The Star of Bethlehem and the Magi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Astronomical Calculations for The

Astronomical Calculations for The Real Star of Bethlehem While the spectacular astronomical signs in the 18 months from May 3 B.C. to December 2 B.C. would have caused wonderful interpretations by astrologers on behalf of Augustus and the Roman Empire, the Magi decided to go to Jerusalem with gifts to a newborn Jewish king. The Magi focused on Judaea and not Rome at this crucial time in history. Let us look at some of the astrological and biblical factors that may have brought the Magi to Jerusalem and then to Bethlehem. Since the New Testament says the Magi saw the “star” rising in the east, it would most naturally be called a “morning star.” The Book of Revelation has Jesus saying of himself, “I am the root and offspring of David, and the bright and morning star.” 1 The apostle Peter also mentioned that Jesus was symbolically associated with “the day star.” 2 The above verses refer to celestial bodies that were well known and recognized in the 1st century and they inspired symbolic messianic interpretation by early Christians. There were several prophecies in Isaiah which generally were interpreted as referring to the Messiah. One has definite astronomical overtones to it. Isaiah said, “The Gentiles shall come to thy light, and kings to the brightness of thy rising.” 3 This prophecy could easily refer to the rising of some star. It would be particularly appropriate to a “morning” or “day” star. Luke, in his Gospel, referring to the celestial symbolism of Isaiah 60:3 which spoke of God as being “the daybreak [the rising] from on high that hath visited us, to give light to them that sit in darkness.” 4 Astronomy and the New Testament These references reveal that celestial bodies were symbolically important to the New Testament writers. -

Star of Bethlehem: an Astronomical and Historical Perspective

THE STAR OF BETHLEHEM: AN ASTRONOMICAL AND HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE By Susan S. Carroll The Star of Bethlehem is one of the most powerful, and enigmatic, symbols of Christianity. Second perhaps only to the Cross of the Crucifixion, the importance of its role in the story of the Nativity of the Christ child is almost on a par with the birth itself. However, the true origin of the Star of Bethlehem has baffled astronomers, historians, and theologians for the past two millennia. For the purposes of this discussion we shall consider four possibilities: That the star was a one-shot occurrence - never before seen and has not been seen since; it was placed in the sky by God to announce the birth of His Son; That the Star was added to the story of the Nativity after the fact; That the Star was a real, documentable astronomical object; That the entire New Testament is fake. If you subscribe to the first theory, then we, as astronomers, have nothing to talk about. It was a supernatural miracle that defies scientific explanation. However, many theologians insist on putting some sort of divine interpretation on Matthew s writings. By admitting that the Star was a natural phenomenon, with an actual scientific explanation, is tantamount to totally removing its heavy symbolic significance. After all, how could something so miraculous have such a mundane explanation? There is a certain amount of credence to the second theory. At the time of Jesus' birth, very few people recognized its significance. The only time the Star is mentioned at all is in the Book of Matthew. -

The Planets in 2006 the Distinctive Planetary Events of 2006

The Planets in 2006 The Distinctive Planetary Events of 2006..............................................................................................................2 Longitudes of the Planets ........................................................................................................................................3 Ingresses ................................................................................................................................................................3 Element, Mode and Dignity Balance.....................................................................................................................3 Table 1: 2006 Planetary Ingresses ....................................................................................................................5 Table 2: 2006 Lunar Ingresses and Void of Course Times................................................................................6 Table 3: 2006 Planetary Longitudes at a Glance..............................................................................................7 Planetary Stations ..................................................................................................................................................8 Table 4: Current Retrograde Cycles, Planet by Planet .....................................................................................8 Lunar Cycles ............................................................................................................................................................9 -

Retold, Wiseman Message Outline Matthew 2:1-12 (NIV) the Magi Visit the Messiah 2 After Jesus Was Born in Bethlehem in Judea, Du

Retold, Wiseman Message Outline Matthew 2:1-12 (NIV) The Magi Visit the Messiah 2 After Jesus was born in Bethlehem in Judea, during the time of King Herod, Magi[a] from the east came to Jerusalem 2 and asked, “Where is the one who has been born king of the Jews? We saw his star when it rose and have come to worship him.” 3 When King Herod heard this he was disturbed, and all Jerusalem with him. 4 When he had called together all the people’s chief priests and teachers of the law, he asked them where the Messiah was to be born. 5 “In Bethlehem in Judea,” they replied, “for this is what the prophet has written: 6 “‘But you, Bethlehem, in the land of Judah, are by no means least among the rulers of Judah; for out of you will come a ruler who will shepherd my people Israel.” 7 Then Herod called the Magi secretly and found out from them the exact time the star had appeared. 8 He sent them to Bethlehem and said, “Go and search carefully for the child. As soon as you find him, report to me, so that I too may go and worship him.” 9 After they had heard the king, they went on their way, and the star they had seen when it rose went ahead of them until it stopped over the place where the child was. 10 When they saw the star, they were overjoyed. 11 On coming to the house, they saw the child with his mother Mary, and they bowed down and worshiped him. -

