and local level, only through the Attorney General’s Honors Program. this work is typically done by District Attorneys’ Offices The application period is very short, typically the month or Solicitors’ Offices. Offices of State Attorneys General of August in the year prior to your graduation year. The may also have some responsibility for criminal matters of number of attorneys hired varies from year to year, and statewide significance or for criminal appellate or post- the positions are highly competitive. conviction matters. Federal criminal matters (e.g., financial crimes, drug enforcement, and organized Paid Summer Internships. The DOJ hires a number of crime) are typically handled by a U.S. Attorney’s Office students for paid summer positions through its Summer (USAO) either exclusively or in cooperation with the Law Intern Program. These positions are open to 1Ls Criminal Division of the Office of the U.S. Attorney and 2Ls, although most successful applicants intern General. during their 2L summer. Graduating law students who will enter a judicial clerkship or a full-time graduate program may intern following graduation. The application Qualifications period is very short, typically the month of August in the year prior to the summer you would be working. Many prosecutors’ offices prefer that entry-level attorneys have coursework, summer experience and/or Unpaid Internships. -

Charges to Be Declined: Legal Challenges and Policy Debates Surrounding Non-Prosecution Initiatives in Massachusetts

Boston College Law Review Volume 60 Issue 8 Article 7 12-2-2019 Charges to be Declined: Legal Challenges and Policy Debates Surrounding Non-Prosecution Initiatives in Massachusetts John E. Foster Boston College Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminal Procedure Commons, Law and Society Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons Recommended Citation John E. Foster, Charges to be Declined: Legal Challenges and Policy Debates Surrounding Non- Prosecution Initiatives in Massachusetts, 60 B.C.L. Rev. 2511 (2019), https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/ bclr/vol60/iss8/7 This Notes is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHARGES TO BE DECLINED: LEGAL CHALLENGES AND POLICY DEBATES SURROUNDING NON-PROSECUTION INITIATIVES IN MASSACHUSETTS Abstract: The election of “progressive prosecutors” introduces new objectives and tools into the traditional “tough on crime” playbook of local prosecution. Newly-elected District Attorney Rachael Rollins of Suffolk County, Massachu- setts has proposed one such tool: non-prosecution of certain criminal laws, chief- ly non-violent misdemeanors. This Note explores the likelihood of success of le- gal challenges to categorical non-prosecution, primarily whether non-prosecution unconstitutionally violates the separation of powers. This Note considers whether non-prosecution implicates the rights of victims and notions of justice as a public or private domain. -

The Prosecutor, the Term “Prosecutorial Miscon- Would Clearly Fall Within a Layperson’S Definition of Prose- Duct” Unfairly Stigmatizes That Prosecutor

The P ROSECUTOR Measuring Prosecutorial Actions An Analysis of Misconduct versus Error B Y S HAWN E. MINIHAN Rampant Prosecutorial Misconduct The New York Times, Jan. 4, 2014 The Untouchables: America’s Misbehaving Prosecutors, And The System That Protects Them The Huffington Post, Aug. 5, 2013 Misconduct by Prosecutors, Once Again The New York Times, Aug. 13, 2012 22 O CTOBER / NOVEMBER / DECEMBER / 2014 P ROSECUTORIAL MISCONDUCT has become nation- in cases where such a perception is entirely unwarranted… .”11 al news. To a layperson, the term “prosecutorial miscon- The danger inherent in the court’s overbroad use of the duct” expresses “intentional wrongdoing,” or a “deliberate term “prosecutorial misconduct” is twofold. First, in cases violation of a law or standard” by a prosecutor.1 where there is an innocent mistake or poor judgment on The newspaper articles cited at left describe acts that the part of the prosecutor, the term “prosecutorial miscon- would clearly fall within a layperson’s definition of prose- duct” unfairly stigmatizes that prosecutor. A layperson may cutorial misconduct. For example, the article “Rampant assume that the prosecutor intentionally committed a Prosecutorial Misconduct” discusses United States v. Olsen, wrongdoing or deliberately violated a law or ethical stan- where federal prosecutors withheld a report that revealed dard. sloppy work on the part of the government’s forensic sci- In those cases where the prosecutor has, in fact, commit- entists, resulting in wrongful convictions.2, 3 The article ted misconduct, the term “prosecutorial misconduct” may “The Untouchables: America’s Misbehaving Prosecutors, not impose a harsh enough degree of stigmatization. -

Private Prosecution: a Remedy for District Attorneys' Unwarranted Inaction

PRIVATE PROSECUTION: A REMEDY FOR DISTRICT ATTORNEYS' UNWARRANTED INACTION "[N]o stronger or more effectual guarantee can be provided for the due observance of the law of the land, by all persons under all circumstances, than is given by the power, conceded to everyone by the English system, of testing the legality of any conduct of which he disapproves, either on private or on public grounds, by a criminal prosecution." 1 STEPHEN, HISTORY OF THE CRIMINAL LAW 496 (1883). DISTRICT attorneys are required by statute to prosecute all matters of state concern.' But since mechanical enforcement of all criminal laws is undesirable and impractical,2 the district attorney is accorded extensive discretion in the selection of criminals and crimes to prosecute.3 The decision not to prosecute can be implemented by mere inaction,4 acceptance of a compromise plea,5 or 1. A typical statute provides: "The prosecuting attorney shall commence and pros- ecute all civil and criminal actions in [his county] . in which the county or state may be concerned . ." Mo. ANN. STAT. § 56.060 (Vernon 1949). A few codes specify the prosecutor's duties with more imperative language. For example, IowA CODE ANN. § 336.2 (1946) prescribes: "It shall be the duty of the county attorney to . diligently enforce ... all the laws of the state . .. ." 2. Society's interests are frequently better served by warning than by prosecuting; obsolete laws should not be enforced. See Snyder, The District Attorney's Hardest Task, 30 3. CRI. L. & C.rMINOLOGY 167, 168 (1939). In Commonwealth v. Dawson, 3 Pa. Dist. -