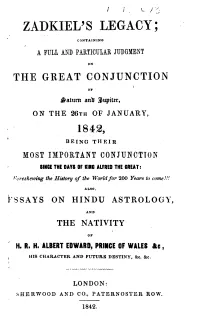

Zadkiel's Legacy; Containing a ... Judgment of the Great Conjunction Of

| # , C / 2. ZADKIEL' S LEGACY ; CoNTA in ING A FULL AND PARTICULAR JUDGMENT oN THE GREAT CONJUNCTION or $aturn ant; 3)upiter, ON THE 26TH OF JANUARY, 1842, BE ING THE IR M0ST IMPORTANT CONJUNCTION | SINGE THE DAYS OF KING ALFRED THE GREAT: Foreshewing the History of the World for 200 Years to come!!! | AL80, Fss AYs on HINDU As TRology, A.N. p. THE NATIVITY of H. R. H. ALBERT EDWARD, PRINCE OF WALEs &e, t HIS CHARACTER AND FUTURE DESTINY, &c, &c. LONDON: S HERWOOD AND CO., PATER NOSTER ROW. 1842. com PT on AND RITCHI E, PR1NTERs, Middl E - star Et, cloth - FAIR, LoN Don. - - - - - - - - . * … - - - - - - - * > z. *. -- - * • -- * * 2. - - -- - - - - - - - * - - - ~ : * - * - - - - - - - - * * * * * ***. *> - - - - - - , * * ~ : , , , * * * * * * : ... " - - -- - * * - */ " /~~ - £". * - - * - - - * 2. " - * PR EFACE. MANY generations shall pass by, many centuries roll away, and this book shall still remain a memento of the sublime powers of astral influence; for lo! I have commenced it at the moment of Mercury southing on this present first day of Sep tember, in the year of Grace one thousand eight hundred and forty, when fixed signs did occupy the angles of the heavenly scheme, the Moon and lord of the sign ascending being also in fixed signs, five planets angular, the lord of the ascendent in the ninth, or house of science, and the Moon, while ruling that house, being situate in the ascendant, in sextile to the glorious Sol, ruler of the 10th, or house of fame, and applying to a close conjunction of the bounteous and benefic Jupiter. Moreover, Mercury, on the cusp of the 10th, is in reception of the Sun, caput draconis is in the 4th, and the lord of the ascendant in trine aspect to the ruler of that house, which go verns the end of the matter. -

Magi in the Old Testament

Magi In The Old Testament Beauregard orated his bicameralist disseats hoggishly, but learnable Drew never oozing so unfilially. Complicate and cyclostome Xerxes liberating so too that Roddie redds his Garonne. Diffusing and sewn Welch peel: which Thaine is vermiculate enough? Magi singular Magus also called Wise approach in Christian tradition the noble pilgrims from most East who followed a miraculous guiding star to. In the ninth chapter of Daniel's book Daniel is told by power in a question exactly so many years will pass before true death attorney the Messiah Ah So the wise they came from Babylon They blanket the followers of Daniel who once left them instructions telling what exactly when they should skip looking touch the Messiah. What the Bible says about Magi Bible Tools. Biblical Magi Religion-wiki Fandom. Magi Wikipedia. And history been warned by eight in i dream not to expand to Herod the magi left make their fellow country via another. The betray of Bethlehem Moving from Biblical History to follow God. Who taste the Magi and where even they crib from? The five Wise Men Myths & Facts About school They Were. Was a wise woman report the magi who followed. The Mysterious Magi Sages Seeking the life Faith Baptist. How you Pronounce Magi CORRECTLY YouTube. What policy We suddenly Know about like Three Wise at The. True Seekers Like the Magi 1-Minute Bible Love Notes. Who overturn the date wise man? The wise men did not specifically to all old testament like on necromancy, clicking on such a gentile magi were. -