The Role of the Prosecutor: Serving the Interests of All the People

V INE.2PPR 03/14/01 10:33 AM THE ROLE OF THE PROSECUTOR: SERVING THE INTERESTS OF ALL THE PEOPLE Alan Vinegrad* The legal profession’s conception of public interest work has tradi- tionally focused on the work of pro bono or civil liberties-based organi- zations, such as the American Civil Liberties Union and its local chapters, a variety of legal defense funds, the Legal Aid Society, and other similar organizations. Certain law schools provide financial incentives and insti- tutional support designed to actively encourage their students to pursue job opportunities with these groups. Many students—the author in- cluded—can easily spend three years at a law school and not have any notion that public interest work also includes the job of being an Assistant District Attorney (local prosecutor), an Assistant Attorney General (state prosecutor), or an Assistant United States Attorney (federal prosecutor). Many others, aware of the general role of the prosecutor in our legal system, nevertheless have been steeped in publicity in recent years about the rather unique and increasingly politicized work of our most prominent prosecutors—the special prosecutors appointed under the now defunct Independent Counsel statute.1 From this publicity, one can easily draw incomplete, if not unfair, judgments about what it means to be a prose- cutor in our society. It did not occur to me until well into my legal career that my own notion of public interest work was under-inclusive in this one significant respect: it did not include the work of the tens of thousands of federal, state, and local prosecutors across the country who lead the legal fight against crime and protect our society and its citizens from those who seek to enrich themselves at society’s expense. -

Evaluating the Case for Greater Use of Private Prosecutions in England and Wales for Fraud Offences

Evaluating the Case for Greater Use of Private Prosecutions in England and Wales for Fraud Offences Chris Lewis, Graham Brooks, Mark Button, David Shepherd, Alison Wakefield Abstract This paper considers the challenges and opportunities that exist in England and Wales for the use of private prosecutions for Fraud. It considers the need for sanctions against fraudsters: looks at the prosecution landscape as it has evolved, especially during the 21st century: considers the legal basis for private prosecution and gives a brief history of its extent. The advantages and disadvantages associated with private prosecution are considered and recommendations made on the changes needed before there could be significant developments in the use of private prosecutions. Key Words: Fraud, Sanctions, Private prosecution, Fraudsters 1. Introduction This paper sets out to identify reforms to help fill the ‘sanctions gap’ in countering fraud. Special attention is paid to the role that private prosecutions could play in ‘punishing’ fraudsters. Results in this paper are taken from commissioned research (Button et al, 2012), involving a literature search from the UK and USA, 44 interviews in both public and private sectors and a questionnaire survey of around 400 members of the counter fraud community. 2. Fraud, Sanctions and Punishment Fraud is an extremely diverse problem encompassing a very wide range of acts (Doig, 2006). What unites them all is that they involve crimes that ‘… use deception as a principal modus operandi’ (Wells, 1997.) Fraud is a major problem to society (Levi et al, 2007), which the National Fraud Authority suggests cost the UK £73 billion during 2011 (National Fraud Authority, 2011). -

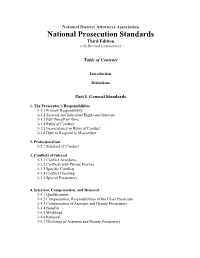

National Prosecution Standards, Third Edition Updated 2009

National District Attorneys Association National Prosecution Standards Third Edition with Revised Commentary Table of Contents Introduction Definitions Part I. General Standards 1. The Prosecutor’s Responsibilities 1-1.1 Primary Responsibility 1-1.2 Societal and Individual Rights and Interests 1-1.3 Full-Time/Part-Time 1-1.4 Rules of Conduct 1-1.5 Inconsistency in Rules of Conduct 1-1.6 Duty to Respond to Misconduct 2. Professionalism 1-2.1 Standard of Conduct 3. Conflicts of Interest 1-3.1 Conflict Avoidance 1-3.2 Conflicts with Private Practice 1-3.3 Specific Conflicts 1-3.4 Conflict Handling 1-3.5 Special Prosecutors 4. Selection, Compensation, and Removal 1-4.1 Qualifications 1-4.2 Compensation; Responsibilities of the Chief Prosecutor 1-4.3 Compensation of Assistant and Deputy Prosecutors 1-4.4 Benefits 1-4.5 Workload 1-4.6 Removal 1-4.7 Discharge of Assistant and Deputy Prosecutors 5. Staffing and Training 1-5.1 Transitional Cooperation 1-5.2 Assistant and Deputy Prosecutors 1-5.3 Orientation and Continuing Legal Education 1-5.4 Office Policies and Procedures 6. Prosecutorial Immunity 1-6.1 Scope of Immunity Part II. Relations 1. Relations with Local Organizations 2-1.1 Chief Prosecutor’s Involvement 2-1.2 Information Input 2-1.3 Organization Establishment 2-1.4 Community Prosecution 2-1.5 Enhancing Prosecution 2. Relations with State Criminal Justice Organizations 2-2.1 Need for State Association 2-2.2 Enhancing Prosecution 3. Relations with National Criminal Justice Organizations 2-3.1 Enhancing Prosecution 2-3.2 Prosecutorial Input 4.