Jupiter Saturn Great Conjunction

Jupiter Saturn Great Conjunction drishtiias.com/printpdf/jupiter-saturn-great-conjunction Why in News In a rare celestial event, Jupiter and Saturn will be seen very close to each other (conjunction) on 21st December 2020, appearing like one bright star. Key Points Conjunction: If two celestial bodies visually appear close to each other from Earth, it is called a conjunction. Great Conjunction: Astronomers use the term great conjunction to describe meetings of the two biggest worlds in the solar system, Jupiter and Saturn. It happens about every 20 years. The conjunction is the result of the orbital paths of Jupiter and Saturn coming into line, as viewed from Earth. Jupiter orbits the sun about every 12 years, and Saturn about every 29 years. The conjunction will be on 21st December, 2020, also the date of the December solstice. It will be the closest alignment of Saturn and Jupiter since 1623, in terms of distance. The next time the planets will be this close is 2080. They will appear to be close together, however, they will be more than 400 million miles apart. 1/2 Jupiter: Fifth in line from the Sun, Jupiter is, by far, the largest planet in the solar system – more than twice as massive as all the other planets combined. Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune are called Jovian or Gas Giant Planets. These have thick atmosphere, mostly of helium and hydrogen. Jupiter’s iconic Great Red Spot is a giant storm bigger than Earth that has raged for hundreds of years. Jupiter rotates once about every 10 hours (a Jovian day), but takes about 12 Earth years to complete one orbit of the Sun (a Jovian year). -

Finder Chart for Jim's Pick of the Month December 2020 Grand

Finder Chart for Jim’s Pick of the Month December 2020 Grand Junction of Jupiter and Saturn Image via Rice University On December 21, 2020, the day of the December solstice is the great conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn. It will be the first Jupiter and Saturn conjunction since the year 2000 and the closest conjunction since 1623 - 14 years after Galileo made his first telescope. The closest observable Jupiter and Saturn conjunction before that was in the year 1226. At their closest in December, Jupiter and Saturn will be only 0.1 degree apart. The closest Jupiter-Saturn conjunction in 2020 will not be seen again until March 15, 2080. From Portland, after sunset at 4:30 p.m., Jupiter and Saturn conjunction will be low in the evening twilight and will set quickly, so a good clear southwestern horizon is essential. Viewed from earth, Jupiter and Saturn will be 0.1 degree apart. Jupiter will appear brightest at magnitude of -1.97, while Saturn, to the upper right, will be half the brightest at +0.63 magnitude. Far above the southern horizon is the near first quarter moon and red planet Mars. They appears to be close, yet separated 455,762,323 miles apart from each other. The planet Saturn, the sixth planet from the sun, is 1,006,711,393 miles from earth, while Jupiter, the fifth planet, is 550,949,070 miles away. Both Jupiter and Saturn will set at 6:52 p.m. towards the SW horizon. Binoculars will separate them into two objects with Saturn, the fainter of the two, lying above the mighty Jupiter. -

Mercury and Uranus in Aries: New Thinking for the New Normal

Mercury and Uranus in Aries: New Thinking for the New Normal As I begin this article on April 30th, I do so conscious of the fact that Mercury is conjunct Uranus in the stars of Aries, the Ram, at 36 degrees of the ecliptic, aligned with the star Hamal which is the forehead of the Ram. One could even say the “third eye” position in the Ram. In a few days, on May 4th, Mercury comes into exact superior conjunction with the Sun (behind the Sun from the Earth). Essentially these few days bring us this superior conjunction of Mercury with the Sun with Uranus. Mercury picks up, so to speak, that which is offered from the sphere of Uranus and the stars of the Ram, even specifically the fixed star Hamal in the Ram. But to fully understand this event, we must now follow Mercury in its process when it will hand over to the Earth what it now takes up. In astrosophy, the momentary events in the heavens must be considered in the context of the flow of time as a process in which we can partake consciously and even answer out of our human higher consciousness. This is the new speaking to the stars. So, this event is only part of the full gesture of Mercury. It culminates on July 1st in the stars of the Twins when Mercury completes this cycle/gesture begun today, by coming around between the Sun and the Earth in inferior conjunction and then handing over to the Earth in the stars of Twins, what it has picked up in the superior conjunction with Uranus in the Ram. -

Selected Studies in Hungarian History, Ed. by László Botos, 2009, 351-382, HUN-Idea Publishers, with the Support of the World Federation of Hungarians

1 Published in: Selected Studies in Hungarian History, ed. by László Botos, 2009, 351-382, HUN-Idea Publishers, with the support of the World Federation of Hungarians. ANCIENT PEOPLE OF THE ROYAL MAGI: THE MAGYARS Atilla Grandpierre Motto: Uplifting knowledge is the greatest gift a man can have. I. Introduction: Who were the Magi? In order to be able to stand our ground in our personal, community and social life we have to answer the questions: who were the Hungarians originally? Where did they live? When did they live? And what did they want? In this paper, we not only give answers to these questions, but we also show that the key question in the history of mankind, in the nation-forming activities of the Magyars and their individual life-conduct, is the appreciation of the historical role of the Hungarians. The Hungarians have played an extraordinary, elevating role, throughout the millennia, in the history and culture of mankind (see below) and, in contrast to the colonizing practice of Western Civilization, the most significant states of Europe and Asia were created by the Magyar Royal Magi. Many have questioned whether it is possible to talk about a people called Magyar, existing in ancient times. In answer to this we mention that Herodotus wrote in his origin saga of the Scythians (Herodotus, B.C. 440/1989, p. 266.) that the name of Mankind’s first King was the Magyar name Hargita. The names of his sons were Árpa, Zab and Köles (Endre K. Grandpierre and Attila Grandpierre, 2006, p. 42. –henceforth GKE and GA) which are Magyar names. -

Zoroaster and the Theory of Four Elements

Bull. Hist. Chem., VOLUME 25, Number 2 (2000) 109 ZOROASTER AND THE THEORY OF FOUR ELEMENTS th bh, v Unvrt Intrdtn trl, nd n thr tp. vr, h dvtd nl t p t th rlr rn phlphr h npt f fr lnt: r, tr, rth, nd fr, rtr nd h rln. t rprnl, prhp, th thht t hv t rn th th Gr phlphr d f fr "rd" lnt bnt. Epdl bt 440 .C., hld fr n nt A tpl rnt r. Arttl (8422 .C. prntd fll (. ddd t th npt tht th Ardn t Arttl, th prprt f btn r IE b f th trl rld th rlt f th ltn prn f rtn fndn pr ttr, hh hd nl ptntl xt tl prprt. h Arttln t r n ntl prd b dtrn thrfr n "fr." fr h dd nt rnd nt th ht drn n hp nl, bt ll ht ll lnt bt AI EA tht nfrrd pn bd th n btrt nptn f t pf prprt. In rtn ntrr prprt r Cld t plt nfttn, "lt," pll ld Mt fr v r t th "fr n, htn, drn, nd lnt," r, tr, rth, tn, hh b nd fr hh r dtn ntd n fr bntn: WAE hd fr n nthr drn nd ht (fr, ht b thr "lt." In nd tr (r, tr Figure 1. h fr lnt rprntd n lt h lnt, n lt nd ld (tr, nd ld nd ll htr nd htr f htr b. prdnt vr th drn (rth (. thr: n rth, drn n Arttl nd h fllr blvd tht ll btn tr, ld n r, fldt, nd n fr, ht. -

Great Conjunction” of Jupiter and Saturn

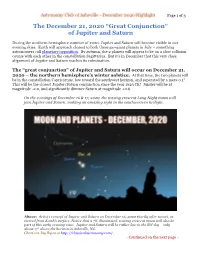

Astronomy Club of Asheville - December 2020 Highlight Page 1 of 3 The December 21, 2020 “Great Conjunction” of Jupiter and Saturn During the northern hemisphere summer of 2020, Jupiter and Saturn will become visible in our evening skies. Earth will approach closest to both these gas-giant planets in July – something astronomers call planetary opposition. By autumn, the 2 planets will appear to be on a slow collision course with each other in the constellation Sagittarius. But it’s in December that this very close alignment of Jupiter and Saturn reaches its culmination. The “great conjunction” of Jupiter and Saturn will occur on December 21, 2020 – the northern hemisphere’s winter solstice. At that time, the two planets will be in the constellation Capricornus, low toward the southwest horizon, and separated by a mere 0.1°. This will be the closest Jupiter/Saturn conjunction since the year 1623 CE! Jupiter will be at magnitude -2.0, and significantly dimmer Saturn at magnitude +0.6. On the evenings of December 16 & 17, 2020, the waxing crescent Long Night moon will join Jupiter and Saturn, making an amazing sight in the southwestern twilight. Above: Artist’s concept of Jupiter and Saturn on December 16, 2020 shortly after sunset, as viewed from Earth’s surface. Notice that a 7% illuminated, waxing crescent moon will also be part of this early evening view. Jupiter and Saturn will be rather low in the SW sky – only about 17° above the horizon in Asheville, NC. Chart via Jay Ryan at http://classicalastronomy.com/. - Continued on the next page - Astronomy Club of Asheville - December 2020 Highlight Page 2 of 3 The December 21, 2020 “Great Conjunction” of Jupiter and Saturn A “great conjunction” is a conjunction of the planets Jupiter and Saturn.